CHINA AND WORLD WAR II

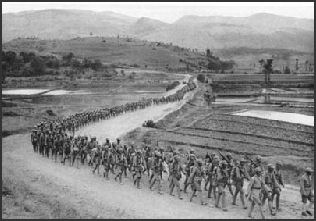

Chinese army marching

Even though the the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) nominally formed a united front to oppose the Japanese invaders in 1937. The struggle between the two parties, which started in 1927, continued openly and hidden from view through the 14-year long Japanese occupation of China (1931-45), The war between the two parties resumed after the Japanese defeat in 1945. By 1949, the CCP occupied most of the country and established the People’s Republic of China the same year. Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek fled with the remnants of the KMT government and military forces to Taiwan, where he proclaimed Taipei to be China's “provisional capital” and vowed to retake the Chinese mainland. Taiwan still calls itself the “Republic of China.” [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The Japanese began their occupation of northern China in1931 and claimed much of coastal China by 1937. When they attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, marking the official beginning of World War II in Asia and the Pacific, the Japanese occupied most of the eastern and coastal part of China but not the interior, some of which they possessed at the end of World War II. The Japanese had difficulty advancing into the interior. In rugged terrain, the well-equipped Japanese were no match for the modestly-armed but determined Chinese peasants. The Kuomintang and Communists formed an alliance against the Japanese. Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists and Mao Zedong's Red Army occupied the interior of China. The area under Mao’s control was home to around 100 million people. Chiang reluctantly agreed to form a United Front with the Communists against the Japanese after being pressured to do so by the United States.

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: ““World War II started not on the plains of Europe but with an accidental firefight in 1937 at the Marco Polo Bridge, a few miles southwest of Beijing. Despite everything — Japanese savagery, Allied indifference, domestic ruin — China under Chiang did not submit to a militarily superior Japan. In fact, Chinese resistance proved crucial in the defeat of the Axis, tying down Japanese forces in what became known as the “China Quagmire.” By the end of the fighting, the Chinese state had regained the sovereignty it had lost in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanjing and assumed its role as one of the Big Four powers that would shape the postwar world. [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, September 6, 2013]

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “When the Japanese War began, the communists in Yen-an and the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek agreed to co-operate against the invaders. Yet, each side remembered its experiences in 1927 and distrusted the other. Chiang's resistance against the invaders became less effective after the Japanese occupied all of China's ports; supplies could reach China only in small quantities by airlift or via the Burma Road. There was also the belief that Japan could be defeated only by an attack on Japan itself and that this would have to be undertaken by the Western powers, not by China. The communists, on their side, set up a guerrilla organization behind the Japanese lines, so that, although the Japanese controlled the cities and the lines of communication, they had little control over the countryside. The communists also attempted to infiltrate the area held by the Nationalists, who in turn were interested in preventing the communists from becoming too strong; so, Nationalist troops guarded also the borders of communist territory. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“American politicians and military advisers were divided in their opinions. Although they recognized the internal weakness of the Nationalist government, the fighting between cliques within the government, and the ever-increasing corruption, some advocated more help to the Nationalists and a firm attitude against the communists. Others, influenced by impressions gained during visits to Yen-an, and believing in the possibility of honest co-operation between a communist regime and any other, as Roosevelt did, attempted to effect a coalition of the Nationalists with the communists.

Of the estimated 20 million people that died as a result of the Japanese hostilities during World War II, about half of them were in China. China claims that 35 million Chinese were killed or wounded during the Japanese occupation from 1931 to 1945. An estimated 2.7 million Chinese were killed in a Japanese "pacification" program that targeted "all males between 15 and 60 who were suspected to be enemies" along with other "enemies pretending to be local people." Out of the thousands of Chinese prisoners captured during the war only 56 were found alive in 1946.

Chinese troops march on Ledo Road

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

Books: "Rape of Nanking The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II" by Chinese-American journalist Iris Chang; “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013); “The Imperial War Museum Book on the War in Burma, 1942-1945" by Julian Thompson (Pan, 2003); “The Burma Road” by Donovan Webster (Macmillan, 2004).

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; Main China Page factsanddetails.com/china (Click History); JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; RAPE OF NANKING factsanddetails.com; BURMA AND LEDO ROADS factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BRUTALITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) Amazon.com; Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com “The Burma Road” by Donovan Webster(Macmillan, 2004) Amazon.com; “Famine, Sword, and Fire: The Liberation of Southwest China in World War II” by Daniel Jackson Amazon.com; “Clash of Empires in South China: The Allied Nations' Proxy War with Japan, 1935-1941 by Franco David Macri Amazon.com; “Chinese Civil War: A History from Beginning to End” Amazon.com “Chiang Kai-shek versus Mao Tse-tung: The Battle for China 1946–1949" (Images of War) by Philip Jowett Amazon.com “China's Civil War: A Social History, 1945–1949" by Diana Lary (Author) Amazon.com “The Imperial War Museum Book on the War in Burma, 1942-1945" by Julian Thompson (Pan, 2003) Amazon.com; “Burma: The Longest War 1941-1945" by Louis Allen Amazon.com; “Flying the Hump: Memories of an Air War” by Otha C. Spencer Amazon.com; “Flying the Hump: The War Diary of Peter H. Dominick” by Alexander S. Dominick | Amazon.com;

