AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFARENSIS

Lucy and Child Australopithecus afarensis is one of the oldest know hominin species. Thought to have been primarily a vegetarian, possibly a scavenger, it lived in dry uplands and around wooded lake shores. Australopithecus afarensis (meaning “southern Ape from Afar”) possessed a combination of ape-like and human-like traits. Slender and small-brained, it had large, prominent teeth and walked upright, but had long, strong arms and curved fingers, making it adept for life in the trees. No direct evidence of tool making has been found but tools dated to the period in which lived have been found near A. afarensis fossil sites.

"Lucy" is the most famous example of Australopithecus afarensis. One of the surprising things about A. afarensis is that it was a surprisingly durable creature, surviving for nearly 900,000 years unchanged, between 3.9 and 3 million years ago. In contrast modern man has only been around for 100,000 to 200,000 years and Neanderthals existed for about 300,000 years. A. afarensis is believed to have evolved into other Australopithecus species which eventually died out. Some scientists believe it evolved into other hominin species after a long period with a dryer, cooler climate. These hominins in turn developed into “ Homo” species. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times]

Geologic Age About 3.9 million to 3 million years. Size: males: 1.5 meters (4 feet 11 inches), 45 kilograms (99 pounds). females: 1.1 meters (3 feet 5 inches) tall, 29 kilograms (64 pounds). Males are about the same size as pygmy men in Central Africa. Brain Size: 400 to 500 cubic centimeters. One third the size of a human brain (1,350 cubic centimeters) and about the same size as a chimp brain (390 cubic centimeters). Perhaps same intelligence of an ape. Linkage to Modern Man: Skeletal features indicate she was on the line that lead to the human genus, Homo. Nickname: Lucy.

Discovery Sites: The fossils of more than 300 A. afarensis individuals have been found so researchers know quite a lot about Lucy and her relatives.Lucy was discovered near Hadar, Ethiopia. The skeleton is housed at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa. Remains of 60 “A afarenis” individuals have been discovered at Laetoli, Tanzania. Remains have also been found in the Aramis and Omo areas in Ethiopia and Lake Turkana in Kenya.

See Separate Articles: AUSTRALOPITHECINES: CHARACTERISTICS, POSSIBLE TOOL USE AND DIVERSITY factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AND EARLY HOMININ FOOD, DIET AND EATING HABITS factsanddetails.com ; LAETOLI FOOTPRINTS factsanddetails.com; DIFFERENT AUSTRALOPITHECUS SPECIES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFRICANUS: TAUNG CHILD, LITTLE FOOT AND MRS. PLES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA: DISCOVERY SITE AND SIGNIFICANCE factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; PARANTHROPUS AND KENYANTHROPUS (ALSO CLASSIFIED AS AUSTRALOPITHECINES) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Lucy: the Beginnings of Humankind” by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey (1981) Amazon.com;

“Lucy's Legacy: The Quest for Human Origins” by Dr Donald Johanson and Kate Wong (2009) Amazon.com;

The Paleobiology of Australopithecus (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by

Kaye E. Reed, John G Fleagle, Richard E Leakey (2013) Amazon.com;

“Evolutionary History of the Robust Australopithecines” by Frederick E. Grine Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Cave of Bones” by Lee Berger (2023) Amazon.com;

“Born in Africa: “The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith Amazon.com;

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Lucy

Lucy Much of what is known about Australopithecus afarensis is based on "Lucy" — a large part of the skeleton and 40 percent of a skull of a single individual found in 1974 in Hadar in the Great Rift Valley in the Afar region of northern Ethiopia by anthropologist Donald C. Johanson of Arizona State University. Lucy's bones have been dated to be 3.18 million years old. She and Ardi (See Ardipithecus) are the most complete old hominin skeletons ever found. Before Lucy was discovered the most complete remains were less than a 100,000 years old.

Johanson and his student, Tom Gray, were searching for ancient animal bones on the parched terrain near the village of Hadar in northern Ethiopia. The chance finding of a piece of arm bone led them to uncover more remains of Lucy. That evening as the team celebrated at camp the Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds came on providing the scientists with a name for their discovery. Eventually, Johanson and his team gathered about 40 percent of the skeleton. Johanson is now director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University

Lucy was small — about 1.07 meters tall — but fully mature. Her skeleton proved that she walked upright but the incompleteness of the skeleton the lack of a complete skull left many unanswered questions. Lucy had a partial but well-preserved pelvis, which was how anthropologists knew she was female. The pelvis and upper leg bones fit together in a way that showed she walked upright on two legs. No feet bones were preserved, but later discoveries of A. afarensis do include feet and indicate bipedal walking as well. [Source: Jan Simek, Professor of Anthropology, University of Tennessee, The Conversation, November 1, 2021]

Some scientists later suggested that Lucy may have been a male because her pelvis hole was heart shaped and too small for a baby to slip through. Peter Schmid and Martin Häusler, anthropologists at the university of Zurich, wrote in the mid 1990s: "Lucy's pelvis has more male traits than female characteristics," they told National Geographic. "The only reason you would say Lucy is a female is her small size."

