MALARIA MEDICINES AND PREVENTIVE MEASURES

malaria drugs given out

in Italy in the 1950s There are three basic forms of anti-malarial drugs: 1) suppresives, which eradicate malaria in the bloodstream; and 2) "casuals," which destroy the liver-stage merozites before the parasite reaches the bloodstream. Quinine, chloroquine, mefloquine and antibiotics such as doxycycline and tetracycline are all suppressives. They must be taken before and after visiting a malaria-infected area to make sure all liver-stage cells have hatched and been destroyed. 3) Artemisinin-based combination drugs, known as ACTs, work best but are more expensive (See Artemisinin Below). Artemether is one of the most effective drugs in the artemisinin group most commonly used in malaria cocktails known as ACTs.

Long-term use antimalarial drugs can cause side effects such as hearing loss, hair loss and liver and kidney damage. Since malaria medication is toxic if it is taken more than several months, local people usually don’t take them and take precautions against be bitten by mosquitos instead.

People who spend a lot of time in places where malaria is endemic have different strategies to tackle the disease. Some take medication. Some don’t take medication and rely on being very thorough meticulous about their anti-mosquito measures. Others wait until they come down with the disease and then start taking medication. Many sophisticated European travelers who dislike the side effect of preventive malaria medication carry Coartem — to treat themselves if they get malaria — and a finger-prick test kit to test if they have malaria.

The drug companies have traditionally not given a high a priority to anti-malaria drugs. Of the 1,223 new drugs approved between 1975 and 1996, only three were antimalarials. Many anti-malaria drugs sold overseas are counterfeits. A study by the journal Tropical Medicine & International found that 53 percent of the anti-malarials sold in five Asian countries were fake.

See Separate Articles:VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES CAUSED BY MOSQUITOES, TICKS AND FLIES factsanddetails.com; MOSQUITOES factsanddetails.com DENGUE FEVER factsanddetails.com; MALARIA: ITS HISTORY, PARASITE AND ITS LIFE-CYCLE factsanddetails.com; COMBATING MALARIA: NETS, DIRTY SOCKS, DNA AND VACCINE EFFORTS factsanddetails.com; MALARIA ERADICATION AND DDT factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions ; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets who.int/news-room/fact-sheets ; National Institute of Health (NIH) Library Medline Plus medlineplus/healthtopics ; Merck Manuals (detailed info many diseases) merckmanuals.com/professional/index ; Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria theglobalfund.org Book: “The Fever: How Malaria Has Ruled Humankind for 500,000 years” by Sonia Shah (2010, Sarah Crichton Books, Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Malaria Treatment and Testing

drug given at Myanmar refugee camp Malaria is diagnosed by examining a blood sample for the protozoa. Treatment is fairly easy in the early courses of the disease but is more difficult once the protozoa multiples and the infection really takes hold. The usual treatment is large doses of chloroquine even though the drug doesn’t work up to 80 percent of the time. Treatments with Fansidar are also often ineffective. Chloroquine and Fansidar remain popular because although they don’t cure the disease they temporarily lower the fever associated with it. Artemisinin-based combination drugs, known as ACTs, work best but are more expensive.

Rapid diagnostic tests are available that can detect malaria in a finger stick drop of blood. In the past much of the diagnosis was done by technicians looking through a microscope, which requires looking carefully at a smear of blood on a slide for some time until the parasites can be located.

The WHO recommends that all suspected cases of malaria be confirmed by a quick and cheap diagnostic test before antimalarial drugs are taken — rather than assuming any person with a fever has the mosquito-borne parasitic infection. This cuts down the over-prescribing of artemisinin-based ACTs, and slows the spread of resistance to them — which it fears could emerge in Africa. [Source: Stephanie Nebehay, Reuters, December 14, 2010]

One problem with malaria treatments is that many patients quit taking their medicine after their fever drops and never complete a full treatment. This allows the parasite to live on inside the body and increases its resistance to treatment. In the old days and in places where ACT drugs are not available, to cure malaria, patients are supposed to take 15 chloroquine pills over three days. People often bought one pill a day from a street a vendor and never finished the treatment. This treatment temporarily makes them feel better but it doesn’t cure their malaria or help them build up resistance to the disease.

