EARLY ASIANS

Niah Caves

The first people to inhabit Southeast Asia, anthropologists believe, were dark-skinned, curly-haired hunter-gatherers similar to people found in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands Australia and Melanesia. They were late displaced by Chinese. The only survivors of the original hunter gathers that inhabited Southeast Asia are Semang Negritos of peninsular Malaysia and the Negritos of the mountains of Luzon and some islands of the Philippines.

Land ridges existed as late as 20,000 years, when seas levels were 120 to 130 meters lower than they are now. Some scholars have speculated that flood myths, common among many Southeast Asian minorities, as well as in the Bible, may have originated in Southeast Asia and refer to flooding caused by rising seas after the Ice Age. Most well-known early Neolithic sites in Southeast Asia are in protected caves. Many good sites are believed to date back to the ice age and are now underwater. [Book: “The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia” by Stephen Oppenheimer (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1999)]

The charred bones of orangutans have been found in at 40,000 archaeological sites at Niah Caves in Malaysian Borneo. Evidence of human habitation, estimated at around 33,000 year old, has also been found at Golo and Wetef Island (northwest of New Guinea), coastal Sulawesi, the northern coast of New Guinea, the Bismark Archipelago (northeast of New Guinea), and the northern Solomon Islands (southeast of New Guinea),

Until roughly 4000 B.C. Southeast Asia was still occupied by hunter gatherers making pebble and flake stone tools. Spirit Cave, which overlooks a steam running into the Salween River near the Thai-Burmese border, was occupied 14,000 to 7,500 years ago by people who hunted deer, pigs, monkeys, bamboo rats, otters and flying squirrel, caught fish and crabs, and ate melons and beans. The Spirit Cave people used scrapers choppers and flakes and fairly sophisticated stone knives and tools called adzes. Archaeologists also found a poison made from plants that are relatives of the caster-oil family that may been used for poisoning arrowheads or darts. Nine-thousand-year-old pottery was also found in Spirit Cave. It is as old as samples found Japan, often regarded as the home of the oldest pottery in the world.

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

40,000 Year Old Cave Art Found in Sulawesi, Indonesia

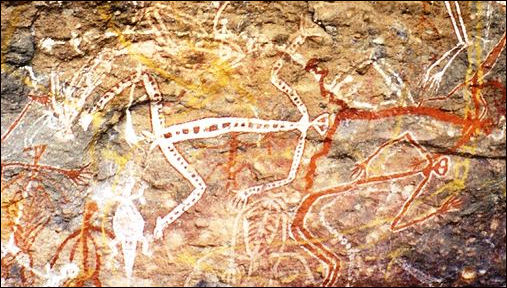

Remains at Niah Cave show that men have been living on Borneo for a long time. In the karst interior of Borneo are networks of caves with rock art and hand prints, some of them dated to 12,000 years ago. More significantly, rock art and hand prints found in caves in Sulawesi have been dated to nearly 40,000 years ago. Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Archaeologists working in Indonesia say prehistoric hand stencils and intricately rendered images of primitive animals were created nearly 40,000 years ago. These images, discovered in limestone caves on the island of Sulawesi just east of Borneo, are about the same age as the earliest known art found in the caves of northern Spain and southern France. The findings were published in the journal Nature. "We now have 40,000-year-old rock art in Spain and Sulawesi," said Adam Brumm, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and one of the lead authors of the study. "We anticipate future rock art dating will join these two widely separated dots with similarly aged, if not earlier, art." [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

“The ancient Indonesian art was first reported by Dutch archaeologists in the 1950s but had never been dated until now. For decades researchers thought that the cave art was made during the pre-Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. "I can say that it was a great — and very nice — surprise to read their findings," said Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. "'Wow!' was my initial reaction to the paper." ~\~