Lucy has been described as the world’s most famous hominin fossil. After her discovery she was taken to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Johansen’s home institution at the time. There molds and casts were made and distributed and the bones themselves were carefully studied. Since 1980 she has resided in a vault at the National Museum of Ethiopia and was only displayed twice.

In 2007, Lucy’s skeleton began a six-year tour of the United States, starting at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, as part of an effort by Ethiopia to raise money for its museums and science projects. Among those who objected to the tour was paleontologist Richard Leakey and the Smithsonian Institution. They said no matter how careful handlers were with the skeleton it was likely to suffer some damage. Leakey called the whole idea of the tour “a form of prostitution.”

Desi and the Three-Year-old Child

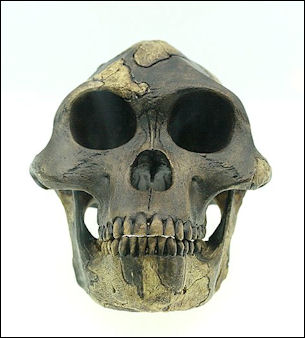

The first reasonably complete skull of “Australopithecus afarensis” was discovered in 1992 by American and Israeli scientists at a site near Hadar, Ethiopia, about a mile away from where the skeleton of Lucy was found. Nicknamed "Desi" or "Ricky" as in the husband of Lucille Ball but known to scientists as AL 444-2, the skull belonged a 3-million-year-old male. Reconstructed from nearly 60 fossil fragments, it measured five inches across, making it the largest Australopithecus skull found. AL 444-2 was considerably larger than Lucy.

Australopithecus afarensis AL 444-2 was found by Dr. Yoel Rak of Tel Aviv University and two Ethiopian assistants near their campsite. The newly exposed skull was scattered in more than 200 rock-encrusted fragments. The position of the fragments indicated that they belonged to a single individual. Schmid and Häusler assert that Lucy and Desi belong to two distinct Australopithecus species — one large and one small.

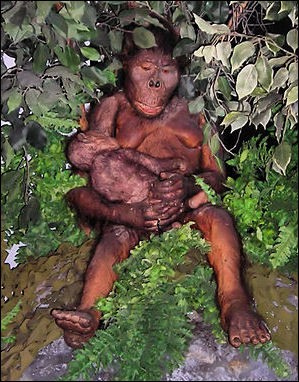

The discovery a three-year-old female “Australopithecus afarensis” in Ethiopia was announced in a September 2006 article in Nature. Dated to 3.3 million years ago and nicknamed the Dikika baby after the region where she was found in December 2000, she is the youngest “Australopithecus afarensis” ever found and the oldest example of the species, predating Lucy by about 150,000 years.

The Dikika baby was discovered by a team lead by Zeresenay Alemseged, an Ethiopian paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, in region named Dikiko (“nipple” in the local Afar language), just across the Awash River from Hadar where Lucy was found. One of Alemseged’s assistants Tilahu Gebreselassie spotted Dikika’s face peering out from a slope with much of her body entombed in sandstone. Her age of three was determined by the fact that her permanent molars had not yet emerged. [Source: Christopher Sloan, National Geographic, November 2006]

The Dikika baby is not only very old she is the most complete early hominin infant ever found and arguably the best fossil of her species. Unlike Lucy, she has fingers, a foot, a complete torso and face. The shape of her shoulders resembles a young gorilla’s, suggesting that she could climb trees, but the angle of femur from knee to hip is close to that of modern humans, implying she could walk efficiently two legs. She also possessed a hyoid bone, a bone that later became crucial to human speech. Her feet had not yet been extracted from the stone in 2006. Scientists want to see if she had an opposable big toe like a chimps or a unopposable toe like a human, which make walking easier. The brain was 330 cubic centimeters in size, about the same as a three-year-old chimp.

Australopithecus afarensis Skull and Body Features

Lucy skeleton Skull Features: More apelike than human: ape-like face, small ears, large canines, no chin, flared cheeks, flat nose, low forehead, simian-like overhanging browridge over the eyes, pronounced incisors and canine teeth. The mid-face jutted out more than human's face but less than an ape's. The jaw juts forward. Ape-like upper canine fangs extend further out than the other teeth. The large teeth used for grinding vegetation. Teeth examined under a microscope reveal marks made by food stripped off rough vegetables.

