JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA

Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, established the puppet government of Manchukuo in 1932, and soon pushed south into North China. The 1936 Xian Incident---in which Chiang Kai-shek was held captive by local military forces until he agreed to a second front with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)---brought new impetus to China’s resistance to Japan. However, a clash between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beijing on July 7, 1937, marked the beginning of full-scale warfare. Shanghai was attacked and quickly fell.* Source: The Library of Congress *]

Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, established the puppet government of Manchukuo in 1932, and soon pushed south into North China. The 1936 Xian Incident---in which Chiang Kai-shek was held captive by local military forces until he agreed to a second front with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)---brought new impetus to China’s resistance to Japan. However, a clash between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beijing on July 7, 1937, marked the beginning of full-scale warfare. Shanghai was attacked and quickly fell.* Source: The Library of Congress *]

An indication of the ferocity of Tokyo’s determination to annihilate the Kuomintang government is reflected in the major atrocity committed by the Japanese army in and around Nanjing during a six-week period in December 1937 and January 1938. Known in history as the Nanjing Massacre, wanton rape, looting, arson, and mass executions took place, so that in one horrific day, some 57,418 Chinese prisoners of war and civilians reportedly were killed. Japanese sources admit to a total of 142,000 deaths during the Nanjing Massacre, but Chinese sources report upward of 340,000 deaths and 20,000 women raped. Japan expanded its war effort in the Pacific, Southeast, and South Asia, and by 1941 the United States had entered the war. With Allied assistance, Chinese military forces---both Kuomintang and CCP---defeated Japan. Civil war between the Kuomintang and the CCP broke out in 1946, and the Kuomintang forces were defeated and had retreated to a few offshore islands and Taiwan by 1949. Mao and the other CCP leaders reestablished the capital in Beiping, which they renamed Beijing. *

5th Anniversary of the Manchurian (Mukden) Incident in 1931Incident

Few Chinese had any illusions about Japanese designs on China. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria in September 1931 and established ex-Qing emperor Puyi as head of the puppet regime of Manchukuo in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its vast potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Nationalist economy. The League of Nations, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of the Japanese defiance. The Japanese began to push from south of the Great Wall into northern China and into the coastal provinces.*

“Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against the Kuomintang government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Nationalist troops (who had been ousted from Manchuria by the Japanese) mutinied at Xi'an. The mutineers forcibly detained Chiang Kai-shek for several days until he agreed to cease hostilities against the Communist forces in northwest China and to assign Communist units combat duties in designated anti-Japanese front areas. *

Of the estimated 20 million people that died as a result of the Japanese hostilities during World War II, about half of them were in China. China claims that 35 million Chinese were killed or wounded during the Japanese occupation from 1931 to 1945. An estimated 2.7 million Chinese were killed in a Japanese "pacification" program that targeted "all males between 15 and 60 who were suspected to be enemies" along with other "enemies pretending to be local people." Out of the thousands of Chinese prisoners captured during the war only 56 were found alive in 1946. *

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; RAPE OF NANKING factsanddetails.com; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; BURMA AND LEDO ROADS factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BRUTALITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) Amazon.com; "Rape of Nanking The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II" by Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang Amazon.com; “Battle of Shanghai: The Prequel to the Rape of Nanking” by Luke Diep-Nguyen Amazon.com; Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com; “The Imperial Japanese Army Volume 1: Japan, the Annexed Territories and Manchuria” by Roderick S. Grigor Amazon.com; “The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904-1932" (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Yoshihisa Tak Matsusaka Amazon.com; “The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905" by Geoffrey Jukes Amazon.com; “Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear: Russia's War with Japan” by Richard Connaughton Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “Imperialism in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries —With a Focus on the Case of Japan in Korea” by John B. Duncan Amazon.com; “Japan's Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism” by Louise Young Amazon.com;

