EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II

Hirohito and Tojo

The Japanese involvement in World War II has it roots in the country's rapid industrialization and modernization after the 1866. In less than 50 years, Japan went from a feudal society to one capable of building iron-clad battleships. It has been argued that the main issue that World War II tried to settle was how to make a place for newly industrialized nations of Germany and Japan in the new world order.As part of the 1928, Kellogg-Briand Pact, the United States, France, Britain, Germany, Italy and Japan agreed to renounce war. Even so the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island was preparing contingency plans for war with Japan as early as 1897.

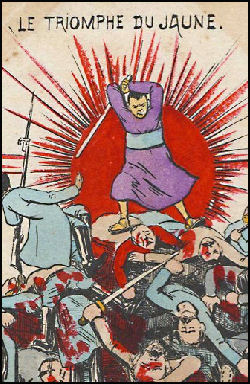

The Japan wanted respect from the West. When the Western powers decided not to endorse a statement of racial equality at the Versailles Conference in 1919, the Japanese took it as a direct snub, which in fact it was. After that it seemed Japan like Japan wanted to be taken seriously as a world power.

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; RAPE OF NANKING factsanddetails.com; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; BURMA AND LEDO ROADS factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BRUTALITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 by Geoffrey Jukes Amazon.com; “Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear: Russia's War with Japan” by Richard Connaughton Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “Imperialism in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries —With a Focus on the Case of Japan in Korea” by John B. Duncan Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century” by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert P Bix Amazon.com; “Imperialism in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries —With a Focus on the Case of Japan in Korea” by John B. Duncan Amazon.com; “The Culture of the Quake: The Great Kanto Earthquake and Taisho Japan (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2015) Amazon.com; “Party Rivalry and Political Change in Taisho Japan” (Harvard East Asian Series, 35) by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert P Bix Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com

Sino-Japanese War

Japan was the dominant power of Asia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Meiji reforms and the rise in Japanese military strength helped allow Japan to abolish foreign treaty rights and bypass China to become the leader in Asia.

In the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War, Japan easily defeated China in a war that would decide who would control the Korean peninsula. Weakened by decades of foreign occupation, China was forced to sign a series of unequal treaties with Japan that gave Formosa (present-day Taiwan), the Pescadores Islands, Port Arthur and the Liaotung peninsula in southern Manchuria to Japan. The independence of the Korean peninsula was also recognized.

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) is known as the Jiawu War in China. It lasted only year. The decisive moment was the surprising defeat of the Chinese navy at the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894. The Treaty of Shimonoseki forced China to cede Taiwan and the Penghu Islands, pay a large indemnity, allow Japanese industry into four treaty ports and recognize Japan's hegemony over Korea. [Source: Zhang Lei Global Times, May 17 2011]

Russo-Japanese War

Views of Japan in the West In 1904-1905, Japan defeated Russia in Russo-Japanese War, showing that the world that Japan was major world power and that Czarist Russia was on its last legs. The Japanese attacked the Russians in Korea and Manchuria and won the war by unexpectedly crushing Russia's Baltic fleet at the Battle Tsushima. The Japanese lost 60,000 men and the Russians, 30,000. One general described the war as a “mountain of corpses.”

At the beginning of the war Russia was considered one of the world's super powers and the Japanese army was still regarded as second rate. Most people thought that Russia would easily win. Some saw the conflict as the first modern war. It at least was the first modern naval war in which ironclad navies with long-range guns faced one another. But it was also a war of old-style military maneuvers such as a Cossack charges, the scaling of ancient city walls and elaborate courtesies between commanders.

