PLANTS IN JAPAN

Archaeologists working at a 2,000-year-old site in Japan found a seed at the bottom of a grain storage bin. Scientists germinated the seed, which grew into magnolia tree similar to the magnolia trees that grow in the area. When the tree bloomed it produced flowers with six to nine petals. Flowers on the magnolia trees in the area contain only five petals.

Reeds, called “yoshi” or “ashi” in Japanese, used to be so ubiquitous along the edges of rivers and lakes that the name of Japan in the most ancient texts that refer to it is “Ashihara no Nakatsukuni” — Central Land of the Reed Plains.”

Perhaps the most famous tree in Japan is the Jomon cedar on Yakushima Island south of Kyushu. It has a 28-meter circumference and may be 7,200 year old, making it possibly the oldest living thing on the planet.

Hachiijo Island is the home of mushrooms that glow in the dark.

Popular Plants in Japan homepage3.nifty.com ; Invasive Plants in Japan invasive.m-fuukei.jp ; Book: Bamboo in Japan shakuhachi.com ; Forests and Rain Forests: Statistical Handbook of Japan Forestry Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp Essay on Japan’s Forests and History aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japan’s Tropical Forest Action Network jca.apc.org/jatan Amazon Rainforest Foundation of Japan rainforestjp.com ; Japan and Borneo’s Rain Forests news.mongabay.com

Links in this Website: ANIMALS AND ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ALIEN ANIMALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BEARS, DEER, SEROW AND WILD BOARS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TANUKIS, FLYING SQUIRRELS, SMALL MAMMALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SNOW MONKEYS (JAPANESE MACAQUES) Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EAGLES, SWANS, CROWS AND BIRDS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRANES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; IBISES AND CORMORANTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SNAKES, FROGS, LIZARDS AND TURTLES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BEETLES, LAND CRABS AND INSECTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PLANTS AND FORESTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GIANT SQUIDS, SHARKS , THE SEA AND JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; WHALES, WHALING AND DOLPHIN HUNTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PETS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EXOTIC PETS, BIRD FIGHTS AND BEETLES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DOGS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DOG BREEDS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Flora in Japan

The flora of Japan is marked by a large variety of species. There are about 4,500 native plant species in Japan (3,950 angiosperms, 40 gymnosperms, 500 ferns). Some 1,600 angiosperms and gymnosperms are indigenous to Japan. The large number of plants reflects the great diversity of climate that characterizes the Japanese archipelago, which stretches some 3,500 kilometers (2,175 miles) from north to south. The most remarkable climatic features are the wide range of temperatures and significant rainfall, both of which make for a rich abundance of flora. The climate also accounts for the fact that almost 70 percent of Japan is covered by forest. Foliage changes color from season to season. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Plants are distributed in the following five zones, all of which lie in the East Asian temperate zone: (1) the subtropical zone, including the Ryukyu and Ogasawara islands groups; (2) the warm-temperature zone of broad-leaved evergreen forests, which covers the greater part of southern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu; characteristic trees are “shii “and “kashi”, both a type of oak; (3) the cooltemperature zone of broad-leaved deciduous forests, which covers central and northern Honshu and the southeastern part of Hokkaido; Japanese beech and other common varieties of trees are found here; (4) the subalpine zone, which includes central and northern Hokkaido; characteristic plants are the Sakhalan fir and Yesso spruce; (5) the alpine zone in the highlands of central Honshu and the central portion of Hokkaido; characteristic plants are alpine plants, such as “komakusa “(“Dicentra peregrina”).

“Matsu “and “sugi”, Japanese pine and cedar, respectively, are common throughout the Japanese archipelago — even in warm southern regions — and are very familiar to the Japanese people. Pines often make splendid scenery. The most notable scenic spot is Amanohashidate, in Kyoto Prefecture, with more than 6,000 pine trees forming lines on the sandbar. Large pine trees, which grow to a maximum height of about 40 meters, also serve as a windbreak in coastal areas. Small pines are used as “bonsai”, garden trees, and materials for houses and furniture. Pines are also considered to be holy trees. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“People in the olden days were awed by nature and saw in plants and trees symbols of divine spirits. At one time, for example, it was common to worship evergreen trees such as pine, cedar, and cypress because they were thought to provide habitation to heaven-sent deities. The still-common practice of decorating the entrance-ways of houses at New Year’s with pine branches — “kadomatsu”, literally “gate pine” — comes from the belief that this was an appropriate way to welcome the gods.