Major Events of the Japanese Occupation of China

Japanese in Shenyang after the Mukden Incident in 1931

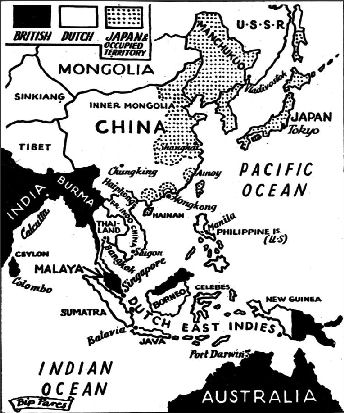

The first phase of the Chinese occupation began when Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931. The second phase began in 1937 when the Japanese launched major attacks on Beijing, Shanghai and Nanking. The Chinese resistance stiffened after July 7, 1937, when a clash occurred between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beijing (then renamed Beiping) near the Marco Polo Bridge. This skirmish not only marked the beginning of open, though undeclared, war between China and Japan but also hastened the formal announcement of the second Kuomintang-CCP united front against Japan. By the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 they were firmly entrenched in China, occupying much of the eastern part of the country.

The Second Sino-Japanese War lasted from 1937 to 1945 and was preceded by a series of incidents between the Japan and China. The Mukden Incident of September 1931—in which Japanese railroad tracks in Manchuria were allegedly bombed by Japanese nationalists in order to hasten war with China—marked the formation of Manchukuo, a puppet state that fell under Japanese administrative control. Chinese authorities appealed to the League of Nations (a precursor to the United Nations) for assistance, but did not receive a response for more than a year. When the League of Nations did eventually challenge Japan over the invasion, the Japanese simply left the League and continued with its war effort in China. [Source: Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org ]

In 1932, in what is known as the January 28th Incident, a Shanghai mob attacked five Japanese Buddhist monks, leaving one dead. In response, the Japanese bombed the city and killed tens of thousands, despite Shanghai authorities agreeing to apologize, arrest the perpetrators, dissolve all anti-Japanese organizations, pay compensation, and end anti-Japanese agitation or face military action. Then, in 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident gave the Japanese forces the justification they needed to launch a full-scale invasion of China. A Japanese regiment was conducting a night maneuver exercise in the Chinese city of Tientsin, shots were fired, and a Japanese soldier was allegedly killed.

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) began with the invasion of China by the Imperial Japanese Army. The conflict became part of World War II, which is also known in China as the War of Resistance Against Japan. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) is known as the Jiawu War in China. It lasted less than a year.

The July 7, 1937, Marco Polo Bridge incident, a skirmish between Japanese Imperial Army forces and China’s Nationalist Army along a rail line southwest of Beijing, is considered the official start of the full-scale conflict, which is known in China as the War of Resistance Against Japan although Japan invaded Manchuria six years earlier. The Marco Polo Bridge incident is also known in Chinese as the “77 incident” for its date on the seventh day of the seventh month of the year. [Source: Austin Ramzy, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, July 7, 2014]

Impact of the Japanese Occupation on China

Chinese fighting in 1937 after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: “Between 14 million and 20 million Chinese died in the “war of resistance to the end” against Japan last century. Another 80 million to 100 million became refugees. The conflict destroyed China’s great cities, devastated its countryside, ravaged the economy and ended all hopes for a modern, pluralistic society. “The narrative of the war is the story of a people in torment,” Rana Mitter, a professor of Chinese history at Oxford University, writes in his superb work, “Forgotten Ally.” [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, September 6, 2013. Chang is the author of “The Coming Collapse of China” and a contributor at Forbes.com]

Few Chinese had any illusions about Japanese designs on China. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria in September 1931 and established ex-Qing emperor Puyi as head of the puppet regime of Manchukuo in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its vast potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Nationalist economy. The League of Nations, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of the Japanese defiance. The Japanese began to push from south of the Great Wall into northern China and into the coastal provinces. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against the Kuomintang government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Nationalist troops (who had been ousted from Manchuria by the Japanese) mutinied at Xi'an. The mutineers forcibly detained Chiang Kai-shek for several days until he agreed to cease hostilities against the Communist forces in northwest China and to assign Communist units combat duties in designated anti-Japanese front areas. *

