UKIYO-E (JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS)

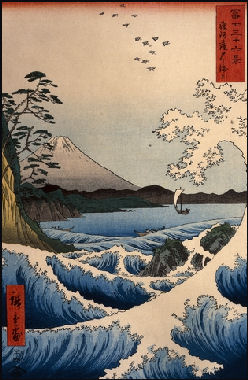

Woman by Utamaro Woodblock printing in Japan is known as “ukiyo-e”, literally "pictures of the floating world." One of the most popular forms of Japanese art, it was created for the contemporary masses and depicts images of urban life and natural scenes that ordinary people could relate to and enjoy. The "floating world" is a Buddhist metaphor that refers to the changing world of fleeting pleasures, which were often found both in seasonal changes of nature and the entertainment districts of Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto.

“Ukiyo-e” is derived from “uki,” a Buddhist-derived term denoting the state of mind conveyed by the German word “weltschmerz” (“disenchantment with the actual,” or “world weariness”). During the Edo period the kanji (Chinese character) for “uki” was replaced, playfully, by the homophone kanji for “float” and “ukiyo” took on antithetical meaning — the worldly ‘sea of trouble” became ‘sea of tranquility,” in which impermanence was celebrated not lamented. [Source: Mark Austin, Daily Yomiuri]

Ukiyo-e is flatter and simpler than Western art. In its time the floating images of leisure and luxury were avidly consumed by a rising population of middle-class hedonists who bought them for their sheer visual pleasure.

Among the Westerners who collected ukiyo-e were Vincent Van Gogh, the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright and the painter Claud Monet. Wright once said, "The Japanese print is one of the most amazing products of the world and I think no nation has anything to compare with it."

Van Gogh copied “Plum Garden in Kameido” and “Great Bridge, Sudden Shower at Atakae” from Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”. The background of Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Pere Tanguay” shows several ukiyo-e’s that the artist collected. Monet was an enthusiastic collector of uikyo-e. His collection, which included numerous works by Utamaro and Hokusai, is on display today ay his famous house in Giverny. Paul Gaugin also collected ukiyo-e.

Ukiyo-e prints are famous for their exquisite calligraphic lines, bold composition, dramatic colors and flat, unshaded subjects. Some images are serene and dignified and look at home in a museum while others are full of drama and violence and look as if they belong in a comic book. Usually only a few hundred or a few thousand prints were made. On average a printer could make about 200 prints a day.

Ukiyo-e was inspired by everyday Edo pleasures and urban leisure pursuits like drinking, whoring and attending Kabuki theaters as well as visiting scenic spots around Japan. Ukiyo-e prints depicted tea ceremonies, theaters, sumo wrestlers, women bathing in wooden tubs, picnics under cherry trees, excursions to pastoral lakes, prostitutes, sexual acts, actors, and make-believe characters like warriors, mythical animals and monsters. One major source of inspiration was Yoshiwara, an entertainment district in Edo (Tokyo), where daimyos and members of the Imperial court mingled, attended sumo bouts and kabuki plays and enjoyed the company of prostitutes.

Ken Johnson wrote in the New York Times: “Today’s comic book artists and graphic novelists owe a huge debt of gratitude to Hokusai, Hiroshige and other Japanese artists who, with wonderful formal and technical ingenuity, illustrated tales of martial conflict, high seas adventure, travel and erotica, and sold them cheap in vast quantities to the pre-20th-century equivalents of manga and anime fans.” [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, April 15, 2010]