People prepared to treat themselves if they get malaria bring along a single dose of three tablets of Fansidar, taken after the onset of the, disease or double dose of six Fansidar tablets (an initial dose of four tablets followed by two tablets of the next day ). Fansidar is only a temporary measure. People who take it should continue taking chloroquine and seek proper medical help immediately. Sulfidoxine and pryimethamine (Fansidar) is the second most widely used treatment. Like chloriquine it too is often ineffective.

Artemisinin

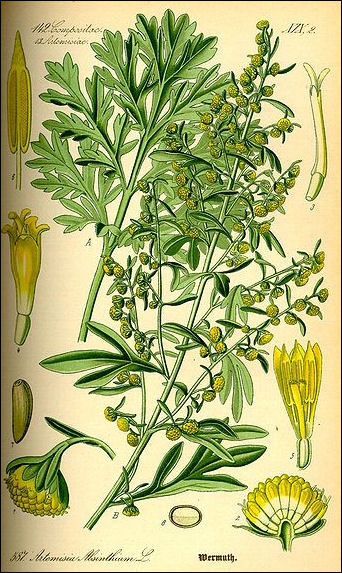

Artemisia absinthium Artemisinin is a powerful anti-malaria drug made from Artemisia annua, a plant also known as qinghao, qing hao or sweet wormwood that is native to southern China. Developed by Chinese scientists, it is the most effective new malaria treatment, curing 90 percent patients in three days with no significant side effects.

The Chinese first synthesized artemisinin in 1979. They had given the qinq hao plant to the Vietnamese who used it when they were fighting the Americans in the Vietnam War. The West first became aware of artemisinin in 1985 when Science published an article that described the drug’s success treating several thousand Chinese malaria sufferers.

Artemisinin began to displace chloroqine as the preferred drug for malaria treatment in the mid 2000s after the results were released from the controversial SEAQUAMAT (Southeast Asia Quinine Artesunate Malarial Trial) of June 2003 to May 2005. In the largest ever real-life trial for severe malaria , 2,000 participants in Bangladesh, Myanmar and Indonesia were split into two groups with half of them given quinine and half artemisinin. The study was stopped early because of the huge difference in morality between the two groups. Twenty-two percent of those in the quinine group died while 15 percent in artemisinin did. Arjen Dondorp of Mahidol University in Thailand, a leader of the study, told Reuters, “Artemisinin is better than quinine in all subgroups of patients with severe malaria. Artemisinin is the treatment of choice for severe malaria.”

The main draw backs of artemisinin are its costs ($1.30 per dose compared to $.25 for chloroquine) and the fact it is most effective when used with other anti-malarials. WHO officials worry that careless marketing of the drug a cheap, one-stop, non-prescription malaria panacea and use of artemisinin without the other cocktail drugs could create incurable strains of malaria immune to all malaria medicines.

Artemisia Annua

Artemisinin a comes from Artemisia annua, , also known as qinghao and sweet wormwood, a six-foot-tall plant with fernlike leaves that grows in China and Vietnam and originated from the Luofushan area of Guangdong Province in southern China. If it wasn’t for its fresh, sharp scent it would be easy to mistake Artemisia annua for any other shrub. No one knows how Artemisia annua it was first discovered. It was prescribed as hemorrhoid treatment in the 2nd century B.C. medical treatise “Fifty-Two Remedies” and described by Ge Heng (283-363), a Taoist priest preoccupied with the search for elixirs of immortality. In his "Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments," Ge wrote that patients suffering from high fever are advised to “take a handful of sweet wormwood, soak it in a sheng [about 1 liter] of water, squeeze the juice and drink it all.”

During the Vietnam War, the Chinese launched a secret military project to help the Vietcong combat malaria. The disease accounted for roughly half their casualties. Western health researchers were also trying to solve this problem, screening more than 200,000 compounds. Claire Panosian Dunavan wrote in Discover magazine: “Charged with finding a new remedy for malaria, scientists working for Mao Tse-tung and Chou En-lai decided to test Ge Hang’s ancient wormwood recipe in mice infected with a malarial strain that is lethal in rodents. In these experiments, the botanical tea performed as well as chloroquine and quinine. The researchers then isolated A. annua’s active ingredient (a crystalline compound called qinghaosu, or in chemical registries, artemisinin) and tested it in humans. In 1979 they finally published their findings in the Chinese Medical Journal. The news caused barely a ripple until a 1985 Science article confirmed that qinghaosu had successfully treated several thousand Chinese malaria sufferers. Artemisinin’s water-soluble derivative, artesunate, appeared to be more promising. Studies showed that patients comatose from cerebral malaria were restored to consciousness. [Source: Claire Panosian Dunavan, Discover magazine, August 2005]

