BRUTALITY AND LABOR IN CHINA DURING THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION

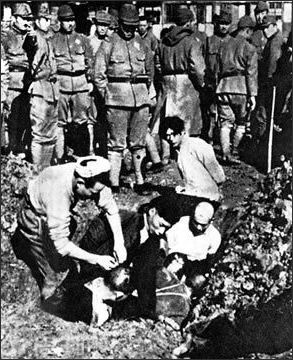

Japanese used dead Chinese for bayonet practice

The Japanese were brutal colonizers. Japanese soldiers expected civilians in occupied territories to bow respectfully in their presence. When civilians neglected to do this they were viciously slapped. Chinese men who showed up late for meetings were beaten with sticks. Chinese women were kidnaped and turned into “comfort women”---prostitutes who serviced Japanese soldiers.

Japanese soldiers reportedly bound the legs of women in labor so they and their children died in horrible pain. One woman had her breast cut off and others were burned with cigarettes and tortured with electric shock, often for refusing to have sex with Japanese soldiers. The Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police, were notorious for their brutality. Japanese brutality encouraged local people to launch resistance movements.

The Japanese forced Chinese to work for them as laborers and cooks. But they generally were paid and as a rule not beaten. By contrast, many workers were dragooned by the Chinese Nationalists and forced to work as laborers under backbreaking conditions, often for no pay. Some 40,000 Chinese were sent to Japan to work as slave laborers. One Chinese man escaped from a Hokkaido coal mine and survived in the mountains for 13 years before he was discovered and repatriated to China.

In occupied China, members of the imperial army’s Unit 731 experimented on thousands of live Chinese and Russian POWs and civilians as part of Japan’s chemical and biological weapons program. Some were deliberately infected with deadly pathogens and then butchered by surgeons without anaesthetic. (See Below)

See Rape of Nanking and Japanese Occupation of China

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; RAPE OF NANKING factsanddetails.com; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; BURMA AND LEDO ROADS factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II” by Laurence Rees Amazon.com; “Japan's Infamous Unit 731: Firsthand Accounts of Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” (Tuttle Classics) by Hal Gold and Yuma Totani Amazon.com; “Unit 731 Testimony: Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” by Hal Gold Amazon.com; "Rape of Nanking The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II" by Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang Amazon.com; “Battle of Shanghai: The Prequel to the Rape of Nanking” by Luke Diep-Nguyen Amazon.com ; “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) Amazon.com; Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com; “The Imperial Japanese Army Volume 1: Japan, the Annexed Territories and Manchuria” by Roderick S. Grigor Amazon.com; “Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism” by Louise Young Amazon.com;

Atrocities During the Japanese Occupation of China

The Japanese committed atrocities in Manchuria that ranked with those Nanking. One former Japanese soldier told the New York Times his first orders after arriving in China in 1940 were to execute eight or nine Chinese prisoners. “You miss and you start stabbing again, over and over.” He said, “There were not many battles with opposing Japanese and Chinese armies Most of the Chinese victims were ordinary people. They were killed or they were left without homes and without food.”

The Japanese committed atrocities in Manchuria that ranked with those Nanking. One former Japanese soldier told the New York Times his first orders after arriving in China in 1940 were to execute eight or nine Chinese prisoners. “You miss and you start stabbing again, over and over.” He said, “There were not many battles with opposing Japanese and Chinese armies Most of the Chinese victims were ordinary people. They were killed or they were left without homes and without food.”

In Shenyang prisoners were kept in contraptions that resembled giant lobster traps with sharp nails imbedded in the ribs. After victims were beheaded their heads were neatly arranged n a line. When asked he could be involved in such atrocities, one Japanese soldier told the New York Times, “We were taught from a young age to adore the emperor, and that, if we died in battle our souls would go to Yasukuni Junja, We just didn’t think anything of killing, of massacres or atrocities. It all seemed normal.”

One Japanese soldier who later confessed to torturing a 46-year-old man suspected of being a Communist spy told the Washington Post, "I tortured him by holding a candle flame to his feet, but he didn't say anything...I put him on a long desk and tied his hands and feet and put a handkerchief over his nose and poured water over his head. When he couldn't breath, he shouted, I'll confess!" But he didn't know anything. "I felt nothing. We did not think of them as people but as objects.”

