LOVE OF INSECTS IN JAPAN

The Japanese have traditionally had great affection for insects. Many people have fond childhood memories of reaching for insects with nets and classical Japanese literature is full of stories about crickets, mayflies and fireflies.

“Mushi” is the Japanese word for insect. “Konchishonen” is a word for a boy that loves to play with insects. Astroboy and Pokeman were created by self-professed insect fanatics. Japanese fascination with bugs goes back a long time. A thousand-year-old story “Mushi Mezuru Hime” is about a free-spirted young princess who loves bugs while other girls only love butterflies and flowers and how her passion for insects interest stirs up an interest in boys around her.

Some samurai identified with insects such as praying mantises and dragonflies and placed images of these creatures on their helmets. Some samurai believed that the human soul dwelled in butterflies. Insect motifs can also be found on kimonos, painted screens and lacquerware items. The first reference to the selling of insects dates to 1685 in Kyoto when streets vendors sold crickets in small cages and suspended from sticks. In 1820 fishermen and farmers roamed the countryside in the off season and sold a variety of insects from pushcarts. The first insects shops opened in the late 19th century. In the 1960s, department did a good business selling large beetles to children.

On the film “ Beetle Queen Conquers Tokyo “ (2010), Richard Brody wrote in The New Yorker: “Jessica Oreck’s documentary essay about Japan’s fascination with insects observes the phenomenon with a curious, incisive eye and delves deep into the nation’s culture and history in search of explanations. From urban pet shops specializing in beetles and stores selling paraphernalia for catching bugs and raising them at home, she ranges far afield to record such transfixing wonders as swarms of fireflies glowing on schedule at tourist sites and joins bug hunters on nocturnal ventures to trap exotic species on large, screen-like contraptions. Joining stunning macrophotography by Sean Price Williams to a narration that invokes eighteenth-century aesthetic theory, the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, and the fourth-century development of wet-paddy rice farming, Oreck engages in an enthusiastic cultural anthropology that teases broad horizons from her nuanced attention to the infinitesimal.” [Source: Richard Brody, The New Yorker May 17, 2010]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCARY ARTHROPODS IN JAPAN: GIANT, VENOMOUS HORNETS, CENTIPEDES AND SPIDERS factsanddetails.com

BEETLES AND JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Kids Web Japan on Stage Beetles web-japan.org/kidsweb/archives/cool ; Bug Smuggling thefreelibrary.com Film: ” Beetle Queen Conquers Tokyo “ (2010), a documentary by Jessica Oreck.

Insects Collectors in Japan

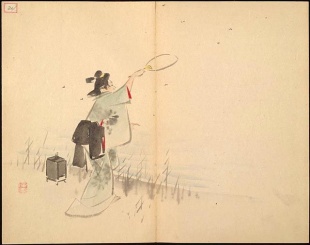

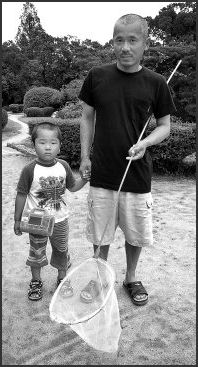

mushi catchers

Japanese are perhaps the world’s most enthusiastic insect catchers. Many children while the hours of their summer vacation in parks and forests chasing after insects with long-handled insect nets and have clear plastic boxes with the insects they catch — mostly beetles, grasshoppers, cicadas, crickets, katydids — at home. Kids often know the scientific names of the insects they catch and identify the body parts and explain what they do. Adult males spends hundred of thousands of dollars on rhinoceros and stag beetles. Neighborhoods sponsor firefly counting outings. Bookstores have entire sections devoted to insects.

An estimated 1 in 10 males is a serious insect or butterfly collector. There monthly magazines and manga comic books devoted to insect collecting. Famous legends and haiku poems explore the joy and wonders of insects and insect collecting. In the old a present of a grasshopper or cricket was a cherished expression of love and friendship.

Pet shops sell a wide variety of containers and accessories to make and outfit an insect homes. Insect collectors that are really into their hobby have professional nets with telescoping aluminum poles, a variety of hand lenses, collecting books and equipment for manipulating and feeding insects. There is monthly magazine devoted to bug collecting called appropriately enough “Gekkan Mushi” ("Bug Monthly"). Pokeman was inspired by insect collecting.

