LAETOLI FOOTPRINTS

Laetoli footprints A series of 3.6 million-year-old footprints left in volcanic ash by an early hominin were discovered in Laetoli, Tanzania. The 69 prints were made by two adults that appear to have walked side by side. The two sets of prints parallel each other, about a foot apart. The Laetoli footprints were likely made by Australopithecus afarensis individuals. They made headlines in the 1970s as the earliest clear evidence of upright walking by our ancestors.

One set seems to be made by a large male, and the other by a smaller female. Inside the larger prints are prints from a third individual, possible a child. At one point the prints are so close together the hominins could have been holding hands. At another place the small one seems to be walking behind the large one. At another point the smaller one halted in mid stride, perhaps to turned around and look at something.

The Laetoli prints were found with prints from an ancient horse, rhinoceros and antelope. Most anthropologists believe the hominin prints were made by an Australopithecus species but they are not sure whether they were made by afarensis species like Lucy, another known species, or a mystery species whose fossilized bones have not yet been discovered.

The hominins that made the prints had a humanlike stride, wrote paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson in National Geographic: "a strong stride with the heel, followed by a push-off with the big toe to propel the body forward. Their big toes do not splay out from the rest of the foot like the divergent big toes all other primates have."

Laetoli is a stark landscape northwest of the Ngorongoro Crater in northern Tanzania. Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The 3.6-million-year-old footprints at Laetoli, Tanzania, have fascinated archaeologists since they were discovered in 1976. These prints preserve, in volcanic ash, that most characteristic of behaviors—the act of walking—among early humans. Understanding how early humans moved is important because efficient, upright locomotion was one of the first evolutionary traits that set them apart from other ape species. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology Volume 64 Number 6, November/December 2011]

See Separate Articles: AUSTRALOPITHECINES: CHARACTERISTICS, POSSIBLE TOOL USE AND DIVERSITY factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AND EARLY HOMININ FOOD, DIET AND EATING HABITS factsanddetails.com ; DIFFERENT AUSTRALOPITHECUS SPECIES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFARENSIS: LUCY, DESI, BIPEDALISM AND TREES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFRICANUS: TAUNG CHILD, LITTLE FOOT AND MRS. PLES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA: DISCOVERY SITE AND SIGNIFICANCE factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; PARANTHROPUS AND KENYANTHROPUS (ALSO CLASSIFIED AS AUSTRALOPITHECINES) factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Volume 1: by Terry Harrison Amazon.com;

“Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context: Volume 2: Fossil Hominins and the Associated Fauna” by Terry Harrison Amazon.com;

“Lucy: the Beginnings of Humankind” by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey (1981) Amazon.com;

“Lucy's Legacy: The Quest for Human Origins” by Dr Donald Johanson and Kate Wong (2009) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Born in Africa: “The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith Amazon.com;

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Significance and Discovery of Laetoli Footprints

The Laetoli prints provides the best evidence that early hominin walked like modern humans — body upright, legs striding side by side. Unlike the feet of chimpanzee, which have a splayed toe that separates from the foot like a thumb, the Laetoli tracks are made by feet with all the toes parallel to the axis of the foot (the same as humans).

The large gap between the large toe and the rest of the toe meant the Laetoli creature no longer spent much time climbing trees. There was also no evidence of knuckle walking of any kind. Little Foot, a 3- to 3.5- million-year-old fossil foot from a “ Australopithecus africanus” foot found in South Africa, has an ape-like splayed toe and humanlike ankle which shows that feet ideal of bipedalism evolved slowly.

The Laetoli footprints were discovered in Tanzania by a worker on Mary Leakey's team after falling down trying to dodge a piece of elephant dung flung at him by one of his friends. The footprints were found in rock created by ash created by an eruption from the nearby Sadiman volcano.Accurate dating was made possible by measuring the radioactive decay of particles found in the ash.

A year after the site was discovered, it was covered in river sand filled with seeds of acacia trees that sprouted and almost destroyed the tracks with their roots. In 1993, an emergency operation was launched to kill the trees and excavate the tracks. To preserve the tracks for future generations a granular fill and geo-textile of synthetic material was placed on top of prints at Laetoli to preserve them. The geo-textile kept the granular fill in place while allowing air to circulate and killing off damaging roots with a herbicide that was developed to prevent weeds from growing on foot paths in real east developments.