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Guide to Ukiyo-e Sites on the Internet ukiyo-e.se/guide.html ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; Library of Congress Collection loc.gov/exhibits/ukiyo-e ; Minneapolis Institute of Arts artsmia.org ; Viewing Japanese Prints viewingjapaneseprints ; Ukiyo-e Pictures of te Floating World ukiyo-e.se ; Jim Breen’s Ukiyo-e Gallery csse.monash.edu.au/~jwb/ukiyoe ; Art.com www.art.com ; Artelino Japanese Prints artelino.com ; Gallery Sakura gallery-sakura.com ; Asian Collector’s Internet Auction woodblockprint.com ; Ukiyo-e from the Sweetbriar Collection artgallery.sbc.edu/ukiyoe ; Ohmi Gallery ohmigallery.com ; Book: “Japanese Woodblock Printing” by Rebecca Salter (A&C Black, 2001). Gallery in Tokyo Ebisu-do Gallery, Inagaki Building, 4F, 1-9 Kandajimbocho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo . Tel. (03)-3219-7651www.ebisu-do.com

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ; Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EDO PERIOD ART Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UKIYO-E, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE EDO PERIOD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPAN, THE WEST AND THE EDO PERIOD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; LIFE AND CULTURE IN THE EDO PERIOD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

History of Woodblock Printing in Japan

17th century print of a woman Woodblock printing originated in China but was greatly improved by the Japanese through the skill of Japanese craftsmen and introductions of washi paper, which tolerates repeated printing and absorbs color without collapsing; the development of the kento method or printing, which ensured that layers of were color correctly applied and aligned; and the invention of the “baren”, a circular pad mad from compressed laminated paper that was used in manual printing to apply the flat colors so pleasing to fans if ukiyo-e.

The Tokugawa shogunate came to power in Japan in 1603 and succeeded in bringing peace and stability to Japan, both economically and politically. As the merchants in Edo (later Tokyo) and Kyoto became more and more wealthy under its regime, they began to take control of cultural activities. Paintings from the period called Kan’ei (1624-1644) depicted people from every class of society crowding the entertainment district beside Kyoto’s Kamogawa river. Similar districts existed in Osaka and Edo, where the uninhibited lifestyle of the “ukiyo “(floating world) transpired, that ultimately came to be glorified by the art genre known as “ukiyo-e”. These “ukiyo-e”, which often featured brothel districts and “kabuki “theater, gained popularity throughout the country. First produced in the form of paintings, by the early eighteenth century “ukiyo-e “were most commonly produced as woodblock prints. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The first ukiyo-e in the 17th century were simple monochrome black prints. Later "red prints" appeared. They were followed by yellow and green prints, and eventually full color prints known as “nishikie”, were developed in the middle of the 18th century. Ukiyo-e was reportedly founded by a printer named Iwa Matabie and popularized, beginning in 1681, by Hishikawa Moronobu, an artist who lived among ordinary people and found inspiration among them. He rose to fame by producing images of famous erotic tales, scenes from the entertainment district in Yoshiwara and portraits of beautiful women. As an art form ukiyo-e drew on and synthesized Chinese painting. Yamato-e (classical Japanese Painting) and byobu-e (screen painting).

Techniques of Japanese woodblock printing originated in Kyoto and Osaka but are most closely associated with Edo (Tokyo). Early prints from the Edo Period between 1660 and 1720 featured only black and white printing. Color printing had not been invented and colors were applied by hand.

“Among the first types of printed “ukiyo-e “were sex manuals called “shunga “(pornographic pictures). These books or albums showed very explicit love scenes. Many early ukiyo-e were how-to sex manuals for brides and courtesans and erotic prints pertaining to the red-light entertainment districts in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. There were also picture books with commentary that contained portraits of the leading prostitutes of the time, typically involved in some mundane activity such as washing their hair. It is their poses or the draping of their “kimono “that provides the main focus of these scenes.

Ukiyo-e Develops in Edo (Tokyo) and Becomes Popular in the West

“By late in the century, the core activity of “ukiyo-e “had moved from the Kyoto-Osaka area to Edo, where portrayals of “kabuki “actors became standard subject matter. The public also showed great fondness for “ukiyo-e “featuring beautiful women. By the late eighteenth century, “ukiyo-e “had entered its golden age. Feminine beauty, and especially the tall, graceful women who appeared in the work of Torii Kiyonaga, was a dominant theme in the 1780s.

