AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA CHARACTERISTICS

facial reconstruction of Australopithecus sediba

Australopithecus sediba, which means "southern ape, wellspring", lived some 2 million years ago. Discovered in 2008 by the nine-year-old son of paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand in a cave South Africa, it was good at climbing trees but also walked upright on the ground. Some scientists regard it as an the evolutionary link between the genus Homo, which includes modern humans, and the australopithecine, ape-like species that are believed to have preceded Homo.

The shape of the pelvis, hands and teeths in relatively human-like, but other characteristics are quite ape-like. Professor Berger said: 'They walk on two legs. They would probably only be standing about 1.3 metres tall. They also been more lightly built. They would've been quite skinny. 'They had longer arms than we do, more curved fingers. So, they're clearly climbing something. They also would've moved a little different. Their hips were slightly different than ours and their feet are slightly different. 'So, their gait would've probably been a more rolling type gait, slightly different from the more comfortable long distance stride we had. 'As they got closer to you, you'd be struck by for the most obvious thing which would be, their heads are tiny.' [Source: MailOnline, May 8, 2015]

According to MailOnline: “It has a narrow upper rib cage while the modern human's thorax is uniformly cylindrical. The cone-shaped rib cage allowed the early hominin to move its shoulder blades so it could climb trees. However, this prevented A. sediba from swinging its arms, meaning that walking and running was much more difficult. It had a slim waist similar to modern humans but feet which turned sharply inwards. A. sediba had the same number of lumbar vertebrae as a modern humans and a similar curvature of the lower back. However, its back was longer and more flexible than that of modern humans. They had longer arms than we do with curved fingers, which would have made them adept at climbing. [Source: MailOnline, May 8, 2015]

According to Archaeology magazine: Australopithicus sediba, differed from other australopiths in its poor ability to bite down on hard foods. Biomechanical tests using a digital model of an A. sediba skull, found in 2008, determined that if A. sediba bit down with all the force of its chewing muscles, it would dislocate its jaw — just like humans, but unlike other australopiths. While this is not proof that A. sediba evolved into modern humans, it does suggest that diet may have played a strong role in human evolution. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

See Separate Article: AUSTRALOPITHECUS SEDIBA: DISCOVERY SITE AND SIGNIFICANCE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cave of Bones” by Lee Berger (2023) Amazon.com;

“Almost Human: The Astonishing Tale of Homo Naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story” by Lee Berger, John Hawks, et al. Amazon.com;

“A Handbook to the Cradle of Humankind” by Marina C. Elliott and Lee R. Berger Amazon.com;

“Lucy: the Beginnings of Humankind” by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey (1981) Amazon.com;

“Lucy's Legacy: The Quest for Human Origins” by Dr Donald Johanson and Kate Wong (2009) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Born in Africa: “The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

Australopithecus Sediba: a Confusing Mix of Human and Ape-like Traits

Lucy in the middle compared to Australopithecus Sediba

Six papers published online by Science in 2013 after the the initial examination of two partial skeletons and an isolated shinbone of Australopithecus sediba continued to draw on the theme that A. sediba was a mix of human and more apelike characteristics. Jeremy DeSilva of Boston University, lead author of one of the papers, said the fossils reveal an unexpected "mosaic of anatomies." "I didn't think you could have this combination, that hand with that pelvis with that foot... And yet, there it is," he said. Dr DeSilva said he has no idea how A. sediba is related to humans, noting that the different traits argue for different conclusions [Source: Malcolm Ritter, Associated Press, April 12, 2013 /*/]

Malcolm Ritter of Associated Press wrote: “Among the new analyses, the ribs show the creature's upper trunk resembled an ape's, while the lower part looked more like a human's. Arm bones other than the hand and wrist look primitive, reflecting climbing ability, while earlier analysis of the hand had shown mixed traits. The teeth also show a mix of human and primitive features, and provide new evidence that A. sediba is closely related to early humans, said Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg of Ohio State University, a co-author of a dental analysis. It and an older South African species, A. africanus, appear more closely related to early humans than other australopithecines like the famous "Lucy" are, she said. But she said the analysis can't determine which of the two species is the closer relative, nor whether A. sediba is a direct ancestor of humans.” /*/

Unusual Mix of Primitive and Advanced Features in Australopithecus sediba

In September 2011, LiveScience.com reported: “A startling mix of human and primitive traits found in the brains, hips, feet and hands of Australopithecus sediba make a strong case for it being the immediate ancestor to the human lineage, scientists have announced. These new findings could rewrite long-standing theories about the precise steps human evolution took, they added, including the notion that early human female hips changed shape to accommodate larger-brained offspring. There is also new evidence suggesting that this species had the hands of a toolmaker. The scientists detailed their findings in the Sept. 9 2011 issue of the journal Science.

