RAPE OF NANKING

One of the most horrible events of the Japanese occupation of China was the Rape of Nanking. Unspeakable atrocities were committed throughout the Yangtze Delta, which includes Nanking as well as Shanghai. No one knows how many Chinese were butchered. The extent of the atrocities did not come to light until after the end of World War II. The Japanese have estimated that 100,000 troops and unarmed Chinese civilians were killed. The Chinese figure is 300,000. The reason for the disparity of views on the number of victims is that many killings took place outside the city limits, and that deaths in battle and deaths by execution are not always distinguished.

In November 1937 , Chinese forces abandoned the imperial capital of Nanking—before the Japanese even arrived. From December 1937 to March 1938, Japanese terrorized the people of Nanjing. POWs and men suspected of being Chinese soldiers in civilian clothes were marched by Japanese soldiers to execution sites and gunned down en masse. Women were gang-raped in front of their families; streets were filled with rotting corpses; Japanese soldiers pulled carts full of loot; children were casually murdered. The world was shocked by Japan's brutal aggression. Even swastika-wearing Nazis set up safety zones for Chinese. In many Japanese cities, by contrast, people held lantern parades to celebrate the capture of Nanking. [Source: Ian Buruma, New York Review of Books, October 13, 2011]

The Chinese also showed a dark---and cowardly --- side. Chinese military officers fought their way out of the city, by trampling and pushing the lower ranks out of the way. Some Chinese who were trying to flee the city were shot in the back by other Chinese. Foreign heros included John Rabe, who managed to use his Nazi credentials to save quite a number of Chinese, and Minnie Vautrin (the “Anne Frank of China”), who tried to save women from being dragged away from their families.

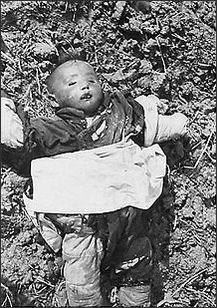

Child killed in Nanking massacre

Book: "Rape of Nanking The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II" by Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang was an international best seller. Uncompromising and quite graphic in its description of the horrors that took place after the Japanese arrived in Nanking, it relies on the testimonies of survivors, eyewitness accounts of Western observers, and Japanese soldiers. The book contains numerous eyewitness accounts of rapes, beheadings, murders and other crimes at the hands of Japanese troops. Information on the massacre remains quite scarce. Tillman Durdin of the New York Times, Archibald Steel of the Chicago Daily and Leslie Smith of Reuters were in Nanking at the time of the incident. For an excellent documentary film of the role of the foreigners, see Nanking (2007), directed by Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman.

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; BURMA AND LEDO ROADS factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BRUTALITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Rape of Nanking The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II" by Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang Amazon.com; “Battle of Shanghai: The Prequel to the Rape of Nanking” by Luke Diep-Nguyen Amazon.com ; “Japan's Infamous Unit 731: Firsthand Accounts of Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” (Tuttle Classics) by Hal Gold and Yuma Totani Amazon.com; “Unit 731 Testimony: Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” by Hal Gold Amazon.com; “Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II” by Laurence Rees Amazon.com; “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) Amazon.com; Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com; “The Imperial Japanese Army Volume 1: Japan, the Annexed Territories and Manchuria” by Roderick S. Grigor Amazon.com; “Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism” by Louise Young Amazon.com;

Atrocities During the Rape of Nanking

Chinese farmer shot dead by Japanese

The slaughter lasted for six weeks. One relief agency buried 100,000 people; the Red Crescent buried 43,000. In just five days, the Japanese disposed of 150,000 bodies by throwing them in the Yangtze. [Source: Denis and Peggy Warner, International Herald Tribune]

According to Women Under Seige: “Japanese troops forced families to commit incest, according to Chang. Fathers were forced to rape their daughters; sons, their mothers. Those who refused were killed instantly. Some of the most despicable forms of torture leveled at the civilian population, according to Chang, included being buried waist-deep in the earth and then attacked by German shepherd dogs; being buried alive; and being doused in gasoline and set on fire. [Source:Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org]

“A document from February 3, 1938, among the papers of The Nanking Massacre Project of Yale Divinity School Library, lists a series of abuses perpetuated against Chinese soldiers and civilians by Japanese troops: acid poured over the dead bodies of executed soldiers, as well as those who were still alive; a young farmer virtually decapitated; young children shot; and Chinese civilians injured or killed during the Japanese troops’ search for women to rape.