Short Legs, Running and Aggression

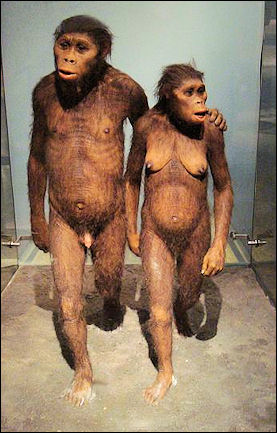

Laetoli footprints recreation The short legs of the Australopithecus were long thought to be needed to climb trees. In a paper published in the journal Evolution in March 2007, David Carrier of the University of Utah argued that short legs more likely evolved to make males better fighters by giving them a lower center of gravity and better balance. Their superior fighting ability in turn made them attractive to females and the trait was passed on.

“Australopiths maintained short legs for two million years because a squat physique and stance helped the males fight over access to females,” Carrier told the Times of London. “With short legs your center of mass is closer to the ground. It’s going to make you more stable so that you can’t be knocked doff your feet as easily. And with short legs you have great leverage as you grapple your opponent.”

Carrier analyzed the heights and limb lengths of modern great apes and compared this data with with levels of aggression. He found that for each primate, apart from modern man, the female had relatively longer legs than males and this suggested a link between leg length and aggression. Modern man is the exception to this rule in that it has long legs and is highly aggressive. Carrier said they “traded advantages of being able to stand their ground for the ability to run away or walk distances.”

Ancient human species such as the australopithecines were unable to run very fast for long periods because they lacked Achilles tendons. With the exception of gibbons all close human relatives — namely chimpanzees, gorillas orangutans — lack Achilles tendons and likely early human ancestors lacked them too. Bill Sellars of the University of Manchester told the Times of London. “Without Achilles tendons you are rubbish at running. You can’t go very fast and you use an awful lot of food to get from A to B. Humans and, strangely, gibbons have great big Achilles tendons...Pursuit running pretty much relies on running...If Lucy has no Achilles tendon she’d be far to inefficient to have been any kind of pursuer. It wouldn’t have stopped her from scavenging, but she wouldn’t have been much of a hunter.” Running is thought to have developed about 2 million years ago. It is a pogo-stick-like motion using tendons in the legs as elastic springs.

3-D Laser Scans Show Laetoli Footprints Were Made Surprisingly Modern Feet

In 2011, a team led by Robin Crompton of the University of Liverpool published a study of the Laetoli footprints using 3-D laser scans that appeared to show that Australopithecus afarensis had anatomically modern feet, approximately 2 million years before they were thought to have evolved. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology Volume 64 Number 6, November/December 2011 ^^]

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Crompton's study analyzed 11 of the Laetoli footprints likely to have been made by the same individual, and combined the scanned results to come up with a single composite footprint. The method revealed a detailed picture of how forces were transmitted between the foot and the ground. The composite print was compared to modern ones made by apes and humans walking over a plate that measures downward force. The Laetoli print showed evidence of an arch in the midfoot and a forward-pointing big toe that pushed off with each step, traits similar to those of modern human feet. ^^

New Laetoli Footprints

Australopithecus afarensis footprinte

Thirteen 3.66 million-year-old footprints were found in 2015 about 150 meters away from the famed Laetoli footprints of a similar age found by the Leakeys in the 1970s, The footprints are impressions left in volcanic ash that later hardened into rock. Their comparatively large size, averaging a bit over 26 centimetres, suggest they were made by a male member of the species known as Australopithecus afarensis. [Source: Associated Press, December 14, 2016]

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian“The markings reveal that the ancient human relatives walked side by side for at least 30 metres. The footprints were laid down in a layer of ash that was subsequently buried, but which when moistened retained the tracks like clay. A first analysis of the footprints suggests that they were made when a male, three females and a child passed through what is now Laetoli in the African country. The individuals almost certainly belong to a species of hairy bipedal ape called Australopithecus afarensis which is known to have lived in the region. The most famous member of the species, known as Lucy, lived in the Hadar area of Ethiopia 3.2 million years ago. A mere 1.1 metre tall, she was tiny in comparison to those who left their marks in Tanzania. The male stood more than half a metre taller, at 165 centimeters (5ft 5in), making him the largest Australopithecus yet recorded. His impressive stature – for his species – led researchers to nickname him Chewie after the towering hairy Wookiee in Star Wars.[Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, December 14, 2016 |=|]