Body Features: Dense limb bones indicate great muscular strength. Long ape-like arms; cone-shaped thorax and large belly. Hips, knees and ankles were suited for an upright stance and bent-kneed, two-legged gait somewhat similar to humans. Curved fingers and toes and upward tilting shoulders indicated that her limbs were suited for climbing trees but the arrangement of her hips and pelvis would have had made it difficult to climb trees. Scientists speculate the Lucy spent most of her time on the ground but probably climbed in trees to seek fruit and shelter and possible to sleep. Lucy may . Maybe dark skinned and hairy.

From the waist down “Australopithecus afarensis” is very human-like, with kneecaps similar to those of modern humans and a femur that is angled in such a way to accommodate bipedal movement. From the waist up it is more ape-like. The shoulder blades are similar to those of a gorilla. The fingers are long and curled like a chimpanzee’s. The face is long and projecting and the nose is flat like that of a chimp.

Unlike chimpanzees, Lucy had a relatively small birth canal in her pelvis bone, which made giving birth much more difficult and dangerous for her than a chimpanzee. The smaller birth canal was an adaption made for an upright posture and easier bipedal movement. Human beings are the only species of mammal in which the female is fertile all the times instead of during restricted periods. Some have speculated that the change to year-round fertility may have begun with Australopithecus.

Australopithecus afarensis Size and Sex Differences

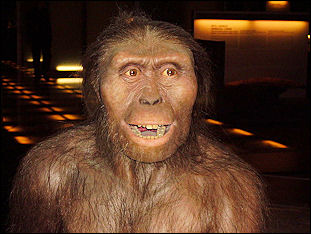

A. afarensis reconstruction Lucy's 3.18-million-year-old skeleton suggested a hominin that was only 1.07 meters (3½ feet) tall and weighed around 30 kilograms (65 pounds). The skull of another “ Australopithecus afarensis” found in 1992 indicated a much larger creature — over 1.52 meters (five feet tall) and over 50 kilograms (110 pounds).

One nagging question in early hominin anthropology has been whether or not “A. afarensis” was one species or a group of "loosely related species," a question that arose because of the large differences in the size of discovered “ afarensis” bones discovered.

Since a the ulna (a part of the forearm) from the larger hominin discovered in 1992 matched the ulna of Lucy, exactly except it was smaller, it was reasoned that the differences in bone size have attributed to the size difference between males and females.

Henry McHenry of the University of California at Davis believed that hominin stature remained stable between 4 and 2 million years ago, with males tending to be about 50 percent larger than females. This sexual differentiation pattern is consistent with gorilla and orangutan males which weigh almost twice as much as females. Male chimps are only slightly larger than chimp females.

Australopithecus Afarensis Diet Changes 3.5 Million Years Ago

Australopithecus afarensis — the species that includes Lucy — had different diets from their ancestors An analysis teeth from extinct fossils has found that they expanded their diets about 3.5 million years ago to include grasses and possibly animals. Before this, humanlike creatures – or hominins – ate a forest-based diet similar to modern gorillas and chimps. Researchers analysed fossilised tooth enamel of 11 species of hominins and other primates found in East Africa. The findings appeared in four papers published in PNAS journal. [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC News, June 4, 2013 |::|]

Melissa Hogenboom of the BBC wrote: “Like chimpanzees today, many of our early human ancestors lived in forests and ate a diet of leaves and fruits from trees, shrubs and herbs. But scientists have now found that this changed 3.5 million years ago in the species Australopithecus afarensis and Kenyanthropus platyops. Their diet included grasses, sedges, and possibly animals that ate such plants. They also tended to live in the open savannahs of Africa. The new studies show that they not only lived there, but began to consume progressively more foods from the savannahs. |::|

where Australopithecus Afarensis lived

“Researchers looked at samples from 175 hominins of 11 species, ranging from 1.4 to 4.1 million years old. It is not yet clear whether the change in diet included animals, but “the possible diets of some of our hominin kin” has been considerably narrowed down, Dr Matt Sponheimer, lead author of another of the papers, told BBC News. “We now have good evidence that some early hominins began using plant foods that are not used in abundance by living African apes today, and this probably led to a major change in the way they used the landscape. One consequence could be that the dietary expansion led to a habitat expansion, as they could travel to more open habitats more efficiently. We know that many early hominins lived in areas that would not have readily supported chimpanzees with their strong preference for forest fruits. It could also be argued that this dietary expansion was a key element in hominin diversification.” |::|

“The study has also answered, at least in part, what researchers have long been speculating – how so many large species of primate managed to co-exist. “They were not competing for the same foods,” said Prof Thure Cerling from the University of Utah, who led one of the research papers. “All these species who were once in the human lineage, ventured out into this new world of foods 3.5 million years ago, but we don’t yet understand why that is.” |::|