“After 1790 came a rapid succession of new styles, introduced by artists whose names are so well known today: Kitagawa Utamaro, Toshusai Sharaku, Katsushika Hokusai, Ando Hiroshige, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, to single out but a few.

Some of the greatest works emerged in the 1840s, when censorship was imposed in Japan on artists and entertainers and laws were passed prohibiting conspicuous displays of wealth, irreverence or negativity toward authority and anything sexually provocative, from portraits of famous courtesans to pornography. With the United States and other nations pressing for open trade with Japan, it was a time of political anxiety and economic flux, which prompted conservative efforts to control perceived excesses of popular culture.

For some Westerners, including the greatest artists in Europe in the late nineteenth century, “ukiyo-e “was more than merely an exotic art form. Artists such as Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh borrowed its stylistic composition, perspectives, and use of color. Frequent use of themes from nature, which had been rare in Western art, widened painters’ selection of themes. Émile Gallé, a French artist and glass designer, used Hokusai’s sketches of fish in the decoration of his vases. With the advent of the Meiji period (1868--1912) and its policy of Westernization, “ukiyo-e”, which had always been closely linked to the culture from which it drew its themes and vitality, began to die out quickly.

Many of the of the best works of ukiyo-e are found now outside of Japan in places like British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Many of these were snatched up in the years following the end of Edo Period — as Japan rushed towards modernization — when ukiyo-e was seen as passe and disposable, and Western collectors acquired huge masses of work for a song. Almost half of the 25,000 prints, books and paintings at the Victoria &Albert Museum — regarded as one of the largest and finest collections of ukiyo-e n the world — was obtained in a single purchase from a London dealer in 1886.

Japanese Woodblock Print Workshops

Making woodblock prints was a collective effort involving drawers, carvers, publishers and printers. Many of the craftsmen worked in workshop run for generations by their family.

The workshops in turn were supported by a large variety of skilled craftsmen who produced the printmaking equipment, the dyes and pigments, the cherrywood boards used by the cravers. The cherrywood boards came from trees cut from mountainsides, seasoned for years and planed to a metal-like sheen so the wood would not chip when it was being worked by the carvers and no trace of the grains remained. The carving tools were often made by samurai sword makers.

Ukiyo-e were used in and posters were made at a rate of thousands per week with over a hundred artists making them. Sometime 15,000 prints were made from the same blocks. The first prints were the best. They contained details and painterly touches that were often lost during the subsequent runs.

Ukiyo-e prints are still made today but the art is dying out as traditional materials become scarce and the younger generation shows little interests in carrying on the craft. Many Ukiyo-e artists now making a living making wrapping paper and woodblock prints of contemporary art.

Making Ukiyo-e Prints

The process of making a woodblock print started with an artist making a designs with brush-and-ink lines on transparent paper, indicating which colors were needed. Beyond that the artist had little involvement in the finished product. Separate woodblocks were carved for each color. Sometimes it took a carver months to complete all the blocks necessary to make a single print.

The carvers used the original drawings as templates, pasting the designs face down with rice glue on planed blocks of cherry wood and carved the lines of the design in relief. The carvers often cut right through the original drawing of the artist, which explains why the lines were so flowing and also explains why so few original drawings remain. The carvers were highly skilled and were masters at rendering what the artist had intended. It was said they were so talented that they could capture the difference between living and dead hair.

The prints were made by applying colored ink to a block with a brush, pressing down a sheet of paper and rubbing it with a special bamboo skin patch. The skill of a printer was measured by his ability to achieve accurate alignments. Printers covered the sheets with a gluey liquid that prevented blurring and kept the ink from running. When a work was finished it was marked (usually) with the artists signature, a publisher's mark, a censor' seal and occasionally a date seal. Unfortunately the names of the carvers and printers were not recorded.

The colors were achieved by mixing different pigments and applying more or less pressure. Color graduations were made by wiping ink from the blocks before printing or putting a little water in the block. The prints were often dusted with mica powders for a glittering effect. In some cases, an embossed effect was given to the design by pressing fabric patterns into the paper. The best paper were sheets measuring 48.5 centimeters by 33.5 centimeters made in Fukui Prefecture.