Tillman Durdin, a New York Times correspondent, witnessing several days of atrocities in Naking and then left for the city for Shanghai in order to send a dispatch home. He wrote: “Just before boarding the ship for Shanghai, the writer watched the execution of 200 men. The killings took just ten minutes. … The conduct of the Japanese army as a whole in Nanking was a blot on the reputation of their country. Their victory was marred by barbaric cruelties, by the whole sale execution of prisoners, by the looting of the city, rapes, killing of civilians and by general vandalism.”

Examples of Atrocities of Rape of Nanking

On December 13, 1937, Japanese soldiers entered Nanking, then the capital of China. During the assault, Japanese soldiers were involved in mass rapes, point-blank executions,and public beheadings. They buired people alive; killed people at random; raped women, girls and boys; bayoneted people tied to stakes; used Chinese peasants as human minesweepers; and looted and set fire to shops, temples, houses and churches.

On December 13, 1937, Japanese soldiers entered Nanking, then the capital of China. During the assault, Japanese soldiers were involved in mass rapes, point-blank executions,and public beheadings. They buired people alive; killed people at random; raped women, girls and boys; bayoneted people tied to stakes; used Chinese peasants as human minesweepers; and looted and set fire to shops, temples, houses and churches.

Lewis S.C Smythe was professor at Nanjing University during the war and secretary of the International Committee for the Nanjing Safety Zone. He worked as a member of the International Red Cross Committee of Nanjing. In a letter to his wife on December 23, 1937 he wrote: “The Japanese soldiers took 200 people from the refugee camp...and shot them to death, some of them may be soldiers, but it was said that more than half of them were ordinary people. We hope the wrath of Japanese was done and there will be no more shooting...Today another man came back, his face was severely burnt, which may result in blindness. He said 140 of them were binded together, poured with gasoline and fired! It was horrible!”

Japanese soldiers raped thousands of girls and women, many of whom were dragged from their homes. By the end of December, 20,000 cases of rape had been reported. One girl was raped 37 times. Another had her four-month-old son smothered by the soldier who raped her. Some Japanese soldiers raped pregnant women, killed them, cut the fetuses out of their bodies and then had their picture taken with the fetuses. Some young Chinese women disguised themselves as elderly women to escape being raped.

One former Japanese soldier, who confessed to sexually assaulting a Chinese woman with a wooden sword, said "I kept beating her until her skin broke and started to bleed, but she didn't answer my questions." A soldiers that ate the flesh of a young Chinese boy said, "It was the only time, and not so much meat."

Photographs taken by Japanese show Imperial army soldiers holding up severed heads; placing, their feet on dead women and babies; rape victims begging for mercy; and soldiers standing beside dead people hung from ropes as if they were prize fish. Some Japanese soldiers competed among themselves to see who could kill the most Chinese. Two sub-lieutenants, battling to be the first to reach 100, reportedly beheaded 167 people in a single day (See Below).