Bamboo in Japan

Bamboo is a giant grass. There are 662 kind of bamboo in Japan, Japan, ranging dwarf varieties to the 100-foot-tall “mosochiku”. Much of bamboo in Japan is moso bamboo which produces shoots that are popular food and grow incredibly fast. The shoots can reach a height of 20 meters in one or two month. The roots can spread six meters a year and produce dense thickets that are difficult for a person to squeeze through. Near Kyoto one bamboo stalk was observed growing almost four feet in 24 hours. At that rate you could have been able to almost see it grow. [Source: Luis Marden, National Geographic, October 1980]

Bamboo shoots are a popular food and are often harvested by people from bamboo groves near their homes. Known as “takenoko” (bamboo babies), they are gathered in the early spring and dug up by hand. Takenoko is added to soups and stews and is sliced and grilled on barbecues. It needs to be boiled before it can be consumed.

People hunting for bamboo babies look for slight mounds of earth at the beginning of spring. The best ones haven’t emerged from the ground yet and it takes some probing of the ground to find them. Increasingly mild winters have moved the season up to February.

Japan’s bamboo groves are growing out of control and presenting problems for local governments that don’t have the funds to maintain and contain them. In the past bamboo shoots were collected for food and bamboo was harvested from for a variety of purposes but these practices are being done less these days as the market for bamboo and bamboo shoots has become flooded with cheap imports. Imports of bamboo rose from 10,000 tons in 1965 to 90,000 tons in 1985 to 220,000 tons in 2008.

Bamboo Crafts and Uses in Japan

bamboo forest path Bamboo is said to have "1,400 practical and decorative uses" in Japan. The traditional wood and paper Japanese house utilizes bamboo in ceilings, moldings, rain spouts and gutters. Baskets, flutes, dolls, chairs and countless other objects are made from bamboo. It is even possible for a man to buy a five foot long bamboo wife which he throws over one leg to keep cool on summer nights. [Source: Luis Marden, National Geographic, October 1980]

"Bamboo is to said to be like a bird's bones, its hollow stalks make it very light," Christal Whelan wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: There is a saying: "in great storms trees break, but the supple bamboo bends." The strength that lies at the heart of such flexibility is what makes bamboo such a great material, and one that keeps turning up in unexpected guises--as a prime construction material in contemporary vernacular architecture or in soft bamboo rayon garments that easily drape. [Source: Christal Whelan, Daily Yomiuri, February 19, 2012]

“Ubiquitous in Japan, bamboo comes in an astounding array of colors: deep lacquer black, silvery-blue, jade-green, yellow, brown, and even striped. It is used in weaving baskets as intricate as knitwear, and as sturdy ribbing for fans and umbrellas. Its upper brush makes excellent fences tied with hemp, and the plant's many root stubs are left on the flared end of the shakuhachi flute for their sheer finesse. Bamboo charcoal purifies water and deodorizes air, and takenoko bamboo shoots cooked as tempura have a flavor as delicate as artichoke hearts. The one-room museum in Rakusai Bamboo Park in Nishikyo Ward, Kyoto, even houses the crumbling remains of a bamboo plumbing system from the eighth century.

“Shintaro Morita is a fifth-generation master bamboo artisan, who makes baskets and vases in Kyoto. His daughter Tsuyako, who works beside him and runs the shop, told Whelan. “In autumn, we cut the bamboo," she says, "and in February and March we make things." Most of what they use is madake, the same bamboo used by Edison to make the first lightbulbs (See Below).