Hand prints in Pettakere Cave in Sulawesi

The researchers said they had no preconceived ideas of how old the rock art was when they started on this project about three years ago. They just wanted to know the date for sure. To do that, the team relied on a relatively new technique called U-series dating, which was also used to establish minimum dates of rock art in Western Europe. We have seen a lot of surprises in paleoanthropology over the last 10 years, but this one is among my favorites. - Wil Roebroeks, Leiden University archaeologist

First they scoured the caves for images that had small cauliflower-like growths covering them -- eventually finding 14 suitable works, including 12 hand stencils and two figurative drawings. The small white growths they were looking for are known as cave popcorn, and they are made of mineral deposits that get left in the wake of thin streams of calcium-carbonate-saturated water that run down the walls of a cave. These deposits also have small traces of uranium in them, which decays over time to a daughter product called thorium at a known rate. "The ratio between the two elements acts as a kind of geological clock to date the formation of the calcium carbonate deposits," explained Maxime Aubert of the University of Wollongong in Australia's New South Wales state, the team's dating expert. ~\~

“Using a rotary tool with a diamond blade, Aubert cut into the cave popcorn and extracted small samples that included some of the pigment of the art. The pigment layer of the sample would be at least as old as the first layer of mineral deposit that grew on top of it. Using this method, the researchers determined that one of the hand stencils they sampled was made at least 39,900 years ago and that a painting of an animal known as a pig deer was at least 35,400 years old. In Europe, the oldest known cave painting was of a red disk found in a cave in El Castillo, Spain, that has a minimum age of 40,800 years. The earliest figurative painting, of a rhinoceros, was found in the Chauvet Cave in France; it goes back 38,827 years. ~\~

“The unexpected age of the Indonesian paintings suggests two potential narratives of how humans came to be making art at roughly the same time in these disparate parts of the world, the authors write. It is possible that the urge to make art arose simultaneously but independently among the people who colonized these two regions. Perhaps more intriguing, however, is the possibility that art was already part of an even earlier prehistoric human culture that these two groups brought with them as they migrated to new lands. One narrative the study clearly contradicts: That tens of thousands of years ago prehistoric humans were making art in Europe and nowhere else "The old 'Europe, the birthplace of art' story was a naive one, anyway," said Roebroeks. "We have seen a lot of surprises in paleoanthropology over the last 10 years, but this one is among my favorites." ~\~

Early Modern Man in India

Jwalapurum

Pakistan and India lie on the postulated southern coastal route followed by anatomically modern H. sapiens out of Africa, and so may have been inhabited by modern humans as early as 60,000-70,000 years ago. There is evidence of cave dwellers in Pakistan’s northwest frontier, but fossil evidence from the Paleolithic has been fragmentary. [Source: Glorious India]

In 2005, Brian Vastag of National Geographic News wrote: “Modern humans migrated out of Africa and into India much earlier than once believed, driving older hominids in present-day India to extinction and creating some of the earliest art and architecture, a new study suggests. The research places modern humans in India tens of thousands of years before their arrival in Europe. University of Cambridge researchers Michael Petraglia and Hannah James developed the new theory after analyzing decades' worth of existing fieldwork in India. They outline their research in the journal Current Anthropology. "He's putting all the pieces together, which no one has done before," Sheela Athreya, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University, said of Petraglia. [Source: Brian Vastag, National Geographic News, November 14, 2005]

“Modern humans arrived in Europe around 40,000 years ago, leaving behind cave paintings, jewelry, and evidence that they drove the Neanderthals to extinction. Petraglia and James argue that similar events took place in India when modern humans arrived there about 70,000 years ago.The Indian subcontinent was once home to Homo heidelbergensis, a hominid species that left Africa about 800,000 years ago, Petraglia explained. "I realized that, my god, modern humans might have wiped out Homo heidelbergensis in India," he said. "Modern humans may have been responsible for wiping out all sorts of ancestors around the world." "Our model of India is talking about that entire wave of dispersal," he added. "That's a huge implication for paleoanthropology and human evolution." Petraglia and James reached their conclusions by pulling together fossils, artifacts, and genetic data.