The origin of the war dated back to the end of the war against China in 1885 when Russia, Germany and France asked Japan to leave Port Arthur (Dalian) and the Liaotung Peninsula in northeast China. Japan gave into the demands. In 1886, Russia seized the territory for itself and then occupied Manchuria. In 1875, Russia and Japan agreed on how to divide the islands east of Russia. Russia got Sakhalin Island and the Japanese got the Kuril Islands. Disagreement arose on "spheres of influence" in which Russia wanted Manchuria and Japan wanted Korea. Poor diplomacy was based on starting the war. Japan prepared for war by strengthening its navy and forming an alliance with Britain, the world' leading trade and naval power. In 1904, Japan broke diplomatic relations with Russia.

Russia surrendered and signed a peace treaty on September 5, 1905 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in the United States. The Japanese asked U.S. president Teddy Roosevelt to mediate the settlement. Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to get the two nations to sign the treaty. This was the first Nobel prize to go to an American.

The peace agreement was largely seen as a compromise and in the eyes of the Japanese a capitalization. Even though Japan’s victory at sea was decisive its army could not prevail over the Russian army on land. Even after the war was over the armies of the two nations faced down each other in Manchuria and it often seemed there was a risk that a new conflict would erupt any time.

see Japan, History

Legacy of the Wars with China and Russia

The Russo-Japanese War brought Japan to the attention of the world as a power to be reckoned with and the uncontested leader of Asia. The defeat of Russia was seen as a slap in the face for all of Europe. It was the first defeat of a major European power since the Mongols. But not everyone saw it such grim terms. Many, especially the British, cheered Japan’s success. Some conservatives in Britain applauded “brave little Japan.”

The victories over Russia and China, established Japan as the first great, modern, non-Western power in Asia. The Japanese leaders felt it was their duty to avenge the humiliation inflicted on Asia during the colonial period after the Opium War in 1842.

By defeating Russia, Japan knocked out its only naval rival in the eastern Pacific. Japan also took over Russia's concessions in China and annexed half of Sakhalin island, which later was used as a stepping stone to Manchuria and Korea. Japan’s failure to seize significant territory in Russia and China was considered a setback not because it was a threat to Japan's military and economic interests but because it was considered a sign of weakness that ran contrary to the "stud duck in the pond" image that Japan was trying to project.

Rise of Militarism in Japan

As the Meiji Period ended, Japan seemed to be on the road to establishing a normal parliamentary government. But instead there was a loss of confidence in political parties, opening the way for right-wing nationalists and militarists to take control of the government.

The rise of Japanese militarism has been blamed on hardships caused by the worldwide depression, reaction to anti-Japanese sentiments in China, numerous scandals in Japan, flaws in the Meiji constitution that paved the way for the military's rise to power and other factors.

At the end of 19th century, as Japanese went to war with China, a nationalist party was created and other political parties were forced to disband. The Diet (parliament) became a rubber-stamp body for the nationalist party.

A series of political scandals in the 1920s undermined confidence in the government. paving the way for the military to seize power. Unrest and upheaval in Japan in the 1930s gave the military an excuse to firm its grip on power. In February 1936, soldiers assassinated a number of government officials and took control of much of central Tokyo in an effort to make Japan less corrupt and more engaged in international affairs. The rebellion failed but by 1937 a general was prime minister and war was looming large on the horizon.

The military was suspicious of both politicians and corporations. It created a government and a mentality that drove Japan towards war. In " Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma wrote: “When governments rule without popular representation or even consent, one form of rebellion is to be more nationalist that the rulers. If the rulers are traitors to the nation, they should be overthrown.”

Nationalism and Militarism in Japan

"Starting in the late 19th century," historian Ian Buruma wrote in Time, "an official attempt was made to bring all Japanese under one spiritual roof. The nation was taught to follow the imperial cult, called State Shinto: the belief that Japanese Emperor is divine, that the Japanese are descended from their ancient gods, and that any order from a superior---in the government, in the army, at school---must be obeyed without question. State Shinto turned the Japanese state itself into a cult that reached its most extreme from the late 1930s until the end of World War II."