John Rabe’s Accounts of Atrocities at Nanking

Last breaths of man ready to be buried alive

John Rabe was a German businessman who worked for the Siemens Company and had resided in China since 1908. He was living in Nanking at the time of the Japanese invasion and was instrumental in establishing a “Safety Zone” within the to city to protect civilians and unarmed soldiers. Describing the “Safety Zone” on December 13, 1937, John Rabe wrote in his diary: We “are quickly convinced of the miserable conditions in these hospitals, whose doctors and nurses simply ran away when the shelling got too heavy, leaving the sick behind with nobody to care for them....The dead and wounded lie side by side in the driveway leading up to the Foreign Ministry. The garden, like the rest of Chung Shan Lu, is strewn with pieces of cast-off military equipment. At the entrance is a wheelbarrrow containing a formless mass, ostensibly a corpse, but the feet show signs of life...It is not until we tour the city that we learn the extent of the destruction. We come across corpses every 100 to 200 yards. The bodies of civilians that I examined had bullet holes in their backs. These people had presumably been fleeing and were shot from behind. [Source: Eyewitness to History eyewitnesstohistory.com; This eyewitness account appears in: Rabe, John, The Good Man of Nanking, Erwin Wickert (ed.) (1998); Chang, Iris, The Rape of Nanking (1998). ^]

“The Japanese march through the city in groups of ten to twenty soldiers and loot the shops. If I had not seen it with my own eyes I would not have believed it. They smash open windows and doors and take whatever they like. Allegedly because they're short of rations. I watched with my own eyes as they looted the cafe of our German baker Herr Kiessling. Hempel's hotel was broken into as well, as was almost every shop on Chung Shang and Taiping Road. Some Japanese soldiers dragged their booty away in crates, others requisitioned rickshas to transport their stolen goods to safety. ^

“We run across a group of 200 Chinese workers whom Japanese soldiers have picked up off the streets of the Safety Zone, and after having been tied up, are now being driven out of the city. All protests are in vain. Of the perhaps one thousand disarmed soldiers that we had quartered at the Ministry of Justice, between 400 and 500 were driven from it with their hands tied. We assume they were shot since we later heard several salvos of machine-gun fire. These events have left us frozen with horror. ^

“Mr. Han says that three young girls of about 14 or 15 have been dragged from a house in our neighborhood. Doctor Bates reports that even in the Safety Zone refugees in various houses have been robbed of their few paltry possessions. At various times troops of Japanese soldiers enter my private residence as well, but when I arrive and hold my swastika armband under their noses, they leave. There's no love for the American flag. A car belonging to Mr. Sone, one of our committee members, had its American flag ripped off and was then stolen.” ^

Looting and Mass Execution in Nanking

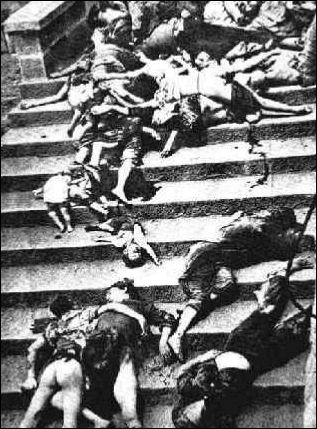

Blood pond filled with more than 300 dead Chinese

John Rabe wrote in his diary: December 16: “All the shelling and bombing we have thus far experienced are nothing in comparison to the terror that we are going through now: There is not a single shop outside our Zone that has not been looted, and now pillaging, rape, murder, and mayhem are occurring inside the Zone as well. There is not a vacant house, whether with or without a foreign flag, that has not been broken into and looted...No Chinese even dares set foot outside his house! When the gates to my garden are opened to let my car leave the ground… women and children on the street outside kneel and bang their heads against the ground, pleading to be allowed to camp on my garden grounds. You simply cannot conceive of the misery. [Source: Eyewitness to History eyewitnesstohistory.com^]

"The road to Hsiakwan is nothing but a field of corpses...I've just heard that hundreds more disarmed Chinese soldiers have been led out of our Zone to be shot, including 50 of our police who are to be executed for letting soldiers in. The road to Hsiakwan is nothing but a field of corpses strewn with the remains of military equipment. The Communications Ministry was torched by the Chinese, the Y Chang Men Gate has been shelled. There are piles of corpses outside the gate. The Japanese aren't lifting a hand to clear them away, and the Red Swastika Society associated with us has been forbidden to do so.^

“It may be that the disarmed Chinese will be forced to do the job before .. they're killed. We Europeans are all paralyzed with horror. There are executions everywhere, some are being carried out with machine guns outside the barracks of the War Ministry...As I write this, the fists of Japanese soldiers are hammering at the back gate to the garden. Since my boys don't open up, heads appear along the top of the wall. When I suddenly show up with my flashlight, they beat a hasty retreat. We open the main gate and walk after them a little distance until they vanish in the dark narrow streets, where assorted bodies have been lying in the gutter for three days now. Makes you shudder in revulsion. All the women and children, their eyes big with terror, are sitting on the grass in the garden, pressed closely together, in part to keep warm, in part to give each other courage. Their one hope is that I, the 'foreign devil' will drive these evil spirits away."

