AINU

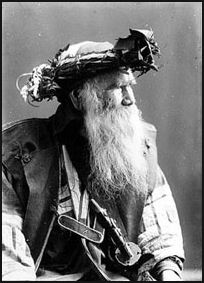

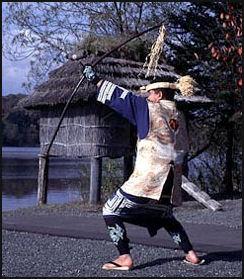

Ainu man in the

early 20th century The Ainu are an ethnic group, distinct from the Japanese, that live today almost exclusively on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. They were traditionally hunters-gatherers and fishermen. They didn't practice rice farming like the Japanese. They hunted bear, sea otter, deer and other animals, gathered wild plants and fished for whales, seal lions, swordfish and salmon on the open seas until they were driven inland by the Japanese.

The Ainu traditionally were not a homogeneous group and were usually divided into three groups: 1) the Kurile Ainu, who lived on the Kurile Islands in present-day eastern Russia; 2) Sakhalin Ainu, who lived on the northern Sakhalin Island in present-day eastern Russia; and 3) Hokkaido Ainu, who lived on Hokkaido and southern Sakhalin Island. "Ainu" (pronounced EYE-noo) is the Ainu word for "human.” The Ainu have rounder eyes, ighter skin and more body hair than the Japanese.

The Ainu are quickly vanishing as a distinct and separate group of people. There are only a few hundred pure-blooded Ainu left. Government surveys counted 23,782 pure- and mixed-blood Ainu in Hokkaido in 2006 and several thousand in Tokyo and about a thousand in other places in Japan.. Most live in the Hidaka district of Hokkaido, southeast of Sapporo. An Ainu cultural organization said the true number of Ainu could actually be higher because many Ainu do not admit their ethnic background to avoid discrimination.

Good Websites and Sources: Ainu Museum ainu-museum.or.jp ; Smithsonian Site mnh.si.edu/arctic ; Literatures and Materials of Ainus Language jinbunweb.sgu.ac.j ; Wikipedia article on the Ainu Wikipedia ; Ainu Association of Hokkaido ainu-assn.or ; Ainu-North American Similarities molli.org.uk/explorers ; Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture frpac.or.jp ; Boone Collection of Ainu Images and Artifacts fieldmuseum.org/research_collections ; Ainu Language and Japan’s Ancient History List of Resources /www.dai3gen.net ; 18th and 19th Centuries Ainu Documents digicoll.library.wisc.edu ; National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka minpaku.ac.jp ; Links in this Website: FIRST JAPANESE Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Ainu Tourist Sites Ainu Village (on the shore of Lake Poroto in Shiraoi in Hokkaido) features houses constructed in traditional Ainu style. Traditional Ainu dances and demonstrations of traditional embroidery and weaving are demonstrated at the handicrafts house. Ainu Museum (within Ainu Village) is one the best places to catch a glimpse of Ainu culture. It has an excellent displays of precious heirlooms and utensils and sells a catalogue put together by the Shiraoi Institute for the Preservation of Ainu Culture, Wakakusa 2-3-4, Shiraoi, Sapporo Pirka Kotan welcome.city.sapporo

Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993). Contacts: Hokkaido University’s Center for Ainu & Indigenous Studies; the Ainu Association of Hokkaido (formally known as Hokkaido Utai Association) ; Shiraoi Institute for the Preservation of Ainu Culture, Wakakusa 2-3-4, Shiraoi, Hokkaido; Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (FRPAC), Ainu Culture Center, ☎ (03)-3245-9831.

Origin of the Ainu

The origin of the Ainu is a mystery. Genetically they more similar to dark-skinned groups found in Southeast Asia than the Japanese or Koreans.

In Japanese history the period between 10,000 and 400 B.C. is known as the Jomon Period. The people who lived at this time are regarded as Japan's first major culture. Many scholars believe that the Jomon people were Ainu or at least that the Ainu descended from the Jomon People.

The skull and facial structures of the Jomon people and the Ainu are similar to each other. DNA samples taken from ancient burials also indicates that the Jomon people were similar genetically to the Ainu but very different from modern Japanese. Similar analysis shows that modern Japanese are similar genetically to modern Chinese and Koreans. This suggests that modern Japanese evolved from Chinese and Koreans not Jomon people who are more closely linked to the Ainu.

