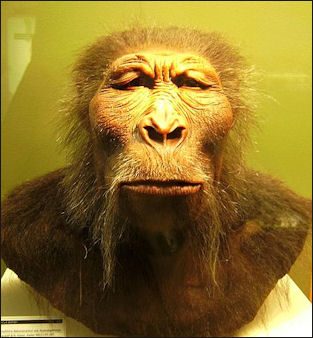

DIFFERENT AUSTRALOPITHECINES AND PARANTHAPUS SPECIES

Paranthropus boisei

Some scientists believe that “Australopithecus boisei” and “Australopithecus robustus” are distinctive enough from other early hominins to be grouped in their own separate genus “ Paranthropus” . Others say they belong in the Australopithecus genus. Paranthropus means "Beside Man” in Greek.

On the brains of the Australopithecines compared to those of Paranthropus Dean Falk, a researcher at Florida State University, told Newsweek, “Paranthropus had a teardrop shape, whereas africanus has a swooping down in the bottom where Paranthropus is sort of peaked. The structure suggest that africanus had a more developed brain for decision making and planning which Paranthropus didn’t have, explaining why its is believed to have led to a dead end.”

Australopithecus and Paranthropus (Robust Hominins)

1) Australopithecus africanus

a) A. africanus (lived about 3.3 million to 2.1 million years ago in southern Africa)

b) A. deyiremeda (lived about 3.5 -3.3 million years ago in northern Ethiopia)

c) A. garhi (lived about 2.5 million years ago in Ethiopia)

d) A. sediba (lived about 2 million years ago in southern Africa)

2) Also called Paranthropus (lived about 2.6 million to 1.1 million years ago)

a) P. aethiopicus (lived about 2.5 million years ago in southern Ethiopia)

b) P. robustus (lived about 2 million to 1.2 million years ago in southern Africa)

c) P. boisei (lived about 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania)

3) Also called Praeanthropus

a) A. afarensis (lived about 3.9 million to 2.9 million years ago at several sites in Ethiopia and Kenya)

b) A. anamensis (lived about 4.2 million to 3.9 million years ago at several sites in Ethiopia and Kenya)

c) A. bahrelghazali (lived about 3.6 million years ago in Chad)

See Separate Articles: AUSTRALOPITHECINES: CHARACTERISTICS, POSSIBLE TOOL USE AND DIVERSITY factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AND EARLY HOMININ FOOD, DIET AND EATING HABITS factsanddetails.com ; LAETOLI FOOTPRINTS <a href="https://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub360/entry-8899.html""> factsanddetails.com; DIFFERENT AUSTRALOPITHECUS SPECIES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFARENSIS: LUCY, DESI, BIPEDALISM AND TREES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFRICANUS: TAUNG CHILD, LITTLE FOOT AND MRS. PLES factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA: DISCOVERY SITE AND SIGNIFICANCE factsanddetails.com ; AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings” by Virginia Morrell Amazon.com;

“Disclosing the Past”, Mary Leakey’s 1984 autobiography Amazon.com;

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Lucy: the Beginnings of Humankind” by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey (1981) Amazon.com;

“Lucy's Legacy: The Quest for Human Origins” by Dr Donald Johanson and Kate Wong (2009) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Born in Africa: “The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Paranthropus robustus (Australopithecus robustus)

Paranthropus robustus (also known as Australopithecus robustus ) translates to "strongly and stoutly built southern man.” As its name implies it was larger and stronger than its predecessors but it had a small brained. The species lived around the same time as Homo erectus, our direct human ancestor, and was first identified from four teeth and a jaw discovered by a South African school boy in 1938. It is believed to have used bone tools. Geologic Age 1.9 million to 1.2 million years. Size: males: 1.3 meters (4 feet, 4 inches), 40 kilograms (88 pounds); females: 1.1 meters (3 feet 7 inches), 32 kilograms (71 pounds). About the same height as predecessors but more powerfully built. Brain Size: Slightly larger than predecessors. Linkage to Modern Man: Robustus and boisei may be different subspecies of a single, variable species. Believed to be an evolutionary dead end. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, November 1985 [┹]