Artemisia annua has become a major cash crop in places like Zhuoshui along the Apeng River in the southern Chongqing area of central China. Farmers that used to eek out a living growing corn are now making a small fortune raising qinghao in their fields or collected it on mountainsides.

How Artemisinin Works

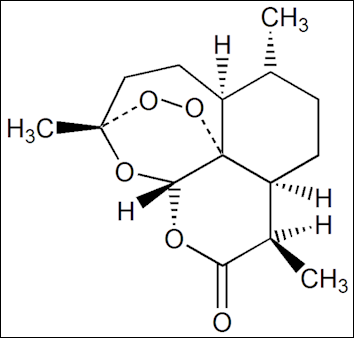

Artemisinin Artemisinin is used against the falciaparum strain of malaria. It acts very quickly, reducing the parasite’s biomass in the human body, and is particularly effective at destroying drug-resistant malarial parasites in the bloodstream. Artemisinin works like many anti-malaria drugs by attacking the malaria parasite’s sexual stage of its life cycle, preventing the multiplication of parasites that fuels the infection.

The drug also gets rid of the asexual forms of the parasite faster than any known treatment. The main chemical feature of artemisinin is an unstable bond between two oxygen atoms that generates free radicals that break up proteins in the protozoa. The release occurs upon exposure to Hemozoin, the dark granular digest of hemoglobin that accumulates in plasmodium-infected blood cells.

Artenisinin disrupts the transfer of the parasite from humans to mosquitoes. Because it throws off the whole malaria cycle it also holds great promise eradicating malaria from areas where it used.

Artemisinin works very fast, which is mostly a good thing but the downside is that the drug dissipates quickly in the bloodstream and patients need to take it for seven days to allow it to do its thing. But if artemisinin is combined with another drug such as mefloquin the course can be reduced to three days. The two-drug cocktail also offers protection from future resistance to artemisinin. The cost of these treatments is about $2 a course, considerably more expensive than 10 cents for chloroquine. The cost of some artemisinin-based drugs is about $1 per treatment.

Tu Youyou, Artemisinin Discover and Nobel Prize Winner

The discovery of artemisinin won Chinese scientist Tu Youyou a Nobel Prize in medicine 2015. She become the first Chinese woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first citizen of the People’s Republic of China to win it in something other than literature or peace. The BBC reported: The 84-year-old's route to the honour has been anything but traditional. She doesn't have a medical degree or a PhD. She attended a pharmacology school in Beijing and became a researcher at the Academy of Chinese Traditional Medicine. In China, she is being called the "three noes" winner: no medical degree, no doctorate, and she's never worked overseas. [Source: Celia Hatton, BBC News, October 6, 2015]

“She started her malaria research after she was recruited to a top-secret government unit known as "Mission 523". In 1967, Communist leader Mao Zedong decided there was an urgent national need to find a cure for malaria. At the time, malaria spread by mosquitoes was decimating Chinese soldiers fighting Americans in the jungles of northern Vietnam. A secret research unit was formed to find a cure for the illness.

finger prick detection

“Two years later, Tu Youyou was instructed to become the new head of Mission 523. She was dispatched to the southern Chinese island of Hainan to study how malaria threatened human health. For six months, she stayed there, leaving her four-year-old daughter at a local nursery.

Ms Tu's husband had been sent away to work at the countryside at the height of China's Cultural Revolution, a time of extreme political upheaval.

Ancient Chinese texts inspired Tu Youyou's search for her Nobel-prize winning medicine Mission 523 pored over ancient books to find historical methods of fighting malaria. When she started her search for an anti-malarial drug, over 240,000 compounds around the world had already been tested, without any success. Finally, the team found a brief reference to one substance, sweet wormwood, which had been used to treat malaria in China around 400 AD.