The heel bone seems primitive, the researchers said. Yet its front is angled, suggesting an arched foot for walking on the ground, and there is a large attachment for an Achilles tendon as in modern humans, they said. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, AP, September 8 2011]

The pelvis is short and broad like a human pelvis, creating more of a bowl shape than in earlier australopith fossils like the famous Lucy, explained Job Kibii of the University of the Witwatersrand. That find may force a re-evaluation of the process of evolution because many researchers had previously associated development of a humanlike pelvis with enlargement of the brain, but in A. sediba the brain was still small.

The subjects of the research were the bones of an adult female and a child. After the discovery, the children of South Africa were invited to name the child, which they called "Karabo," meaning "answer" in the local Tswana language. The older skeleton has not yet been given a nickname, Berger said. The juvenile would have been aged 10 to 13 in terms of human development; the female was in her 20s and there are indications that she may have given birth once. The researchers are not sure if the two were related.

Australopithecus sediba Brain

Kristian J. Carlson, a paleoanthropologist at Witwatersrand Wits who is reconstructing A. sediba's brain, told AP, the brain of A. sediba is small — 420 cubic centimeters — like that of a chimpanzee, but with a configuration more human, particularly with an expansion behind and above the eyes.This seems to be evidence that the brain was reorganizing along more modern lines before it began its expansion to the current larger size, Carlson said in a teleconference."It will take a lot of scrutiny of the papers and of the fossils by more and more researchers over the coming months and years, but these analyses could well be 'game-changers' in understanding human evolution," according to the Smithsonian's Potts. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, AP, September 8 2011]

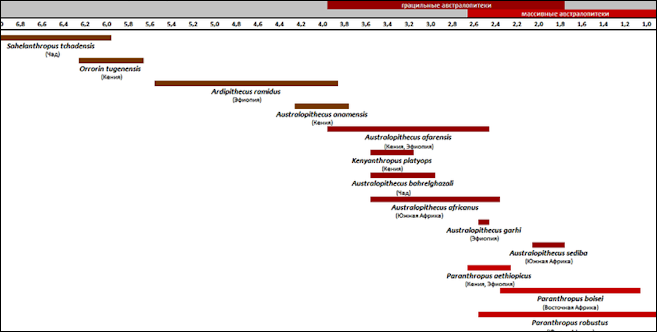

comparison of when Austalopithecines lived

"The frontal lobes on the two halves appear to be different sizes," Carlson told National Geographic. Pronounced asymmetry between right and left brain hemispheres is a hallmark of humans, because our cerebrum has become specialized, with the left side more involved in language. On that side Carlson sees hints of a protrusion in the region of Broca's area---a part of the brain linked to language processing in modern humans. But Dean Falk from the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, an expert on fossil endocasts, adds the caution that Broca's area is defined by specific creases in the brain, and "it would be quite a reach" to identify it based only on a bulge. [Source: Josh Fischman, National Geographic , August 2011]

"The fossils demonstrate a surprisingly advanced but small brain, a very evolved hand with a long thumb like a human's, a very modern pelvis, but a foot and ankle shape never seen in any hominin species that combines features of both apes and humans in one anatomical package," Berger said. "The many very advanced features found in the brain and body and the earlier date make it possibly the best candidate ancestor for our genus, the genus Homo, more so than previous discoveries such as Homo habilis." [LiveScience.com, September 2011]

The juvenile specimen of Au. sediba had an exceptionally well-preserved skull that could shed light on the pace of brain evolution in early hominins. To find out more, the researchers scanned the space in the skull where its brain would have been using the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France; the result is the most accurate scan ever produced for an early human ancestor, with a level of detail of up to 90 microns, or just below the size of a human hair. The series of ultrahigh-resolution images create a virtual endocast: an impression of the boy's skull showing the general contours of the outer brain layer.