John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “The only ones really interested in saving China were China’s communists, captained by Mao Zedong, who even flirted with the idea of maintaining an equal distance between Washington and Moscow. But America, blind to Mao’s patriotism and obsessed with its fight against the Reds, backed the wrong horse and pushed Mao away. The inevitable result? The emergence of an anti-American communist regime in China. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, November 15, 2013 -]

How Japan Became a Major Power in Asia

Japan modernized at a much faster rate than China in the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the late 1800s, it was on its way to becoming a world class, industrial-military power while the Chinese were fighting among themselves and being exploited by foreigners. Japan resented China for being a "sleeping hog" that was pushed around by the West.

The world was awakened to Japan's military strength when they defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

The Russo-Japanese war halted European expansion into East Asia and provided an international structure for East Asia that brought some degree of stability to the region. It also changed the world from being a European-centered one to one in which a new pole was emerging in Asia.

Japanese Colonialism

The Japanese hated European and American colonialism and were committed to avoiding what happened to China after the Opium Wars. They felt humiliated by the unequal treaties that were forced on them by the United States after the arrival of Perry's Black ships in the 1853. But in the end Japan became a colonial power itself.

The Japanese colonized Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria and islands in the Pacific. After defeating of China and Russia, Japan began conquering and colonizing East Asia to expand its power.

The Japanese victory over China in 1895 led to the annexation of Formosa (present-day Taiwan) and Liaotang province in China. Both Japan and Russia claimed Liatong. The victory over Russia in 1905 gave Japan the Liaotang province in China and led the way to the annexation of Korea in 1910. In 1919, for siding with the Allies in World War I, the European powers gave Germany's possessions in Shandong province to Japan in the Treaty of Versailles.

The area that Japanese had a right to as a result of its victory in the Russo-Japanese War was quite small: Lunshaun (Port Arthur) and Dalian along with rights to the South Manchurian Railway Company. After the Manchurian Incident, the Japanese claimed the entire area of southern Manchuria, eastern Inner Mongolia and northern Manchuria. The seized areas were about three times the size as the whole Japanese archipelago.

In some ways, the Japanese mimicked the Western colonial powers. They built grand government buildings and "developed high-minded schemes to help the natives.” Later they even claimed they had the right to colonize. In 1928, Prince (and future Prime Minister) Konroe announced: “as a result of [Japan’s] one million annual increase in population, our national economic life is heavily burdened. We cannot [afford to] wait for a rationalizing adjustment of the world system.”

To rationalize their actions in China and Korea, Japanese officers invoked the concept of "double patriotism" which meant they could "disobey moderate policies of the Emperor in order to obey his true interests." A comparison has been made with religious-political-imperial ideology behind Japanese expansion and the American idea of manifest destiny. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Japanese tried to build a united Asian front against Western imperialism but its racist views ultimately worked against it.

Japanese Enter Manchuria

The Japanese operating out of their concessions on China's east coast encouraged and profited from the opium trade. Profits were funneled to right wing societies in Japan that advocated war.

The Japanese operating out of their concessions on China's east coast encouraged and profited from the opium trade. Profits were funneled to right wing societies in Japan that advocated war.

The absence of a strong central government after the collapse of the Qing dynasty made China easy prey for Japan. In 1905, after the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese took over the Manchurian port of Dalien, and this provided a beachhead for its conquests in northern China.

Tensions between China and Japan arose over claims on the Russian-built Manchurian railroad. In 1930, China owned half the railways outright and owned two thirds of the remainder with Russia. Japan held the strategic South Manchurian railway.