Archaeologists have found Japanese-style pottery fragments on Vanuatu (a Pacific island east of Papua New Guinea and 6,000 miles south of Japan) dated to 3000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that maybe some ancient Jomon period fishermen were carried south by ocean currents. The pottery could have also arrived there through trade, via the Philippines or Borneo perhaps.

Early History of the Ainu

In the Stone Age, some scholars believe that most of the people living on the four main islands of Japan were Ainu. By the A.D. 10th century they also inhabited Sakhalin and the Kuril islands and had contacts with the Chinese and Mongols and other tribes in what is now China and eastern Russia. Some even had contacts with Aleuts that lived around the Bering Sea.

The Ainu initially inhabited much of northern Honshu as well as Hokkaido and islands that are now part of Russia. For many centuries the Japanese and Ainu lived in peace and intermarried. The Ainu traded furs for sake, pottery and hunting implements with the Japanese and also traded with the Chinese, Tungus (a Siberian tribe) and the Russians. One thing that affected fate of the Ainu was they fact the lived between the expanding Russian and Japanese empires. That meant that the Japanese and Russians took more of an interest in Ainu land than they might otherwise have had.

Over the centuries the Ainu in Japan were driven northward and defeated in battles by the Japanese. The Japanese conquest of the Ainu was slow, gradual and not always deliberate. The Ainu periodically rose up in revolt. In the 9th century, Imperial Japan extended into northern Honshu by defeating the Ainu. The Ainu made their last stand in Honshu in 1669 outside Fukuyama castle, where they were mowed down by superior Japanese steel and firepower. Like other indigenous people around the world, they were also devastated by smallpox and other diseases they were exposed to and to which they had little resistance.

By the 18th century, the Ainu were largely confined to Hokkaido. Many intermarried with and let their traditions die. By the end of the 19th century large numbers of Japanese began moving into Hokkaido with little resistance from the Ainu. The Ainu were encouraged to give up hunting and were forced to move to land suitable for agriculture.

Ainu and Japanese

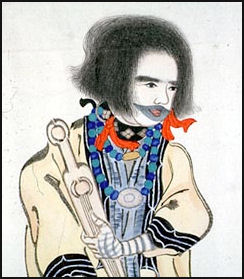

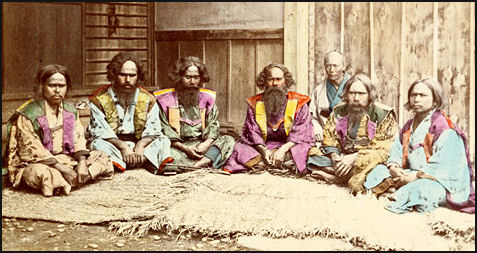

19th century Japanese

depiction of the Ainu The way the Ainu have been treated by the Japanese government is not all that different the way native Americans have been treated by the U.S. government. Both were forced to move from their ancestral lands and pressured to assimilate.

Most of what is known about the Ainu’s past comes from Japanese historians and Western anthropologists. One of the earliest reference to the Ainus was a description of "hairy people" living in northern Japan. Much of what has been gleaned about them before the 19th century comes from “Ainu-e”, a genre of Japanese illustrations of Ainu life with detailed notes written in the margins. When Japan adopted the Family Registry Law in 1871, Ainu were placed in a separate category of “commoners.” Certain practices such as their hunting practices and the Iomante bear festival — were banned or restricted.

The Former Aborigine Protection Law, enacted in 1899, forced the Ainu to assimilate with the Japanese and curbed expressions of Ainu cultural identity. Ainu were forbidden from using their native language and were forced to take Japanese names. They were given plots of land but banned from transferring them except through inheritance. The land they were given for the most part was land that Japanese settlers didn’t want. Much of it was unsuitable for growing crops. A new law in 1997 gave the Ainu official status as Japan's original inhabitants, recognized their language and culture and gave them the legal right to be different.

Since the 19th century, the Ainu have been one of Hokkaido's biggest tourist attractions. They have often been displayed in humiliated shows the way native Americans were in the old Wild West shows.