Situation in China at the Time of World War II

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “By 1940-1941 Japan had attained her war aim: China was no longer a dangerous adversary. She was still able to engage in small-scale fighting, but could no longer secure any decisive result. Puppet governments were set up in Beijing, Canton, and Nanking, and the Japanese waited for these governments gradually to induce supporters of Chiang Kai-shek to come over to their side. Most was expected of Wang Jingwei, who headed the new Nanking government. He was one of the oldest followers of Sun Yat-sen, and was regarded as a democrat. In 1925, after Sun Yat-sen's death, he had been for a time the head of the Nanking government, and for a short time in 1930 he had led a government in Beijing that was opposed to Chiang Kai-shek's dictatorship. Beyond any question Wang still had many followers, including some in the highest circles at Chongqing (Chungking), men of eastern China who considered that collaboration with Japan, especially in the economic field, offered good prospects. Japan paid lip service to this policy: there was talk of sister peoples, which could help each other and supply each other's needs. There was propaganda for a new "Greater East Asian" philosophy, Wang-tao, in accordance with which all the peoples of the East could live together in peace under a thinly disguised dictatorship. What actually happened was that everywhere Japanese capitalists established themselves in the former Chinese industrial plants, bought up land and securities, and exploited the country for the conduct of their war. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“After the great initial successes of Hitlerite Germany in 1939-1941, Japan became convinced that the time had come for a decisive blow against the positions of the Western European powers and the United States in the Far East. Lightning blows were struck at Hong Kong and Singapore, at French Indo-China, and at the Netherlands East Indies. The American navy seemed to have been eliminated by the attack on Pearl Harbour, and one group of islands after another fell into the hands of the Japanese. Japan was at the gates of India and Australia. Russia was carrying on a desperate defensive struggle against the Axis, and there was no reason to expect any intervention from her in the Far East. Greater East Asia seemed assured against every danger.

“The situation of Chiang Kai-shek's Chongqing (Chungking) government seemed hopeless. Even the Burma Road was cut, and supplies could only be sent by air; there was shortage of everything. With immense energy small industries were begun all over western China, often organized as co-operatives; roads and railways were built—but with such resources would it ever be possible to throw the Japanese into the sea? Everything depended on holding out until a new page was turned in Europe. Infinitely slow seemed the progress of the first gleams of hope—the steady front in Burma, the reconquest of the first groups of inlands; the first bomb attacks on Japan itself. Even in May, 1945, with the war ended in Europe, there seemed no sign of its ending in the Far East. Then came the atom bomb, bringing the collapse of Japan; the Japanese armies receded from China, and suddenly China was free, mistress once more in her own country as she had not been for decades.

Kuomintang and Communists During World War II

In 1932, taking advantage of divisions in China, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria. While Japan moved southward from Manchuria, Chiang chose to campaign against the Communists rather the the Japanese. In the "Xi'an Incident" in December, 1936, Chiang was kidnapped by Nationalist troops from Manchuria and held until he agreed to accept Communist cooperation in the fight against Japan. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists were headquarters in the Yangtze River city of Chongqing. They did little to help the Allied effort against the Japanese. Chiang was more interested in exterminating the Communists and saving his forces for battles against the Communists than ousting the Japanese. Chongqing was China’s capital during World War II in part because it was too far inland for Japanese bombers to reach.

In 1942, Chiang was named the Allied commander in China. The American General Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stillwell, commander of the Allied forces in the China-Burma-India theater, didn't like Chiang at all. He referred to Chiang as a "Peanut" and called him "an unbalanced man with little education...arbitrary and stubborn." In regard to the corrupt and inefficient Kuomintang army he wrote: "The crux of it, they just don't want to get ready to fight...the Chinese government was a structure based on fear and favor." He also compared the fascist ideals of the Nationalist party with those of the Nazi party in Germany.

Chiang Kai-shek's military effort against Japan, as weak it was, won him support from the United States, Britain and even the Soviet Union. Western money and aid didn't seem to make the Kuomintang stronger it just seemed t make them more corrupt and out of touch with Chinese peasantry. A Kuomintang alliance with wealthy landlords didn't win them any support among the peasantry either.

The Communist were based in Yenan in Shanxi Province, the same place they had been since the end of the Long March. During the war Mao described his efforts as "70 percent self-expansion, 20 percent temporization and 10 percent fighting the Japanese.”

Japanese in China

Gen. Stillwell had a higher opinion of the Communists than the Nationalists. "Somehow," General Stillwell wrote, "we must get arms to the Communists, who will fight." The Communists were recruited directly by American forces during a mission to Mao's guerilla base in Yenan on July 23, 1944. A museum devoted to General Stillwell in Chongqing has a picture of an American pilot rescued by the Communists posing next to Mao Zedong.

Communist efforts won the support of the Chinese peasantry, which made up 90 percent of the population of China. By the end of the war, the Communists had recruited nearly a million troops and emerged as a much more powerful force than they were before the war.

Uneasy Kuomintang- Communists Alliance

Lin Biao, one of Mao's top military strategists The collaboration between the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party took place with salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP. The distrust between the two parties, however, was scarcely veiled. The uneasy alliance began to break down after late 1938, despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions, and the rich Chang Jiang Valley in central China. After 1940, conflicts between the Nationalists and Communists became more frequent in the areas not under Japanese control. The Communists expanded their influence wherever opportunities presented themselves through mass organizations, administrative reforms, and the land- and tax-reform measures favoring the peasants--while the Nationalists attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence. [Ibid]

“In 1945 China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but actually a nation economically prostrate and on the verge of all-out civil war. The economy deteriorated, sapped by the military demands of foreign war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by Nationalist profiteering, speculation, and hoarding. Starvation came in the wake of the war, and millions were rendered homeless by floods and the unsettled conditions in many parts of the country. [Ibid]

“The situation was further complicated by an Allied agreement at the Yalta Conference in February 1945 that brought Soviet troops into Manchuria to hasten the termination of war against Japan. Although the Chinese had not been present at Yalta, they had been consulted; they had agreed to have the Soviets enter the war in the belief that the Soviet Union would deal only with the Nationalist government. After the war, the Soviet Union, as part of the Yalta agreement's allowing a Soviet sphere of influence in Manchuria, dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left there by the Japanese. The Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the Communists to move in long enough to arm themselves with the equipment surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army. The problems of rehabilitating the formerly Japanese-occupied areas and of reconstructing the nation from the ravages of a protracted war were staggering, to say the least. [Ibid]

Kuomintang, the Communist and the United States

During World War II, the United States emerged as a major actor in Chinese affairs. As an ally it embarked in late 1941 on a program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist government. In January 1943 the United States and Britain led the way in revising their treaties with China, bringing to an end a century of unequal treaty relations. Within a few months, a new agreement was signed between the United States and China for the stationing of American troops in China for the common war effort against Japan. In December 1943 the Chinese exclusion acts of the 1880s and subsequent laws enacted by the United States Congress to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States were repealed. [Ibid]

“The wartime policy of the United States was initially to help China become a strong ally and a stabilizing force in postwar East Asia. As the conflict between the Nationalists and the Communists intensified, however, the United States sought unsuccessfully to reconcile the rival forces for a more effective anti-Japanese war effort. Toward the end of the war, United States Marines were used to hold Beiping and Tianjin against a possible Soviet incursion, and logistic support was given to Nationalist forces in north and northeast China.