See Separate Article: FIRST HOMININS AND HUMANS IN INDIA factsanddetails.com

North-South Genetic Divide Among Native Populations in East Asia

Chinese researchers Feng Zhang, Bing Su, Ya-ping Zhang and Li Jin wrote in an article published by the Royal Society: “East Asia is one of the most important regions for studying evolution and genetic diversity of human populations. Its importance is associated with the extensive presence of humans and their claimed ancestors over the last 2 million years, and with being the crossroads connecting America and the Pacific Islands. [Source: “Genetic studies of human diversity in East Asia” by 1) Feng Zhang, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, 2) Bing Su, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, 3) Ya-ping Zhang, Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-resource, Yunnan University and 4) Li Jin, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University. Author for correspondence (ljin007@gmail.com), 2007 The Royal Society ***]

“China, one of the centres of human civilization, comprises most of the geographical span, ethnic groups and languages of East Asia. In the past two decades, much effort has been made by researchers in China and their international collaborators to characterize the structure of genetic diversity of human populations in China. The most significant progress of such studies started with the observation of genetic distinction between the southern and the northern East Asian populations (Zhao et al. 1987). ***

In recent years researchers in China have made substantial efforts to collect samples and generate data especially for markers on Y chromosomes and mtDNA. The hallmark of these efforts is the discovery and confirmation of consistent distinction between northern and southern East Asian populations at genetic markers across the genome. With the confirmation of an African origin for East Asian populations and the observation of a dominating impact of the gene flow entering East Asia from the south in early human settlement, interpretation of the north–south division in this context poses the challenge to the field. Other areas of interest that have been studied include the gene flow between East Asia and its neighbouring regions (i.e. Central Asia, the Sub-continent, America and the Pacific Islands), the origin of Sino-Tibetan populations and expansion of the Chinese. ***

Genetic Markers and the Study Native Populations in East Asia

Mongoloid, Australoid and Negrito distribution of Asian peoples

Chinese researchers Feng Zhang, Bing Su, Ya-ping Zhang and Li Jin wrote in an article published by the Royal Society: Genetic markers are the tools in studying genetic variations. The most important genetic markers in human genetic diversity research (Du 2004) are: (I) blood groups that can be detected in red blood cells, including ABO, Rh and MNSs, (ii) human lymphocyte antigens and immunoglobulins, including Gm, kilometers and Am, (iii) isozyme markers, (iv) classic DNA polymorphisms using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and (v) contemporary DNA markers, including short tandem repeat (STR or microsatellite) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). However, it is the introduction of mtDNA and Y chromosome markers that has made a profound impact on our understanding of the genetic diversity of human populations (Wallace et al. 1999; Jobling & Tyler-Smith 2003; Pakendorf & Stoneking in press). ***

Zhao et al. (1987) and Zhao & Lee (1989) studied the Gm and kilometers alleles (or allotypes) in 74 Chinese populations and found that there is an obvious genetic distinction between the southern and northern Chinese. By analysing a comprehensive dataset comprising 38 classical markers, Du & Xiao (Du et al. 1997) validated the genetic differentiation of southern and northern Chinese and showed that they are separated approximately by the Yangtze River. Chu et al. (1998) showed that such a north–south division can also be observed in Chinese populations using DNA markers (i.e. microsatellites). This genetic division is also consistent with multidisciplinary evidence in archaeology, physical anthropology, linguistics and surname distribution (Du et al. 1991, 1992; Jin & Su 2000). Furthermore, the results from Chu et al. (1998) demonstrated that the north–south division is not limited to Chinese populations and is in fact a reflection of a north–south division of East Asian populations. In the last few years, genetic data on mtDNA and Y chromosomes have been accumulated at an unprecedented pace for East Asian populations. Again, a north–south division of East Asians was observed not only with Y chromosome markers (Su et al. 1999; Shi et al. 2005), but also with mtDNA data (Kivisild et al. 2002; Yao et al. 2002). These observations provided convincing evidence of a north–south division in East Asian populations. ***