Discovery Sites: Found in 1938 Krombraai, South Africa by Gert Terblanche and Robert Broom. No remains found in east Africa. A nearly complete skull was found in 1950 in Swartkrans, South Africa by E. Quarryman Fourie. Housed in Transvaal Museum, Pretoria. Remains have also been found in Makapansgat, South Africa. A number of Australopithecus robustus fossils have been found at a cave site in South Africa called Drimolen and the Drimolen Main Quarry north of Johannesburg. Among the discoveries is the most complete “A. robustus” skull ever found, dated to be 2 million years old. So far almost 80 “ A. robustus” specimens have been found and only 5 percent of the 20,000-square-foot site ha been excavated. [Source: Andre Keyser, National Geographic, May 2000]

The two-million-year-old skull of a male Paranthropus robustus, dubbed DNH 155, has changed how scholars imagine one of our distant human cousins. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: P. robustus was thought to have been highly sexually dimorphic, meaning that males and females were drastically different in size and build. Paleoanthropologists had drawn that conclusion because the exclusively female skulls discovered at Drimolen Main Quarry were much smaller than those of male skulls discovered at nearby Swartkrans Cave, which date to 200,000 years later. But the male DNH 155 cranium, while somewhat larger than female skulls at Drimolen Main Quarry, is much smaller than P. robustus skulls from Swartkrans Cave. “DNH 155 is the final nail in the coffin for the sexual dimorphism hypothesis,” says La Trobe University anthropologist Jesse Martin, who co-led the team that discovered and analyzed the skull. The team now believes that the size difference between the P. robustus skulls at Drimolen Main Quarry and Swartkrans Cave resulted from adaptations to a changing environment over the few hundred thousand years that separated them. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021

Paranthropus robustus Skull and Body Features

Paranthropus robustus Skull Features: Massive jaw, no forehead and flat face with more prominent cheeks and less protruding jaw than earlier Australopithecus species. Sometimes called "ultimate chewing machine," it ate course, tough food such as nuts, hard-shelled fruits, fibrous tubers and roots.

Body Features: Ruggedly built and strong. The shape and organization of the hip and thigh indicate it was capable of bipedal movement. Hand bones indicate that its stout hand was capable of gripping stones in such as way as to make stone tools. Robustus have as many teeth as modern humans (32). The species had large, powerful teeth that had evolved to eat tough food such as tubers and bark.

Judging from the amount of wear, and knowing at what age certain teeth sprout in modern men, University of Pennsylvania scientists determined that most “robustus” died at the age of 17. Climates changes 2.5 million years ago caused drying and the resulting environmental changes produced coarser food. “A. robustus” developed large, powerful teeth to chew up rough foods like tubers, roots and seeds as opposed to softer food like fruit. Males developed such powerful jaws their jaw muscles were attached to the top of their head.

Paranthropus robustus Food, Sex, and Leopards

In a study published in December 2007 in the journal Science, a team led Charles Lockwood of University College London theorized that dominant male “A. robustus” may have had large harems like modern gorillas do today. Based on the study of 35 fossilized A. robustus” remains, researchers found that adult males were considerably larger than adult females, a relationship usually associated with a dominate male and harem relationship in other animals. As it true with dominant males in other animal species male “A. robustus” kept on growing even after reaching adulthood while females stopped growing when they reached breeding age.

An “A. robustus” skull was discovered in a South African cave with four holes in it. At first it was thought the holes were the result of a blow from a weapon, but later it was discovered they matched up perfectly with the teeth of a leopard also found in the cave. It appears that after the leopard killed the hominin it bit into its head piercing the skull with its teeth. Scientists speculate the leopard then dragged the early human into a tree where it could keep the kill away from scavengers such as hyenas. The skull later dropped from the tree and rolled into the cave. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, November 1985 [┹]

Many of the remains found in Drimolen cave are of are of juveniles and infants. Many are believed to have been prey of leopards or saber-toothed tigers that dragged their prey to the cave and it them like leopards do today with their prey in trees.

Paranthropus boisei (Australopithecus boisei, Nutcracker Man)

Paranthropus robustus Paranthropus boisei (also known as Australopithecus boisei) stood about 1.2 meters (4 feet tall) and had a small brain and a wide, dish-like face. It is most well-known for having big teeth and strong chewing muscles. Paranthropus boisei was first called Zinjanthropus boisei by its discoverer Dr. Louis Leakey but later was grouped with the Australopithecus genus. It is regarded as one of the first tool makers (See First Hominin Tools). Zinjanthropus means “East Africa Man.”