Describing mushi collectors in the 1970s Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “I had never owned, or even seen, a long-handled net before. I was also very surprised to see children keeping insects like crickets and katydids in small wooden cages, feeding them fruit and vegetables and listening to their delicious songs...One small boy was anxious to show me is prize — a huge, beautiful beetle — that “made an incredibly harsh rasping sound every time to boy picked up.” The boy “placed a piece of waste paper in front of the insect’s jaws. He wanted so much for me to see that his beetle could use these scissorlike jaws to make a short but precise cut on the paper.”

Despite their love of insects, Japanese share the near universal disgust of cockroaches. According to the Guinness Book of Records, largest cockroach is 3.81 inches long and 1.77 inches across. It is in the collection of Akira Yokokura of Yamagata, Japan. The cockroach itself is a Megaloblatta longipennis found in Peru, Ecuador and Panama.

Insects in Japan

Shigekatsu Yamaucho wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, that crickets “inform us of the arrival of autumn. Some are daytime singers, while most sing in the evening and through the night. In my childhood, I went out with my friends in the evening to catch them in the nearby fields, to keep them at home. People would breed and raise them to enjoy their nightly recitals at home. Even contests could be held to select champion singers.”

Many of the ladybugs found in Japan are black with red spots. There are orange one with black spots too. The “human face? shield bug has patterns on its back that looks like a kabuki actor with big, busy eyebrows. Japanese beetles were introduced to the United States and became pests.

Darryl Fears wrote in the Washington Post, The so-called kudzu bug, a type of Asian stink bug, has established itself in Georgia. It eats invasive Asian kudzu, a good thing. But the kudzu bug also eats soybeans and other lucrative Georgia legumes. The pest was first spotted in Georgia in 2009. Back then, state entomologists had to search kudzu patches repeatedly for a sign of the insect. But as female bugs lay eggs, with no natural predator, the population exploded in two years, making them easy to sweep into butterfly nets by the thousands. Kudzu bugs are now established in 143 Georgia counties, 42 counties in North Carolina and five in Alabama, according to the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. [Source: Darryl Fears, Washington Post , March 16 2012]

“For a while, they appeared to be a kind of welcome pest. Kudzu bugs, from Japan, chomped on Asian kudzu, reducing growth of the vine by up to 50 percent, said Dan Suiter, an associate professor of entomology at the University of Georgia. But as it turned out, the bug had a taste for other legumes, such as soybeans. It migrates from kudzu in spring to soybean in July, reducing yields by about 20 percent for two years and costing farmers millions of dollars.

“On top of that, the bugs are really annoying. “They’re a general nuisance,” Suiter said. “I was just driving home and had one in my vehicle. They fly very well. We’ve found it on the 40th floor of high rises. When we first found it in 2009, they covered 2,500 square miles in the area. Their known distribution as of last fall is 108,000 square miles.”

Dragonflies (Tombos) in Japan

Dragonflies called tombos in Japan are great loved and associated with summer. There is even a dragonfly museum (in Nakamura, Kocho Prefecture). When they come out — often in vast numbers — its is a clear sign that the rainy season has ended and the hot season has begun. Japanese like dragonflies, it has been said, because of their colors, shape and fighting ability. During the Sengoku period (1467-1568), dragonflies were called “Kachimushi” (victorious insects) and were used as an offerings when warriors prayed for victory in war.

The ancient Yamato court (ca. A.D. 300-700) was so endeared to dragonflies that it named its state “Akitsushima” (Dragonfly Island).According to Dragonfly and Japanese Culture published on weebly.com: Akitsu is an older version of tombo, the Japanese word for dragonfly, and shima stands for island. There are several similar versions of a legend of how this name came to be, all starting with the same central character- a divine emperor said to be the first in Japan by the name of Jimnu. In all versions of this ancient tale this divine ruler sits atop a very high mountain and as he looks down upon the islands of Japan he sees an image that brings to mind the dragonfly or tombo. From here the iterations of the tale diverge: in one version the image of the island in conjunction with the nearby continent looks to him like two dragonflies mating, in another version the islands are like a dragonfly curled on itself to lick its own tail, and in yet another version the islands call to mind the shape of a circle of dragonflies in flight. [Source: dragonflyandjapaneseculture.weebly.com]