“The team isolated one active compound in wormwood, artemsinin, which appeared to battle malaria-friendly parasites. The team then tested extracts of the compound but nothing was effective in eradicating the drug until Tu Youyou returned to the original ancient text. After another careful reading, she tweaked the drug recipe one final time, heating the extract without allowing it to reach boiling point.

“After the drug showed promising results in mice and monkeys, Tu Youyou volunteered to be the first human recipient of the new drug. “As the head of the research group, I had the responsibility," she explained to the Chinese media. Shortly after, clinical trials began using Chinese labourers.

“Tu Youyou is typically described in China as a "modest" woman. Her work was published anonymously in 1977, and for decades she received little recognition for her research with Mission 523. In 2009, Ms Tu published an autobiography looking back on her scientific career. However, she was quickly attacked by some for claiming the spotlight while seemingly ignoring contributions from her colleagues.

“Some allege that two other researchers had already targeted the compounds in sweet wormwood before Tu Youyou joined Mission 523. However, she was the one who allegedly consulted the ancient text to study how best to extract the compound for use in medicine. In any case, Tu Youyou is consistently cited for her drive and passion. One former colleague, Lianda Li, says Ms Tu is "unsociable and quite straightforward", adding that "if she disagrees with something, she will say it".

“Another colleague, Fuming Liao, who has worked with Tu Youyou for more than 40 years, describes her as a "tough and stubborn woman". Stubborn enough to spend decades piecing together ancient texts and apply them to modern scientific practices. The result has saved millions of lives.

Artemisinin-Based Treatments

Artemisia absinthium Artemisinin is most effective when used with a cocktail of drugs that prevent resistance. Artemisinin sold alone sells for about $5 while cocktail sells for about $6. One combination of drugs with artemisinin and lumefantrine is sold by its manufacturer Novartis to the WHO for $2.40 per dose, which the drug maker says is slightly less than what it costs to make.

Artemether is one of the most effective drugs in the artemisinin group most commonly used in malaria cocktails known as ACTs. Pills made available in 2006, combine large doses of artemisinin with either amodiaquine or mefloroquine into one pill reducing the number of pills take for a course of treatment for three days from 32 pills to six pills and prevent artemisinin from being taken alone. The pills are produced by Sanof-Aventis and Far-Manguinhos, Brazil’s state drug laboratory.

In 2008, Brazil launched a cheap new malaria pill call ASMQ in cooperation with the Geneva-based nonprofit group Drugs for Neglected Diseases (DNDi) and the Indian drug maker Ciola that reaches the goal of providing a malaria remedy that cost less than $2.50 a treatment. ASMQ is not patented and is sold at cost by it suppliers. Recommended by the WHO, it is a combination therapy, or ACT, made of artemisinin-based artesunate and another anti-malaria drug, mefloquine. The two drugs are sold separately but if you buy them separately they cost between $4 and $7. The ASMQ treatment consists of taking one or two tablets a day, depending on the age of the patient, for three days. The two drugs are combined so they can be taken together in their correct proportions. DNDi, working with Sanofi-Aventis SA, launched its first combination treatment for Africa in 2007 but it was unsuited for Latin America and Southeast Asia where there are different resistance problems.

In the United States, the first drug with artemisinin — Coartem made by the Swiss company Novartis — was approved in 2009. Coartem combines artemisinin with lumefntirne, a drug developed by Chinese scientists which does not kill the parasites as quickly as artemisinin but remains in the blood longer, killing lingering parasites and helping prevent the parasites from developing a resistance to artemisinin. Coartmen was introduced in 2001. It has been approved in over 80 countries and is sold by Novartis at cost to the WHO and medical charities for about 80 cents a dose. Novartis had sold over 200 million treatments for use in Africa as of 2009 and claims it has saved more tam 500,000 lives. Novartis supplies Coartem at cost to the WHO. It is supplied mainly by the Holley Corporation, which is growing qingpao in orderly rows on plantations and investing in the development of high yield seeds.

Artemisia Annua Production

quinineDemand for sweet wormwood has outstripped supply and shortages of the plant have caused prices to soar. In 2004 prices rose from $115 per pound to over $400 a pound in a matter of months. Artemisinin is difficult to manufacture in a laboratory and researchers are trying to make it using bioengineering. See Gates Below

Demand for qinghao is very high and the Chinese government is anxious to cash in. A small airport and railroads to the area where it is grown are being built. Production in 2008 was estimated to be around 20,000 tons. The aim os to boost that figure quickly to 30,000 tons or 40,000 tons a year.