The scan revealed Au. sediba had a much smaller brain than seen in human species, with an adult version maybe only as large as a medium-size grapefruit. However, it was humanlike in several ways---for instance, its orbitofrontal region directly behind the eyes apparently expanded in ways that make it more like a human's frontal lobe in shape. This area is linked in humans with higher mental functions such as multitasking, an ability that may contribute to human capacities for long-term planning and innovative behavior. "We could be seeing the beginnings of those capabilities," researcher Kristian Carlson at the University of Witwatersrand told LiveScience.

These new findings cast doubt on the long-standing theory that brains gradually increased in size and complexity from Australopithecus to Homo. Instead, their findings corroborate an alternative idea---that Australopithecus brains did increase in complexity gradually, becoming more like Homo, and later increased in size relatively quickly.

Evidence of arched feet have been found in Australopithecus sediba. Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: The study of A. sediba feet, part of a new comprehensive analysis of the skeletal remains, shows a human-looking ankle, Achilles tendon, and arch, but also ape-like features more adapted for climbing trees.[Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology Volume 64 Number 6, November/December 2011]

comparison of homini brain and tooth size

Australopithecus Sediba Primarily Ate Bark, Wood and Leaves

Based on marks left on the teeth two specimens found in Malapa caves in southern Africa, it appears that Australopithecus sediba, subsisted almost entirely on a diet of leaves, fruits, wood and bark, a finding that contrasted sharply with the known diet of other hominins in the region and time frame, who mainly consumed grasses and sedges from the savanna. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, June 27, 2012 ]

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times: “The Au. sediba diet also appeared to be a matter of choice, not necessity. Other evidence from animal fossils and sediments in the area indicated the presence at the time of vast grasslands in the vicinity. Yet these hominins, their skeletons adapted for tree climbing as well as upright walking, chose to feed themselves in adjacent woodlands. In this, scientists said, their behavior was more like that of modern chimpanzees, which tend to ignore savanna grasses, or perhaps the more apelike hominin Ardipithecus ramidus, which lived largely on hard foods some 4.4 million years ago.”

“An international team of scientists led by Amanda G. Henry of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, reported on the research that supported their findings in the journal Nature. “If these individuals are representative of the species,” the scientists wrote, “Au. sediba had a diet that was different from those of most early African hominins studied so far.” They also concluded that the “inferred consumption” of woodland products “increased the known variety of early hominin foods.” But there is still much that is unknown or unclear about the newfound species: how or if it is related to modern humans and just where it fits on the hominin family tree.

“Ian Tattersall, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, who was not involved in the research, called the findings “intriguing” and the research “an imaginative and multisided approach that makes you want to know more about this morphologically unusual species.” “Fortunately,” Dr. Tattersall added, “rumor has it that more specimens are on the way.”

“Dr. Henry’s team followed three lines of research. One was an analysis of carbon isotopes extracted by laser from tooth enamel, one of the most durable and least contaminated body parts, and one that preserves chemical signatures of what was eaten in one’s youth. The type and amount of isotopes left from a diet of tree leaves, fruit and bark were well outside the range of those seen in all previously tested hominins — at least 95 percent forest food.

“A second approach was an examination of dental microwear, which can reveal pits, scratches and cracks left by hard foods consumed shortly before death. Dr. Tattersall said that this “doesn’t help much to clarify the situation, since it appears to differ significantly between the two individuals.” Finally, microscopic plant particles, called phytoliths, were recovered from dental tartar for the first time from a very ancient hominin (but from only one of the two individuals). Scientists said this apparently confirmed the carbon isotopic evidence for woodland diets.