Brutality and Hard Labor During the Japanese Occupation of China

The Japanese were brutal colonizers. Japanese soldiers expected civilians in occupied territories to bow respectfully in their presence. When civilians neglected to do this they were viciously slapped. Chinese men who showed up late for meetings were beaten with sticks. Chinese women were kidnaped and turned into “comfort women”---prostitutes who serviced Japanese soldiers.

Japanese soldiers reportedly bound the legs of women in labor so they and their children died in horrible pain. One woman had her breast cut off and others were burned with cigarettes and tortured with electric shock, often for refusing to have sex with Japanese soldiers. The Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police, were notorious for their brutality. Japanese brutality encouraged local people to launch resistance movements.

The Japanese forced Chinese to work for them as laborers and cooks. But they generally were paid and as a rule not beaten. By contrast, many workers were dragooned by the Chinese Nationalists and forced to work as laborers under backbreaking conditions, often for no pay.

Some 40,000 Chinese were sent to Japan to work as slave laborers. One Chinese man escaped from a Hokkaido coal mine and survived in the mountains for 13 years before he was discovered and repatriated to China.

See Japanese Occupation of China

Barbara Tuchman and Western Perceptions of World War II and China

John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “In 1971, as the Vietnam War reached a critical stage, Barbara Tuchman published a book on the United States and China, “Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45,” which became a bestseller and won the acclaimed historian her second Pulitzer Prize. A vocal opponent of the conflict in Indochina, Tuchman wrote the book in part to instruct Americans on the dangers of backing an Asian tinpot dictator. The United States had made this mistake once before, she contended — during World War II, when it allied itself with the corrupt, incompetent regime of Chiang Kai-shek. It should not do so again. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, November 15, 2013 -]

Barbara Tuchman

“Tuchman’s book was the most influential piece of a slew of scholarship about the United States and China that emerged in the shadow of the war in Vietnam. Even today, the ideas undergirding this scholarship dominate the generally accepted storyline of America’s interactions with the Middle Kingdom. The outlines of that tale are these: The United States tried to help China fight Japan during World War II. But the government that America chose to support was so corrupt and inept that the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt — led on the ground by the heroic U.S. Army Gen. “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell — could do little to get China to fight. Chiang and his commanders avoided battling the Japanese at every turn. -

“Over the past decade and more, however, historians in the United States, Britain, Russia, Taiwan and even China have dismantled Tuchman’s tale piece by piece. New books — from Jay Taylor’s magisterial biography of Chiang, to a solidly researched new work on Mao by Alexander Pantsov and Steven Levine, to research in Chinese and English by historians Michael Sheng, Chen Jian, Qi Xisheng, Yang Kuisong, Sheng Zhihua, Feng Youcai and the late Gao Hua and Ren Donglai — are telling a very different story. First and foremost, Chiang’s armies fought and bled for China, for four years alone against Japan and then for four more years with their American and British allies. One fact alone sums up the truth of this assertion: 90 percent of the casualties on the Chinese side were nationalist troops. -

China: the “Forgotten Ally” ?

John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “Rana Mitter’s new book, “Forgotten Ally,” falls neatly into this welcome new trend and deserves to be read by anyone interested in China, World War II and the future of China’s relations with the rest of the world. A professor of history at Oxford University, Mitter argues that China’s experience during World War II — from the suffering it received at the hands of the Japanese, to the dysfunctional relationship it developed with the United States, to the new demands put on the population by both the nationalist and communist authorities — is critically important to understanding many of China’s issues today. China’s anti-Japanese demonstrations and neuralgia over the Senkaku Islands — a group of uninhabited rocks in the East China Sea administered by Japan but claimed by China — along with its love-hate relationship with America are all rooted in the war, Mitter believes. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, November 15, 2013 -]

In “Forgotten Ally,” he concentrates on the lives of three men: Chiang, Mao and Wang Jingwei, the dashingly handsome Benedict Arnold of modern Chinese history, who, believing resistance to Japan was futile, broke with Chiang in 1938 to lead a quisling government set up by the Japanese. Adding Wang to the mix was a brilliant move because it allows Mitter to explore the three paths taken by the Chinese in the early 20th century as they confronted the challenges of Japanese and Western power. Chiang established strong links to the West, first Germany and then the United States. Mao relied on the Soviet Union, albeit with a fanatical independent streak. Wang believed that China should unite with other Asian nations to counter the marauding white man. Elements of each view remain prominent in the psyche of China today. -

American and Chinese soldier

“Mitter argues that China’s war story has never been told properly. The country has always been portrayed, he writes, as “a minor player, a bit-part actor.” Yet China was the war’s first victim, he notes, two years before Britain and France were attacked and four years before the United States. And while France caved immediately, China stuck it out until the end, valiantly pinning down more than half a million Japanese troops — men and materiel that would have otherwise threatened British India and possibly even the mainland United States. The toll on China alone qualifies as a major story, Mitter notes — 14 million dead, 80 million refugees and the pulverizing of the country’s embryonic modernization. -

“Mitter masterfully constructs these interlocking stories of battles, famines, massacres, diplomacy and intrigue. He sprinkles his narrative with foot soldiers, missionaries, journalists and teachers, showing how the war affected all levels of society throughout China. To detail the famine in Henan in 1942, he uses the powerful reporting of Time magazine’s Theodore H. White, who wrote of “dogs eating human bodies by the roads, peasants seeking human flesh under the cover of darkness.” For Japan’s murderous bombing of China’s wartime capital, Chongqing, Mitter describes the teams of men who pulled bodies out of the rubble and buried them along the banks of the Yangtze River, often tossing a stray limb into its eastward As for Chiang’s tragic decision to dismantle the dikes along the Yellow River to stem the Japanese advance — inundating a territory twice the size of Maryland, killing more than 800,000 and displacing between 3 million and 5 million refugees — Mitter takes the reader down to the unit level. -