The intense colors of many works comes from synthetic, Western pigments like Prussian Blue imported from Holland. Human figures are drawn in traditional “hikime kagihana” — an abbreviated but expressive style in which eyes are depicted as lines, and noses by hooks

Edo-Tokyo Museum curator Naomi Wagatsuma told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “techniques became much more developed by the end of the Edo period, when pigments from overseas enabled artists to incorporate vivid colors that left a stronger impression than the previous vegetables pigments...After the middle period of paintings, it became the trend to print on larger canvases, split into three or five panels. The motifs, too, shifted, from focusing on one person such as an actor or beautiful woman, to genre paintings.”

Marketing Ukiyo-e Prints

actor by Sharaku The effect of ukiyo-e prints on art in Japan was similar to the effect of the printing press on literature in Europe. Although they were treasured in the West, woodblock prints were regarded as mass-produced disposable items in Japan. They were sold cheaply and they were intended for everyone to enjoy. They were often looked at and thrown away like newspapers or used as wrapping paper for ceramics. Ukiyo-e images also found their way into small illustrated books known as kyoka and onto a objects such as uchiwa- and sensu-shaped fans. Hokusai, Utamaro and Sharaku all had the works placed n these fans.

Ukiyo-e was a business that had a profound effect on literature and publishing as well as art. The ukiyo-e industry was highly competitive. To get an edge on competitors, printers hired poets and writers to crate text and encouraged artists to experiment and used new colors and forms. Printers and carvers were often hired on their ability to capture the subtleties of the artists.

Published controlled the making and distribution of printed images, often touting new innovations such as metallic chios and glossy lacquer to sell more images. Among the most famous publishers was Tsutaya Juzaburo, who worked with Utamoro, Hokusai and ukiyo-e legends. He marketed everything from portraits of kabuki actors to pornography. Landscapes sold particularly well.

“Surimone” are woodblock prints that were privately commissioned and given as gifts rather than mass produced and sold like ukiyo-e. They came in variety of sizes and shapes, but were often the size of postcards. Many were commissioned by artist and often they were made a team that included the artist, the poet, calligrapher and printer. They often contained mother of pearl, lacquer or some expensive pigment

Many surimone have a literary connection, Commission were often earned through connections made at poetry parties, where artists, writers, actors and other creative people gathered and composed ribald poems known as “mad verse.” One verse found on an image of a courtesan created around 1800 by Hokusai and the poet Santo Kyoden goes: “Sometimes I turn into a could/like smoke from tobacco I have lit,/ other times I turn into rain/ which makes a client linger a bit.”

First printings are highly valued not only because the quality of the printing is exceptionally good but also, according to Edo-Tokyo Museum curator Naomi Wagatsuma, because “printers and publishers faithfully followed the advise of the artists on things such as coloring.”

Shunga, Sex and Art

Japanese “shunga” ("spring pictures") are sexually-explicit woodblock prints that were popular in the Edo period (1603-1868). Some featured couples in a variety of sexual positions. Others features humorous depictions of men with enormous penises or couples with enlarged genitalia. Some are quite crude. Others are exquisitely done and are regarded as works of art. works Even Japanese famous artists such as Utamaro and Hurunobu made them.

Shunga held a large share of the ukiyo-e market. There are number of theories why they were so popular. Some have suggested it was because they were pornography and nothing more. Some have said they served as trousseaus for brides to prepare for their wedding night. Other have suggested that were an aid for masturbation. Masturbation is not equated with sin and weakness like it os the West. And because of husbands were often separated from the wives due to Edo period laws, masturbation was preferred to infidelity.

Works that look mundane often had a sexual meaning. A swing lantern, a peony and a boat pole all had sexual connotations.

“Nawashibari”, erotic rope binding, was developed in 17th century Japan by samurai who used similar methods to torture criminals.