“As well as looking at non-human primates, the researchers analysed fossils from other animals from the same era and did not find any evidence of a change in diet. This combined research highlights a “step towards becoming the modern human”, said Dr Jonathan Wynn from the University of South Florida, who led the analysis of Australopithecus afarensis. “Exploring new environments and testing new foods, ultimately might be correlated with further changes in human history.” These four complementary studies give a persuasive account of shifts in dietary niche in East African hominins, Dr Louise Humphrey from the Natural History Museum in London, told BBC news. |::|

Australopithecus afarensis and Bipedalism

Even though Australopithecus afarensis stood upright, it is far from an open and shut case that it was a completely bipedal creature.”A. afarensis” was probably equally at home in the trees and on the ground. One anthropologist described “A. afarensis” as "bipedal from the waist down and arboreal from the waist up." Unlike chimpanzees, whose spines curve forward for the knuckle walking style of advanced primates, “ afarenis” had a spine like modern humans that curved and stood upright to bring the pelvis, legs and feet under the trunk and head, a position ideal of bipedal walking.

The walk of “ afarenis” was a cross between a human and a gorilla. Studies based on Lucy's skeleton and footprints made by 3.6-million-year-old hominins at Laetoli, Tanzania suggest that “aferensis” rotated her trunk and waddled a bit like a gorilla when she walked. Skeletal differences between the sexes seem to indicate that female “ A. afarensis” were better at swinging through the trees while males appeared to better at walking. Meave Leakey told Time, "They weren't nearly as efficiently upright as we are, and they had a form of locomotion that we don't know today because there isn't anything equivalent.” Zeresenay Alemseged told National Geographic, “I see “A. afarensis” as foraging bipeds but climbing trees when necessary, especially when they were little.”

Australopithecus afarensis had a broad, human-like pelvis; a foot with an unopposable big toe that lined up with the other toes; and a thigh bone whose top was dense enough to take the vertical stress of the upper body while walking upright. Scientists at the University of Liverpool think that Lucy probably walked in a similar fashion to modern humans based on entering Lucy's limb proportions into a computer model used in robot design. They found that with her limbs, walking like an ape with a bent-knee, bent-hip posture was less efficient than a human upright posture.

Scientists also think that “ afarensis” was unable to run because Lucy's rib cage had an apelike funnel shape, which means that her lungs could not take in enough oxygen to cool her body efficiently when she ran. They say she would have had to pant like a dog to keep cool and would have died from heat exhaustion if she ran a long way.

Australopithecus afarensis had a broad, human-like pelvis; a foot with an unopposable big toe that lined up with the other toes; and a thigh bone whose top was dense enough to take the vertical stress of the upper body while walking upright. Scientists at the University of Liverpool think that Lucy probably walked in a similar fashion to modern humans based on entering Lucy's limb proportions into a computer model used in robot design. They found that with her limbs, walking like an ape with a bent-knee, bent-hip posture was less efficient than a human upright posture.

Scientists also think that “ afarensis” was unable to run because Lucy's rib cage had an apelike funnel shape, which means that her lungs could not take in enough oxygen to cool her body efficiently when she ran. They say she would have had to pant like a dog to keep cool and would have died from heat exhaustion if she ran a long way.

“Australopithecus afarensis” had strong arms and shoulders, long arms, flexible joints and curved fingers and toes which allowed it to easily climb trees and grab branches. The hips were pointed slightly sideways. It had a mobile hip, shoulder and ankle joints like chimpanzees. The shape of “A. afarensis’s feet indicate it may have spent some time living in trees. But its knee joints show it straightened its legs, something that bow-legged knuckle-walking chimps and gorillas can't do. Her free hands were better able to gather food. Based on the similarities of the structure of Lucy's radius (fore arm) with those of chimpanzee and gorillas, scientists at George Washington University have described Australopithecus afarensis as a "classic knuckle walker." The forearm bone had a ridge, like those found on chimpanzees and gorillas, that allows it to lock in position for easy knucklewalking.

A. Afarensis Had Modern-Human-Life Feet and Thus Likely Lived on the Ground

Australopithecus Afarenis had arched feet suggesting it had abandoned life in the trees and lived on the ground. Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian: “The ancestors of humans were walking upright more than 3 million years ago, according to an analysis of a fossilised foot bone found in Ethiopia. The fossil, the fourth metatarsal bone from the species Australopithecus afarensis, shows that this forerunner of early humans had a permanently arched foot like modern humans, a key requirement for an upright gait. Arches in human feet put a spring in our step: they are stiff enough to propel us forward but flexible enough to absorb the shock at the end of each stride. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, February 10, 2011 |=|]