“Still, even in a work as groundbreaking as Mitter’s, the misconceptions of the past seem hard to shake. The weakest part of the book is his acceptance of the notion that Mao’s men fought the Japanese. Mitter details only one major communist campaign — the Battle of the Hundred Regiments, which was an absolute failure. Throughout the book, Mitter quotes Mao spouting off about military strategy and even celebrating nationalist defeats. But we never see the communists actually fighting, except for stray claims that they conducted troublesome but unspecified guerrilla campaigns. -

“Mitter even bolsters the counterargument — that Mao kept his powder dry, grew his army and waited to profit from Chiang’s victory. If the communists hit the Japanese so hard, why then did the imperial army not target their revolutionary capital in Yenan more often? From 1938 until late 1941, Mitter reports, Japanese bombers hit it a mere 17 times for a combined death toll of 214. How can this compare with the suffering visited on Chiang’s capital, Chongqing, where 5,000 died in just two days of air raids on May 3 and 4, 1939? “In the end,” Mitter writes, “Chiang won the war but lost his country.” And Mao walked off with the prize. -

Stilwell, China and World War II

CHiang Kai-shek, wife and Stilwell

John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “ The best part of his excellent book is how Mitter dismantles the myth of Joseph Warren Stilwell, the American lieutenant general whom Roosevelt dispatched to China to help lead Chiang’s forces to victory. In “Forgotten Ally,” we see a Stilwell fundamentally at odds with the man lionized in Tuchman’s biography. In Mitter’s artful telling, Stilwell, who had no command experience before his tour in China, comes off as a petulant, small-minded, strategically limited, diplomatically tone-deaf leader obsessed with one thing only: Burma, which, Mitter notes, was “a target of dubious value.” [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, November 15, 2013 -]

“Far from being a strategic visionary, Stilwell committed a string of disastrous military mistakes that resulted in the slaughter of tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers — damaging Chiang’s ability to defend his country first against Japan and later against communist forces backed by the U.S.S.R. Third, it is extremely unclear how much Mao’s forces actually fought the Japanese. Mao’s armies conducted what he called a “sparrow war,” limited to small-scale guerrilla attacks. In fact, the communists lost more troops in attacking their erstwhile nationalist allies than in fighting the Japanese. Finally, there is no ground for believing — as Tuchman did so firmly — that the United States had a chance to pull Mao away from the U.S.S.R.’s embrace. Clearly, this new thesis goes, communism’s rise in China was anything but inevitable; Mao swept to power on the tank treads of the Japanese imperial army. -

“Twice, in 1942 and then two years later, Stilwell strong-armed Chiang into devoting China’s most professionally trained soldiers to quixotic attempts to beat back the Japanese in Burma, each time with disastrous results. In 1944, he compelled Chiang to do so when a Japanese assault — the largest ever conducted by the imperial army — was plowing down China’s east coast. “Let them stew,” came Stilwell’s reply when subordinates pleaded with him for a mere 1,000 tons of supplies to reinforce Chiang’s armies in China’s east. To Mitter, Stilwell’s troubled relationship with Chiang was just the most obvious symptom of a diseased liaison with the United States — a tortured history that he believes continues to bedevil ties between the two giants today. -

Chiang Kai-skek’s Bad Rap and General Stilwell

Sheila Melvin wrote on Caixin Online, “ Chiang was put into impossible military and political positions by an unreliable Washington and the cantankerous “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, the American general in China, who once referred to Chiang as ‘Peanut.’ “It is well known that Stilwell detested Chiang Kai-shek. According to Kuo, this was not only because of the shape of his head, but because Stilwell regarded Chiang as a "little person." His diaries seem to reveal that Chiang Kai-shek was oblivious to Stilwell's disdain. "When Stilwell arrived in Chongqing in March 1942," Kuo explained, "Chiang Kai-shek opened his arms. He saw himself as senior and was willing to educate Stilwell – he told him to be patient and consult, to learn from the experiences of Chinese generals." In his diary, Chiang noted, "I gave Stilwell lessons." Stilwell, however, in his own diary – also in Hoover Institution archives – wrote, "Peanut gave me lessons – bullshit." [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, July 12, 2013]

Chiang Kai-shek and Churchill

In World War II, Chiang was accused of caring little for ordinary Chinese and getting others to fight his battles so he could conserve his forces to fight the Communists after the war. Arthur Waldron wrote: "The negative picture of Chiang can to a certain extent be traced back to one man, the American General Joseph W. Stilwell, whom Roosevelt sent to advise Chiang, and who soon came to despise him. Stilwell, not called Vinegar Joe for nothing... Stilwell was himself the poor strategist: for example, now that we have all the documentation, it is clear that the American four star gravely under-estimated the Japanese in Burma (Myanmar), throwing away tens of thousands of troops in the ill-judged and failed Myitkina offensive. Chiang’s inclination to hold to the defensive was clearly prudent and would have been a better course of action. [Source: Arthur Waldron, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, China Brief (Jamestown Foundation), October 22, 2009]

"A second wellspring of anti-Chiang sentiment was the unhappy American attempt, led by General George C. Marshall, to bring internal peace to post-War China by creating a coalition government between Chiang’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists which foundered for many reasons, one of which was that Marshall had great leverage over Chiang, who depended upon the United States for support, but none whatsoever over the Communists, who were amply supplied by Moscow. Marshall never fully understood this fact, nor did many others. The American ambassador, Leighton Stuart, for example, who had lived in China for decades as an educator and was fluent in the language, believed that ties between the Chinese Communists and Moscow were tenuous and insignificant. [Ibid]