Edison and Bamboo from Kyoto

Christal Whelan wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: On the connection between the American inventor, Thomas Edison (1847-1931) and the bamboo of Kyoto, Christal Whelan wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, According to a description at the museum in Rakusai Bamboo Park in Nishikyo Ward, Kyoto, Edison was trying to find a filament that would burn long enough to be of practical value for his invention--the electric lightbulb. From his New Jersey lab, the great inventor sent scouts to various countries in search of an appropriate material, and ultimately tested the fibers of about 6,000 plants. [Source: Christal Whelan, Daily Yomiuri, February 19, 2012]

“The one that proved to burn the longest happened to grow in the bamboo groves of Yawata, Kyoto Prefecture. The madake bamboo (Phyllostachys bambusoides) burned a record 2,450 hours. That was the beginning of the global electrical revolution. The inventor then founded the Edison Electric Light Co. to manufacture the electric lightbulbs with bamboo filaments from Kyoto. According to Thomas Edison, a biography by Charles E. Pederson, in 1883, Macy's department store in New York became the first U.S. business to use the incandescent lightbulbs.

“Iwashimizu Hachimangu shrine, established in 859, is located on top of Otokoyama, a mountain lush with bamboo groves in which Edison's scout found the bamboo for the filament that would open the age of electricity. Not only is there a monument dedicated to Edison on the shrine grounds, but since 1934 two festivals a year are held in his honor. Edison's birthday on Feb. 11 happens to fall on National Founding Day when Shinto shrines celebrate the "birth" of the country and offer prayers for the prosperity of the nation. At Iwashimizu Hachimangu, the celebration is followed at noon by a gathering of shrine priests, staff and local people to give thanks to Thomas Edison.

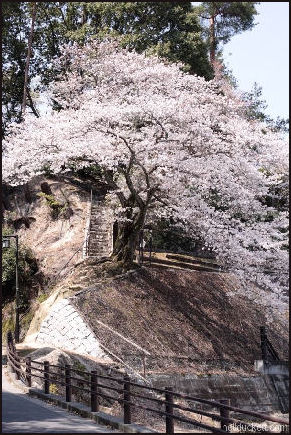

Cherry Trees and Flowers in Japan

The Japanese have a deep love of flowers, They know the names of all sorts of different ones. They favor locally-grown chrysanthemums, carnations and irises. Orchids are popular imports.

If there is a plant that best represents Japan, it is the s” “akura “(cherry tree). The “sakura”, which is native to Japan, has been by far the Japanese people’s favorite from antiquity onward. Modern-day Japanese greet the blossoming of cherry trees in spring as an opportunity to have “hanami “(flower-viewing parties), and many celebrations such as entrance ceremonies to schools and companies are held during this season. Weather forecasts on television and in newspapers broadcast and print charts of the “cherry blossom front” as it moves northwards from Okinawa and ends in Hokkaido. Autumn, when leaves change color, offers another occasion to appreciate nature. Although it is said that people hundreds of years ago would play music and dance beneath the trees, today’s mostly urban Japanese pile into cars and trains in search of autumn’s colors, especially those of the maple tree. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Cherry Trees, See People, Festivals and Holidays

Wisteria and hydrangeas are native to Japan. Hydrangeas are native to the Pacific Ocean side of western and southern Japan. They are associated with the rainy season and early Japan.

Hisaki and sakaki are shrubs that produces a bell-shaped flowers that blooms at night, because it is often fond in old sacred forests around Shinto shrines it is regarded as a sacred flower.

Morning glories have been traditionally been prized for the medicinal values and the laxative effect of the seeds.

Orchids in Japan

On orchids found on the Tokyo area, Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, The first species to bloom was the Cymbidium goeringii or shunran (literally "spring-orchid"), a shy greenish flower with curled lip and slight red markings, that prefers dry oak woodlands. The column is partially hidden by the two side petals, but the standard shape makes this flower an ideal model for studying and sketching basic orchid anatomy. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, May 26, 2011]

“Next came the spectacular kumagaiso or Japanese lady's slipper orchid, a much more outstanding species with wide, fanlike leaves. Like many orchids in this genus, this flower features an enormous inflated lip that looks a bit like a fluffy or feathery slipper. The two side sepals have fused together into a single structure. Kumagaiso are exceptionally rare, but are occasionally encountered in well-tended bamboo groves.