“Scientists already knew that A. afarensis could walk on two feet but were unsure whether the creatures climbed and grasped tree branches as well, much like their own ancestor species and modern nonhuman apes. The fourth metatarsal, described on Thursday in Science, shows that A. afarensis moved around more like modern humans. "Now that we know Lucy and her relatives had arches in their feet, this affects much of what we know about them, from where they lived to what they ate and how they avoided predators," said Carol Ward, a professor of integrative anatomy at the University of Missouri-Columbia who led the analysis of the fossil. “The development of arched feet was a fundamental shift toward the human condition, because it meant giving up the ability to use the big toe for grasping branches, signaling that our ancestors had finally abandoned life in the trees in favour of life on the ground." |=|

Australopithecus afarensis footprint

“The best-known example of A. afarensis is "Lucy", who lived in eastern Africa more than 3 million years ago. Before that, more than 4.4 million years ago, Ethiopia was populated by Ardipithecus ramidus, which seems to have been a part-time terrestrial biped, though its foot had many of the features of tree-dwelling primates, including a highly mobile big toe. |Unlike other primates, human feet have two arches, which stretch along the length of the foot and across it. Ape feet do not have these arches and are far more flexible, with a mobile large toe that is useful for climbing trees and holding onto branches. |=|

“These ape-like features are not present in the foot of A. afarensis, however. Given that its foot was more like that of modern humans, scientists think that A. afarensis no longer depended on the trees for refuge or resources 3 million years ago. "Arches in the feet are a key component of human-like walking because they absorb shock and also provide a stiff platform so that we can push off from our feet and move forward," said Ward. "People today with 'flat feet' who lack arches have a host of joint problems throughout their skeletons. Understanding that the arch appeared very early in our evolution shows that the unique structure of our feet is fundamental to human locomotion. "If we can understand what we were designed to do and the natural selection that shaped the human skeleton, we can gain insight into how our skeletons work today. Arches in our feet were just as important for our ancestors as they are for us." |=|

“Isabelle De Groote, a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, said: "These findings confirm that our human ancestors were walking on two legs by about 3.2 million years ago. "Bipedal locomotion or two-legged walking is one of the hallmarks of the human species. Older human fossils still show adaptations to spending some of their time in the trees ... for feeding or nesting, but the evidence here suggests that by 3.2 million years ago one of our ancestors, Australopithecus afarensis, was fully committed to bipedal walking."” |=|

See Separate Article: HOMININ BIPEDALISM: COSTS, BENEFITS, WALKING AND RUNNING factsanddetails.com

Laetoli Footprints

A series of 3.6 million-year-old footprints left in volcanic ash by an early hominin were discovered in Laetoli, Tanzania. The 69 prints were made by two adults that appear to have walked side by side. The two sets of prints parallel each other, about a foot apart. The Laetoli footprints were likely made by Australopithecus afarensis individuals. They made headlines in the 1970s as the earliest clear evidence of upright walking by our ancestors.

One set seems to be made by a large male, and the other by a smaller female. Inside the larger prints are prints from a third individual, possible a child. At one point the prints are so close together the hominins could have been holding hands. At another place the small one seems to be walking behind the large one. At another point the smaller one halted in mid stride, perhaps to turned around and look at something.

The Laetoli prints provides the best evidence that early hominin walked like modern humans — body upright, legs striding side by side. Unlike the feet of chimpanzee, which have a splayed toe that separates from the foot like a thumb, the Laetoli tracks are made by feet with all the toes parallel to the axis of the foot (the same as humans).

See Separate Article: LAETOLI FOOTPRINTS factsanddetails.com

”Kadanuumuu” Confirms Australopithecus afarensis Walked Upright

Brendan Borrell wrote in Archaeology magazine, For the last 35 years, the short-legged “Lucy” skeleton has led some scientists to argue that Australopithecus afarensis didn’t stand fully upright or walk like modern humans, and instead got around by “knuckle-walking” like apes. Now, the discovery of a 3.6-million-year-old beanpole on the Ethiopian plains — christened “Kadanuumuu,” or “Big Man — in the Afar language — puts that tired debate to rest. The new fossil demonstrates these early human ancestors were fully bipedal. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2011]

Many dozens of A. afarensis fossils have been uncovered since Lucy was discovered in 1974, but none as complete as this one. Kadanuumuu’s forearm was first extracted from a hunk of mudstone in February 2005, and subsequent expeditions uncovered an entire knee, part of a pelvis, and well preserved sections of the thorax. [Ibid]

“We have the clavicle, a first rib, a scapula, and the humerus,” says physical anthropologist Bruce Latimer of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, one of the co-leaders on the dig. “That enables us to say something about how [Kadanuumuu] was using its arm, and it was clearly not using it the way an ape uses it. It finally takes knuckle-walking off the table.” At five and a half feet tall, Kadanuumuu would also have towered two feet over Lucy, lending support to the view that there was a high degree of sexual dimorphism in the species. [Ibid]