Ding Derong, an expert on qingpao at China’s Southwest Agriculture University, told the New York Times, “This is a very easy thing to plant and grow, but it is hard to cultivate good quality seeds. At first, farmers will choose cheap seeds over good ones. The result is there will be a lot of disorder.” A spokeswoman for the Holley Corporation, the largest Chinese producer of artemisinin and the main supplier for Novartis, said the key to improving quality and increasing production was “organizing farmers to start standardized cultivation.”

Even though China is the solo source of sweet wormwood, it sells the plant to Novarsis, who makes and distributes anti-malaria drug at cost, rather than developing drugs itself.

Chloroquine and Mefloquine

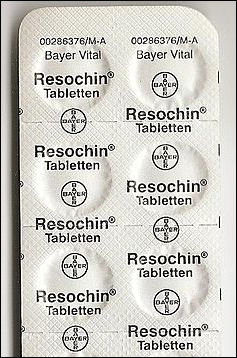

Chloriqune, a synthetic drug similar to quinine, is taken as a malaria treatment and prophylactic. Developed in 1934 in Germany by a researcher working for Bayer, it was not used in World War II, even though an anti-malaria drug was desperately needed in the Mediterranean and Asia-Pacific theaters, because it was thought to be toxic and only the Germans knew about it.

Chloroqine works by disrupting the mechanism that malaria parasites use to make iron — which is toxic to them — found in the hemoglobin they digest. Normally the parasites avoid digesting the iron by making it insoluble, a process that turns the organs of malaria victims a dark, rusty brown. Chloroqine disrupts this step, causing the parasite to poison itself with iron. Parasites that have developed a resistance to chloroquine are able to pump it out of food-vacuoles before it has time to act.

Chloroquine is easy to make and tablets generally cost consumers only a few cents a piece. They are taken once week while in the malaria-infected area and for two weeks before entering the area and for four weeks after leaving. Malaria can have an incubation period of several weeks which is why the drugs are taken four weeks after returning. There have been numerous cases of the people who stopped taking their medication after returning home and came down with malaria. There have been complaints of hair loss by people taking the drug. In many place malaria-carrying mosquitos are resistant to chloroquine.

Chloriquine, came into widespread use after World War II. At first it seemed like a miracle drug. It and DDT were credited with removing the threat of malaria from 500 million people. But the malaria parasites quickly developed resistance to the drug. The fact that many people took chloroquine as a generally remedy for fever resulted in parasites becoming even more resistant

In places where chloroquine-resistant strains of malaria have been confirmed, people usually take mefloquine. Manufactured by Roche and marketed under the name "Lariam,” tablets of this drug cost as much as $10 a piece in the United States and as is the case with chloroquine are taken once a week while in the infected area and for two weeks before entering and for four weeks after leaving.. Mefloquin has one of the worst reputations for side effects. Many people who have taken it complain of dizziness, fatigue, nightmares, depression and hallucinations.

Doxycycline and Malarone

Another drug taken in chloroquine-resistant areas is doxycycline. Tablets of this drug cost 75 cents to one dollar a piece and are taken daily, starting a day before departure to an infected area and for four weeks after returning. Doxycycline increases susceptibility to sunburn and sometimes causes nausea and make women more prone to yeast infections.

In chloroquine-resistant areas in Africa, chloroquine is often taken in combination with proguanil, a drug taken daily that is not available in the United States but is sold under the name of Paludrine in other countries.

drug given to pregnant

in woman Malawi Malarone is a combination of proguaniland a drug called atovaquone. Produced by Glaxo Wellcome it is taken daily before travel for several days after leaving a risk area. It is used as a suppressive but has shown causal activity against falciparum. Currently only two forms of casual drugs — primaquine and malarone — are prescribed in the United States. Primaquine is as a treatment not a preventative. Travelers need only to take this drug during periods of exposure to malaria-carrying mosquitos.

Traditional Malaria Treatment

Malaria is a good example of a disease in which people who need drugs and vaccines the most are least likely to be able to pay for them. Medicines that cost less than $2.50 can treat the deadliest form of the disease. But sometimes even these are too expensive for the poorest poor.