“The ebine calanthe, which blooms a few weeks after the kumagaiso, sports several dozen small flowers on a single stalk. The sepals and side petals are reddish brown, and the birdlike lip is white with a delicate blush of pink that varies among individuals. Sometimes it's hard to tell if the lip is actually pink, or is just reflecting some of the red color from the sepals and sepals.

“The kinran (Cephalanthera falcata), literally "golden orchid," is a colorful species with numerous buttery yellow flowers that stand out sharply in the forest shade; while the ginran (C. erecta), or "silver-orchid," sports tiny, pale, ghostlike white flowers that seem to disappear if you take your eyes off them for a second.

Shunran Orchids

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “One of the first forest-floor perennials to bloom is a local orchard known as the shunran. In Japanese, ran is the generic term for orchid, and shun means simply "spring." This orchid has long, thin leaves, and sends out one to several stalks each topped by a single flower. The flowers are green with some light red markings, and are quite inconspicuous. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, March 15, 2011]

“The shunran looks a lot like the generalized sketch of an orchid flower found in many botany textbooks. The flower consists of an outer whorl of three sepals, which stick out on top and to each side, and an inner whorl of three petals. Two of the petals are of normal leaflike construction, but the bottom petal has evolved into a specialized form, called a lip, that gives orchids their unique appearance.

“The shunran lip is a hard, waxy structure that curls under at the tip. Between the lip and the two upper petals is hidden the column, which contains the flower's male and female reproductive parts. At the very tip of the column are two hunks of pollen, called pollinia. These are usually protected by a hinged cap.

“The shunran flower is designed to be cross-pollinated by insects. The wide stiff lip provides a sort of landing platform for an approaching bee or other potential pollinator. Markings on the lip surface help the insect orient itself and get pointed the right way, which is inside toward the nectar glands. To reach this nectar reward, the insect must force its way between the column and the lip.

“On the way in, the insect's head first pushes up against the tip of the column, but the cap, which is hinged at the top and designed to swing outward and upward, prevents any contact with the pollinia. Next, the insect brushes against the stigma, the receptive tip of the female reproductive organ, located on the bottom surface of the column. If the insect is carrying pollinia from a previously visited flower, the pollen will be transferred the stigma, and the flower will be pollinated. Finally, after receiving a nectar reward, the insect backs out. At this time its head pushes up the cap and picks up the pollinia. Ideally these will then be carried on to pollinate the next flower visited.

“If properly pollinated, the shunran produces a hard, oblong seed capsule filled with hundreds of tiny seeds. The seeds of most plants contain an endosperm (hainyu in Japanese), starchy tissue that surrounds the embryo and provides the initial burst of nutrition for the seed to germinate and grow big enough to produce the first set of leaves. Orchid seeds, however, lack this embryo. To germinate they must come into direct contact with a particular species of fungi that provides them with the carbohydrates and minerals necessary for germination.

Threats to Orchids in Japan

All of these native woodland orchids are highly endangered. Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Because of this peculiar dependency, many species of orchid are extremely sensitive to even minute changes in the environment. They also, however, are susceptible to another grave danger, caused by their very beauty and attractiveness. Japanese people are especially fond of forest-floor wildflowers in general, and orchids in particular. Unfortunately, too many people are not satisfied with simply enjoying the flowers in their natural habitat. They become possessed with what seems like an almost uncontrollable desire to dig them up and take them home. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, March 15, 2011]

“Wild-plucked orchids usually fare very poorly in captivity. Any changes in soil composition will cause them to wilt. Most amateur collectors thus find their plants dying off within a year or two. Also of danger to the orchids are professional collectors who dig up plants to sell on the black market. A potted shunran orchid, for example, sells for 1,000 yen to 1,200 yen in local plant shops.

“In many areas, their traditional countryside habitats, well-tended oak coppices and bamboo groves, have been abandoned, and are now so overrun with tall weeds that there is no longer any space left over for the orchids. The greatest threats to these wild orchids, however, are orchid lovers. Japanese people simply love their beautiful native wildflowers so much they can't resist uprooting a few specimens to take home. These native species are delicate, with very strict soil and light requirements, and in captivity usually wilt away within a year or so. For this reason, we druids tend to keep our orchid discoveries secret!