Laetoli footprints

Using Computer Modeling to Work Out How Lucy Walked

A study by a team led by Dr. Ashleigh L.A. Wiseman of the University of Cambridge, published in June 2023, in the journal Royal Society Open Science, took a deeper look at how Lucy walked by computer modeling her muscles. Wiseman told CNN: “In the fossil record we are left looking at the bare bones. But muscles animate the body — they allow you to walk, run, jump and even dance. So, if we want to understand how our ancestors moved, we first need to reconstruct their soft tissues.” [Source: CNN June 14, 2023]

According to CNN: Wiseman and her colleagues developed a method called polygonal muscle modeling to understand the shape and size of her muscles and how she used them to move, assessing whether it was like the crouched waddle of an upright chimpanzee or the stance of a human. Wiseman used scans of Lucy’s fossil and data from humans to build a three dimensional model of the leg and pelvis muscles of Australopithecus afarensis. After collecting data from MRI and CT scans of muscle and bone structures in modern humans, the researcher digitally created a musculoskeletal model. Then, she used scans of Lucy’s fossil to determine how her joints were articulated and moved in life. Wiseman layered in 36 muscles in each leg using the “muscle map” from the modern human data, combined with “muscle scarring,” or the discernible traces of muscle connection that are detectable in fossils.

Wiseman’s model showed that while a modern human’s thigh was about 50 percent muscle mass, with the rest attributed to fat and bone, Lucy’s thigh would have been nearly 75 percent muscle. Overall, Lucy’s leg muscles were much larger and took up more space than those of modern humans. “Lucy lived 3.2 million years ago on the African savannah. She would need to have walked over uneven ground and explored a mixture of forested environments and open grassland,” Wiseman said. “Larger muscle mass typically means greater muscle force, and it is very unsurprising to find that the reconstructions of Lucy’s muscles demonstrates that she had greater muscle mass than a human, enabling her to move freely between these different environments.”

Paleoanthropologists have wondered about Lucy’s posture because her skeleton differs from modern humans. Humans have a stable stance with fully straightened legs, but when chimpanzees stand upright, they can’t straighten their legs. They walk with a crouched posture due to their bent hips and knees, which is why chimps largely walk on all fours. The 3D model showed that the leverage of Lucy’s knee extensor muscles meant that she could stand erect like modern humans. “I was very surprised to find that the knee extensors (those muscles that produce and maintain a straight knee when you stand upright) were so comparable to the human,” Wiseman said. “This means that Lucy could stand and likely walk as efficiently as we can.”

Australopiths such as Lucy lived in an environment that included both open grasslands and dense forests, and had bodies adapted to thrive both on the ground and in trees. “Lucy likely walked and moved in a way that we do not see in any living species today,” Wiseman said. “If Lucy was a biped just like we are and walked exclusively on two legs, then she should be able to move in similar ways as we can,” Wiseman said.

Lucy Was an Adept Tree Climber

A. afarensis reconstruction Scientists using sophisticated CT scanning on Lucy’s fossil bones determined that she spent a lot of time in the trees. Reuters reported: “Researchers announced the results of an intensive analysis of the 3.18 million-year-old fossils of Lucy, a member of a species early in the human evolutionary lineage known as Australopithecus afarensis. The scans of Lucy's arm bones showed they were heavily built, like those of chimpanzees. This indicates that members of this species spent significant time climbing in trees and used their arms to pull themselves up in the branches. [Source: Reuters, December 1, 2016]

Scientists already knew the species' feet were adapted for walking upright on two legs, rather than grasping trees, but had wondered about whether its members still spent time in trees like their ancestors. Chimpanzees, the closest living relative of humans, spend a lot of time in trees. The researchers performed high-resolution X-ray CT scans on Lucy's fossils at the University of Texas and compared the findings to data on the bones of modern humans and chimpanzees. "The debate about whether or not Lucy climbed trees has been raging ever since her discovery 42 years ago this month — our study brings that debate to a close," said University of Texas paleoanthropologist John Kappelman, one of researchers in the study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Kappelman said: “"It may seem unique from our perspective that early hominins like Lucy combined walking on the ground on two legs with a significant amount of tree climbing, but Lucy didn't know she was unique." Tthe study's lead author, Christopher Ruff, a professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said: "Our analysis required well-preserved upper and lower limb bones from the same individual, something very rare in the fossil record."

According to Archaeology magazine: A 3.32-million-year-old child’s foot from Dikika, Ethiopia suggests that Australopithecus afarensis children were surprisingly good climbers. Although the female toddler could walk upright, her foot’s skeletal structure indicates that she retained some ape-like traits, such as the ability to grasp objects with her feet. This would have helped A. afarensis children cling to their mothers or climb trees, especially when confronting danger. These features are not found in the species’ adult skeletons, implying that as individuals grew up and spent more time upright, their bodies changed. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2018]

Lucy Died in a Fall from a Tree?