Geologic Age: 2.3 million to 1.4 million years. Lived at same as “Australopithecus robustus” and “Homo habilis”. (Time range includes specimens identified as Australopithecus aethiopicus). Size: Bigger than robustus. Males: 1.37 meters (4 foot 6 inches), 49 kilograms (108 pounds); females: 1.24 meters (4 foot 1 inches), 34 kilograms (75 pounds). Brain Size: About the same as robustus. “Linkage to Modern Man: “ Robustus and boisei may be different subspecies of a single, variable species. Believed to be an evolutionary dead end. Discovery Sites: In 1959 in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania by Mary Leakey, housed at the National Museum of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam. Remains have also been found in Omo in Ethiopia, Lake Turkana in Kenya, and Malema on Lake Malawi.

Skull Features: Molars and face even more massive than robustus, earned him the name "nutcracker man." Distinctive bony crest on the male skull anchored massive chewing muscles. The upper jaw and molars are the largest of any hominin species. Body Features: Powerful upper body.

'Nutcracker Man' Mostly Ate Grass

In 2011, AP reported, “Nutcracker Man didn't eat nuts after all. After a half-century of referring to an ancient pre-human as "Nutcracker Man" (Paranthropus boisei) because of his large teeth and powerful jaw, scientists now conclude that he actually chewed grasses instead. “The study "reminds us that in paleontology, things are not always as they seem," commented Peter S. Ungar, chairman of anthropology at the University of Arkansas. The report, by Thure E. Cerling of the University of Utah and colleagues, was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, Associated Press. May 3, 2011]

Cerling's team analyzed the carbon in the enamel of 24 teeth from 22 individuals who lived in East Africa between 1.4 million and 1.9 million years ago. One type of carbon is produced from tree leaves, nuts and fruit, another from grasses and grasslike plants called sedges. It turns out as Paranthropus boisei did not eat nuts but dined more heavily on grasses than any other human ancestor or human relative studied to date. Only an extinct species of grass-eating baboon ate more, they said. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the University of Colorado.

Paranthropus boisei "That was not at all what we were expecting," Cerling told AP. Scientists will need to rethink the ways our ancient relatives were using resources, he said. Added co-author Matt Sponheimer of the University of Colorado: "Frankly, we didn't expect to find the primate equivalent of a cow dangling from a remote twig of our family tree." A Paranthropus skull was discovered by Mary and Louis Leakey in 1959 at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, and helped put the Leakeys on the world stage. Their daughter-in-law, Maeve Leakey, is a co-author of the paper.

Cerling said much of the previous work on Nutcracker Man was based on the size, shape and wear of the teeth. His team analyzed bits of tooth removed with a drill and the results were completely different, Cerling said. "It stands to reason that other conclusions about other species also will require revisions," he said.Ungar, who was not part of the research team, suggested in 2007 the possibility that Nutcracker Man human ate grasses, based on tooth wear.

"The big, flat molars, heavily buttressed skull, and large, powerful chewing muscles of Paranthropus boisei scream 'nut cracker,' and that is exactly what this species has been called for more than half a century," he said via email. "But science demands that our interpretations be tested."With carbon analysis, the researchers take us "one step closer to understanding the diets of these fascinating hominins," Ungar said.

"This is a very important paper” because people have traditionally felt that the teeth of boisei were incapable of processing foods like grasses," added biology professor Mark Teaford of Johns Hopkins University. Cerling said it took some convincing to get the tooth samples for drilling from the National Museum of Kenya. "The sound of the drill may make a lot of paleontologists and museum staff cringe," co-author Kevin Uno, a doctoral student at Utah, said in a statement. But "it provides new information that we can't get at any other way."

‘Nutcracker Man’ Feasted On Tiger Nuts 2 Million Years Ago

In 2014, the University of Oxford reported: “An Oxford University study has concluded that our ancient ancestors who lived in East Africa between 2.4 million-1.4 million years ago survived mainly on a diet of tiger nuts. Tiger nuts are edible grass bulbs still eaten in parts of the world today. The study published in the journal, PLOS ONE, also suggests that these early hominins may have sought additional nourishment from fruits and invertebrates, like worms and grasshoppers. [Source: University of Oxford , January 9, 2014 ==]

“Study author Dr Gabriele Macho examined the diet of Paranthropus boisei, nicknamed “Nutcracker Man” because of his big flat molar teeth and powerful jaws, through studying modern-day baboons in Kenya. Her findings help to explain a puzzle that has vexed archaeologists for 50 years. ==

“Scholars have debated why this early human relative had such strong jaws, indicating a diet of hard foods like nuts, yet their teeth seemed to be made for consuming soft foods. Damage to the tooth enamel also indicated they had come into contact with an abrasive substance. Previous research using stable isotope analyses suggests the diet of these homimins was largely composed of C4 plants like grasses and sedges. However, a debate has raged over whether such high-fibre foods could ever be of sufficiently high quality for a large-brained, medium-sized hominin. ==