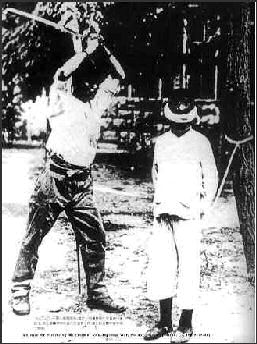

First to Kill 100 Men with a Sword

Reports say that on the way to Nanking two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, held a killing contest to determine who could kill 100 men the fastest, using only a sword. The “contest was widely reported in Japanese newspapers, with some keeping tally and reporting scores as if it were a sporting event. [Source: Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org]

Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and its sister newspaper the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun covered the “contest.” Both officers supposedly surpassed their goal during the heat of battle, making it impossible to determine which officer had actually won the contest. Therefore, (according to the journalists Asami Kazuo and Suzuki Jiro, writing in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shimbun of December 13), they decided to begin another contest, with the aim being 150 kills. The Nichi Nichi headline of the story of December 13 read "'Incredible Record' [in the Contest to] Behead 100 People—Mukai 106 – 105 Noda—Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings". [Source: Wikipedia +]

Many soldiers and historians have said the events were exaggerated and sensationalized by the Japanese press. Noda admitted as such in a speech he gave in his hometown: “Actually, I didn't kill more than four or five people in hand-to hand combat... We'd face an enemy trench that we'd captured, and when we called out, 'Ni, Lai-Lai!' (You, come on!), the Chinese soldiers were so stupid, they'd rush toward us all at once. Then we'd line them up and cut them down, from one end of the line to the other. I was praised for having killed a hundred people, but actually, almost all of them were killed in this way. The two of us did have a contest, but afterward, I was often asked whether it was a big deal, and I said it was no big deal.” [Source: Honda, Katsuichi (1999), Main text from Nankin e no Michi (The Road to Nanjing), 1987]

Japanese veteran Shintaro Uno wrote an autobiographical account that he consecutively beheaded nine prisoners with his sword, comparing his experiences with those of officers involved in the killing contest. In regard to this, Japanese historian Katsuichi Honda, noted: “Whatever you say, it's silly to argue about whether it happened this way or that way when the situation is clear. There were hundreds and thousands of [soldiers like Mukai and Noda], including me, during those fifty years of war between Japan and China. At any rate, it was nothing more than a commonplace occurrence during the so-called Chinese Disturbance.”

Eyewitness Accounts of Rapes in Nanking

A Chinese eyewitness in Chang’s book describes the body of an 11-year-old girl who had been raped continuously for two days: “…The blood-stained, swollen and ruptured area between the girl’s legs created a disgusting scene difficult for anyone to look at directly.”[Source: Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org]

Old Chinese woman raped and killed by Japanese at Taierzhuang

Women were often killed after being raped. Their bodies were mutilated with bayonets, sticks, bottles, and other objects that were shoved into their vaginas. One eyewitness, Li Ke-hen, quoted in James Yin and Shi Young’s Rape of Nanking: an Undeniable History in Photographs, reported: "There are so many bodies on the street, victims of group rape and murder. They were all stripped naked, their breasts cut off, leaving a terrible dark brown hole; some of them were bayoneted in the abdomen, with their intestines spilling out alongside them; some had a roll of paper or a piece of wood stuffed in their vaginas.”