Kill All, Burn All, Loot All Policy

The Three Alls Policy—Sanko- Sakusen in Japanese—was a Japanese scorched earth policy adopted in China during World War II, the three "alls" being "kill all, burn all, loot all". This policy was designed as retaliation against the Chinese for the Communist-led Hundred Regiments Offensive in December 1940. Contemporary Japanese documents referred to the policy as "The Burn to Ash Strategy" ( Jinmetsu Sakusen). [Source: Wikipedia +]

Chinese burned by Japanese in Nanjing

The expression "Sanko- Sakusen" was first popularized in Japan in 1957 when former Japanese soldiers released from the Fushun war crime internment center wrote a book called The Three Alls: Japanese Confessions of War Crimes in China , Sanko-, Nihonjin no Chu-goku ni okeru senso- hanzai no kokuhaku) (new edition: Kanki Haruo, 1979), in which Japanese veterans confessed to war crimes committed under the leadership of General Yasuji Okamura. The publishers were forced to stop the publication of the book after receiving death threats from Japanese militarists and ultranationalists. +

Initiated in 1940 by Major General Ryu-kichi Tanaka, the Sanko- Sakusen was implemented in full scale in 1942 in north China by General Yasuji Okamura who divided the territory of five provinces (Hebei, Shandong, Shensi, Shanhsi, Chahaer) into "pacified", "semi-pacified" and "unpacified" areas. The approval of the policy was given by Imperial General Headquarters Order Number 575 on 3 December 1941. Okamura's strategy involved burning down villages, confiscating grain and mobilizing peasants to construct collective hamlets. It also centered on the digging of vast trench lines and the building of thousands of miles of containment walls and moats, watchtowers and roads. These operations targeted for destruction "enemies pretending to be local people" and "all males between the ages of fifteen and sixty whom we suspect to be enemies." +

In a study published in 1996, historian Mitsuyoshi Himeta claims that the Three Alls Policy, sanctioned by Emperor Hirohito himself, was both directly and indirectly responsible for the deaths of "more than 2.7 million" Chinese civilians. His works and those of Akira Fujiwara about the details of the operation were commented by Herbert P. Bix in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, who claims that the Sanko- Sakusen far surpassed the Rape of Nanking not only in terms of numbers, but in brutality as well. The effects of the Japanese strategy were further exacerbated by Chinese military tactics, which included the masking of military forces as civilians, or the use of civilians as deterrents against Japanese attacks. In some places, the Japanese use of chemical warfare against civilian populations in contravention of international agreements was also alleged. +

As with many aspects of Japan's World War II history, the nature and extent of Three Alls Policy is still a controversial issue. Because the now well-known name for this strategy is Chinese, some nationalist groups in Japan have even denied its veracity. The issue is partly confused by the use of scorched-earth tactics by the Kuomintang government forces in numerous areas of central and northern China, against both the invading Japanese, and against Chinese civilian populations in rural areas of strong support for the Chinese Communist Party. Known in Japan as "The Clean Field Strategy" (Seiya Sakusen), Chinese soldiers would destroy the homes and fields of their own civilians in order to wipe out any possible supplies or shelter that could be utilised by the over-extended Japanese troops. Almost all historians agree that Imperial Japanese troops widely and indiscriminately committed war crimes against the Chinese people, citing a vast literature of evidence and documentation. +

One Japanese soldier who later confessed to torturing a 46-year-old man suspected of being a Communist spy told the Washington Post, "I tortured him by holding a candle flame to his feet, but he didn't say anything...I put him on a long desk and tied his hands and feet and put a handkerchief over his nose and poured water over his head. When he couldn't breath, he shouted, I'll confess!" But he didn't know anything. "I felt nothing. We did not think of them as people but as objects.”

China’s Japanese-Run 'Auschwitz

Chinese civilains to be buried alive

Taiyuan concentration camp in Taiyuan, capital of north China's Shanxi Province and mining hub about 500 kilometers southwest of Beijing., has been dubbed China’s “Aushwitz.” Tens of thousands died, claims Liu Liu Linsheng, a retired professor who has written a book about the prison. About 100,000 prisoners are said to have passed through its gates.“Some died from starvation and some from illness; some were beaten to death while others died working in places such as the coal mines,” Liu told The Guardian. “The ones who suffered some of the cruellest deaths were those stabbed to death by Japanese soldiers’ bayonets.” [Source:Tom Phillips, The Guardian, September 1, 2015 /*]

Tom Phillips wrote in The Guardian, “As many as 100,000 Chinese civilians and soldiers – including Liu’s father – were captured and confined in the Taiyuan concentration camp by Japan’s imperial army. The Taiyuan camp opened its gates in 1938 – one year after fighting between China and Japan officially broke out – and closed in 1945 when the war ended. It witnessed stomach-churning evils during those years, Liu claimed. Female soldiers were raped or used for target practice by Japanese troops; vivisections were performed on prisoners; biological weapons were tested on unlucky interns. Yet for all those horrors, the prison camp’s existence has been almost entirely wiped from the history books. /*\