As of 2009, the central government’s dealings with the Ainu was handled by several different offices in different miniseries. Experts have called for these offices to be unified into a single body and have sort of centralized oversight.

Ainu in Japan Today

Few remaining Ainu speak their traditional language, practice their traditional religion and old customs any longer. In recent years, there has even a renewed interest in Ainu customs by both Ainu and non-Ainu. In 1999, there was major exhibition of Ainu art and culture at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C.

Most Ainu speak Japanese. Only a few speak the old Ainu languages, which were unlike any other. Many make a living being displayed at Disneyesque "Ainu Villages" on Hokkaido, where they unenthusiastically act out old festival ceremonies and shaman rituals.

About 5,000 Ainu live in the Tokyo area. Among those active in trying to keep Ainu culture alive are Mina Sakai, who leads an entertainments group called “Ainu Rebels” that performs traditional dances and music with a modern twist. Rera no Kai (Rera Meeting) is a group of Ainu living in the suburbs of Tokyo that are dedicated to keeping traditional Ainu performing arts, culture and cooking alive.

Ainus still face discrimination. Ainu children that attend Japanese schools are often bullied and called Inu (Japanese for "dog"). About 3.8 percent of Ainu are on welfare, 1.3 points higher than the national average and only 17.4 percent of Ainus received a university education, compared to the national average of 38.5 percent.

Ainu continue to live underprivileged lives. According to a October 2008 survey by Hokkaido University’s Center for Ainu & Indigenous Studies and the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, the average household income of Ainu was $35,600, 40 percent below Japan’s national average, and only 20.2 percent of Ainu went to college, less than half the national rate of 42.2 percent.

In the survey 33.5 percent of the respondents said they considered themselves impoverished and 40.5 percent said they had trouble making a living. Among Ainu households, 5.2 percent received welfare, compared to the national average of 2.1 percent, and 4.8 percent did do in the past.

Seventy percent pf Ainu attended high school. Of those 10 percent dropped out. The university drop out rate was 19.1 percent. Over 75 percent of those who abandoned plans to finish higher education did so out financial concerns.

Ainu Physical Characteristics

Ainu have light skin, lots of facial and body hair, round eyes, wavy hair and large bodies. Unlike most Japanese men, Ainu men can grow thick, wiry beards. The first Western anthropologists who encountered them theorized the Ainu might have descended from Europeans, a theory that has since been discredited.

Some people insist that Ainu don’t really look that much different from Japanese. It is difficult to tell because most modern Ainu have at least some Japanese blood in them. According to one estimate there are probably less than 200 pure-blood Ainu left.

Some anthropologist regard the Ainus as a collection of different ethnic groups rather than one single ethnic group that spoke different languages and had different cultures.

Ainu Language and Religion

The Ainu didn't have a written language. Different Ainu dialects were often quite different from one another. Some Ainu believe that many words in their language are derived from terms that originally described sexual acts. The Ainu word for man, “onoko”, consist of three separate words “o”, “no” and “ko” which refer to male and female sexual organs.

Many places in Hokkaido--such as Sapporo and Shiretoko--take their names from the language of the Ainu. Additionally, Japanese words such as “ tonakai “ (reindeer) and “ rakko “ (sea otter), also trace their origins to the Ainu language.

Religion was one thing that bound the diverse Ainu groups together. Religion and life were intermixed. Even things like throwing away bones had religious significance because of their association with spirits. The Ainu believe in three main kinds of spiritual beings: 1) deities; 2) spirits of the dead; and 3) evil spirts called “oyasi or wenkamuy”, which are often associated with disease and sometimes are unhappy spirits of the dead.

The Ainus have traditionally believed that the earthly things that sustained them — hunting, knives, bamboo houses and the animals and plants they ate — were gods in disguise, spirits temporarily visiting the world of man.

Ainu deities (“kamuy”) are not all that different from Japanese “kamis” (spirits). The Ainus believe that everything in the physical world — mountains, trees, lakes and animals — are inhabited by spirits and they must be treated with respect. They regard the deities of animals as having the same powers as those associated with humans and regard them as whimsical creatures that can bring good fortune or bad depending on their whims. The most important deities are linked with mountains, fire, houses, the sun, the moon, water, forests, bears, foxes, owls, seals and other animals. The Ainu worshiped flying squirrels as protector gods of children.