Wang Jingwei and the Japanese Puppet Government

Wang Jingwei (1883 –1944) was a Chinese politician who was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang (KMT), but later became increasingly anti-Communist after his efforts to collaborate with the CCP ended in political failure. His political orientation veered sharply to the right later in his career after he joined the Japanese. He was born as Wang Zhaoming (Wang Chao-ming), but widely known by his pen name "Jingwei" ("Ching-wei"). [Source: Wikipedia +]

Wang Jingwei

Wang was a close associate of Sun Yat-sen for the last twenty years of Sun's life. After Sun's death Wang engaged in a political struggle with Chiang Kai-shek for control over the Kuomintang, but lost. Wang remained inside the Kuomintang, but continued to have disagreements with Chiang until Japan invaded China in 1937, after which he accepted an invitation from the Japanese Empire to form a Japanese-supported collaborationist government in Nanjing. Wang served as the head of state for this Japanese puppet government until he died, shortly before the end of World War II. His collaboration with the Japanese has often been considered treason against China. His name in both mainland China and Taiwan is now a term used to refer to traitors, similar to "Benedict Arnold" for Americans, "Quisling" for Norwegians and "Joaquim Silvério dos Reis" for Brazilians. +

Wang accompanied the Chang Kai-shek government on its retreat to Chongqing during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). During this time, he organized some right-wing groups under European fascist lines inside the KMT. Wang was originally part of the pro-war group; but, after the Japanese were successful in occupying large areas of coastal China, Wang became known for his pessimistic view on China's chances in the war against Japan. He often voiced defeatist opinions in KMT staff meetings, and continued to express his view that Western imperialism was the greater danger to China, much to the chagrin of his associates. Wang believed that China needed to reach a negotiated settlement with Japan so that Asia could resist Western Powers. In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months and announced his support for a negotiated settlement with the Japanese. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek's control. +

On 30 March 1940, Wang became the head of state of what came to be known as the Wang Jingwei regime based in Nanjing, serving as the President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government. In November 1940, Wang's government signed the "Sino-Japanese Treaty" with the Japanese, a document that has been compared with Japan's Twenty-one Demands for its broad political, military, and economic concessions. In June 1941, Wang gave a public radio address from Tokyo in which he praised Japan, affirmed China's submission to it, criticised the Kuomintang government, and pledged to work with the Empire of Japan to resist communism and Western imperialism. Wang continued to orchestrate politics within his regime in concert with Chiang's international relationship with foreign powers, seizing the French Concession and the International Settlement of Shanghai in 1943, after Western nations agreed by consensus to abolish extraterritoriality. +

The Government of National Salvation of the collaborationist "Republic of China", which Wang headed, was established on the Three Principles of Pan-Asianism, anti-communism, and opposition to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang continued to maintain his contacts with German Nazis and Italian fascists he had established while in exile. In March 1944, Wang left for Japan to undergo medical treatment for the wound left by an assassination attempt in 1939. He died in Nagoya on 10 November 1944, less than a year before Japan's surrender to the Allies, thus avoiding a trial for treason. Many of his senior followers who lived to see the end of the war were executed. Wang was buried in Nanjing near the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, in an elaborately constructed tomb. Soon after Japan's defeat, the Kuomintang government under Chiang Kai-shek moved its capital back to Nanjing, destroyed Wang's tomb, and burned the body. Today the site is commemorated with a small pavilion that notes Wang as a traitor.

See Puyi

Kuomintang Soldier Who Fought Against the Japanese

Chinese soldiers with Merill;s Marauders

Yao Yun-long, a veteran of the Republic of China Army who turned 90 in 2013, served as a soldier, non-commissioned officer and officer in the Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang) army for nearly seven years of the war. Yao said he originaly volunteered to join the Youth Army of China upon hearing the appeal from the Republic of China's leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. He began his training with the Three People's Principles Youth League in Zhenping county in central China's Henan province. [Source: Samuel Hui, Want China Times, July 7, 2013 ||||]

"I almost became a patriotic solider like President Ma Ying-jeou's father in the Youth Army," Yao said proudly. "However, everything changed when Zhenping was taken over by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Ichigo Offensive of 1944." Because all government institutions in the county were ordered to retreat, Yao was unable to fight the Japanese in Burma and instead became a guerilla fighter with the Zhenping Self-Defense Corps, a local militia unit. ||||

Samuel Hui wrote in the Want China Times, “Because Yao was the only person in the group who could read and write, he served as the secretary of its commander. Yao said the Zhenping Self Defense Corps sometimes disrupted enemy supply lines on the highway between the provincial cities of Nanyang and Neixiang. With the help of the Loyal Patriotic Army, a special unit trained by the US Navy operating behind enemy lines, the Zhenping Self-Defense Corps was sometimes able to attack Japanese csupply convoys with advanced weapons such as bazookas. ||||

"I personally killed one Japanese soldier in a truck," Yao recalled. "This was my contribution to my beloved motherland during the War of Resistance." The fighting conditions for local militia forces like the Zhenping Self-Defense Corps were terrible. Without a radio, Yao said his unit was liable to be strafed by Allied fighters and bombers. A P-40 Warhawk fighter from the Chinese Air Force thought they were Japanese from the air but thankfully dropped only leaflets on them. "To prevent ourselves from being killed by friendly fire, our commander ordered us to hide whenever we saw an airplane fly past." ||||

Fighting for the Japanese Puppet Army of Wang Jingwei at the End of World War II

Peasant's flee fighting

Yao was ordered by his superior to defect to the Japanese side just two months before the war ended on Aug. 15, 1945. Samuel Hui wrote in the Want China Times, “By June 1945, Wang Chiyuan, commander of the Zhenping Self-Defense Corps, surrendered to the Japanese and the collaborationist government of Wang Jingwei. For this, all of the guerillas including Yao would be considered traitors. "Wang (Chiyuan) told us that he had gained permission from his superior Wang Jingsheng to surrender as a way to protect the lives of the local population," said Yao, "This meant we were actually ordered to be traitors by the central government." [Source: Samuel Hui, Want China Times, July 7, 2013 ||||]