“The precise details of what happened in “China’s Auschwitz” remain a blur. There have been no major academic studies of the camp, partly because of the Communist party’s long-standing reluctance to glorify the efforts of its nationalist enemies who did the bulk of the fighting against the Japanese and held Taiyuan when it fell to the Japanese in 1938. Rana Mitter, the author of a book about the war in China called Forgotten Ally, said it was impossible to confirm “every single accusation of every single atrocity” perpetrated by Japanese forces in places such as Taiyuan. “[But] we know through very objective research from Japanese, Chinese and western researchers … that the Japanese conquest of China in 1937 involved tremendous amounts of brutality, not just in Nanjing, which is the famous case, but actually plenty of other places.” /*\

Liu’s father, Liu Qinxiao, was a 27-year-old officer in Mao’s eighth route army when he was captured. “[The prisoners] would sleep on the floor – one next to the other,” he said, pointing to what was once a cramped cell. Zhao Ameng’s father, a soldier named Zhao Peixian, fled the camp in 1940 as he was being taken to a nearby wasteland for execution.” Zhao, whose father died in 2007, recognised that the killing in the Taiyuan prison was not on the same scale as Auschwitz, where more than one million people were killed, most Jews. “[But] the brutality committed in this camp was as bad as in Auschwitz, if not worse,” he said. /*\

Japanese Soldiers in China Towards the End of World War II

Japanese soldiers tie up a young man

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “In spring 1945, Kamio Akiyoshi joined the mortar unit in the Japanese Northern China Area Army's 59th Division. Despite being named the mortar unit, it was actually a field artillery outfit. Divisional headquarters was located on the outskirts of Jinan in Shandong province. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun]

“Drills for new recruits were a daily struggle with heavy items, such as crawling forward while carrying ammunition boxes that weighed 30 kilograms. He was not sent into combat, but on several occasions he saw young peasants brought in on horses, their hands tied behind their backs after being taken captive.

“The 59th Division to which Kamio belonged was one of those Japanese military units that carried out what the Chinese dubbed the "Three Alls Policy": "kill all, burn all, and loot all." One day the following incident took place. "Now we're going to make the prisoners dig holes. You speak Chinese, so go and take charge." This was the order of Kamio's superior officer. Having studied Chinese at a school in Beijing for one year before entering the army, he was happy to have an opportunity to speak the language for the first time in quite a while. He laughed as he dug holes with two or three of their prisoners. "The prisoners must have known that the holes were for burying them after they had been killed. I was far too ignorant to realize." He did not witness their deaths. However, when his unit set off for Korea, the prisoners were nowhere to be seen.

“In July of 1945, his unit redeployed to the Korean Peninsula. After Japan's defeat, Kamio was interned in Siberia. It was another battlefield, where he fought malnutrition, lice, extreme cold, and heavy labor. He was relocated to a camp in the northern Korean Peninsula. Eventually, he was released and returned to Japan in 1948.

Japanese Brutality at the End of the Occupation of China

The Japanese brutality continued right until the end of World War II. In February 1945, Japanese soldiers stationed in China’s Shanxi Province were ordered to kill Chinese farmers after tying them to stakes. A Japanese soldier who killed an innocent Chinese farmer in this way told the Yomiuru Shimbun that he was told by his commanding officer: “Let’s test your courage. Thrust! Now pull out! The Chinese had been ordered to guard a coal mine that had been taken over by Chinese Nationalists. The killing was regarded as a final test in the education of novice soldiers.”

In August 1945, 200 Japanese fleeing the advancing Russian army killed themselves in a mass suicide in Heolongjiang, A woman who managed to survive told the Asahi Shimbun that children were lined up in groups of 10 and shot, with each child making a thud when he or she fell over. The woman said that when her turn arrived the ammunition ran out and she watched as her mother and baby brother were skewered with a sword. A sword was brought down on her neck but she managed to survive.

Buried Poison Gas in China

In August 2003, scavengers in the northwest Chinese city of Qiqhar in Heilongjiang Province tore open some buried containers of mustard gas that had been left by Japanese troops at the end of World War II. One man died and 40 others were badly burned or became seriously ill. The Chinese were very angry about the incident and demanded compensation.

An estimated 700,000 Japanese poison projectiles were left behind in China after World War II. Thirty sites have been found. The most significant is Haerbaling in Dunshua city, Jilin Province, where 670,000 projectiles were buried. Poison gas has also been found buried in several sites in Japan. The gas has been blamed for causing some serious illnesses.

Japanese and Chinese teams have been working together to remove munitions at various sites in China.

China and Japan Face Off Over Documentation of Wartime Atrocities

boy and baby in the ruins of Shanghai

In June 2014, China submitted documentation of the 1937 Nanjing massacre and the Comfort women issue for recognition by UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. At the same time Japan criticized China’s move and submitted documents to UNESCO from Japanese prisoners of war who were held by the Soviet Union. In July 2014, “hina began publicizing the confessions of Japanese war criminals who were convicted by Chinese military tribunals in the early 1950s. The State Archives Administration published one confession a day for 45 days, and each daily release was closely covered by China’s state-run news media. The deputy director of the administration, Li Minghua, said the decision to publish the confessions was in response to Japanese efforts to play down the legacy of the war.