Military leaders rode white horses, wore impressive uniforms and oversaw religious ceremonies in which they communicated with the Sun Goddess while dressed in the robes of a Shinto priest. Classrooms featured shrines with pictures of the Emperor and teachers lectured about he divine ancestry of the Emperor as if it were historical fact. Students were taught self sacrifice was the greatest virtue and killing oneself for one's country was their greatest expression of this. Anyone who opposed "state Shinto" was imprisoned by secret police.

Buruma told the Japan Times: “What Japan began building at the end of the 19th century...is not all that different from extreme forms of Islam because their idea of community is also based on worship, self-sacrifice for the common good, death and so forth.”

Germany and State Shinto

Hitler with Japanese

Germany was the primary model. German language and literature were taught n elite schools not English or France, fascination with Germany also reached the masses. An 1887 magazine article read; “O blow thou German wind! Your approach is felt in scholarship, in the military, in student’s caps, in beer---though why you blow I don know.”

The Japanese parliamentary system was the first of its kind in Asia. Japan’s first general election was held in 1890 but it didn’t produce much lasting effect. Japan’s reborn imperial system was largely German-derived. State-Shintoism was a response to Western Christianity.

Many pre-World-War-II Japanese ideas about nationalism, armed strength, authoritarian rule, territorial expansion and militarism have their roots in Germany. The military was reformed on the Prussian model of modernity: Japan adopted a Civil Code, Commercial Code and bunch of other laws influenced by Germany and France.

The myth of the Japanese Imperial Family's divine origin has traditionally been a basic tenant of Shinto. After Meiji Restoration in 1868, and especially during World War II, Shinto was promoted by the authorities as a state religion (almost the same way that Islam is the state religion in Saudi Arabia).

The historian Ian Buruma told the Japan Times: “State Shinto was deliberately set up in the 19th century as a Japanese version of the Christian church.” The Japanese “were always looking for reasons to explain why the West was so powerful and Japanese thinkers in the 18th century came to conclusion that it all came down to Christianity: It was the church that tied people together and made them obedient to their leaders. So they concluded that what they needed was a national church, and that became State Shinto.”

Over time Shintoism was co-opted from it decentralized animists roots into a state-sponsored war religion. Ian Buruma has suggested that State Shinto was created by “grafting German dogma on Japanese myths. They shared military discipline, mystical monarchism and blood-and-soil propaganda about national essences.”

The Japanese constitution of 1889 declared the emperor sits upon "the throne of a lineal succession unbroken through the ages eternal" and pre-World War II Japanese student were taught that the emperor was a god. Shinto doctrines were taught in school; Shinto shrines were supported by the government; and religion and nationalism developed strong links.

Japanese Colonialism

Emperor Hirohito

reviewing troops The Japanese had traditionally wanted to avoid European and American colonialism and were committed to avoiding what happened to China after the Opium War. They felt humiliated by the unequal treaties that were forced on them by the United States after the arrival of Perry's Black Ships. But in the end Japan became a colonial power itself and Japanese racist views against other Asians worked against it in building a united Asian front against Western imperialism.

The Japanese colonized Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria and islands in the Pacific. After the defeats of China and Russia, Japan began conquering and colonizing East Asia to expand its power. The victory over China in 1895 led to the annexation of Formosa (present-day Taiwan). The victory over Russia in 1905 gave Japan the Liaotang province in China and led the way to the annexation of Korea in 1910. The treaty of Versailles that formally ended World War I gave the Shangdong province in China to Japan.

In some ways, the Japanese mimicked the Western colonial powers. They built grand government buildings and "developed high-minded schemes to help the natives.” Later they even claimed they had the right to colonize. In 1928, Prince (and future Prime Minister) Fumimaro Konoe announced: as a result of [Japan’s] one million annual increase in population, our national economic life is heavily burdened. We cannot [afford to] wait for a rationalizing adjustment of the world system.”