However, this well-established fact was not accepted without being challenged. Karafet et al. (2001) did not observe the north–south division in East Asians using a set of Y chromosome markers that are less polymorphic in East Asian populations and that over-represent the lineages brought in by recent admixture. In a different study, Ding et al. (2000) examined mtDNA, Y chromosome and autosomal variations and failed to observe a major north–south division. The southern populations in their study (Ding et al. 2000) are primarily the Tibeto-Burman (TB) populations, which have a recent northern origin, and therefore would blur the north–south distinction (Shi et al. 2005). A more extensive study of mtDNA lineages provided a much higher resolution and consequently a strong north–south division emerged (Yao et al. 2002). ***

The north–south division raises the question of whether the southern and northern East Asians (NEAS) are descendants of the same ancestral population in East Asia or originated from different populations that arrived in East Asia via different routes. To date, three main hypotheses have been brought forward on the entry of modern humans into East Asia: (I) entry from Southeast Asia followed by northward migrations (Turner 1987; Ballinger et al. 1992; Chu et al. 1998; Su et al. 1999; Yao et al. 2002; Shi et al. 2005), (ii) entry from northern Asia followed by southward migrations (Nei & Roychoudhury 1993), and (iii) southern and NEAS are derived from different ancestral populations, i.e. southern populations from Southeast Asia and northern populations from Central Asia (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994; Xiao et al. 2000; Karafet et al. 2001). Therefore, to understand the mechanism of genesis and maintenance of the north–south division, much needs to be learnt about the origin and migration of the East Asians. ***

Jiahu Culture in China

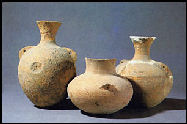

Vessels with the

oldest wine from China Jiahu is a rich but little known archeological site located near the village of Jiahu near the Yellow River in Henan Province in central China. About equidistant between Xian and Nanjing, the site was occupied from 9,000 to 7,800 years ago and then from 2,000 year ago to the present. In addition to yielding the oldest rice and wine and the earliest playable musical instruments, it may have also yielded the earliest examples of Chinese writing.

Jiahu villagers fished for carp; hunted crane, deer, hare, turtle and other animals; and collected a wide variety of wild herbs and vegetables such as acorns, chestnuts and broad beans and possibly wild rice. They also possessed domesticated dogs and pigs. Among the tools and utensils unearthed at Jiahu are three-legged cooking pots, arrows, barbed harpoons, stone axes, awls, and chisels.

Based on an examination of 238 skeletons Harvard forensic archeologist Barbara Li Smith concluded that the Jiahu villagers enjoyed fairly good health. The average age of death was around 40, late for Neolithic people. Sponge lesions on the skull indicate that anemia and iron deficiency were a problem. Hole bone lesions from disease and parasitic infections are rare.

Jiahu villagers practiced some unusual burial customs. In some graves the heads were severed from the body and pointed towards the northwest. Cut marks made when the bones were fresh indicates the heads were cut when the person was still alive or shortly after they died. Adults were generally buried whole in pits; juveniles were buried in pots. Most were buried in individual plots. Some were buried in groups up to six with a mix of sexes and ages.