Nazi party member John Rabe wrote in a report to Hitler, according to author Iris Chang: “They would continue by raping the women and girls and killing anything and anyone that offered any resistance, attempted to run away from them or simply happened to be in the wrong place, at the wrong time. There were girls under the age of 8, and women over the age of 70 who were raped and then, in the most brutal way possible, knocked down and beat up. We found corpses of women on beer glasses and others who had been lanced with bamboo shoots. I saw the victims with my own eyes—I talked to some of them right before their deaths and had their bodies brought to the morgue at the Kulo hospital so that I could be personally convinced that all of these reports had touched on the truth.”

American missionary Minnie Vautrin, president of Ginling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences, was also instrumental in saving the lives of thousands of Chinese civilians—particularly women and girls—during the siege. On December 16, 1937, she noted in her diary: “There probably is no crime that has not been committed in this city today. Thirty girls were taken from the language school last night, and today I have heard scores of heart-breaking stories of girls who were taken from their homes last night ... one of the girls was but 12 years old.”

Chu-Yeh Chang, a survivor of the Nanking massacre, experienced and witnessed the violence sweeping through Nanking firsthand: “On New Year’s Eve of 1937 … five Japanese soldiers charged into our house, forced my father and me out, and then raped my mother, my 80-year-old great-grandmother, and my 11-year-old-sister.”

Account of a Nanking Rape Victim

Liu Xiuying, a 78-year-old survivor told a court in Tokyo in 1996: "The Japanese troops entered the city on Dec. 13, 1937. We were about 100 young women sheltering in the cellars of a building. On the afternoon of the 18th a group of soldiers came and some of us were taken by force."

"We knew what they were doing to women," she said. "They were dragging them into a neighboring building where they were often raped. The following morning some soldiers returned and one of them seized me by the arms. I was 19 and I was seven months pregnant. I resisted with all my force and I bit him on the arm. He screamed and his colleagues came immediately."

The soldiers lept on her and stabbed her 37 times in the face and stomach. She was left for dead in a pool of blood. The next day she lost her child but miraculously survived. She was taken to a Protestant church where she was taken care of by an American. "I can't forget, and I can't forgive," she said. "From that day on and for years to come, I had nightmares. I was so disfigured that I never left the house. I couldn't work. Even today my face sometimes hurts."

John Rabe, a German in Nanking at the time of the massacre wrote in his diary, “An American once said, 'The Safety Zone has become a brothel for the Japanese.' This statement is largely in accordance with the facts. Yesterday night around 1,000 girls and women were raped, in the Jinling Women's College alone, more than 100 girls were raped. These days all one hears about is rape. If brothers or husbands come out to interfere, they're shot by the Japanese. All about me is the cruel violence and brutality of the Japanese army thugs.]

Machine Gun Squads in Nanking

Machine-gun squads worked for hours non-stop executing people. Tillman Durdin of the New York Times wrote that he saw the execution of 200 men in 10 minutes. After Durdin's account's were printed, the Japanese imposed a news blackout and restricted vehicles from coming to and going from Nanking.

A correspondent for a Tokyo newspaper later reported that he saw a continuous procession of Chinese taken to an execution area near the Yangtze River. He saw piles of burned corpses covering an entire wharf and 50 to 100 Chinese workers dragging the bodies and throwing them in the river. After their work was done, the Chinese workers were lined up and executed.

One Chinese man later told AP he was lined up on December 14, 1937 with 300 people mowed down by machines gun. He said he awoke under a pile of bodies. "Slowly, slowly, I made my way out. My coat was completely soaked with blood. I thought I was a ghost.” When he went to the river to wash he found the water red with blood from hundreds of dead bodies.