The Chinese railroads were built with loans from Japan. China defaulted on these loans. Both China and Japan promised a peaceful resolution to the problem. On the eve of discussions on the matter a bomb exploded on the tracks of the South Manchurian Railway.

Early Events in the Japanese Occupation of China

On March 18, 1926, students in Beiping staged a demonstration to protest the Japanese navy opening fire on Chinese troops in Tianjin. When protesters gathered outside the residence of Duan Qirui, a warlord who was chief executive of the Republic of China at the time, to submit their petition, a shooting was ordered and forty-seven people died. Among them was 22-year-old Liu Hezhen, a student activist campaigning for a boycott of Japanese goods and the expulsion of foreign ambassadors. She became the subject of Lu Xun's classic essay "In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen". Duan was deposed after the massacre and died of natural causes in 1936.

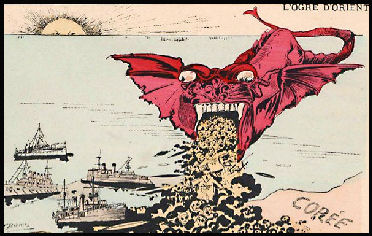

Western view of

Japanese colonialism

In Memory of Miss Liu Hezhen was written by the celebrated and revered left-wing writer Lu Xun in 1926. For decades, it had been in high school textbooks, and there was quite a bit of controversy when education authorities decided to remove it in 2007. There was speculation that the article was junked in part because it might remind people of a similar incident that occurred in 1989.

The Manchurian (Mukden) Incident of September 1931—in which Japanese railroad tracks in Manchuria were allegedly bombed by Japanese nationalists in order to hasten war with China—marked the formation of Manchukuo, a puppet state that fell under Japanese administrative control. Chinese authorities appealed to the League of Nations (a precursor to the United Nations) for assistance, but did not receive a response for more than a year. When the League of Nations did eventually challenge Japan over the invasion, the Japanese simply left the League and continued with its war effort in China. [Source: Women Under Seige womenundersiegeproject.org ]

In 1932, in what is known as the January 28th Incident, a Shanghai mob attacked five Japanese Buddhist monks, leaving one dead. In response, the Japanese bombed the city and killed tens of thousands, despite Shanghai authorities agreeing to apologize, arrest the perpetrators, dissolve all anti-Japanese organizations, pay compensation, and end anti-Japanese agitation or face military action.

Chinese View of the Start of the Japanese Occupation

Protest in Shanghai After Mukden Incident

According to the Chinese government: On September 18, 1931, Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on Shenyang and installed the puppet "Manchukuo" government to control the area. The rigging up of the puppet "Manchukuo" soon gave rise to strong national protest throughout China. Anti-Japanese volunteers, anti-Japanese organizations and guerrilla units were formed with massive participation by Manchu people. On September 9, 1935, a patriotic demonstration was held with a large number of Manchu students in Beijing participating. Many of them later joined the Chinese National Liberation Vanguard Corps, the Chinese Communist Youth League or the Chinese Communist Party, carrying out revolutionary activities on their campuses and outside. After the nation-wide War of Resistance Against Japan broke out in 1937, guerrilla warfare was waged by the Communist led Eighth Route Army with many anti-Japanese bases opened far behind enemy lines. Guan Xiangying, a Manchu general, who was also Political Commissar of the 120th Division of the Eighth Route Army, played a vital role in setting up the Shanxi-Suiyuan Anti-Japanese Base.

Japan Takes Over Manchuria in 1931 After the Manchurian Incident

The Manchurian (Mukden) Incident of September 1931—in which Japanese railroad tracks in Manchuria were allegedly bombed by Japanese nationalists in order to hasten war with China—marked the formation of Manchukuo, a puppet state that fell under Japanese administrative control.

The 10,000-man Japanese Kwantung Army was responsible for guarding the Manchuria railway. In September 1931, it attacked one of its own trains outside Mukden (present-day Shenyang). Claiming that the attack had been carried out by Chinese soldiers, the Japanese used the event---now known as the Manchurian Incident---to provoke a fight with Chinese forces in Mukden and as an excuse to start a full-scale war in China.