See Separate Articles: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC CHINA factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000-5700 B.C.): CHINA’S EARLIEST CULTURE AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000 B.C. to 5700 B.C.) AND THE WORLD’S OLDEST WINE, FLUTES, WRITING, POTTERY AND ANIMAL SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; YANGSHAO CULTURE (5000 B.C. to 3000 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; HONGSHAN CULTURE AND OTHER NEOLITHIC CULTURES IN NORTHEAST CHINA factsanddetails.com; LONGSHAN AND DAWENKOU: THE MAIN NEOLTHIC CULTURES OF EASTERN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; KUAHUQIAO AND SHANGSHAN: THE OLDEST LOWER YANGTZE CULTURES AND THE SOURCE OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DOMESTICATED RICE factsanddetails.com; HEMUDU, LIANGZHU AND MAJIABANG: CHINA’S LOWER YANGTZE NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com

Jomon People in Japan

replica of Jomon-era clothes The period between 10,000 and 400 B.C. in Japan is referred to as the Jomon Period. The people who lived at this time are regarded as Japan's first major culture. Jomon is the name of the cord markings on the pottery found in this period.

Jomon people showed up at the end of the last ice age and appeared to have lived in isolation and had little contact with the people on the Asian mainland. Many scholars believe that the Jomon people were Ainu, a people who practiced a religion centered around blood-sacrifice and bear rituals and who survive today in small numbers in northern Japan.

The oldest Jomon Period remains were found in Chino in Nagano Prefecture. One of the largest Jomon sites is in Kasori, now part of Chiba city, near Tokyo. It boasts a large shell midden and was discovered by an American Edward Moss. It is now a preserved site with a constructed village open to tourists. There are several tunnels with glass walls that cut right into the shell midden. Places where prehistoric people live are often indicated by the presence of middens, heaps of discarded shells. Many have been found in the Tokyo area,

The Jomon people were hunter-gatherers who subsisted primarily on hunting animals like deer and boar, collecting acorns, nuts and fruits, and fishing and collecting mollusks in coastal waters. Their nomadic patterns revolved collecting fruits and nuts in the autumn and hunting and collecting shellfish in the spring.

Most Jomon people remained nomadic until around 5000 B.C., when they began settling in large, complex villages and building crudely-roofed houses, known as tate-ana jukyo (pit dwellings), supported by pillars built over shallow holes dug in the ground. Their settlements were particularly numerous along the sheltered bays on the Pacific Ocean side of Honshu. At that time climate was lightly warmer than it is today and the sea level was several meters higher than now. Many of the areas where these settlements occurred were along tidal flats.

One of their main sources of food was clams and other tidal mollusks. Archeologist have uncovered huge piles of discarded shells, known as middens, at Jomon sites. One midden was over 200 meters long. The Jomon people in these areas also hunted and fished — 6,000-year-old Jomon sites have yielded fish hooks, net sinkers, spears and dugout canoes — but the clams were a stable and reliable food source.

The Jomon people made fantastic designs on the edges of their pottery, wore large earrings and other jewelry, made a variety of ritual objects including phallic rods and ritual knives. Most impressive were their ritual clay figurines that possibly represented gods or were symbols of fertility. The Jomon possessed developed burial practices and views on life after death. One custom that endured in rural areas until fairly recently was placing the placenta and afterbirth of newborn children into a pot and burying at the entrance of a village.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; EARLIEST PEOPLE IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; STONE AGE (PALEOLITHIC) PEOPLE IN JAPAN: THEIR LIFESTYLE, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT factsanddetails.com; FIRST JAPANESE AND THEIR GENETIC HERITAGE factsanddetails.com; FIRST JAPANESE AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE AMERICAS factsanddetails.com; JOMON PERIOD (10,500–300 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; JOMON PEOPLE (10,500–300 B.C.): THEIR LIFESTYLE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; JOMON PEOPLE (10,500–300 B.C.): RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; JOMON FOOD factsanddetails.com; JOMON HOUSING AND VILLAGES factsanddetails.com; JOMON FISHING, PROTO-AGRICULTURE AND TRADE factsanddetails.com; JOMON CULTURE (10,500–300 B.C.): CLOTHING, MUSIC AND BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com; DOGU, STONE CIRCLES AND JOMON ART AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; AINU Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Genetic Origin of the Chinese

Genetic studies of 28 of China's 56 ethnic groups, published by the Chinese Human Genome Diversity Project in 2000, indicate that the first Chinese descended from Africans who migrated along the Indian Ocean and made their way to China via Southeast Asia.