“Benjamin H. Passey, a geochemist at Johns Hopkins University, who conducted the tests determining the high ratio of carbon isotopes indicating a diet mostly of forest foods, explained why the research was important to an understanding of human evolution. “One thing people probably don’t realize is that humans are basically grass eaters,” Dr. Passey said in a statement. “We eat grass in the form of the grains we use to make breads, noodles, cereals and beers, and we eat animals that eat grass. So when did our addiction to grass begin? At what point in our evolutionary history did we start making use of grasses? We are simply trying to find out where in the human chain that begins.”“

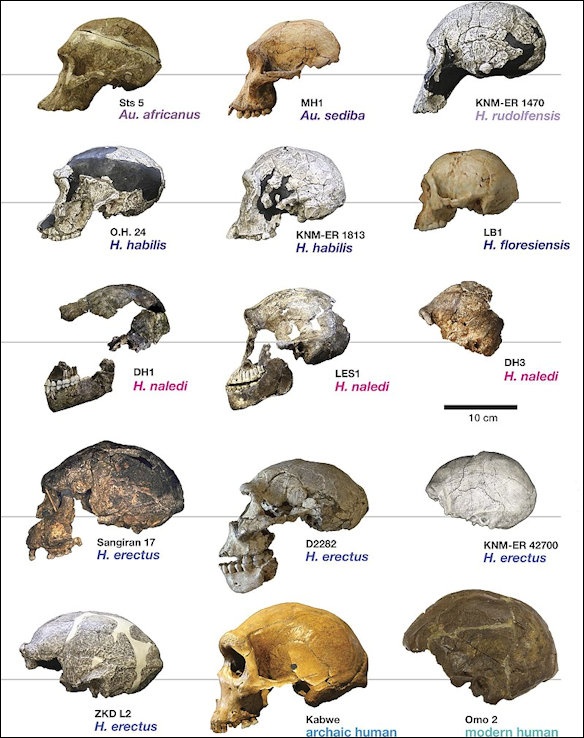

comparison of hominin skulls

Scientists believe they have found the remains of seeds and other food particles stuck between Australopithecus sediba’s teeth. Professor Berger, said: 'We found out this wasn't just a normal type of rock that they were contained in - it was a rock that was preserving organic material. 'Plant remains are captured in it - seeds, things like that - even food particulates that are captured in the teeth, so we can see what they were eating. [Source: Richard Gray, MailOnline, May 8, 2015 ^=^]

Richard Gray wrote in MailOnline: The remains of plants and insects have also been found preserved in the cement-like breccia alongside the skeletons. It is thought that sediment in the bottom of a pool of water may have helped to protect the organic material from bacteria that would have caused them to rot and break down. ^=^

Australopithecus sediba Hips and Feet

In September 2011, LiveScience.com reported: “An analysis of the partial pelvis of the female Au. sediba revealed that it had modern, humanlike features. "It is surprising to discover such an advanced pelvis in such a small-brained creature," said researcher Job Kibii at the University of the Witwatersrand. "It is short and broad like a human pelvis ... parts of the pelvis are indistinguishable from that of humans." [LiveScience.com, September 2011]

Scientists had thought the human-like pelvis evolved to accommodate larger-brained offspring. The new findings of humanlike hips in Au. sediba despite small-brained offspring suggests these pelvises may have instead initially evolved to help this hominin better wander across the landscape, perhaps as grasslands began to expand across its habitat.

When it came to walking, investigating the feet and ankles of the fossils revealed surprises about how Au. sediba might have strode across the world. No hominin ankle has ever been described with so many primitive and advanced features. "If the bones had not been found stuck together, the team may have described them as belonging to different species," said researcher Bernhard Zipfel at the University of the Witwatersrand.

The researchers discovered that its ankle joint is mostly like a human's, with some evidence for a humanlike arch and a well — efined Achilles tendon, but its heel and shin bones appear to be mostly ape-like. This suggested the hominin probably climbed trees yet also halkid in a unique way not exactly like that of humans. Altogether, such anatomical traits would have allowed Au. sediba to walk in perhaps a more energy-efficient way, with tendons storing energy and returning that energy to the next step, said researcher Steve Churchill from Duke University in Durham, N.C. "These are the kinds of things that we see with the genus Homo," he explained.