The Ainu believe that most beings in the Ainu uiverse possess a soul that can leave a person’s body and experience things in places the person has never been. Similarly, the souls of the dead can travel to the world of the living. The Ainu have elaborate funeral rituals for people and a wide range of animals. They believe that dead bodies should be treated with respect so that soul feels properly treated and thus will not come back and haunt the living and bring disease and other problems. Unlike deities who act on their whims, the spirits of the dead can be placated.

Even Ainus living in Tokyo keep alive traditions related to their respect for Kamuy (God). A Japanese woman named Makiko Ui who spent 18 years with urban Ainu told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “When someone spills water on the table, for example, other people say: “Kamuy wanted drink water there,” rather than, “What’s wrong with you?”

Ainu Rituals

The Ainu have traditionally practiced a religion centered around blood-sacrifice and bear rituals. The rituals were traditionally carried out by shaman who carried sacred sticks. Ainu rituals that are still practiced often have Japanese elements such as offerings of rice, sake and swords.

As an expression of thanks for filling the world with life, the Ainu ritually sacrificed animals such as owls, foxes and bears during important occasions to send their spirits back to the spiritual worlds. In contrast, the Japanese show their thanks to the spirits by offering gifts.

Ainu shaman are believed to have the power to travel to the world of the dead and bring back spirits to the world of the living. They have usually been men but sometimes have been women. They have traditionally held high status and have been called upon to cure ailments by going into a trance and calling on certain spirits that can help with a particular ailment.

Ainu Bear Rituals

The Ainu had great reverence for bears, Bears were providers of food, fur and bone for tools. They hunted them, kept them as pets, and performed exorcisms involving bear spirits. Sometimes bear cubs were caught and nursed by women. The bear supplied fur and meat and brought gifts from the deities and was regarded as the important mountain god in disguise.

The most important Ainu rite was the “iyomante”, or the bear sending ritual. Conducted in the spring, it was essentially a funeral ritual for the most important Ainu deity and was intended to give the bear and mountain god spirit a proper send off before it returned to the mountains. A female bear and her cubs were caught. The bear was killed and her spirit was sent to the gods in a special ceremony. Her cubs were then raised by the Ainu for several years and they too were returned to the gods.

During the ceremony people donned their best clothes and there was a lot of drinking, dancing and feasting. Prayers were said to the fire, house and mountain gods. The bear was taken from the bear house and killed with arrows and by strangling it between logs. The bear was then skinned and dressed and placed before an altar hung with treasures and then placed through a sacred window. The ceremony ended when the head of the bear was placed on the altar and arrows are fired to the east so its spirit could return to the mountains. Among some Ainus a male bear was killed and its penis, head and other body parts were taken to a sacred place on the mountains. The four-day-long ceremony was supposed to send the bear back to the mountains gods as an honored messenger of the village.

Without guns the Ainu killed bears used bamboo arrows poisoned with a preparation made from the roots of a small purple-flowered plant called are “ Aconitum yesoense “ . Hunters tested the potency of the poison by placing a tiny bit on their tongue or between their fingers. If there was a burning sensation it was strong enough. When struck by a poisoned arrow the bear ran 50 to 100 meters and collapsed as a result of the fast-acting poison. [Source: the book “Bears of the World” by Terry Domico]

Bears that were ritually killed and eaten were bears captured as cubs that were usually raised for about two years in the local community. The cub was raised by village women who often took turns nursing them with their own breasts. Noako Maeda, curator at the Noboribersu Bear Park, has studied the Ainu and bears and suckled bear cubs with her breasts. She told the writer Terry Domico they nurse very gently, more gently than her own children.

The ceremony was presided over by the community leader. Even though iyomante was prohibited by the Japanese it was practiced into the 20th century. The Japanese government formally forbade the Ainu bear festival in the early 1960s. Today, watered-down versions of the festivals are sometimes performed for tourists. The Ainu continue to worship and revere bears but they no longer ritually kill them.