DNA studies have shown that all Asians descend from two common lineages: 1) one more common in southern Asia, particularly among Vietnamese, Malays and New Guineans; and 2) one more common in northern Asia, particularly among Tibetans, Koreans and Siberians.

An exhaustive analysis of the genes of 8,200 ethnic Chinese has revealed subtle genetic difference in Chinese that live in northern China and those that live in southern China. A study by Liu Jianjun of the Science, Technology and Research Agency of Singapore, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics in 2009, revealed variants between the two groups that are somewhat consistent with those of historical migrations to the two regions.

In December 2009 Lui told Reuter, “This genetic map...tells us how people differ from each other, or how people are more closely linked to each other...We don't know what these variants are responsible for. Some have clinical outcomes and influence disease development. This is what we are interested in genetic variation." The scientist also found genetic difference between Chinese dialect groups. Liu told Reuters, “Different dialect groups are definitely not identical...language is a reflection of our evolution, that's why you see the differences."

See Separate Article: GENETIC ORIGIN OF THE CHINESE AND THEIR LINKS TO TIBETANS, TURKS, MONGOLS AND AMERICANS factsanddetails.com

Horsemen

Pazyrik Horseman

The Mongols, Turks, Huns, Tartars and Scythians are the best known of horsemen groups that have roamed the steppes of Central Asia and the ones that were most successful expanding beyond their native realm and impacted the worlds they touched. The Mongols created the largest empire the world have ever known. The Huns sacked Rome and forced European to build castles for protection. The Turks drove the last Christians empire out of the Middle East and came close to Islamicizing Europe.

Horseman groups originated about 2,500 years ago and continue in various forms today. Throughout their long run they have maintained many of the customs, characteristics, martial arts and methods of organization that evolved millennia ago such spending living in yurt-style tents, drinking fermented mare's milk, fighting from horseback and creating art forms that celebrate horses and animals of the steppe.

Horse riding's origins are uncertain and could date to at least 4,000 years ago, archaeologist Margarita Gleba of University College London told Science News. Victor Mair, a China and Central Asian expert at the University of Pennsylvania, suspects that horse riding began about 3,400 years ago in wetter regions to the north and west of the Tarim Basin in western China. [Source: Bruce Bower, Science News, May 30, 2014]

First Horsemen

The first domesticated horses appeared around 6000 to 5000 years ago. The first horseback riders may have been people from the Sredni Stog culture, who lived east of the Dnieper River, in what is now Ukraine, between 4200 and 3500 B.C. Evidence for this claim are scraps of bone and horn that may have been the cheek pieces of bridles. Archeologist David Anthony of Hartwick College in New York have examined horse teeth found at Sredni Stog sites, looking for signs of wear from metal or rope bits. [National Geographic Geographica, June 1989].

The first hard evidence of mounted riders dates to about 1350 B.C. Uncovering information about ancient horsemen is difficult. They left behind no written records and relatively few other groups wrote about them. For the most part they were nomads who had few possession, and never stayed in one place for long, making it difficult for archeologists — who have traditionally excavated ancient cities and settlements of settled people — to dig up artifacts connected with them.

For similar reasons it is difficult to work out how different horsemen groups interacted and how individuals within the group behaved. What little is known about group interaction has been learned mostly from the work of linguists. Most of what is known about their behavior is based on observations of modern groups or a hand full of descriptions by ancient historians..

Based on these sources, scholars believe that early nomadic horsemen lived in small groups, often organized by clan or tribe, and generally avoided forming large groups. Small groups have more mobility and flexibility to move to new pastures and water sources. Large groups are much more unwieldy and more likely to generate feuds and other internal problems. On the steppe there generally was enough land for all so the only time horsemen needed to unite was to face a common threat.