Helmets with dragon-fly shaped embellishments were made in Japan in the 17th century. The embellishments were used by high-ranking lords so they could be easily located on the battlefield. Hilts of swords and arrow quivers were also commonly emblazoned with the image of the fearless, swift and courageous dragonfly.In Japan the dragonfly is known as the "victory insect", or kachimushi, because of its hunting prowess and also because it is known to never retreat. Dragonflies are agile and fast fliers and can even hover, but never fly backwards.There is another Japanese legend that further explains the victorious and good fortune beliefs associated with the dragonfly. In this tale the 21st emperor, Yuryaka Tenvo had a horsefly bite him on the arm while out hunting. Before anymore harm could come to him, a dragonfly swooped down and captured the offending bug. This so impressed and pleased the emperor that he renamed the region Akitsu-no (Dragonfly Plain) in honor of his rescuer.

One of Japans staple crops is rice which requires the same water habitat of the dragonfly. Therefore the dragonfly is often associated with the rice paddies of Japan and with that the nostalgia of growing up in a farming community tied to the land.This nostalgia is represented in the inclusion of the dragonfly image in many forms in Japanese art such as the poem/song presented on this site as well as in paintings, and on pottery and fabrics as shown in the photos below. In addition to the nostalgia represented by the dragonfly there is also a folk belief that the tombo is the soul of a departed ancestor come back to visit their loved ones. The summer festival of Obon celebrates this sacred event as depicted in the photo to the left.

Fireflies in Japan

Fireflies (lightning bugs) are also greatly loved. There are not many of them. In places where they can be seen trips are organized to see them.

Firefly viewing is a childhood activity remembered fondly by many older Japanese. Unfortunately urbanization has done a number on firefly populations. In an effort to bring them back special breeding houses have been set up in the Tokyo area. They replicate the firefly stream

ecosystem in a greenhouse. Japan is home to three species of aquatic fireflies. Out of the 2000 or so species of firefly these are the only ones known to be aquatic. This means that for many Japanese the best firefly spotting areas are around streams and rice paddies. One popular children song goes:

“Come over here, fireflies

The water here is sweet and tasty

The water over there is bitter and uninviting”

Jesse Rhodes wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “For nearly a decade, amateur photographer Tsuneaki Hiramatsu spent his summer evenings in the forests outside Niimi, in Japan’s Okayama prefecture. He was intent on capturing the spectacle of firefly mating season, when the males and females vie for attention through blinking codes. As night fell, Hiramatsu began shooting a series of eight-second exposures. He then digitally merged the images, creating connect-the-dot photos of the fireflies’ golden flight paths. The images became a sensation on the Web and were included in a traveling museum exhibit called “Creatures of Light: Nature’s Bioluminescence.” But for Hiramatsu, recognition for his artistry is secondary to engendering appreciation for the natural world. “Fireflies are little seen in areas developed by human beings,” he says. “When I feel the splendor and mystery of nature, I am glad to have everyone share that feeling.” [Source:Jesse Rhodes, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2014]

Cicadas

The loud buzzing, screeching noises made by cicadas (semis) in Japan is a sign that the dog days of summer have begun in earnest. Cicadas are associated with Japanese summers. These massive thumb-sized insects produce a loud buzzing, droning noise in the morning when it is hot. The hotter the weather the more noise they make. Matsuo Basho’s famous poem about cicadas goes:

In the utter silence of the temple,

A cicada’s voice alone

Penetrates the rocks

“Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, Cicadas are large, noisy insects, but are completely harmless. The long strawlike mouth-part looks scary, but is used only to suck sap from trees, and cannot work as a sting. Even small children can easily and safely hold a cicada in their fingers, simply by pressing the wings lightly against the body. Turn the cicada over and check for the flaps to determine the sex (only males have the flaps). Also note the three jewel-like ocelli, or simple eyes (tan-gan in Japanese), arranged in a triangular pattern on the head, between the two huge protruding complex eyes (fuku-gan). These simple eyes do not form clear images but can distinguish between light and shadow and help warn the cicada of the approach of danger from above. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, July 14, 2011]

“Among the most common cicadas in the Kanto region are the abura-zemi (Graptopsaltria nigrofuscata), large (five to six centimeters long) insects with black heads and bodies and mottled brown wings. This species' ocelli are deep ruby red, and their call is a loud, piercing jii-jii, often with a rough tinny finish. The nini-zemi (Platypleura kaempferi) also emerge about this time, but are only about half the size of the abura-zemi.