Ainu Life

Today the Ainu live in homes similar to other Japanese. In the old days they migrated between summer camps set up along the coast and winter settlements further inland, often along rivers. The inland houses were semi-underground pit houses. The settlements tended to be small, with no more than five ro six families.

Nuclear families were more important than extended families. Rights to hunting grounds was passed down through male relatives. Some groups practiced polygamy. As a rule they was rarely any social or political group larger than the settlement groups. Major decision were traditionally made elders by within the settlement group.

In the old days, Ainu divided their land into “iwor”, village gathering grounds where they fished for salmon, hunted bear and gathered wood and berries.

Ainu men traditionally fished for trout and salmon with nets, traps and weirs and hunted bear and deer with bow and arrow, spears and traps while the women collected plants. Dogs were used for hunting and sometimes fishing. Spear points and arrow heads were often tipped with stingray poison or a poison made from purple flowersto ensure that wounded animals didn’t run away too far.

The Ainu used large dugout canoes that were about 10 meters long and 80 centimeters wide made from large logs. They took to the rough seas off Hokkaido in these canoes, which were usually not seaworthy in their own right. It is believed that the Ainu lashed two dugouts together to make a primitive sort of catamaran.

Traditional foods included salmon, ezoshika deer, and wild plants and grasses. Dishes served at Ainu restaurants include venison, toasted smoked salmon with mountain vegetables; ezoshika deer with garlic, apple and other ingredients, thinly-sliced frozen salmon, potato starch dumplings, salmon and vegetable soup, and gyoja-nunniku, a plant native to Hokkaido that can be boiled, grilled, rolled in meat or prepared with egg and rice or added to soup. Gyoja-nunniku has a smell that is as strong as garlic and it is believed to keep evil away.

Ainu Clothes and Tattoos

Ainu men often had long beards. Women today who dress in traditional clothes wear fez-like hats and black robes with bold, white, swirling patterns. In the old days they wore kimono-like robes made brown of elm-bark fiber and capes and boots made from embroidered salmon skin.

In the old days, Ainu women had black tattoos, resembling clown smiles, around their lips. Their primarily purpose was to help unmarried women to attract husbands and were regarded as a sign of virtue. The practice was banned the Japanese government around the beginning of the 19th century but endured well into the 20th century. Some women also had tattoos on their hands. [Source: Sister Marry Inez Hilger, National Geographic, February 1967]

These tattoos were made by injecting cooking ash into small knife cuts made around the women's lips. The first cuts were made in a small semicircle on a girl's upper lip when she was only two or three years of age and a few incisions were added every year until she was married.

The Ainu freely assimilated products and ideas from other cultures. Atsuko Matsumoto wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “A good example of this is the kaparamip, a ceremonial dress. Traditional Ainu dresses were usually made with fabric woven from the bark of indigenous trees, such as ohyonire and nettle, as they did not produce cotton or silk garments. But this kaparamip is decorated with pieces of printed cotton material on the collar and around the cuff of each sleeve, while covered with a large piece of white cotton cloth cut out along a geometric Ainu pattern traditionally passed down from mother to daughter, making each design distinctive.” [Source: Atsuko Matsumoto, Daily Yomiuri, October 22, 2010]

"A large piece of white cotton material and a piece of cloth with a printed pattern were both obtained from the wajin and were used as appliques on the dress. This kind of attire only began to appear during the Meiji era [1868-1912] because it was only at around that time such white cotton fabrics became available at a reasonable cost to many Ainu people," Takahashi said. The term "wajin" is generally used to distinguish the ethnically Japanese majority from the Ainu people. "The Ainu people also traded with ethnic minorities in China and Russia. They adopted many ideas and items into their traditional styles to create unique blends," the curator explained.

Ainu Arts and Culture

Most Ainuart and crafts were made of wood and other perishable materials. As a result there are few old works of art and archeological artifacts. A group of contemporary Ainu artists and sculptors is very active today.

On the Ainu concept of beauty. Noriko Takahashi, a curator at the Kawasaki museum, that had exhibition of Ainu art, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “They use patterns and carvings to decorate a variety of everyday items they use,” focusing on “patterns, colors and carving techniques...so almost everything... are adorned with some sort of pattern." Korekiyo Sugiyama, of the Kyobashi gallery in Tokyo, which often features Ainu art, told The Daily Yomiuri, Ainu “craft pieces express the Ainu people's concept of nature and how they're engaged with animals and gods.”