To rationalize their actions in China and Korea, Japanese officers invoked the concept of "double patriotism" which meant they could "disobey moderate policies of the Emperor in order to obey his true interests." A comparison has been made with religious-political-imperial ideology behind Japanese expansion and the American idea of manifest destiny. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Japanese Annexes Korea

In June 1894, Korea sought help from China in putting down a peasant revolt known as the Tonghak Uprising. Japan viewed this as a provocation and sent in its own troops, setting the scene for a confrontation between China and Japan.

In the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 Japan and China fought each other for possession of Korea and Manchuria. Japan won and promised Korea independence. Not long afterward, Russia---coveting warm water ports and taking advantage of China’s weakness---moved into the Korean peninsula.

The Russo-Japanese War in 1904 was also party fought over Korea. The Japanese won again and drove the Russians out of Korea. Their victory demonstrated that they were the unrivaled power in east Asia and the western Pacific. The seizure of Sakhalin island provided a stepping stone from Japan to Korea and Manchuria.

As part of deal that won Teddy Roosevelt a Nobel Peace Prize, Imperial Japan was given a free hand in Korea. The Japanese essentially took control of Korean in 1905 and annexed the country in 1910 after brutally putting down a guerilla insurgency. After the annexation, the Korean army was disbanded, the Japanese resident-general was put in charge of Korea, and a colonial government was established in Seoul, whose name was changed to Keijo.

Japanese Rule and Repression in Korea

Views of Japan in the West The Japanese had hoped to export Japanese settlers and make Korean into a mini-Japan. The Japanese irrigated land and, introduced new seeds and double rice yields. Most of the rice was shipped off to Japan, while Koreans went hungry and in some cases survived by collecting wild plants in the mountains. Coal, forests and other resources were harvested to feed the Japanese economy. Industry was developed with Japan’s interests in mind not Korea’s.

The Imperial Japanese government built roads, ports, dams, power plants, roads, hospitals and schools, improved agricultural output, created an industrial infrastructure and improved health care. Seoul's central train station was built under Japanese imperial rulers in 1925. Some conservative Japanese politicians are angered that Korea is not thankful for all that the Japanese did for them.

The relation between Japan and Korea is sometimes compared with that of Britain and India. The Japanese general generals lived in huge colonial buildings and were chauffeured around in Rolls Royces and horse drawn carriages and escorted by guards with long ceremonial swords. But some argue Japanese rule in Korea was much more brutal.

Before the Japanese arrived there was hardly any industry in Korea. Most of the industry the Japanese introduced was built in the north near coal and metal sources. The location of industry there played a role in dividing the north and south. Before the Japanese occupation both had traditionally been agricultural.

After Korea was annexed, the Japanese used Korean men as slave laborers in the coal mines of the northern Korea. They raped Korean women and dragged them off to brothels in Manchuria, and forced Koreans to renounce their own culture. Much of the old city in Seoul was razed, partly in attempt to obliterate Korean culture, and all but 10 of the 200 buildings that made up the Chosun Dynasty's Kyongbok Palace were destroyed. In 1926, the Japanese built the governor's palace between the Choson throne and the gate of the city, breaking the feng shui line of power on which the city was founded.

The "strong hand of Japan," one Korean villager told reporter Richard Critchfield, destroyed village after village so that "not a single house was left, not a pot unbroken." Japanese police burst into the Korean homes, demanding that parents supply their children as "volunteers" for "comfort stations" and the Imperial Army. Crops were destroyed and families were made so poor they were forced to eat bark and roots, make soap from rice skins, and wear shoes made from wood and straw. [Source: "The Villagers" by Richard Critchfield, Anchor Books]

Japanese Attempts to Eradicate Korean Culture

Under Japanese rule, Koreans were not allowed to speak their language, sing traditional songs or wear traditional clothes. Korean temples and shrines were destroyed, Korean history was banned from schools and Koreans were forced to worship at Japanese Shinto shrines and revere the Japanese emperor.

During the Japanese occupation few children finished grade school. Instead they were forced to do things like take part in fly-killing competitions with the students who killed the most flies winning a prize. In school, Korean children were forced to take Japanese names and study the Japanese language and they were severely punished whenever they uttered a word of Korean.