One account from classified Chinese documents goes: “In the last ten days of December, the campaign to clear the streets began...Japanese soldiers, in groups of three to five, went from door to door wielding long swords, loudly screaming out orders, and insisting the doors be opened...those who had been hiding inside...could not help but poke their heads out their doors to look around and see what happened outside. The catastrophe befell them. The moment they opened their doors...the Japanese opened fire. On this day alone, the dead and wounded numbered in the thousands.” [Source: "Japanese Imperialism and the Massacre of Nanjing" by Gao Xingzu, Wu Shimin]

Why Were the Japanese So Brutal in Nanking

Motivation remains a central question. Why did the Japanese army massacre the city? Or, on an individual level, why would a Japanese soldier turn so blood-thirsty? Why did the people not fight back? Or on the same an individual level, why would an ordinary citizen not fight back? Why didn't the citizens flee? Did no one anticipate the Japanese army's atrocities? Ian Buruma wrote, "This cannot be explained by a particular culture or history. After all, in previous wars, such as the Russo-Japanese War in 1904---1905, Japanese soldiers were renowned for their discipline. Unfortunately, men from all nations are capable of extreme viciousness, once the animal inside is unleashed."

Motivation remains a central question. Why did the Japanese army massacre the city? Or, on an individual level, why would a Japanese soldier turn so blood-thirsty? Why did the people not fight back? Or on the same an individual level, why would an ordinary citizen not fight back? Why didn't the citizens flee? Did no one anticipate the Japanese army's atrocities? Ian Buruma wrote, "This cannot be explained by a particular culture or history. After all, in previous wars, such as the Russo-Japanese War in 1904---1905, Japanese soldiers were renowned for their discipline. Unfortunately, men from all nations are capable of extreme viciousness, once the animal inside is unleashed."

No one knows exactly why the Japanese soldiers behaved so brutally. In the Japan-Russia War of 1905, the Japanese went of their way to treat prisoners of war with mercy. Explanation for their behavior in Nanking include the samurai code of honor and a desire by the Japanese to terrorize the Chinese into surrendering.

In the Japanese-made film "Japanese Devils" (2001) by Minori Matsui, 14 former Japanese soldiers who served in China were asked why atrocities were committed. They said that horrible things were done to civilians not out of stress or fanaticism but rather because they regarded the Chinese as less than human and potential spies; they wanted to be a member of the group; and they were worried that if they didn't do terrible things their manhood would be questioned.

Committing atrocities was condoned and even encouraged. One man in the film said that he and his comrades wiped out an entire village simply for the thrill of it. Another said he burned a mother and her newborn baby alive and stuck around to hear their screams.

The soldiers claimed their brutal training---in which they were beaten by their superiors and subjected to cruel hazing by their peers with the object of crushing their "arrogant" individuality---turned them from village farm boys into heartless soldiers who were able to kill without feeling.

Buruma wrote, “Cultural expression, whether in art, religion, manners, or ceremony, is often a way of channeling and taming energy that is potentially dangerous. Shinto, literally the Way of the Gods, was officially promoted in wartime Japan as the main manifestation of Japanese spiritual culture. What had existed for centuries as a nature cult, praying to the gods for good crops, fertility, and good weather, was turned into a militant form of chauvinism. One of the vignettes in City of Life and Death shows the Japanese soldiers dancing, banging drums, and chanting in a Shinto ceremony to celebrate the fall of Nanking. Too subtle to blame Shinto, even militant Shinto, for Japanese brutality in 1937, Lu illustrates instead the tenuous borderline between ritualized violence and the real thing. The scene also shows the danger of putting young men, locked in the cocoon of their own culture, in an alien environment, where they can easily come to feel that rules of civilized behavior no longer need to apply.

Rape of Nanking from the Japanese Side

Azuma Shiro, one of the first Japanese war veterans to discuss his participation in the Nanking Massacre, said in the 1998 documentary called In the Name of the Emperor: “It would be all right if we only raped them—I shouldn’t say all right. But we always stabbed and killed them. Because dead bodies don’t talk.” [Source: Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org]

One soldier, Takokoro Kozo, recalled to Chang: “Women suffered most. … No matter how young or old, they could not escape the fate of being raped. We sent out coal trucks from Hsiakwan to the city streets and villages to seize a lot of women. And then each of them was allocated to 15-20 soldiers for sexual intercourse and abuse.”