Australopithecus Sediba’s Unusual Walking Style

ankles bones of Australopithecus sediba

One study of Australopithecus sediba’s leg bones concluded that it walked like no other known animal. Malcolm Ritter of Associated Press wrote: “ Its heel was narrow like an ape's, which would seem to prevent walking upright, but the more humanlike knee, pelvis and hip show A. sediba did just that, anthropologist Jeremy DeSilva of Boston University said. When people walk, they strike the ground with the heel first. But that would be disastrous from A. sediba's narrow heel bone, so instead the creature struck the ground first with the outside of the foot, Dr DeSilva and co-authors propose. The foot would react by rolling inward, which is called pronation. In people, chronic pronation can cause pain in the foot, knees, hip and back, said Dr DeSilva, who tried out the ancient creature's gait. "I've been walking around campus this way, and it hurts," he said. But the bones of A. sediba show features that evidently prevented those pain problems, he said. The creature apparently adopted this gait as a kind of compromise for a body that had to climb trees proficiently as well as walk upright, he said. [Source: Malcolm Ritter, Associated Press, April 12, 2013].

Boston University reported: “Our Australopithecus ancestors may have used different approaches to getting around on two feet. The new findings, co-authored by Boston University researchers Jeremy DeSilva , assistant professor of anthropology, and Kenneth Holt, assistant professor of physical therapy, appear in the latest issue of the journal Science in an article titled "The Lower Limb and Mechanics of Walking in Australopithecus sediba." The paper is one of six published this week in Science that represent the culmination of more than four years of research into the anatomy of Australopithecus sediba (Au. sediba). The two-million-year-old fossils, discovered in Malapa cave in South Africa in 2008, are some of the most complete early human ancestral remains ever discovered. [Source: Boston University, Science Daily, April 11, 2013 /~]

“The locomotion findings are based on two Malapa Au. sediba skeletons. The relatively complete skeletons of an adult female and juvenile male made possible a detailed locomotor analysis, which was used to form a comprehensive picture of how this early human ancestor walked around its world. The researchers hypothesize this species walked with a fully extended leg (like humans do), but with an inverted foot (like an ape), producing hyperpronation of the foot and excessive rotation of the knee and hip during bipedal walking. These bipedal mechanics are different from those often reconstructed for other australopiths and suggest that there may have been several forms of bipedalism throughout human evolution. /~\

“Australopithecus sediba has a combination of primitive and derived features in the hand, upper limb, thorax, spine, and foot. It also has a relatively small brain, a human-like pelvis, and a mosaic of Homo- and Australopithecus-like craniodental anatomy. The foot in particular possesses an anatomical mosaic not present in either Au. afarensis or Au. africanus, supporting the contention that there were multiple forms of bipedal locomotion in the Plio-Pleistocene. (The recent discovery of an Ardipithecus-like foot from 3.4-million-year-old deposits at Burtele, Ethiopia, further shows that at least two different forms of bipedalism coexisted in the Pliocene.)

"Our interpretation of the Malapa skeletal morphology extends the variation in Australopithecus locomotion," says DeSilva. "As others have suggested, there were different kinematic solutions for being a bipedal hominin in the Plio-Pleistocene. The mode of locomotion suggested by the Malapa skeletons indicates a compromise between an animal that is adapted for extended knee bipedalism and one that either still had an arboreal component or had re-evolved a more arboreal lifestyle from a more terrestrial ancestor." DeSilva adds that there is some evidence that the South African species Au. africanus may have been more arboreal than the east African Au. afarensis. "A hypothesized close relationship between Au. africanus and Au. sediba, along with features in the upper limbs of the latter thought to reflect adaptations to climbing and suspension, is consistent with a retained arboreal component in the locomotor repertoire of Au. sediba."

Co-authors of this study are Kristian J. Carlson, Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN; Christopher S. Walker, Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC; Bernhard Zipfel, Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, , South Africa; and Lee R. Berger, Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Australopithecus sediba Hands

In September 2011, LiveScience.com reported: “An analysis of Au. sediba's hands suggests it might have been a toolmaker. The fossils — including the most complete hand known in an early hominin, which is missing only a few bones and belonged to the mature female specimen — showed its hand was capable of the strong grasping needed for tree-climbing, but that it also had a long thumb and short fingers. These would have allowed it a precision grip useful for tools, one involving just the thumb and fingers, where the palm does not play an active part. [LiveScience.com, September 2011]

One hand specimen lacks three wrist bones and four terminal phalanges but is otherwise complete. Altogether, the hand of Au. sediba has more features related to tool-making than that of the first human species thought of as a tool user, the "handy man" Homo habilis, said researcher Tracy Kivell at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. "This suggests to us that sediba may also have been a toolmaker." Though the scientists haven't excavated the site in search of stone tools, "the hand and brain morphology suggest that Au. sediba may have had the capacity to manufacture and use complex tools," Kivell added.