The Manchurian Incident of September 1931 set the stage for the eventual military takeover of the Japanese government. Guandong Army conspirators blew up a few meters of South Manchurian Railway Company track near Mukden and blamed it on Chinese saboteurs. One month later, in Tokyo, military figures plotted the October Incident, which was aimed at setting up a national socialist state. The plot failed, but again the news was suppressed and the military perpetrators were not punished.

The instigators of the incident were Kanji Ishihara and Seishiro Itagaki, staff officers in the Kwantung Army, a unit of the Imperial Japanese Army. Some blame these two men for starting World War II in the Pacific. They modeled their attack on the assassination of Zhang Zuolin, a Chinese warlord with a strong influence in Manchuria, whose train was blown up in 1928.

After the Manchurian Incident Japan sent 100,000 troops to Manchuria and launched a full-scale invasion of Manchuria. Japan took advantage of China's weakness. It encountered little resistance from the Kuomintang, taking Mukden in a single day and advancing into Jilin province. In 1932, 3,000 villagers were massacred in Pingding, near Fushan.

Chiang Kai-shek's army offered no resistance against the Japanese after Japan entered Manchuria in 1931. Out of disgrace Chiang resigned as head of the nation but continued on as head of the army. In 1933, he made peace with Japan and attempted to unify China.

Japan Attacks Shanghai

In January 1932, the Japanese attacked Shanghai on the pretext of Chinese resistance in Manchuria. After several hours of fighting the Japanese occupied the northern section of the city and placed the foreign settlement under martial law. Looting and murder prevailed throughout the city, American, French and British troops took up positions with bayonets out of fear of mob violence.

Reporting from Shanghai, an International Herald Tribune reporter wrote: “Terrified by innumerable acts of violence and the persistent rumors of impending Japanese air raids, foreigners kept indoors...Attempting to carry heavy munitions to a secret fortification in the river front, 23 Chinese were killed in a terrific blast which destroyed their craft and shattered windows along the quays, when sparks form the boat’s smokestack ignited the cargo. A live bomb was discovered in the Nanking Theater, Shanghai’s largest movie house, and another bomb, which exploded in the Chinese native city, near the French settlement, did great damage and resulted in grave rioting.”

Finding stiff Chinese resistance in Shanghai, the Japanese waged a three-month undeclared war there before a truce was reached in March 1932. Several days later, Manchukuo was established. Manchukuo was a Japanese puppet state headed by the last Chinese emperor, Puyi, as chief executive and later emperor. The civilian government in Tokyo was powerless to prevent these military happenings. Instead of being condemned, the Guandong Army's actions enjoyed popular support back home. International reactions were extremely negative, however. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations, and the United States became increasingly hostile.

Japanese Occupation of Manchuria

Japanese-built Dalian station

In March 1932, the Japanese created the puppet state of Manchukou. The next year the territory of Jehoi was added. The former Chinese emperor Pu Yi was named the leader of Manchukuo in 1934. In 1935, Russia sold the Japanese its interest in the Chinese Eastern Railway after the Japanese had already seized it. China’s objections were ignored.

Japanese sometime romanticize their occupation of Manchuria and take credit for the great roads, infrastructure and heavy factories they built. Japan was able to exploit resources in Manchuria using the Russian-built trans-Manchurian railway and an extensive network of railroads they built themselves. Vast expanses of Manchurian forest were chopped down to provide wood for Japanese houses and fuel for Japanese industries.

For many Japanese Manchuria was like California, a land of opportunity where dreams could be realized. Many socialists, liberals planners and technocrats came to Manchuria with utopian ideas and big plans. For Chinese it was like the German occupation of Poland. Manchurian men were used as slave laborer and Manchurian women were forced to work as comfort women (prostitutes). One Chinese man told the New York Times, “You looked at the forced labor in the coal mines. There wasn’t a single Japanese working in there. There were great railroads here, but the good trains were for Japanese only.”