Austin Ramzy of the New York Times wrote: “China and Japan have found yet another forum in which to duel: Unesco’s Memory of the World Register. The Unesco program preserves the documentation of important historical events from various parts of the world. It was started in 1992 and contains items of whimsy — the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz” is one American entry — and terror, such as the records of the Khmer Rouge’s Tuol Sleng prison in Cambodia. While applications to the register have produced disputes — the United States protested the inclusion last year of writings by the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara — they are generally quiet affairs. But China’s submission has led to a high-level debate between the two Asian neighbors. [Source: Austin Ramzy, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, June 13, 2014 ~~]

“Hua Chunying, a spokeswoman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said the application had been filed with “a sense of responsibility toward history” and a goal of “treasuring peace, upholding the dignity of mankind and preventing the reappearance of those tragic and dark days.” Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s chief cabinet secretary, said that Japan had filed a formal complaint with the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo. “After the Imperial Japanese Army went into Nanjing, there must have been some atrocities by the Japanese Army,” he told reporters. “But to what extent it was done, there are different opinions, and it is very difficult to determine the truth. However, China took unilateral action. That’s why we launched a complaint.” ~~

“Ms. Hua said China’s application had included documents from Japan’s military in northeastern China, the police in Shanghai and the Japanese-backed wartime puppet regime in China that detailed the system of “comfort women,” a euphemism used to describe the forced prostitution of women from China, Korea and several Southeast Asian countries under Japanese control. The files also included information on the mass killings of civilians by Japanese troops who entered the Chinese capital of Nanjing in December 1937. China says that about 300,000 people were killed in the weeks-long rampage, which is also called the Rape of Nanking. That figure comes from the postwar Tokyo war crimes trials, and some scholars argue that the toll has been overstated.” ~~

Turning China’s Japanese-Run 'Auschwitz' Into a Memorial

In 2015, China opened the restored Taiyuan concentration camp as a reminder of the terrible things the Japanese did during their occupation of China before and during World War II. What remains today are its last two cellblocks. The names of the Japanese army chiefs responsible for the deaths and atrocities committed at the camp have been carved into the rock in blood-red characters: “This is a murder scene,” Liu told The Guardian. [Source: Tom Phillips, The Guardian, September 1, 2015 /*]

Tom Phillips wrote in The Guardian, “Most of its low-rise brick buildings were bulldozed in the 1950s and replaced by a grimy industrial estate that is to be demolished after years of abandonment. Two surviving cellblocks – surrounded by clusters of high-rise apartments and derelict factories – were used as stables and then storerooms before falling into disrepair. Teams of woodlice patrol empty corridors once policed by Japanese guards. “Many people don’t even know that this place exists,” complained Zhao Ameng. /*\

In preparation for a massive military parade in 2015 to mark 70 years since Japan’s surrender, party officials instructed builders in Taiyuan to turn its ruins into a “patriotic education centre”. Phillips wrote: “China’s decision to restore the Taiyuan prison camp comes as a relief to the children of those who suffered there. Liu has spent nearly a decade campaigning for its few remaining buildings to be protected. But until this year his pleas had fallen on deaf ears, something he and Zhao Ameng blame on powerful real estate developers and officials hoping to cash in on the land. /*\

“During a recent visit to the camp’s ruins Liu wandered through two crumbling shacks where builders were removing armfuls of rotting timber. With the afternoon sun beating down, Liu and Zhao made their way to the banks of Taiyuan’s river Sha and tossed cartons of luxury Zhonghua cigarettes into its fetid waters in homage to their fallen and forgotten fathers. “They were prisoners of war. They weren’t captured at home. They weren’t captured while working in the fields. They were captured on the battlefield fighting our enemies,” said Liu.“Some of them were wounded, some of them were surrounded by enemies and some of them were captured after firing their last round of bullets. They became prisoners of war against their own will. Can you say they are not heroes?” /*\

“For all Beijing’s new-found interest in the story of “China’s Auschwitz”, its retelling is unlikely to extend beyond 1945. For during the Cultural Revolution, the Communist party accused many surviving prisoners of collaborating with the Japanese and branded them traitors. Liu’s father, who had been imprisoned from December 1940 to June 1941, was packed off to a labour camp in inner Mongolia during the 60s and returned a broken man. “My father always said, ‘The Japanese kept me in jail for seven months while the Communist party kept me in jail for seven years,’” he said. “He felt it was very unfair … He felt he had done nothing wrong. I think one of the reasons he died so young – at just 73 – was that he was badly and unfairly treated in the Cultural Revolution.” /*\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, U.S. History in Pictures, Video YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016