"To be honest, I don't really think Wang Jingwei was a bad guy," Yao said of the man reviled in China as the greatest "Hanjian" or "traitor to the Chinese race" of the 20th century. "While a puppet government was established under Wang's leadership, his collaborationist Chinese army actually protected the people living in occupied China from both the Japanese and [Mao Zedong's] Communists." As Wang Jingwei's government was officially an ally of the Japanese Empire, Yao said Japanese soldiers had no reason to harm Chinese civilians in the regions they occupied. ||||

“In addition, puppet military units — such as the Zhenping Self-Defense Corps now was — were used to suppress local Communist movements as well. "The regular Kuomintang army could not be mobilized against the Communists directly because the United Front still existed at that period of time," Yao said, though the United Front would break down quickly after the Japanese surrender, leading to civil war. "For this reason, I truly believe that Wang Jingwei was doing a favor to Chiang Kai-shek in maintaining the old social order before the War of Resistance (against Japan) began." ||||

"In that period of time, none of us had the chance to choose whether we wanted to be a hero or a traitor," Yao said of his predicament. "I gave my rifle to my superior immediately after I received the order to become a traitor because I did not want to shoot other Chinese soldiers with it." However, Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government would not exonerate the guerilla unit after the Japanese surrendered. Yao was lucky enough to be spared execution but he did not receive the War of Resistance Memorial Medal as other soldiers did. ||||

Comfort Women in China

Between 1932 and the end of World War II in 1945, an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 women served as "comfort women" (sex slaves) for Japanese soldiers in huge Japanese-run brothels. The majority came from Korea. Most of the others came from China and the Philippines as well as Indonesia, Taiwan, Thailand and Burma.

A major center of comfort women activity in China was in Shanghai. The South China Morning Post reported in 2017: “With its red-painted window frames and sooty facade, the empty two-storey building on Gongping Road is typical of many of Shanghai’s pre-second world war structures – but this one houses dark memories. The crumbling mansion is one of 150 sites in the city formerly used as “comfort stations”, part of the vast system of sexual slavery established by Japan for its invading armed forces before and during the war. About 30 are believed left in the city, but these silent witnesses to history are disappearing amid rapid urban development and China’s hesitance to memorialise the painful episode. [Source: South China Morning Post, March 8, 2017]

Su Zhilian of Shanghai Normal University, “has waged a crusade to spotlight the suffering of sex slaves. When he first began delving into the issue in the early 1990s, authorities prevented Su from publishing his research. “The Chinese government has really not done enough. This is a wartime human rights issue, but in order to maintain good relations with Japan the government does not give the issue much support,” Su said. He now raises money for survivors, of whom there are only 17 known in China, none in Shanghai. Many were stigmatised and ostracised after the war, receiving no special government assistance.

“A former “comfort station” in Nanjing, 300km west of Shanghai, was converted into a museum by local authorities, opening in December 2015. Su, meanwhile, was granted permission to upgrade his display of archives into a museum, which opened in October in a building on his campus. Just outside, a statue representing two sex slaves – one Chinese, one Korean – was unveiled. China has also recently made available documents on sex slaves from its official archives, amid an international effort to include them in the Unesco International Memory of The World Register.

Also in 2017, footage of comfort women in Yunnan was revealed. What's on Weibo reported: “Moving images have been made public that show Korean women imprisoned by the Japanese army in China, where they served as comfort women. The 18-second-clip made its rounds on Chinese social media. The footage was filmed in Yunnan province, in southwest China, in 1944. Previously, there were numerous texts and photographs documenting the imprisonment of comfort women in China, but this is the first time for these moving images to be made public showing these particular scenes of wartime China. A South-Korean research group, consisting of members of the Seoul Metropolitan Government and the Seoul National University Human Rights Center, made the footage public. Researchers say the clip shows seven Korean women in front of a private house used as a “comfort station” in Songshan, Yunnan Province.

COMFORT WOMEN: THEIR STORIES, TREATMENT AND POLITICAL BATTLES See Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Fighting and Japanese Brutality at the End of the Occupation of China

In late 1944, the Japanese stepped up their fighting in China as part of an effort to wipe out forward bases for the United States Air Force. Between September 8 and November 26, 1944, seven large air bases were overrun by the Japanese. Less than a month later the Japanese split unoccupied China and opened up new route that allowed the Japanese to travel between Singapore and Korea

In the spring of 1945, the Chinese began a counteroffensive that regained much of the territory lost the previous year. Imperative to this drive were 35 divisions trained and supplied with the help of Gen. Stillwell. Air support was provided by American and British planes based in Luichow, India and Kunming, China.

In contrast to the devastating defeats the Japanese suffered in the Pacific the Japanese were largely able to hold their own in China and were able to mount an effective offensive into the spring of 1945. At the time of surrender Japan held about half of China and the attacks by Nationalist and Communists were little more than harassments,"When the Americans were here, it was pretty peaceful, a member of the Dai hill tribe told the New York Times in 1995, "For a while, we used American money. I remember because American coins were so big.

China in October 1944

The Japanese brutality continued right until the end of World War II. In February 1945, Japanese soldiers stationed in China’s Shanxi Province were ordered to kill Chinese farmers after tying them to stakes. A Japanese soldier who killed an innocent Chinese farmer in this way told the Yomiuru Shimbun that he was told by his commanding officer: “Let’s test your courage. Thrust! Now pull out! The Chinese had been ordered to guard a coal mine that had been taken over by Chinese Nationalists. The killing was regarded as a final test in the education of novice soldiers.”

In August 1945, 200 Japanese fleeing the advancing Russian army killed themselves in a mass suicide in Heolongjiang, A woman who managed to survive told the Asahi Shimbun that children were lined up in groups of 10 and shot, with each child making a thud when he or she fell over. The woman said that when her turn arrived the ammunition ran out and she watched as her mother and baby brother were skewered with a sword. A sword was brought down on her neck but she managed to survive.