Botai Horsemen

Murong horseman

Some archeologist believe that horses were first domesticated by the Botai, a group of people that dressed in marmot furs with the feet still attached and lived in pit houses half dug into the ground in northern Kazakhstan about 6,000 years ago. Excavations from a site called Krasny Yar indicate that people were quite fond of horsemeat. Around 90 percent of the bones found in their homes were from horses.

Many archeologist believe the Botai simply hunted all these horses. Archeologist Sandra Olsen disagrees. She argues the horses were herded, and thus domesticated, and may have been ridden. Her evidence is largely circumstantial. She has noted for example that there are roughly equal numbers of male horse bones and female horse bones founded at Bontai sites. Hunter sites have mostly female bones because females are easier to hunt.

More persuasive is her argument based on the fact that large numbers of full skeletons were found at the Botai sites. She reasoned the horses were herded to the site and slaughtered. Wild horses killed out on the steppe have to be chopped up in pieces to transported back to the site. She has also founded wear and tear on the jawbones similar to that founded on horses who use bridles.

In 2009, scientists announced that pastoral people on the Kazakh steppes appear to have been the first to domesticate, bridle and perhaps ride horses — around 3500 B.C., a millennium earlier than previously thought. The discovery was made near a settlement called Botai in northern Kazakhstan, where the steppes of Central Asia begin to give way to the forests of Siberia. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “Evidence for the earlier date for equine domestication is described in the journal Science by an international team of archaeologists. The report's lead author is Alan K. Outram of the University of Exeter in England. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, March 5, 2009 +++]

“The archaeologists wrote of uncovering ample horse bones and artifacts from which they derived “three independent lines of evidence demonstrating domestication” of horses by the semi-sedentary Botai culture, which occupied sites in northern Kazakhstan for six centuries, beginning around 3600 B.C. The shape and size of the skeletons from four sites was analyzed and compared with bones of wild horses in the region from the same time, with domestic horses from centuries later in the Bronze Age and with Mongolian domestic horses. The researchers said the Botai animals were “appreciably more slender” than robust wild horses and more similar to domestic horses. +++

“Dr. Outram said in an interview that it was not clear from the research if the breeding of the tamed Botai horses had by then led to the origin of a genetically distinct new species. But their physical attributes were strikingly different, he added, and this made the animals more useful to the people as meat, sources of milk and beasts of burden and locomotion. The second pieces of evidence were the marks on the horses’ teeth and damage to skeletal tissue in the mouths. The researchers said this was caused by the wearing of mouthpieces, bits, inserted for harnessing with a bridle or similar restraint to control working animals." +++

“Other archaeologists, digging at other sites, have detected similar traces of what they said was bit wear, but this has been disputed as support for domestication. Dr. Outram said that some of the damage to the Botai teeth and jawbones could have been caused only by bit wear. Botai pottery yielded the third strand of evidence. Embedded in the clay pots were residues of carcass fat and fatty acids that “very likely” came from mare's milk, the researchers said. This “confirms that at least some of the mares of Botai were domesticated," they concluded." +++

Early People from Russia and Siberia

The oldest of the far northern people of Eurasia were Neolithic hunters of wild reindeer. Archeological evidence of their existence has been dated to the 5th milleneum B.C.. Small scale reindeer herding is believed to have evolved around 2,000 years ago with large scale herding developing in the lasted 400 years.

The earliest known Siberians were early stone age tribes that lived around Lake Baikal and the headwaters of the Ob and Yenisey rivers. Later stone age sites have been found all over Siberia. Many tribes were still in the stone age when they were discovered by Russians. When the Greeks dominated Europe, Siberia was inhabited largely tribes that originated in the Caucasus. After the 3rd century B.C. it was occupied by a secession of horsemen—Huns, Turkic tribes and Mongols.

The earliest inhabitants of the tundra and the taiga are believed to Mongolian-descended hunters and reindeer herders. Little is known about them because they had no written language and left behind few artifacts. A 5,000 year-old Siberian rock engraving shows a stone-age man on skis trying to have sex with an elk.