“Researchers unearthed the tracks by accident when they began to excavate test pits that had been called for as part of an assessment of the impact of building a proposed museum on the site in Tanzania. Marco Cherin, a palaeontologist at the University of Perugia in Italy, helped to excavate the tracks after the first prints were discovered by a team in Tanzania. “When we reached the footprint layer and started to clean it with a soft brush and saw the footprints for the first time, it was really one of the most exciting times of my life,” he said. |=|

“The layer of ash that preserved the tracks has been dated to 3.66 million years old, the same age as a similar sequence of hominin, or human ancestor, footprints found nearby by famed palaeontologist Mary Leakey in the 1970s. Researchers now want to return to the site to dig a trench that links the excavation pits and then work outwards, in the hope of revealing more tracks. “We are pretty sure that at least one more individual is waiting for us, and possibly more. Our goal is to discover new individuals,” Cherin said. |=|

New Laetoli Footprints Made by Five Individuals, Including a Big Male

Initial analysis of new Laetoli footprints suggests that they were made by a male, three females and a child. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “Having uncovered the footprints and measured them, the scientists used a number of mathematical models to calculate the heights of the different individuals. If the scientists are right that the group consisted of a tall male with three adult females and a child, it would bolster the theory that Australopithecus afarensis was polygynous, meaning that, like gorillas, males would have had several female partners at once. The adult females stood about 140 centimeters tall. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, December 14, 2016 |=|]

Laetoli footprints “Measurements of the length and width of the footprints, the angle of the gait and the stride lengths allowed the scientists to calculate rough weights for the five. The tall male came in at the heaviest, weighing 48.1kg, with the lightest only 28.5kg. “These footprints enrich our knowledge about the most ancient hominin footprints in the world,” Cherin told the Guardian. “But they tell us something about the makers too, in this case that we think there were significant differences between the males and females. This is the most striking thing. A tentative conclusion is that the group consisted of one male, two or three females, and one or two juveniles, which leads us to believe that the male – and therefore other males in the species – had more than one female mate,” Cherin added. Details of the tracks are published in the journal, eLife. |=|

“Giorgio Manzi, director of the archaeological project in Tanzania, said the evidence portrayed several human ancestors moving through the landscape after a volcanic eruption that was followed by rain. “The footprints of one of the new individuals are astonishingly larger than anyone else’s in the group, suggesting that he was a large male member of the species. In fact, the 165 centimeter stature indicated by his footprints makes him the largest Australopithecus specimen identified to date.” In being so short, it seems that Lucy was an outlier.

“William Jungers of Stony Brook University in New York said: “To judge by the profound scientific impact of the first set of Laetoli footprints, we can expect the new ones to figure prominently in future narratives of the origins of humans. They will likely stimulate new research and debate for years to come.” |=|

New Laetoli Footprints: a Big Male and a Harem?

Associated Press reported: “He stood a majestic five-foot-five, weighed around 100 pounds and maybe had a harem. That's what scientists figure from the footprints he left behind some 3.7 million year ago. He's evidently the tallest known member of the pre-human species best known for the fossil skeleton nicknamed "Lucy," reaching a stature no other member of our family tree matched for another 1.5 million years, the researchers say. Researchers named the new creature S1, for the first discovery made at the "S" site. From the footprints, they calculated that he stood about roughly five-foot-five and weighed around about 100 pounds. [Source: Associated Press, December 14, 2016 ^]

“They figured that he loomed at least more than 20 centimetres above the individuals who made the other tracks, and stood maybe 7 centimetres taller than a large A. afarensis specimen previously found in Ethiopia. "Lucy," also from Ethiopia, was much shorter at about 3½ feet. The findings are described in a report released Wednesday by the journal eLife. Authors include Giorgio Manzi of Sapienza University in Rome, Marco Cherin of the University of Perugia in Italy, and others. ^

“Nobody knows the ages or sexes of any of the track-makers, although the size of the latest footprints suggest they were made by a male. It's quite possible that the new discovery means A. afarensis males were a lot bigger than females, with more of a difference than what is seen in modern humans, the researchers say. That's not a new idea, but it's still under debate. The large male-female disparity suggests A. afarensis may have had a gorilla-like social arrangement of one dominant male with a group of females and their offspring, the researchers said. ^