Last Minute Scramble by the Soviet Union in China as World War II Ends

At Yalta in February 1945, Stalin demanded that the Soviet Union be given Mongolia and Manchuria in return for cooperation with an Allied invasion of Japan. Stalin also signed a treaty with Chiang Kai-shek that gave Soviet support to the Kuomintang not the Communists. After the war in Europe was finished in May 1945, Soviet forces moved against the Japanese in Manchuria. The Soviet Union declared war on Japan two days after the Hiroshima bomb was dropped. In a massive offensive that began the next day on August 9, Soviet forces moved into Manchuria and occupied it and southern Sakhalin and the Kuril islands. The Japanese occupation of China ended with Japan's total surrender after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

One man in Harbin in northeastern China told writer Paul Theroux:: "It all ended in 1945, when the Japanese front collapsed. The Russian soldiers, who had been criminals and prisoners, were unmerciful. They took the city and began raping and murdering." Around 600,000 Japanese were taken to Siberia as prisoners. About 55,000 died in prison. Survivors endured slave labor, starvation and bitter cold. A few managed to make it back to Japan. Many remained in the Soviet Union after their release from prison.

Manchuria Soviet Offensive

In a review of “China 1945: Mao's Revolution and America's Fateful Choice” by Richard Bernstein, John Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “Bernstein tells the story of the United States, China, Japan and the U.S.S.R. during the last, dramatic year of World War II in Asia... The crucial event in this story, Bernstein says, occurred one minute after midnight on Aug. 9, 1945, when 11 army groups from the Soviet Union, backed by 27,000 artillery pieces, 5,500 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 3,700 aircraft — 1 million soldiers shouting “Death to the Samurai!” — invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria in one of the great operations of World War II. Japan’s famed Kwantung Army was crushed. Because the invasion took place only three days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the United States, it’s been forgotten by history. But, Bernstein argues persuasively, the Soviet occupation of Manchuria — urged, ironically, by President Franklin Roosevelt and powered by Lend-Lease supplies — was “the dominant force shaping China and China’s future relations” with the United States and the Soviet Union. Immediately after Stalin’s occupation, Mao’s forces flooded Manchuria; Stalin’s Red Army handed over a treasure trove of Japanese weaponry and allowed the communists to recruit tens of thousands of soldiers as they prepared for the civil war with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, December 12, 2014 /]

“Once Stalin’s armies occupied China’s northeast, any chance that Mao would settle for a deal with the beleaguered Nationalist Party of Chiang evaporated, regardless of the herculean efforts of George Marshall, who was dispatched to China by President Harry Truman. From that point on, Mao knew he was going to prevail, Bernstein says. “China may . . . have been ‘lost’ by Chiang Kai-shek, but mainly it was won by Stalin and his loyal acolyte, Mao.” /

Book: "China 1945: Mao’s Revolution and America’s Fateful Choice" by Richard Bernstein, Knopf, 2014.

Impact of the Japanese Occupation and World War II on China

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: “The war did more than ruin the country and set the stage for a Communist dictatorship. In the early decades of the 20th century, Mitter writes, “many felt that China was a geographical expression rather than a country.” The invasion by the Japanese — once mentors to the Chinese but now seen as monsters — created a sense of national identity. In 1938, after the first Nationalist battlefield victory, China’s people for the first time began to care who governed them. The nation may have been in disarray, but “China” as a concept became personal and meaningful. During the war, it had often looked as if China would “have no more history,” as one leading political figure put it. Yet in 1945 the Chinese, Mitter notes, “at last had the power to write the next chapter of their story.” [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, September 6, 2013]

“The victorious Nationalist China of Chiang Kai-shek arguably lost more than the vanquished Japan. By 1949, Chiang had fled to Taiwan and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party had taken control. Throughout his book, Mitter discusses a “new compact between state and society,” as the country became “more militarized, categorized and bureaucratized.” Because of the exigencies of the fighting, the rival Nationalists and Communists demanded much more from populations under their control than had traditionally been the case, yet at the same time leaders were expected to provide more in return.

“In addition, the war effort required mass mobilization, and this soon came to define the Communists, shaping their rule, first in their home base of Yan’an and then, once they prevailed, throughout the country. Mitter argues that the experiences of the war marginalized those in the Communist Party who were hoping for a more tolerant style of government. The horrors of conflict, first with the Japanese and then between the Nationalists and the Communists, reinforced in the minds of government officials the fear of disorder that persists today.

Communist Eight Route Army in Shanxi

“The war also instilled in China a lasting hatred of the Japanese. They may no longer be called “dwarf bandits,” as they were during the great conflict, but even now Chinese “resentment can flare up suddenly, and seemingly without immediate cause.” As Mitter says, “the war’s legacy is all over China today, if you know where to look.” He is correct, of course. Still, anti-―Japanese sentiment is prevalent in China today largely because of indoctrination ordered by fundamentally weak leaders seeking to bolster their rule through nationalism. And even if the more tolerant Communists Mitter describes had won out, it is unlikely that any form of Chinese Communism would have been liberal or benign, especially with the dominating Mao Zedong as its leader. Mitter did not have to wade into the complications of present-day China, but having done so he should have put his judgments into firmer context.

China’s Position on Japan and World War II

The San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951 signified Japan's return to the community of nations as a reformed state. It was signed by the United States, Japan, Taiwan, the Soviet Union and 48 other nations but not by China. The treaty allowed Japan to once again control its domestic and foreign affairs. It also limited reparation claims against Japan by victims such as POWs and comfort women and required Japan to abide by anti-aggression provisions in the United Nations charter.

Many Chinese feel the Japanese need to apologize for the Rape of Nanking, Unit 731 and other atrocities committed in China. In 1970, Chinese textbook claimed that 10 million people died in China during World War II.The figure increased to 35 million in 2000.