Many Siberian groups used tepees and had religious beliefs similar to those of native Americans. Many scientists believe they may be related to the first people to cross the Bering Strait even though soe of these groups lived more 2,000 kilometers from the Bering Strait. The spear points found at the Yana River site in Siberia resemble those of the Clovis People, who lived in North America at least 12,000 years ago.

In the April 2008 issue of Science, University of Oregon professor Dennis Jenkins said that he found some fossilized pieces of excrement in the Oregon dated to be 14,300 years old. Using a new technique called polymerase chain reaction — which allows researchers to “unzip” minute fragments of DNA and make millions of duplicate so they can be tested — he was able to determine the excrement was human and was linked genetically to native Americans and Asians.

Early Aboriginals in Australia

Little is known about the earliest inhabitants of Australia. They migrated from Asia in numerous waves and are categorized into two distinct groups: "Robust" and "Gracile." Robust people are believed to have arrived first. Aboriginals are believed to have descended from Gracile people.

The earliest inhabitants of Australia may have been the descendant s of Negrito tribes that live today in Malaysia, the Philippines and some Indian Ocean islands. Some anthropologists believe they are descendant of wandering people that "formed an ancient human bridge between Africa and Australia.”

People were living in the Lake Mungo area, near Melbourne, 38,000 years ago. The skulls of these people had thick walls ("Robust"), while those found elsewhere are thin ("Gracile"). This finding has led scientists to believe there may have been two migrations of people to Australia.≤

By 35,000 years ago, people had spread throughout Australia, as well as Tasmania and New Guinea, both of which were connected to Australia by land bridges. One of the oldest sites in Tasmania, Parmerpar Meethaner, was occupied beginning around 34,000 years ago.

Around 13,000 to 11,000 years ago the last land bridges disappeared and cultures in Tasmania and New Guinea became isolated from those on the Australian mainland. More advanced "microlthic" stone-tool technology appeared on the mainland between 4,000 and 3,000 years ago but never spread to Tasmania. Neither did the dingo, a dog introduced from Southeast Asia about the same time.

Aboriginal painting

Early Aboriginal Lifestyle

The early Aboriginals were hunters and gatherers. They did not farm or build permanent settlement. They didn't use the wheel. Many, it is believed, wandered around barefoot and completely naked. They lived in lean-tos and cooked over open fires. Tools included tertiary-tipped stone tools, grove-edged axes, and boomerangs (the ancient Egyptians also used boomerangs).

Early Aboriginals set bush fires to flush game for hunting. In the process they encouraged the growth of new shoots, the food fancied most by animals. They also gathered witchetty grubs from overturned logs, impaled gouanas, and hunted wombats and kangaroos. Early Aboriginals living on the coast ate a lot of mollusk. Evidence of this are huge piles of shells.

Aboriginals made most of their tools and dwelling from plant material, and thus most of the remains rotted away thousands of years ago. Most Aboriginal archaeological sites reveal stones tools and fireplaces and little else. A necklace made from kangaroos teeth was unearthed from a 12,000-year-old tomb in Kow swamp in northern Victoria. A necklace made from Tasmanian devil teeth was unearthed from a 6,500-year-old tomb at Lake Nitchie in western New South Wales.

The distribution of major archaeological sites all over Australia indicates how widely dispersed the early Aboriginals were. They include Malanangerr, a rock shelter in Arhem Land in Northern Territory; Mirium, a rock shelter on the Ord River in Kimberley in Western Australia; Mt. Newman in the Pilbara region of in Western Australia; the Devil's Lair, near Cape Leeuwin in southwest Australia; Koonalda Cave in the Nullarbor Plains of South Australia; Mootwingee National Park in New South Wales; and the Early Man Shelter near Laura in northern Queensland.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Jwalapurum, Researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018