“Author and journalist George Hicks, in The Comfort Women: Japan’s Brutal Regime of Enforced Prostitution in the Second World War, claimed that Japanese soldiers often wore amulets made from the pubic hair or personal possessions of victims in order to protect themselves in battle. The prevailing military superstition was that having sex before any major military incursion would work as a kind of protective charm. Hicks also wrote that the actions of the Imperial Japanese Army were possible because of the prevailing notion at that time that masculine needs took precedent and that it was a woman’s duty to serve men. As Japanese tradition has it, the woman should walk two steps behind the man; as Confucianist philosophy has it, a woman must obey first her father, then her husband, and finally her son, Hicks said.

The Nanking War Crimes Tribunal, which was led by Chinese authorities in 1946, tried four Imperial Japanese officers accused of committing war crimes, including the two officers involved in the killing contest of 100 people. General Iwane Matsui was held primarily responsible for failing to stop the mass violence and rape that befell Nanking upon Japanese occupation, despite the fact that the general, suffering from tuberculosis, had arrived late to Nanking. While rape charges were part of the indictment against Matsui, victims were not called to give their testimonies, according to the UN report on sexualized violence in conflict. Matsui was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging.

Account of Nanking in Chinese History Book

According to "Modern and Contemporary Chinese History, Book One": “Wherever Japanese went, they committed all manners of crimes: arson, homicide rape and looting. In December, 1937, Japanese armies occupied Nanjing ad massacred the city’s peaceful residents, the ultimate act of human cruelty. Within six weeks more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers in Nanjing were murdered. The means of massacre were extremely brutal. Some victims were bayoneted some were were buried alive; some were cremated alive.”

”The Japanese military commander, Tani Hisao, and his troops entered Nanjing and killed whoever they saw. At the time, numerous refugees, unarmed Chinese citizens and wounded were crowded into the city. They were killed by Japanese soldiers manically shooting with machine guns, rifles and pistols. Crowds of old people, women and children were felled.”

”The Japanese armies also smashed their way into civilian houses and randomly killed residents living peacefully in Nanjing. They hauled a young man into the street, stripped his clothes, poured aqua fortis [nitric acid solution] on his body and forced him walk until his death; they tied captured soldiers on pillars, stabled them with awls till they became bleeding bodies, and finally thrust bayonets into their throats; they also gang raped pregnant women, cut open their wombs and took out the embryos to play with on the top of their bayonets.”

Account of Nanking in Japanese History Book

According to "Japanese History B": “In August, hostilities broke out in Shanghai and the flames of war spread south...Japan continuously committed a large army [to the area], and occupied the Nationalist government capital in Nanjing by the end of the year...Because the Nationalist government retreated from Nanjing to Hankou and the further inland to Chonqing and persistently continued to resist, the Sino-Japanese war became a quagmire-like drawn-out war.”

A foot note from the book reads: “In addition to repeated looting and violence within and outside Nanjing at the time of its fall, the Imperial Japanese Army murdered a large number of Chinese noncombatants (including women and children) and prisoners (Nanjing incident).”

In 1995, a right-wing political party in Japan took out a full page ad in the New York Times claiming the Rape of Nanking never took place. In Japanese textbooks from the 1980s the only reference to the "Rape of Nanking" was a footnote that called it the "Nanking Incident." See Textbooks, World War II.

City of Life and Death: Film About the Nanking Massacre

“City of Life and Death” (2009) is a Chinese-made film by Lu Chuan about the invasion of Nanking in 1937 that has been both praised and condemned for portraying the Japanese in a somewhat sympathetic light. The film depicts the Nanking massacre through the eyes of a Japanese soldier who is shocked and terrified by the atrocities committed by his compatriots and ultimately kills himself after letting a Chinese prisoner of war escape. Even though the film attracted a large audience and was approved by the Communist Party, Lu was accused by some as being a traitor.