Austin Ramzy of the New York Times wrote: “China has accused Japan of failing to fully come to terms with its wartime aggression and has questioned the sincerity of its apology for the sexual slavery of women from China, Korea and other parts of Asia during the war. Visits by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan and other Japanese officials to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which honors the nation’s war dead, including several Class A war criminals, routinely set off complaints from China and South Korea.” [Source: Austin Ramzy, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, July 7, 2014 |+|]

In July 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke at a ceremony in Beijing marking the 77th anniversary of Japan’s war with China, and condemned efforts to revise views of Japan’s history of military aggression. “History is history, and facts are facts. Nobody can change history and facts,” Mr. Xi said during the ceremony at a war museum in suburban Beijing, which was attended by students, officials and war veterans. “Chinese people who have made such a great sacrifice will not waver in protecting a history written in sacrifice and blood. Anyone who wants to deny, distort or beautify the history of the invasion will definitely not find agreement from the people of China or the rest of the world.”[Source: Austin Ramzy, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, July 7, 2014 |+|]

Ramzy wrote: “As tensions between China and Japan remain high over territorial disputes, China has sought to publicize Japan’s brutal wartime occupation, a reminder of how the past is never far behind in the relationship between the two Asian powers. While Mr. Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, also participated in war memorial events, it was typically on dates that were commemorated internationally, such as the 2005 observances marking the 60th anniversary of the end of the war or the 65th anniversary in 2010.” The event that Xi spoke at “marked the anniversary of the July 7, 1937, Marco Polo Bridge incident” which “is considered the official start of the full-scale conflict, which is known in China as the War of Resistance Against Japan.” |+|

Japan's Position on China and World War II, Textbooks and Compensation

Rape of Nanking

Many Japanese feel their actions in China, the Philippines and Southeast Asia II are no worse than those committed by colonizing Western nations such as Britain, France, Portugal, Spain, the U.S. and the Netherlands. Some Japanese feel it is unfair that they have to apologize while other colonizing nations do not. The Japanese can make a credible argument that Japan "liberated" Asian counties such as China, Burma and Indonesia from "white imperialism.” Japanese conservatives claim there is a lack of proof for things like the Rape of Nanking, Unit 731 and comfort women, and claim the Japanese occupation brought progress and development to Korea, China and other nations. . In the mid 2000s, Japanese began traveling to China on tours of sites were wartime atrocities and massacres occurred. Among the stops on a Manchuria tour were the remains of Unit 731.

In Japanese textbooks from the 1980s the only reference to the "Rape of Nanking" was a footnote that called it the "Nanking Incident." In the same textbooks the Japanese occupation of China was referred to as the "China Incident," and characterized by skirmishes between Japanese and Communists and "bandits." Chinese textbooks are not known for their forthrighteousness or accuracy either. Some teach that Mao defeated the Japanese in World War II. Japanese history textbooks introduced in the mid 1990s admitted that Japan "waged a war of aggression" as a "fascist state" in conjunction with Nazi Germany and Italy. The books included descriptions of the "Rape of Nanking," Unit 731, and said that the Japanese government was "determined to...fight to the death on Japanese soil, whatever sacrifices that might mean for the people."

Another textbook that addressed the sex slave issue said, "Young women from Korea and other countries were conscripted as comfort women and sent to the war front." Another said: "The Japanese forces acted cruelly in various places in China. In particular, when they occupied Nanking, they indiscriminately killed civilians, including soldiers who had thrown out their arms, older people, women and children. The number of dead is said to be over 100,000 and is estimated to be over 300,000 in China."

In March 2003, a Niigata District Court ordered the the Japanese government and a Japanese company to pay ¥88 million in compensation to Chinese who were forced to labor in Japan during World War II. In April 2007, the Japanese Supreme Court ruled that the 1972 Japan China Joint Communique prevented Chinese individuals from seeking war compensation through the Japanese courts and dismissed claims by Chinese who were forced to work as laborers for a Japanese firm during World War II. The decision overturned a lower court ruling that said that Japan was required to pay war compensation. The ruling also affected claims for by comfort women. In July 2005, a Japanese court rejected a demand to set up a fund for Japanese war orphans left in China after World War II. The orphans now in their 60s and 70s had wanted $300,000 and blamed the government for not making an effort to repatriate them In July 2005, a Tokyo court ruled that the Japanese government was responsible for paying damages to China for atrocities carried out by a notorious germ warfare unit in World War II. The suit was brought by 180 Chinese plaintiffs. Japan has never acknowledged carrying out the attacks.

See Separate Article LACK OF APOLOGIES, JAPANESE TEXTBOOKS, COMPENSATION AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

Documentary About Comfort Women a Big Hit in China

World War II Destruction in China “Twenty-Two”, a documentary about comfort women in China released in 2017, turned out to be a relatively big hit in China. Pang-Chieh Ho wrote in Sup China: When “Twenty-Two”, a documentary that interviews 22 surviving World War II sex slaves, debuted in mainland Chinese theaters nobody had expected that it would be such a big hit with Chinese moviegoers. Made from a paltry budget of 3 million yuan ($450,000), “Twenty-Two” managed to buck expectations. Not only is it the first documentary to make more than 100 million yuan ($15 million) at China’s box office, according to Mtime, but if it ends up grossing 300 million yuan ($45 million), a goal that analysts are confident the documentary will attain, it will also become the most profitable Chinese movie of all time. [Source: Pang-Chieh Ho Sup China, February 28, 2017]

“This dark horse of a film has had a somewhat turbulent production history. While filming and interviewing the octogenarian survivors took around two months, the movie was waylaid for several years due to a lack of financing, according to The Paper’s interview with Twenty-Two’s director, Guo Ke . When financing finally came through, a large part of it was in the form of crowdsourcing, with over 7,000 people contributing 1 million yuan ($150,000) to the movie.

“So how did this documentary — one that eschews sensationalism in favor of quiet documentation of the everyday lives these former “comfort women” are now leading — become a force to be reckoned with at the box office? Yuledujiaoshou points out that strong word of mouth and high critical ratings have been essential toTwenty-Two’s success, while personal recommendations from many industry figures, including director Feng Xiaogang and actress Zhang Xinyi, who invested 1 million yuan ($150,000) in the movie, helped boost the movie’s exposure. Also, the movie’s shrewd choice of a premiere date — on the eve of the International Memorial Day for Comfort Women and the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II — dovetailed with sentiments of patriotism and nationalism that had already been stoked by another film, Wolf Warriors 2.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, U.S. National Archives and When Tigers Roared veterans group and History in Pictures, Video YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021