“But not everybody agrees with their analysis of S1's height. Their estimate is suspect, says anthropologist William Jungers, a research associate at the Association Vahatra in Madagascar who wrote a commentary on the study. That's because scientists haven't recovered enough of an A. afarensis foot to reliably calculate height from footprints, he said. Philip Reno, an assistant anthropology professor at Penn State who didn't participate in the new work, said he believed the height estimate was in the right ballpark. But he's not convinced that S1 was really taller than the large Ethiopian A. afarensis. So rather than setting a record, "I think it confirms about the size we thought the big specimens were," Reno said. Manzi and Cherin said they can't be sure S1 was taller than the Ethiopian specimen. "We only suggest," they wrote in an email.” ^

Laetoli footprints

Were Another Set of Laetoli Prints Made by a Bear or Unknown Hominin

In the early 2020s, scientists reexamined a set of prehistoric footprints that have puzzled scientists since they were discovered in 1976. Mary Leakey first uncovered the footprints but could not determine for sure whether they were made by hominin or another animal, perhaps a bear. A new team re-excavated the confusing footprints, found at a site called Laetoli A, and made photos and 3-D scans available for other researchers to examine. The research was published in December 2021 in the journal Nature. [Source: Christina Larson, Associated Press, December 2, 2021]

Paleoanthropologist Ellie McNutt of Ohio University's Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, lead author of the study noted that the Laetoli trackways represent the oldest unequivocal evidence of bipedal locomotion in the human fossil record. "There were at least two hominins walking in different ways on differently shaped feet at this time in our evolutionary history, showing that the acquisition of human-like walking was less linear than many imagine," said Dartmouth College paleoanthropologist and study co-author Jeremy DeSilva. "In other words, throughout our history, there were different evolutionary experiments in how to be a biped." [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, December 2, 2021, 3:23 AM

“The footprints found in 1976 and re-excavated in 2019 bore different traits than those found in 1978, in particular a gait called cross-stepping. "The trackway consists of five consecutive bipedal footprints. But the left foot is crossing over the right, and vice versa. We aren't sure what this means yet," DeSilva said. "Cross-stepping sometimes occurs in humans when we are walking on uneven ground. Perhaps that explains this odd gait. Or perhaps just this individual hominin walked in a peculiar manner. Or maybe an unknown species of hominin was adapted to walk in this way," DeSilva added. Based on the footprints, the researchers estimate that the individual that made them was only a bit taller than 3 feet (1 meter), walked with a prominent heel strike, and had a big toe that stuck out to the side slightly, though not as much as in a chimpanzee.

Associated Press reported: “What's long perplexed scientists is that those tracks — broad footprints with enlarged fifth toes — don’t closely match anything scientists have elsewhere identified. “They didn’t have the right weight and foot movement to be easily identified as human, so other explanations were sought,” including that they may belong to an extinct species of bears, DeSilva said. He and other researchers returned to the site in 2019 and used Leakey’s original maps to locate the enigmatic prints, preserved in a layer of volcanic ash that had cooled and hardened.

“ McNutt studied the foot mechanics of black bear cubs at a wildlife rescue center in New Hampshire to see whether a small bear walking on hind legs could leave similar footprints. She held a tray of apple sauce to lure the cubs into walking toward her. Each footstep was recorded in a track of mud, to be analyzed. Bears walking upright first put weight on the heels of their feet, like humans, she said. “But the foot proportions aren’t the same." She concluded that the fossil footprints were not left by bears. Other factors, such as the spacing of the footprints, led the study authors to conclude that that the footprints were left by a previously unknown species of a very early human ancestor.

“Not everyone is convinced. Richard Potts of the Smithsonian said it's a toss-up between an ancient bear or an ancient human, adding that an ancient bear may have walked differently than a modern black bear. William Harcourt-Smith, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History, said he was convinced that it wasn’t a bear, but wasn’t certain it was an early human. “These prints could still belong to some form of non-human ape,” he said. If two different species were walking upright on the landscape at the same time, that suggests different simultaneous experiments in bipedalism — complicating the conventional view of human evolution as strictly linear. "That’s really cool to think about,” said Harcourt-Smith.

Hominin footprints

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Laetoli footprints from Sciencephoto and Dikika bones from Wired

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024