The researchers do caution that although they suggest that Au. sediba was ancestral to the human lineage, all these apparent resemblances between it and us could just be coincidences, with this extinct species evolving similar traits to our lineages due, perhaps, to similar circumstances.

In fact, it might be just as interesting to imagine that Au. sediba was not directly ancestral to Homo, because it opens up the possibility "of independent evolution of the same sorts of features," Carlson said. "Whether or not it's on the same lineage as leading to Homo, I think there are interesting questions and implications."

The fossil provides the first chance for researchers to evaluate the function of a full hand this old, Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, told AP. Previously, hand bones older than Neanderthals have been isolated pieces rather that full sets. The researchers reported that the fingers of A. sediba were curved, as might be seen in a creature that climbed in trees. But they were also slim and the thumb was long, more like a Homo thumb, so the hand was potentially capable of using tools. No tools were found at the site, however.

Australopithecus Sediba Skin?

Mathew Berger, Australopithecus sediba discoverer

Richard Gray wrote in MailOnline: “South African anthropologists believe they have found preserved skin from Australopithecus sediba. It could be the oldest soft tissue ever found for an early human species On two fragments of hominid skull excavated from the ground Professor Berger and his team noticed an unusual surface. Embedded in the cemented rock, known as breccia, that surrounded the cranial remains of the original fossil and a second found at the site were some small, thin layers that looked like preserved soft tissue. [Source: Richard Gray, MailOnline, May 8, 2015 ^=^]

“Professor John Hawks, an anthrolpologist at the University of Wisconsin Madison who is helping lead the project, said: 'They do not appear to be skin impressions within the matrix, they appear to be thin layers that are a different substance from the surrounding matrix. 'In the initial CT-scanning of the MH1 cranium, team members noticed an area where the matrix surrounding the skull appeared irregular. 'As they prepared this out, it became clear that the breccia itself had pulled away from the cranium across a small region, and the breccia had a thin layer of material at its surface there. 'This is not the outer table of the bone - which is intact in the corresponding area - nor is it apparently an impression of the bone. ^=^

“The team have been using 3D scanning, microscopy and chemical analysis in an attempt to examine the samples. The researchers also hope to find out whether, if it is soft tissue, it had been dried or soaked in water as it was preserved in the rock. 'An additional section of possible soft tissue emerged as the female MH 2 mandible was prepared. 'Upon magnification, these pieces do appear to have a structure.'^=^

Researching Australopithecus Sediba Skin?

Mineral deposits found on the fossilized remains of Australopithecus sediba could be early human skin. Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology: Scans of some of the fossils of the 2.2-million-year-old fossils of Australopithecus sediba “have revealed a thin layer of minerals that could be the remains of Australopithecus skin. To determine whether this is the case,Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and lead researcher on the project, is taking a revolutionary step and making this research project open source. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 1, January/February 2012]

“Berger has enlisted John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist and blogger at the University of Wisconsin, to reach out to the online scientific community for input on how the research should be designed and to help analyze the “skin” samples. Because no one has ever found fossilized early hominin skin, Hawks says, there are no experts on the subject.

“According to Hawks, the open-source approach will help the team avoid a common pitfall of early hominin research—the sometimes decades-long delay between a fossil’s discovery and the publication of scientists’ analysis of the find. The team will post project updates online to inform the community of its progress and address any issues that might arise before submitting the research to a peer-reviewed journal.

The project is starting to attract interest worldwide. Berger’s team is in discussions with Russian anthropologists who suggested comparing the Malapa samples to other specimens of fossilized skin. The team is also working with a mineralogist from the University of Oslo, in Norway, to find a way to examine the structure of the “skin” with an electron microscope. If the mineral layer does turn out to be preserved skin, it could provide information about A. sediba’s hair, pigmentation, and sweat glands. If the layer turns out to be something else, paleoanthropology may still have gained a new approach to research.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024