Recalling those days Korean President Kim Dae Jung said, we "were forced to bow ritually to the picture of the Japanese emperor each day. If we were caught so much as muttering Korean, we were punished, sometimes severely."

Koreans were forced to pledge their loyalty to the Japanese emperor. They weren’t allowed to control anything themselves.

Emperor Hirohito and World War II

Emperor Hirohito The Japanese military committed a number of atrocities in China and Korea and in World War II in the name of the emperor. The conventional wisdom has traditionally been that Emperor Hirohito was a puppet of the military rulers, who ruled Japan from the late 1930s through World War II. He reportedly made no decisions, and was not involved in the running of the government. In 1946, Hirohito said that he "was virtually a prisoner and powerless."

Some historians argue that if Hirohito had stepped in and tried to stop the militarists the move would have only resulted in a coup that would have ousted the feeble civilian government and led to the Emperor's dethronement. Hirohito had been indoctrinated since he was a young man that preserving the emperorship was his most important duty.

Others have argued that Hirohito was not a puppet. Hirohito’s biographer Herbet P. Bix said, "Hirohito was not Hitler or Mussolini. But he was a highly activist, interventionist, dynamic emperor, insisting at all times that he had his say in the making of national policy." Bix believed that the notion of Hirohito as a puppet was propaganda cooked up to serve both Japanese and American interests after the war.

Even though Hirohito tried to prevent Japan from entering the war he was a strong supporter once it got going. He criticized the alliance of Japan with Nazi Germany, supported talks with the U.S. over the cut off of oil and called for restraint on eve of Pearl Harbor but also condemned the army for not conquering more territory in China and was involved in the planning of the Pearl Harbor attack. Hirohito extolled the victims in Singapore, the Philippines and the Pacific, received detailed reports about military planning and offered advice on things like the Bataan Death March and the Battle of Leyte. He used the powers invested in emperor to participate "directly and decisively" in policy making.

Many think that Hirohito was not blamed because the Japanese Constitution stipulated: “The Emperor is sacred and inviolable” which meant that he had no legal responsibility for the war and he was restricted in his input in government policy.

Tojo

Tojo

Gen. Hideki Tojo oversaw Japan military campaign during World War II. He was prime minister during much of the war. Tojo is blamed for launching the war and continuing the fighting when defeat seemed inevitable. He was involved in the Manchurian Incident in 1931 that led to the Japanese takeover of Manchuria and led soldiers into battle in Inner Mongolia in 1937.

Tojo was named war minister in the cabinet of Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on July 1940 and immediately set about making formal studies into a war with the United States. His conclusion: “America, as a nation, has no core. In contrast, our Empire has been in place for 3,000 years.” He also announced the "Senjinkun" (“Field Service Code”) that stated among other things: “Live without the humiliation of being taken prisoner and die without leaving a blemish on your name.” This code prohibited soldiers from being taken prisoner.

Tojo insisted on going to war with the United States, resulting in the fall of the Konoe government. Tojo was picked as Konoe successor and became prime minister on October 16, 1941. As prime minister, Tojo made the decision to go to war with the United States. He served as Prime Minister of Japan during most the war, from October 1941 to July 1944.

As prime minister Tojo established laws the muzzled the press, restricted freedom of speech and controlled gatherings and associations. A writer who complained in an editorial in the Mainichi Shimbun that “we cannot fight with bamboo spears” was drafted and Tojo tried to have him sent to where some of the fiercest fighting was.

Japanese Leaders and the War

Konoe

Most believe that Tojo was the person most responsible for the war. Other Japanese political and military leaders that also bear heavy responsibility for what happened include: 1) Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe; 2) Hajime Sugiyama, the of the Army General Staff; 3) Osamu Nagano, the chief the Naval General Staff; 4) Shigetarro Shimada, navy minister; 5) Takazumi Oka, chief of the Navy Ministry’s Military Affairs Bureau; 6) Shinichi Tanaka, chief of operations at the Army General Staff; 7) Teiich Suzuki, president of the Cabinet Planning Board. Most of these were elite officers in the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army, who graduated from Japan’s Army Academy and the army’s War College and were regarded as elitist and close-minded.