Ainu produced carvings, weaving and embroidery of great beauty. Traditionally, these activities have been associated more with everyday life than special ceremonies. For ceremonies, the most important objects were often swords and lacquerware obtained from the Japanese.

The Ainu have a long tradition of “yukar” (epic poems), folktales and songs that served as literature, tributes to the deities, and sources of knowledge, history and moral codes. The epic poems were chanted by narrator-singers. The longest ones were 150,000 verses. Because there has been no written language, their literature has traditionally been handed down orally from one generation to the next. Because, many young Ainu are not interested in the old traditions there is a chance this literature could be lost except for what has been recorded by anthropologists.

Ainu dance in a clockwise fashion. Some Ainu still do the “hararaki”, crane dance. The dance mimics the crane. The traditional bow dance is known as the “ku rimse”. Ainu traditional dance was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2009. In the old days, Ainu women greeted each other by making a whining, crying noise. The mukkuri is an Ainu musical instrument similar to a Jew’s harp. Some songs are about the deeds of ancestral heros.

Oki Dub Ainu Band mixes traditional Ainu music with Western rhythms.

“Ainu” Carved Wooden Bears

Woodcarvings of bears are found at almost every souvenir shop in Hokkaido. The come in a variety of styles of styles--including the ubiquitous wooden sculpture of a bear carrying a salmon in its mouth. They are often said to be of Ainu origin but in fact they were inspired by carved bears from Switzerland. Atsuko Matsumoto wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Some of the woodcarvings were purchased in Switzerland by Tokugawa Yoshichika (1886-1976), when he and his wife traveled around Europe in 1921 and 1922... Impressed with the Swiss crafts, which were already common as peasant art in Europe, Yoshichika brought them back to Japan and introduced them to settlers in the Yakumo region of Hokkaido. [Source: Atsuko Matsumoto, Daily Yomiuri, October 22, 2010]

Museum curator Takahashi said, "Yoshichika showed the Swiss-made bear carvings to workers at the farm, suggesting they should make something similar. The production spread because the necessary carving techniques matched those of the Ainu. These carvings, initially introduced as products for industry during the agricultural off-season of winter, began to be produced by the Ainu as Hokkaido souvenirs.

Ainu Activism

In 1997, a court acknowledged for the first time the existence and cultural rights of the Ainu and the Law for the Promotion of Ainu Culture replaced the 1899 Hokkaido Former Aborigine Protection Laws which had called for the Ainu to assimilate and was considered the principal source of discrimination against the Ainu. The new law also set up the central- and Hokkaido-government-funded Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture.

Koichi Kaizama, an Ainu activist in Hokkaido, has sued the government over the construction of the Nibutani Dam, which was build in 1986 in Ainu spiritual grounds. Even though a court ruled the dam was illegal the claim to return the land and tear down the dam was rejected. The dam only provides electricity for 1,000 people and has been limited in preventing flooding.

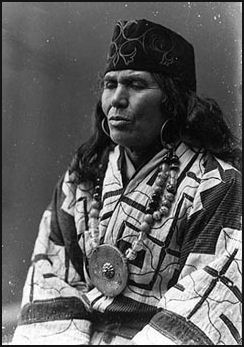

19th century photo of the Ainu

Ainu activist Shigeru Kayano (1926-2006) was the first Ainu to serve as a member of the Diet.

In June 2008, the Ainu were officially designated as “indigenous people” for the first time by legislation passed unanimously by both houses of Japanese legislature. An effort to make designation was inspired in part by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted in September 2007. It is not clear what the designation means. Some Ainu want the return of their traditional lands and certain hunting and fishing rights.

In February 2012, The Ainu Party of Japan was launched in Ebetsu City, Ainu Mosir (Hokkaido), marking a historical moment for Japan. This is the first time an ethnic minority group has ever created a political party of its own in Japan. The day of the launch commenced with an Ainu ceremony held outside the snow-covered Ebestu City Community Center. Members of the Maori Party in New Zealand were among those present.

Image Sources: Ainu Museum in Hokkaido, British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013