In 2016 University of Texas paleoanthropologist John Kappelman said that Lucy might have died after falling out of a tree. Kappelman conducted a new analysis of the bones and concluded that a number of cracks found by his team matched the traumatic fractures seen in humans that suffer serious injuries from high falls. The theory was met with scepticism by many researchers, who pointed out that a lot can happen to a skeleton in 3.2 million years. For example, Lucy’s body might have been crushed by stampeding animals before her bones were covered in sediment that changed to rock.

Kappelman hypothesized that Lucy foraged on the ground during the day and sought safety in the trees at night and said her injuries indicated she fell from a height of more than 12 meters. “The consistency of the pattern of fractures with what we see in fall victims leads us to propose that it was a fall that was responsible for Lucy’s death,” Kappelman said. “I think the injuries were so severe that she probably died very rapidly after the fall.” [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, December 14, 2016]

But the claims, published in the journal Nature, were widely criticized in academic circles. “There is a myriad of explanations for bone breakage,” Lucy discoverer Donald Johanson of Arizona State University, told The Guardian. “The suggestion that she fell out of a tree is largely a “just-so story” that is neither verifiable nor falsifiable, and therefore unprovable.” Tim White, a paleoanthropologist at the University of California in Berkeley, said the cracks were no more than routine fossil damage. “If paleontologists were to apply the same logic and assertion to the many mammals whose fossilised bones have been distorted by geological forces, we would have everything from gazelles to hippos, rhinos, and elephants climbing and falling from high trees,” he said.

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “Kappelman became intrigued by some of the cracks in Lucy’s bones after examining high resolution x-ray scans of the fossils. The cracks had been described before and put down to natural processes such as erosion and fossilisation. But Kappelman thought there might be another explanation. |=|

“Working with Stephen Pearce, an orthopaedic surgeon, the scientists identified cracks in more than a dozen bones, ranging from the skull and spine to the ankles, shins, knees and pelvis, which look like compressive fractures sustained in a fall. One injury to the right shoulder matches the kind of fracture seen when people instinctively put their arms out to save themselves, the scientists believe. Kappelman calls it “a unique signature” for a fall and evidence that the individual was conscious at the time. |=|

“From the scientists’ calculations, Lucy, who weighed less than 30kg, could have suffered similar injuries in a fall from about 15 metres. If Australopithecus afarensis climbed trees to nest, the animals could have spent hours a day at this or even greater heights. “We know that chimps fall out of trees and often it’s because they step on a branch that turns out to be rotten, and boom, down they come,” said Kappelman. “Based on clinical literature these are severe trauma events. We have not been able to come up with a reasonable way that these could be fractured postmortem with the bones lying on the surface or even if the dead body was being trampled on. If somebody is trampled on the bone breaks in a different way. It doesn’t break compressively,” said Kappelman. |=|

“But Johanson is not impressed. The cracks on Lucy’s bones are similar to the damage seen on other early human and ancient mammal fossils throughout Africa and the rest of the world, he said. “We don’t know how long the fossilisation process takes, but the enormous set of forces placed on the bones during the build up of sediments covering the bones is a significant factor in promoting damage and breakage,” he added.

“One of White’s major complaints is that the scientists fail to prove beyond doubt that the cracks in Lucy’s bones occurred around the time of death. “Such defects created by natural geological forces of sediment pressure and mineral growth are very common in fossil assemblages. They often confuse clinicians and amateurs who imagine them to have happened around the time of death,” White said. “Every single element of the Lucy fossil has cracks. The authors cherry pick the ones that they imagine to be evidence of a fall from a tree, leaving the others unexplained and unexamined.” Kappelman concedes that we can never know for sure what happened. “None of us were there. We didn’t see Lucy die,” he said. “Thinking about testing this idea, it’s hard to get someone to fall out of a tree, but we have tests going on every single day in every emergency room on planet Earth when people walk in with fractures from falls,” he said. |=|

World's Earliest Tools Made by Australopithecus afarensis?

Don Johanson, one of discoverers of Lucy

In 2009, 3.4-million-year-old bones — found in Dikika, Ethiopia, near site where a Lucy-like hominin was discovered — with slashes, parallel marks and other cut marks that appear to have been made with stone tools, was presented as evidence that stone tools were produced more than 800,000 years than earlier thought and they could have been made by a possible human ancestor such as Lucy (Australopithecus afarenis).

Archaeology magazine reported: Paleoanthropologists in Ethiopia may have discovered the earliest evidence of stone-tool use. Some 3.3-million-year old bones found near the site of Dikika have marks that look like they were made by tool-using hominins. If this evidence is legitimate, it could mean that one of the tool-using behaviors — a hallmark of humans — dates back to our relatively small-brained ancestors the Australopithecines. Prior to this discovery, the earliest evidence of tool use had come from the site of Gona, which was occupied by Homo habilis 2.6 million years ago. [Source: Brendan Borrell,Archaeology magazine, November/December 2010]

Curtis Marean of Arizona State University examined the bones, which include a femur with gashes running across the bone. "I could tell within minutes that this was stone-tool-inflicted," he says. A rib bone also appeared to have been pounded open with a stone wielded like a hammer. But when the study was published in Nature in August 2010, the findings were greeted with suspicion.

Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo of Complutense University in Madrid is an expert in the processes that affect bones as they fossilize. He says he has seen similar marks from Ethiopian bones as old as 6 million years, but believes those marks could have been caused by animals trampling the bones or by crocodile bites. Stanley Ambrose of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign calls the report "premature" and says that excavation of the bone-bearing sediments should be conducted to see if there is other evidence of butchery. Confirmation may come from other material first. "People have fragments from that age that they think are stone-tool modified, but they have just been a little hesitant to step out and make the case," says Marean.

See Separate Article: OLDEST STONE TOOLS AND WHO USED THEM factsanddetails.com

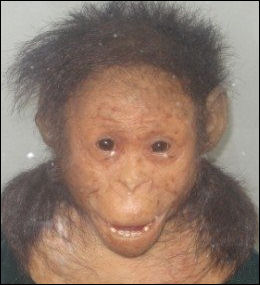

Difficulty Reconstructing What Lucy Looked Like

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: “Visit more than one natural history museum or flip through a handful of scientific textbooks, and you’ll quickly notice how much disagreement there is about Lucy’s physical appearance. No one can agree on what Lucy or “AL 288-1” looked like. Why is that? In a February 2021 article, “Visual Depictions of Our Evolutionary Past,” published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, a team of scientists from the University of Adelaide, Arizona State, the University of Zurich, and Howard University set out to discover why this is and to compile their own, scientifically grounded, reconstruction. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 27, 2021]

Lucy

“The differences in the depictions of Lucy are not small and, as the authors of the study show, reflect ideological biases about the past. For example, the Creation Museum in Kentucky, which is run by Answers in Genesis, depicts Lucy as a knuckle dragging ape. This is despite the fact that, as Adam Benton has discussed, there is a broad consensus among scientists is that Lucy was a biped who walked on two feet. As the authors of the new study write, “the decision to reconstruct this specimen as a knuckle-walker is an obvious error” but it has significance for whether we see Lucy as important evidence about our ancestors or “just an ape.”

“Even in less extreme cases, there are considerable differences in the way that artistic reconstructions show Lucy’s ribcage, facial features, hair, and skin tone. As Karen Anderson has written in an important work, the problem is widespread in hominin reconstructions, which “often convey inaccurate scientific information.” Maciej Henneberg, one of the co-authors of the study, explained to The Daily Beast that depicting a hominin’s body and face involves the reconstruction both of hard tissues (bones and teeth) and of soft tissues (muscles, skin, guts, internal organs, etc). Along the way, numerous decisions have to be made and these decisions, Henneberg told me, substantially affect how people relate to the reconstructed specimen (be it Lucy or another example). Facial features are especially important in this process, Henneberg said, because “Humans communicate by looking at each other’s faces, so we pay a lot of attention to faces of others. Thus, the reconstruction of the face of an animal or a human ancestor gives important personal information — the ‘first impression’ of the reconstructed individual.

“In their own reconstruction, undertaken over 6 years as a collaboration between the scientists and Cuban-American artist Gabriel Vinas, clearly explains the group’s decision making process. Vinas explained to The Daily Beast “For the image showing Lucy and Taung, we produced it to highlight how different choices in surface treatment, color, and hair quantity can differ immensely based on the whims of practitioners or their expert consultants which can result in the kinds of inconsistencies we see all over the world regarding these features.”

“Rather than relying upon “intuitive” methods of reconstruction, which the team found “too imprecise” they inferred muscle proportions from previous studies. They are transparent about the gaps in our knowledge. As Vinas told me: “Lucy’s cranial bones are almost entirely missing … ‘putting a face’ quite literally to the celebrity-status skeleton can seem like a minor form of procedural trespassing; in a way, ‘a white lie’ that parents are comfortable telling their children.” In Vinas and the team’s facial reconstructions Lucy is reconstructed with bonobo-like features while the reconstructed Taung child (another well-known set of remains) is shown with skin tone “more similar to that of anatomically modern humans native to South Africa.” The rationale for the difference in skin tone, we are told, is that scientists do not have “an empirical method for reliably reconstructing” the melanin concentration in austalopithecines. Some scientists may disagree with details of these reconstructions, but at least they (and we) know why these choices were made. Vinas added, “to remain intellectually consistent, we must say that none of these models or images in this publication should be touted as representative of the actual appearances of those individuals regardless of how technically impressive they are.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Laetoli footprints from Sciencephoto

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024