For many poor people new malaria drugs are too expensive. They often turn to cheaper remedies that cost a few cents and relieve some of the symptoms but do little to address the problem of the malaria parasites. Even worse many turn to ineffective traditional remedies that are rooted in superstition and witchcraft.

Traditional methods of treating malaria are often more effective treating the disease. Some of them help the body fight disease. Other helps the body stay strong with the malaria parasite in it.

Traditional Malaria Treatment. See India.

New Malaria Medicines

mefloquin Lariam In an April 2009 Nature article, researchers at the Veteran Affairs Medical Center and Oregon Health and Science University announced that they had designed a new drug that kills the parasite that causes malaria and keep it from becoming resistant to drugs. Tests on mice showed the compound also helped other malaria drugs work better.

A new malaria drug known as OZ227, or simply as Oz, also holds great promise. Developed by the Indian drug company Ranbaxy and the non-profit Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), it is modeled on the molecular structure of artemisinin and kills the parasite in the same way and is expected to be as effective as artemisinin but cheaper to produce in large quantities because it is synthetic.

Giving intermittent preventive treatments along with routine immunizations to infants whether they have the disease or not hold potential as a preventive measure. Studies have shown that similar techniques with pregnant women reduced their chance of contacting the disease by half.

French researchers have developed a promising drug, called G25, that reduced the spread of the disease by blocking the ability of the protozoa to multiple in the red blood cells of monkeys.

Drug-Resistant Malaria and Fake Drugs

Malaria has become more dangerous as pesticide-resistant and drug-resistant strains of mosquitos have evolved. Chloroquine resistant strains are found all over the world. In some places these strains have developed resistance very quickly, In 1986, for example, none of the Peace Corps volunteers in Benin came down with malaria. In 1987, all of them did. Many strains are also resistant to other two anti-malarial drugs such as mefloquine and doxycycline. By some estimates drug-resistant malaria threatens nearly 40 percent of the world's population.

chloroqine

Some particularly nasty drug-resistant forms of malaria are found in Southeast Asia. In the monsoon jungles of northern Thailand and in the forests along the Thai-Cambodia border, malaria has managed to mutate so quickly that every known preventative medicine is either ineffective or partially effective for reasons that are still unknown. A falciparum Phasmidia with a resistance to chloroquine was discovered in Thailand in 1957. By the mid 1990s about 80 percent of the malaria found on the border of Thailand and Cambodia was mefloquine resistant. Nearly all the people in this area, mostly gems miners, farmers and refugees who fled the Khmer Rogue, come down with malaria. Many get very sick and more die of the disease than in other places. Malaria parasites have developed resistance to medications quicker than other disease-causing agents because they contain a protein that deters anti-malaria drugs the same way that cancer cells sometimes repel chemotherapy.

The WHO said in 2010 that a form of malaria resistant to the most powerful drugs available — artemisinin-based combination drugs, known as ACTs — may have emerged along the Thai-Myanmar border and Vietnam. Artemisinin-resistant malaria first broke out along the Thai-Cambodia border. "If we lose the ACTs, we are back to square one. There are no replacement drugs on the immediate horizon," warned Chan. [Source: Stephanie Nebehay, Reuters, December 14, 2010]

More than a third of malaria drugs examined by scientists in Southeast Asia were fake, and a similar proportion analysed in Africa were below standard, doctors warned last week. “These findings are a wake-up call demanding a series of interventions to better define and eliminate both criminal production and poor manufacturing of antimalarial drugs,” Joel Breman of the Fogarty International Center at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) said. [Source: AFP, May 28, 2012]

Trawling through surveys and published literature, the researchers found that in seven Southeast Asian countries, 36 percent of 1437 samples from five categories of drugs were counterfeit. Additionally, 30 percent of the samples failed a test of their pharmaceutical ingredients. In 21 sub-Saharan countries, 20 percent of more than 2500 samples tested in six drug classes turned out to be falsified, and 35 percent were below pharmaceutical norms.

See Separate Article DISEASES IN ASIA: DRUG-RESISTANT MALARIA, RABIES AND DENGUE FEVER factsanddetails.com

Image Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions ; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets; National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various websites books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022