“City of Life and Death” won the top award at the San Sebastian film festival in Spain Lu won an award at the Tokyo Film festival for his film “Kekexili: Mountain Patrol” about men trying to protect Tibetan antelope from poachers. For “ City of Life and Death” he won the Best Director award at the fourth Asian Film Awards, held during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. While the film continues to garner attention following its successful theatrical run in China and international premiere at the Toronto Film Festival last year, it has yet to be shown theatrically in the US, following an aborted spring release with National Geographic.

Shelly Kraicer wrote in Cinema-scope: “It is a full-out war epic, massively budgeted and vast in ambition. Huge sets of devastated Nanjing were built, and thousands of extras mobilized to illustrate the battle scenes that open the film. Lu films his striking set pieces in a beautifully modulated black and white, where cinematography, art direction, staging, music, and sound design all conspire to create massive, intentionally overwhelming images of violence, horror, and devastation.”

Ian Buruma wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Lu Chuan’s film is highly unusual in several ways. Apart from the dedication and a few scenes of Chinese screaming “Long live China!” before being machine-gunned into the Yangtse River, there is nothing especially patriotic or polemical about the movie. On the contrary, it is almost too easy on the Japanese. The real story of Nanking was far worse than what is shown in this film. A particularly refreshing departure from the usual depiction of squat, buck-teeth-baring, thick-necked, bloodthirsty Japanese villains is the lack of any stereotyping. On the whole, the Japanese soldiers are shown as ordinary young men, rather more handsome on average than they might have been in real life, thrown into extraordinary circumstances. And the main Japanese character, Sergeant Kadokawa (Hideo Nakaizumi), is a bewildered, naive figure whose conscience is so shocked by what he sees that he ends up shooting his brains out. [Source: Ian Buruma, New York Review of Books, October 13, 2011]

However, the development of individual characters is not the movie’s strong point. Lu is better at conveying group behavior. Shot in black and white, the film is made up of a series of sometimes surprisingly poetic vignettes of man’s inhumanity to man. The reenactment of the atrocities, even though in a somewhat muted form, is not what makes this film original, however. More interesting is the way Lu, who served for two years in the People’s Liberation Army, dramatizes the behavior of young men who can switch from moments of humanity, even tenderness, to savagery in a matter of seconds. He makes nonsense of the cultural theories about the Japanese being uniquely and naturally brutal because of ancient warrior codes or whatnot. Instead, he shows how terrifying ordinary young men can be when they exercise their power over people who have none. Anyone who has encountered large groups of soccer supporters, whether they be British, Dutch, German, or Argentinian, recognizes the phenomenon. One minute, they will be singing along, happily enough, and the next minute, sparked by anything at all, they erupt into mob violence, and once that happens brutality can escalate fast. The sight of first blood invites more. It is as if the helplessness of the victims only provokes greater aggression.

In City of Life and Death, the Japanese soldiers, all but two of whom are acted by Chinese, look like Japanese men of their generation: innocently horsing around, singing popular songs, clowning in country dances. And then, those same boys (most are little more than that) turn into savage beasts, pumped up with predatory violence.

Lu takes other risks in this film, apart from his refusal to depict Japanese simply as villains. In most patriotic Chinese films, especially ones made in the People’s Republic of China, a traitor is a traitor, and a hero a hero, and there can be no possible confusion between the two. However, the main Chinese character in the film, Mr. Tang (Fan Wei), is an example precisely of such a confusion. He is John Rabe’s assistant, speaks some broken Japanese, and does what he can to protect people in the safety zone. A good man, in other words. But he is not just responsible for helping the refugees; Tang is also a husband, and father of a small daughter. Tang thinks he can protect his family by making a deal with the Japanese, informing them that there are Chinese soldiers hiding among civilians. In exchange, the Japanese agree to protect his family from any harm. A traitor? A family man? Both? As it happens, the Japanese still murder Tang’s little daughter, and Tang ends up sacrificing his own life for that of another Chinese. A hero, after all? Such ambiguities are rare in Chinese films.

Image Source: Nanjing History Wiz, Wiki Commons, History in Pictures Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021