“Dr Macho’s study finds that baboons today eat large quantities of C4 tiger nuts, and this food would have contained sufficiently high amounts of minerals, vitamins, and the fatty acids that would have been particularly important for the hominin brain. Her finding is grounded in existing data that details the diet of year-old baboons in Amboseli National Park in Kenya — a similar environment to that once inhabited by Paranthropus boisei. Dr Macho’s study is based on the assumption that baboons intuitively select food according to their needs. She concludes that the nutritional demands of a hominin would have been quite similar. ==

Paranthropus robustus teeth “Dr Macho modified the findings of the previous study on baboons by Stuart Altmann (1998) on how long it took the year-old baboons to dig up tiger nuts and feed on various C4 sources. She calculated the likely time taken by hominins, suggesting that it would be at least twice that of the yearling baboons once their superior manual dexterity was taken into account. Dr Macho also factored in the likely calorie intake that would be needed by a big-brained human relative. ==

“Tiger nuts, which are rich in starches, are highly abrasive in an unheated state. Dr Macho suggests that hominins’ teeth suffered abrasion and wear and tear due to these starches. The study finds that baboons’ teeth have similar marks giving clues about their pattern of consumption. In order to digest the tiger nuts and allow the enzymes in the saliva to break down the starches, the hominins would need to chew the tiger nuts for a long time. All this chewing put considerable strain on the jaws and teeth, which explains why “Nutcracker Man” had such a distinctive cranial anatomy. The Oxford study calculates a hominin could extract sufficient nutrients from a tiger nut- based diet, i.e. around 10,000 kilojoules or 2,000 calories a day — or 80 percent of their required daily calorie intake, in two and half to three hours. This fits comfortably within the foraging time of five to six hours per day typical for a large-bodied primate. ==

“Dr Macho, from the School of Archaeology at Oxford University, said: ‘I believe that the theory — that “Nutcracker Man” lived on large amounts of tiger nuts- helps settle the debate about what our early human ancestor ate. On the basis of recent isotope results, these hominins appear to have survived on a diet of C4 foods, which suggests grasses and sedges. Yet these are not high quality foods. What this research tells us is that hominins were selective about the part of the grass that they ate, choosing the grass bulbs at the base of the grass blade as the mainstay of their diet. ‘Tiger nuts, still sold in health food shops as well as being widely used for grinding down and baking in many countries, would be relatively easy to find. They also provided a good source of nourishment for a medium-sized hominin with a large brain. This is why these hominins were able to survive for around one million years because they could successfully forage — even through periods of climatic change.’” ==

Paradox of the Nutcracker Man

Erin Wayman wrote in smithsonian.com: “It’s not hard to understand why Paranthropus boisei is often called the Nutcracker Man. The hominin’s massive molars and enormous jaw make it seem pretty obvious that the species spent a lot of time chomping on hard nuts and seeds. Yet, the only direct evidence of P. boisei‘s meals—the chemistry and microscopic scratches of the teeth—hint that the species probably didn’t crack nuts all that much, instead preferring the taste of grass. A team of anthropologists that recently reviewed the possible diets of several early hominin species has highlighted this paradox of the Nutcracker Man and the difficulties in reconstructing the diets of our ancient kin. [Source: Erin Wayman, smithsonian.com, June 25, 2012 |~|]

“The first place anthropologists start when analyzing diet is the size and shape of the hominin’s teeth and jaws. Then they look for modern primates that have similar-looking dentition to see what they eat. For example, monkeys that eat a lot of leaves have molars with sharp cusps for shearing the tough foliage. On the other hand, monkeys that eat a lot of fruit have low, rounded molar cusps. If you found a hominin with either of those traits, you’d have a starting point for what the species ate. |~|

“But the morphology of a species’ teeth and jaws only shows what the hominin was capable of eating, not necessarily what it typically ate. In some cases, these physical traits might reflect the fallback foods that a species relied on when its preferred foods were unavailable during certain times of the year. Frederick Grine of Stony Brook University in New York and colleagues point this out in their recent review in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. |~|