Almost all the species of forest-floor orchids in my local area are endangered due to overcollecting. Some once-common species have disappeared entirely. In the case of amateurs, the only approach to this problem is through education. To halt commercial collecting, patrolling the countryside is totally impractical. The best solution may be to develop techniques for artificially growing the orchids in large quantities. The price can then be driven down by flooding the market with cheap nursery-grown plants, making commercial collecting unprofitable.

Chrysanthemums in Japan

Chrysanthemums are the national and imperial flower of Japan. Known in Japanese as “kiku”, a word of Chinese origin, they were highly evolved in Japan and China long before they made their way to Europe.

Chrysanthemum mean golden flower. Resembling pom poms and coming in a variety of sizes, they range in color from yellow to chestnut or from pink to crimson and a variety of whites. They blossom in the autumn.

Chrysanthemums have traditionally been an important decorative flower and a popular flower in the flower arranging. Scores of beautiful varieties have been bred over the centuries in Japan. There are bonsai chrysanthemums.

The Japanese Emperor is the occupant of the Chrysanthemum Throne. The Emperor' standard is a gold chrysanthemum on a red field. Only the Imperial family is allowed to use the 16-petal chrysanthemum crest on it tea cups, towels and other items. Sometimes the chrysanthemum symbol with a purple background is seen other places: at Shinto shrines, on the shrine above the ring at sumo tournaments and on nationalist flags.

History of Chrysanthemums

Modern chrysanthemums are a hybrid of two plants: the Korean chrysanthemum — which is native to northern China, north and central Russia and the Carpathian mountains — and a low-growing perennial called C. indium, native to Japan.

There is evidence that the Chinese cultivated chrysanthemums as far back as 500 B.C. They used the flowers and its leaves and roots as a medicines to lower fevers, treat blood heart diseases and reduce inflammations. The Japanese have cultivated them since the Heian period (794-1185). The first chrysanthemums in Japan are believed to have brought bu Buddhist monks from China in the 6th century.

In the city of Himeji, people consider it unlucky to carry chrysanthemums. According to legend a servant girl named O-kiku ("Chrysanthemum Blossom") drowned herself in well after she discovered that one of ten golden plates she was responsible of taking care of was missing. It is aid that every night her ghost rises from the well to count the plates, and when she counts only ten she lets out a terrible scream. Out of respect for her troubled soul the people of Himeji agreed not to grow chrysanthemums in their city. [Source: People's Almanac]

Kudzu

Kudzu is plant native to East Asia that grows like crazy in the American South, where it covers trees like a green canopy. It first arrived in the United States as an ornamental vine shading the Japanese pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition of Philadelphia. Later it became popular with gardeners and was grown as a porch vine in the American South, where it took off as an alien species.

Kudzu is vine that produces a pretty pinkish-purple flower in the late summer around the time kids get ready yo go back to school. A single kudzu plant can produce 60 vines, each of which can grow 20 centimeters a day for up to 15 meters in a single growing season. Their leaves have a large surface areas and the vines are able to reach the sun, fueling the photosynthesis necessary to sustain kudzu’s incredible growth.

Kudzu is a sun-loving plant that grows well in disturbed areas. Known in the American southeast as the “mile-a-minute vine,” it can grow 30 centimeters in a single day and 20 meters in a single season. Although the plant does lose it leaves and dies back somewhat in winter, the vine is really a semi-woody plant, which means much of the above ground part survives. The secret to its phenomenal growth is its leaves which can rotate 90 degrees for maximum expose to sunlight and its strong thick roots which store energy and constantly send out new shoots and runners.

Kudzu are member of the legume (bean) family and is high in protein, nitrogen and fiber. In China, were kudzu is also abundant, the growth is controlled primarily by human beings which use the vines to make rope and the roots to make a hangover medicines. In Japan the leaves have traditionally been used as horse and cattle fodder and the roots were eaten in villages in the winter when rice supplies ran out. The vines were used for making baskets and the fibers can be woven into a rough cloth. The roots are also use to treat upset stomachs and colds.