Van Gogh, Foreigners, and Japanese Woodblock Prints

The Impressionists and other artists in France and Europe were entranced by the beauty and color of Japanese woodblock prints that began arriving from Japan after it opened up to the outside world in 1854. European artists were also excited by the asymmetrical composition styles of Japanese art, and the use of few strokes to suggest an object rather than rendering a detailed miniature version of it.

The art critic Samuel Bing wrote in “Le Japon Artistque” in 1888: "The Japanese are poets moved and inspired by the great spectacle of nature and attentive observers of the familiar mysteries of a world of exceeding minuteness. They learn geometry from the spider's web, take decorative motifs from the tracks of a bird across the snow and receive inspiration of curved designs from the ripples of the wind on the water...They believe that there is nothing in the world of creation that is not suited of the high ideals of art."

Vincent van Gogh was an enthusiastic collector of Japanese art and had a collection of over 100 ukiyo-e prints. He once referred to Japan as "the land of the blue tones and gay colors" and was fascinated with the way that Japanese prints portrayed deep space with flat shapes. Van Gogh wrote: “I admire the Japanese for the enormous clarity that pervades their work.”

Ukiyo-e found its way into several van Gogh paintings. Van ogh interpreted two Hiroshige landscapes. His “Irises” was inspired by Hokusai’s print of the same subject. “Geishas in a Landscape” by Torakiyo Sato, one his favorite ukiyo-es, is in background of “Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear”, a work created three weeks after van Gogh sliced off part of his ear.

The influence of Japanese woodblock prints is also evident in the works of Toulouse La Trec, Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas. The poet Baudelaire was among the earliest collectors.

Ukiyo-e and the Development of Western Modern Art

Hiroshige Fuji Souren Melikian wrote in the International Herald Tribune: “The role played by the discovery of Ukiyo-e...in the formation of modern art cannot be overemphasized. The copies in oil of a Hiroshige (1797-1858) print by Van Gogh, the influence that the Japanese woodcuts had on his color scheme — including the combination of ultramarine blue and acid yellow that he owes to Hiroshige — are well known.” [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, September 24, 2010]

“The bold layouts of Hiroshige inspired the revolutionary compositional rules devised in the 1890s by Nabi painters. Most important, it was probably as a result of the direct influence of Japanese woodcuts that color in Western painting ceased to depict what the eye sees. It became a marker as in Japanese prints and was applied in juxtaposed areas.”

“No mountain, not even in Japan, ever looked like Hokusai’s Mount Fuji in the print titled “Cool Breeze on a Clear Morning” the second in the famous series of “Thirty Six Views of Mount Fuji” printed in the 1830s. A deep blue band hems the outline of the mountain, which is pure white inside to signify snow. On the lower reaches colored a pale blue, tiny, almost abstract, dark green cones stand for pine trees. This kind of Spartan composition paved the way for equally minimalist pictures in later European movements.”

Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Woodblock Prints

Non-Japanese collectors snapped up prints which were sometimes so little regarded in Japan they were used as wrapping paper.The famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was the premier dealer of Japanese prints in the early 1890s. He filled his own home with Asian art he kept his own personal collection of woodblock prints in a vault near his drafting table and often gazed at his favorite prints for inspiration. In his autobiography, Lloyd said, "If Japanese prints were to be deducted from my education, I don't know what direction I might have taken."

Wright bought and sold thousands of Japanese prints between the 1890s and his death in 1959 and made a fortune from his dealings. At one point he made considerably more from trading prints than he did from his architecture projects. He often bought cheaply in Tokyo and then sold at "notoriously high prices" in the United States.

By the time Wright started collecting seriously in the 1920s, demand for Japanese art was very high and unscrupulous Japanese art dealers were producing contemporary knock-offs of the original Edo

Collecting Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e is more affordable than many people think. Prints by Hiroshige can be purchased for as little as $100. A Katsushika print starts at $200. The most expensive prints are early Edo period works. Some collectors recommend buying works from ukiyo-e specialty stores because they know the true of value works and are less likely to pawn off cheap prints at a high price.