The Japanese enforced racial segregation between the themselves and the Chinese and between the Chinese, Koreans and Manchus. Resisters were dealt with using free fire zones and scorched earth policies. Even so Chinese from the south migrated to Manchuria for jobs and opportunities. The pan-Asian ideology given lip service by the Japanese was a view widely held by the Chinese. People ate tree bark. One elderly woman told the Washington Post that she remembered her parents buying her a corn cake, a rare treat at the time, and bursting into tears when someone ripped the cake from her hand and ran off before she had time to eat it.

In November 1936, the Anti-Comintern Pact, an agreement to exchange information and collaborate in preventing communist activities, was signed by Japan and Germany (Italy joined a year later).

Yoshiko Kawashima: China’s Japanese Mata Hari

Yoshiko Kawashima

Kazuhiko Makita of The Yomiuri Shimbun wrote: “ In the bustling coastal metropolis of Tianjin sits the opulent Jingyuan mansion that from 1929 to 1931 was home to Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing dynasty, and also where Yoshiko Kawashima - the mysterious "Eastern Mata Hari" - is said to have had one of her biggest successes. [Source: Kazuhiko Makita, The Yomiuri Shimbun, Asia News Network, August 18, 2013]

Born Aisin Gioro Xianyu, Kawashima was the 14th daughter of Shanqi, the 10th son of Prince Su of the Qing imperial family. Around age six or seven, she was adopted by family friend Naniwa Kawashima and sent to Japan. Known by the name Jin Bihui in China, Kawashima performed espionage for the Kwantung Army. Her life has been the subject of many books, plays and movies, but many anecdotes associated with her are said to be fictional. Her grave is in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Japan, where she lived during her teens.

“Kawashima arrived in Jingyuan in November 1931, right after the Manchurian Incident. The Kwantung Army had already secretly removed Puyi to Lushun, intending to make him head of Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state it was plotting to create in northwest China. Kawashima, the daughter of a Chinese prince, was brought in to help with the removal of Puyi's wife, Empress Wanrong. Kawashima, who grew up in Japan, was fluent in Chinese and Japanese and was acquainted with the empress.

“Despite strict Chinese surveillance, the operation to spirit Wanrong out of Tianjin succeeded, but exactly how remains a mystery. There are no official documents on the operation, but theories abound. One says they slipped out dressed as mourners for a servant's funeral, another says Wanrong hid in the trunk of a car with Kawashima driving, dressed as a man. The success in the plot won Kawashima the trust of the Kwantung Army. Records show she played a role in the Shanghai Incident of January 1932 by helping incite violence between the Japanese and Chinese to create a pretext for the armed intervention by the Imperial Japanese Army.

Kawashima was arrested by Chinese authorities after the war in October 1945 and executed on the outskirts of Beijing in March 1948 for "cooperating with the Japanese and betraying her country". She has a negative image in China, but according to Aisin Gioro Dechong, a descendant of the Qing imperial family who works to preserve Manchurian culture in Shenyang, Liaoning Province: "Her goal was always to restore the Qing dynasty. Her work as a spy was not to help Japan."

Whatever the truth, Kawashima remains a fascinating figure for Chinese and Japanese alike. There are even rumours that the person executed in 1948 was not really Kawashima. "The theory that it wasn't her that was executed - there's lots of mysteries about her that arouse people's interest," says Wang Qingxiang, who researches Kawashima at the Jilin Social l Science Institute. Kawashima's childhood home in Lushun, the former residence of Prince Su, is being restored, and items related to her life are expected to be on display when it opens to the public. Two verses of Kawashima's death poem go: "I have a home but cannot return, I have tears but cannot speak of them".

Image Source: Nanjing History Wiz, Wiki Commons, History in Pictures

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2016