“Grine and colleagues note that other lines of evidence directly record what an individual ate. One method is to look at the chemistry of a tooth’s dental enamel. As the enamel forms, atoms that an individual consumes become incorporated in the tooth. One of the most common elements to look for is carbon. Because different plants have unique ratios of carbon isotopes based on how they undergo photosynthesis, the carbon isotopes act as a stamp that records what the individual once ate. Researchers look for two main plant groups: C3 plants are trees, fruits and herbaceous plants that grow in environments with cooler seasons while C4 plants are the grasses and sedges that grow in tropical, warm regions. Finding the isotopic traces of C3 or C4 plants in teeth indicate a hominin ate those plants (or animals that ate those plants). |~|

“Another way to directly sample diet is to look at the characteristic microscopic markings on a tooth’s surface that form when chewing certain foods. Eating tough grasses and tubers, for example, will leave behind scratches; hard nuts and seeds create pits. One drawback of this method is that a tooth’s microwear is constantly reshaped whenever an individual eats. So, the markings found by anthropologists probably represent an individual’s “last meal,” whatever he or she was eating in the days before death. If a hominin had a diet that changed seasonally, part of the diet may not be reflected in the tooth’s surface wear. |~|

“With all of these methods in mind, Grine and his colleagues considered the probable diets of several early hominin species. A comparison of the closely related P. bosei and Paranthropus robustus emphasized the puzzle of the Nutcracker Man. |~|

“P. robustus lived in South Africa 1.2 million to 1.8 million years ago when the region was an open grassland. The species’ giant, thickly enameled molars and premolars (better known as bicuspids) and heavy jaw suggest P. robustus was chewing hard objects. The surface wear on the teeth also point to eating hard foods and resemble the wear patterns seen in modern mangabey monkeys, which often eat nuts. The teeth’s enamel chemistry further supports this conclusion: As much as 60 percent of the species’ diet consisted of C3 plants, which would include hard-shelled nuts and fruits (carbon chemistry can’t detect which part of a plant an animal ate). |~|

“P. boisei lived in the wooded and open grasslands of East Africa at about the same time P. robustus was alive. It had an even larger jaw and teeth, with the biggest molars of any hominin. These traits indicate the species was a powerful chewer. But the wear patterns on the molar lack the deep pits that characterize those of hard-object eaters. Instead, the patterns match those of gelada baboons, which eat a lot of tough grasses. A grass diet is further hinted at by the carbon isotopes in P. boisei teeth: As much as 77 percent of their diet consisted of C4 plants (grasses and sedges). |~|

“Grine and his colleagues suggest there may be a way to reconcile the paradox of P. boisei. Instead of being adaptations to cracking open hard objects, the species’ massive teeth and jaws may have been traits that helped P. boisei handle very abrasive foods, including any grit clinging to blades of grass. Or perhaps the species’ used its giant molars to grind its food in a unique way. These are ideas that anthropologists should further investigate. Although P. boisei‘s diet seems puzzling, one thing is clear: The apparent mismatch between the various lines of evidence demonstrate that anthropologists still have a lot to learn about what our ancestors ate. |~|

Kenyanthropus Platyops

Kenyanthropus Platyops

Kenyanthropus Platyops (meaning "flat-faced Kenya man") is a hominin dated to be 3.5 million to 3.2 million years old. Living in ancient woodland, it had a small brain, flat face, vertical cheek bones, and small teeth and most likely consumed fruits, berries and insects with its small teeth. By contrast Australopithecus afarensis ate tougher items likes roots and grasses with its larger teeth. Only a cranium, jaw fragments and teeth were found, making it impossible to determine sex, size and age. [Source: National Geographic, October 2001]

Meave Leakey considered to Kenyanthropus Platyop” to be different enough from Australopithecus to place it on a separate evolutionary branch from Australopithecus afarensis. “Kenyanthropus Platyops” however has some similarities with “ Homo Rudolfensis” , which lived in east Africa between 2.4 million and 1.8 million years ago. "It spoils the easy straight-line picture of the past," she said. "We have to have to rethink the evidence."

“ Kenyanthropus Platyops” was discovered in 1999 at a site called Lomekwi on the western shore the Lake Turkana area of Kenya by a Justus Erus, a member of Meave Leakey's Hominin Gang. The discovery was made at the end of the fossil hunting season after Leakey's team had moved to a new areas around Lake Turkana. Erus noticed a white object, about an inch wide, sticking out of the brown mudstone. He first thought the bone he saw belonged to a monkey but Leakey knew immediately that it belonged to a hominin. It took several days to excavate all the bones and about a year and half to assemble them in a Nairobi lab into a mostly complete skull.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024

.JPG)

.JPG)