The woodblocks are used a number of times to create a single picture, and over time the quality of the prints can suffer. Ones used for advertisements and posters sometimes produced thousands of copies a day. This why the original, the 100th copy, the 500th copy or even 700th copy of the same picture have such different values. How the prints have been stored also has bearing on their value. Faded colors, holes, chips, blemishes or stains, or paper stuck on the back will reduce the value of prints.

Ukiyo-e prices are deternined with a point system, with points deducted for flaws. Under this system a high quality print image may sell for tens of thousands of dollars while a lower quality print of the same image might sell for few hundred dollars.

Ukiyo-e Sale and Decline in Interest in Japanese Art

In September 2010,Souren Melikian wrote in the International Herald Tribune: “Two historic sales took place last week in Paris and New York. The dramatic contrast between the lackluster outcome of the French auction that dealt with Japanese color prints and the hugely successful American auction devoted to Chinese art in part mirrors the changing power balance between the two great cultures of the Far East. The four-day sale in Paris conducted by the Pierre Bergé group would have aroused immense interest in an earlier age. At the core of it was the collection built up from the 1950s through the 1970s by Huguette Berès, a legendary figure in collecting and dealing circles famous for her sharp eye. Multiplied tenfold by her daughter Anisabelle Berès, the holdings to which the Berès name was attached represented the most important offerings in the field seen at auction since the 1970s. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, September 24, 2010]

“With the Berès name and some great rarities, plus scores of delightful and affordable prints, the sale would have caused a sensation in the days when collecting Japanese prints was a widespread pursuit. But collectors have almost vanished. The Japanese who had looked down on Ukiyo-e as a kind of street art until the 1950s and then rediscovered the despised woodcuts under Western influence, became ardent buyers with the new converts’ determination. The 1990 slump put paid to Japanese art collecting in most fields.

“A more complex process of decline has hit Western collecting of Japanese woodcuts. The scarcity of top quality impressions gradually discouraged leading collectors. Collecting passion withers away if it is not regularly fed. No less important, the ability to perceive nuances and the visual culture required to tell a fine impression from a lesser one have been eroded over the years.

“There was little enthusiasm at the Berès sale, which realized only 2.86 million euros, or $3.83 million. A few of the great prints commanded reasonable prices, if lower than 20 years ago. Hokusai’s “Cool Breeze on a Clear Morning” went for 68,200 euros. Among the rarities of the sale were a number of preparatory sketches by the artists who designed the prints. An album of 40 sketches dashed off by Hiroshige in spontaneous strokes also brought 68,200 euros, prompting a representative of the National Museums Agency to stand up, saying that the agency was substituting itself to the highest bidder, as French law allows.”

But some marvelous woodcuts excited little competition. Hokusai’s “Poppies in the Breeze,” printed around 1830-1832, made it only to 17,360 euros. A striking album of sketches by Korin (1658-1716), so modern in appearance that they seem to anticipate some Western works on the eve of World War I, was eminently accessible at 8,680 euros. So was Hiroshige’s bold “View of a Clump of Trees at Suijin and in the Village of Sekiya Outside Masaki” at 9,920 euros. Several of the most important works, notably actor portraits by Sharaku, failed to find takers. Scores of lovely woodcuts with estimates ranging between a few hundred and 5,000 euros were also spurned. Not quite matching the mint condition demanded by museums, they retained their beauty virtually intact. The constituency that these enjoyed until the early 1980s no longer exists.

Japanese art is on the retreat on every front. Sotheby’s and Christie’s London no longer maintain Japanese departments. Eskenazi of London had a Japanese department that was closed when the expert running it, Luigi Bandini, died and the entire stock was sold off at Christie’s on Nov. 17, 1989.

Image Sources: British Museum, Library of Congress, National Museum in Tokyo

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2012