The military was very isolated and bureaucratic. Even when major blundered occurred no one was fired. In the case of the Battle of Midway, commanders who organized the attack remained in their positions after the debacle. The Diet was basically a rubber-stamp body. The media was a vehicle of propaganda rather than voice of skepticism.

Konoe was the prime minister before Tojo, serving from 1937 to 1941. Popular among the Japanese public, he very pro military and made a name for himself with his strong anti-Anglo-American views. He presided over he period when Japan was at war with China. The Marco Polo Incident, regarded as the first beginning if war with China, took place after he took office.

Under the prime ministership of Konoe Fumimaro (1891-1945)--the last head of the famous Fujiwara house--the government was streamlined and given absolute power over the nation's assets. In 1940, the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan, according to tradition, Konoe's cabinet called for the establishment of a "Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere," a concept building on Konoe's 1938 call for a "New Order in Greater East Asia," encompassing Japan, Manchukuo, China, and Southeast Asia. The Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere was to integrate Asia politically and economically--under Japanese leadership--against Western domination and was developed in recognition of the changing geopolitical situation emerging in 1940. (In 1942 the Greater East Asia Ministry was established, and in 1943 the Greater East Asia Conference was held in Tokyo.) Also in 1940, political parties were ordered to dissolve, and the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, comprising members of all former parties, was established to transmit government orders throughout society. In September 1940, Japan joined the Axis alliance with Germany and Italy when it signed the Tripartite Pact, a military agreement to redivide the world that was directed primarily against the United States.[Source: Library of Congress]

Distrust Between the United States and Japan Grows Into War

Koiso

“There had been a long-standing and deep-seated antagonism between Japan and the United States since the first decade of the twentieth century. Each perceived the other as a military threat, and trade rivalry was carried on in earnest. The Japanese greatly resented the racial discrimination perpetuated by United States immigration laws, and the Americans became increasingly wary of Japan's interference in the self-determination of other peoples. Japan's military expansionism and quest for national self- sufficiency eventually led the United States in 1940 to embargo war supplies, abrogate a long-standing commercial treaty, and put greater restrictions on the export of critical commodities. [Source: Library of Congress]

These American tactics, rather than forcing Japan to a standstill, made Japan more desperate. After signing the Japanese-Soviet Neutrality Pact in April 1941, and while still actively making war plans against the United States, Japan participated in diplomatic negotiations with Washington aimed at achieving a peaceful settlement. Washington was concerned about Japan's role in the Tripartite Pact and demanded the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China and Southeast Asia. Japan countered that it would not use force unless "a country not yet involved in the European war" (that is, the United States) attacked Germany or Italy. Further, Japan demanded that the United States and Britain not interfere with a Japanese settlement in China (a pro-Japanese puppet government had been set up in Nanjing in 1940). Because certain Japanese military leaders were working at cross-purposes with officials seeking a peaceful settlement (including Konoe, other civilians, and some military figures), talks were deadlocked. [Ibid]

On October 15, 1941, army minister Tojo Hideki (1884-1948) declared the negotiations ended. Konoe resigned and was replaced by Tojo. After the final United States rejection of Japan's terms of negotiation, on December 1, 1941, the Imperial Conference (an ad hoc meeting convened--and then only rarely--in the presence of the emperor) ratified the decision to embark on a war of "self-defense and self-preservation" and to attack the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor. [Ibid]

Image Sources: National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons; Gensuikan; political cartoons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education; Hirohito pictures, Wikipedia; Kantei, office of Japanese prime minister

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, "Eyewitness to History", edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, "The Good War An Oral History of World War II" by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016