Kudzu has been called the “vine that ate the South.” A common roadside plant in Japan related to other species found in southeast and east Asia, was initially valued as an ornamental for training on shade trellises after it introduced to the United States. Later, American farmers realized its value as livestock fodder. Animals liked it and being a legume it was rich in protein. In the 1920s kudzu vines were widely planted to control erosion and restore nitrogen to farmland that been overworked. In 1935 it began to be used for erosion control and And animal feed. It covers 1.5 million acres in the United States and grows in some places at a rate over a foot a day. Kudzu is also a problem in South Africa, Australia and some Pacific islands.

Kudzu is found in the United States from Texas to the Atlantic Coast. Covering several million hectares it reduces biodiversity by forcing out native species, prevents forest regeneration and mucks with railroad lines and utility poles. If left unchecked in can quickly cover an open field. Estimates of annual damage run in the hundreds of millions of dollars. In Japan, kudzu is not as much of a pest because there are other sun-loving plants that can outduel kudzu for space. In the old days it was used as fodder for horses and woven into baskets. Traditional medicines from kudzu are said to improve blood circulation and relive muscle aches and fevers.

Other Japanese plants that have invaded the world include: 1) itadori, a plant brought to Europe in the 19th century that has ravaged grasslands and dry river beds in Europe and North America, and is especially troublesome in Britain; 2) wakame, a kind of seaweed that was brought to Europe in the 1970s by oyster shipments and to Australia and New Zealand in the ballast water of large ships and has since spread to South America, Oceania and North America.

Marimo Balls

Marimo is a filamentous species of green lake algae that usually grows on rocks or is free-floating. It grows into its classic "moss ball" shape only under very special conditions, which include a shallow lake bottom where sunlight reaches and gentle water currents that slowly bounce the marimo around. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 21, 2012]

Colonies of spherical marimo are known to have existed at four locations in the lake. In 1897, a colony of ball-shaped marimo was first discovered at Shurikomabetsu Bay in the western area of the lake. More colonies were confirmed later at Churui Bay, Kinetampe Bay and the Osaki area of the lake. The marimo colonies at Shurikomabetsu Bay and Osaki died out by around 1941 due to drastic environmental changes on the lake bottom caused by deforestation in the upper river basin areas, increasing the amount of sediment flowing into the lake. Currently, marimo colonies are only found in Churui and Kinetampe bays.

Lake Akan was once a candidate for a government nomination for World Natural Heritage Site status, but it was not chosen. The spherical marimo in the lake are the oldest in the world and the lake's green algae were spread to Iceland and other countries via the droppings of migratory birds. Currently, marimo colonies are confirmed only in Lake Akan and Lake Myvatn in Iceland, but colonies in the Icelandic lake have been on the verge of extinction as they are heavily covered with sediment.

Efforts to Revive Marimo Colonies

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A project to revive colonies of spherical marimo green algae in Lake Akan in Kushiro, Hokkaido, which are in danger of extinction, is scheduled to start in 2013. The local council for Lake Akan marimo conservation, representing more than 20 organizations including the Kushiro municipal government, plans to set up experimental zones for the revitalization of marimo in an area where the algae, which sometimes resemble green balls of moss, have already become extinct. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 21, 2012]

According to research by the council and other parties, there is an area in Shurikomabetsu Bay where springs exist in an almost straight line about 30 meters long at a depth of 1.5 meters. Researchers plan to observe the process of marimo growth by transplanting some marimo from Churui Bay to multiple experimental areas of several square meters each around the springs and enclosing the areas with barriers.

After observation for three years from fiscal 2013, the council plans to examine whether it will be possible to revive marimo colonies on a greater scale in the future. The revival project is considering enlisting volunteers from among local primary and middle school students and tourists. Naoyuki Matsuoka, chairman of an association for protecting marimo in Lake Akan that is part of the council, said, "We definitely have to protect marimo colonies currently remaining at the two locations in the lake.”

Image Sources: 1) Jun of Goods from Japan 2) 4) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 3) 5) 7) Ray Kinnane 6) Neil Ducket

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013