“In the warmer areas of western Japan the kuma-zemi (Cryptotympana japonensis), slightly larger than the abura-zemi, are very common. These cicadas also have black bodies, but can be easily told apart by their clear wings and softer sha-sha songs. In recent decades, perhaps as a result of global warming, this species has been steadily expanding its range northward and eastward.

Cicadas have been messing up Internet service in Japan by piercing fiber-optic cables to lay their eggs. Normally they lay eggs using their ovipositors to pierce tree branches. They mistake the cables for branches and penetrating them.

Cicada Life Cycle

Cicadas spend many years living int the ground before they emerge for their brief life above it. It is only the male cicadas that make a noise. They do so to attract females. Kumazemi cicadas are the largest cicadas in Japan. They can reach a length of seven centimeters. They are particularly plentiful in the Osaka-Kyoto-Kinki region. These insects live underground for five to seven years, sucking on sap in tree roots with long hollow mouthpieces, and emerge in summer and break free from their last larval shell as adult cicadas. The larval skins can be found around trees. Cicadas spend the hot months of the summer, making noise to attract mates, and mating, and die when the whether gets cold. Just as they signal summers arrival when they appear the signal it’s end when they disappear.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, Cicada nymphs live inside the soil, where they survive by sucking the juice from tree roots. In Japanese cicadas, this underground nymphal stage ranges from two to three years in smaller species to up to seven years in the larger ones. One North American cicada, however, spends 17 years in the soil! [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, July 14, 2011]

“When the cicada nymphs have reached their final larval stage, they burrow upward until reaching a point just below the surface. Separated from the air by only a thin layer of soil, they can feel the temperature and humidity above. As long as the cool weather of the early summer rainy season persists, the cicada nymphs remain in place. After a few consecutive days of hot summer weather, however, they break out and climb up the nearest tree, where they metamorphose into adults. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, July 14, 2011]

Taking their cue from the change in weather, as the rainy season ends and the hottest days of summer take hold, the cicadas emerge from their burrows and are particularly noisy from around sunrise to 10:00am. Only the male cicadas sing, to proclaim territory and attract mates. Inside their abdomen is a hollow chamber fitted with a stiff membrane. By contracting and expanding certain muscles the cicada is able to snap the membrane in and out, much like the thin lid or bottom surface of a tin box. The resultant sound is amplified in the chamber and modulated by two wide valves that work like reeds on a wind instrument, opening and closing to control the escape of air.

“Although cicada larvae live for many years underground, the adults last only a few short weeks. Once their mating is completed they quickly perish. Females use their sharp ovipositors to cut slits into tree twigs, and lay their tiny eggs inside. The eggs quickly hatch and the first-stage larvae drop down to the ground. Those that are not snapped up by ants and other predators immediately burrow in to begin their long subterranean lifestyle.

Japanese Grasshoppers and Locusts

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Using their powerful rear legs as springboards to get airborne, hoppers of all sizes rocket off and fly at a low trajectory for a few meters before dropping suddenly back down again. This is their basic escape strategy. Once on the ground among the weeds their mottled green and brown colors make them nearly invisible. Without a net the best way to catch them is to just keep right on their tail. Jump by jump the insects will tire, and the length of their escape flight will gradually decrease. Eventually you can just reach out and grab yourself a magnificent prize.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, December 16, 2010]

“Some hoppers are truly huge, up to six centimeters long. The big hoppers are not dangerous, but are a bit hard to handle. The back-facing edges of the shin portion of their rear legs are lined with sharp spines, and they can kick out with incredible speed and force. Kicking and raking an enemy with these spines is their desperate last-ditch effort for escape. Also, when held they like to dribble a noxious brown liquid from their mouths, which is almost impossible to wash off later on.”

“One of the most common of Japan's big hoppers is the tonosama-batta, or "king-grasshopper," known as migratory locust in English. The term locust is applied to several different species of grasshopper that show distinctive solitary (tandoku) and gregarious (gunsei) phases. In the solitary phase, all the individual insects go about their own business, interacting only to mate. In the gregarious phase, however, the hoppers form up into enormous swarms that sweep across the landscape, traveling hundreds of kilometers and consuming everything in their path.”

“Entomologists believe that the shift from solitary to gregarious phase is triggered by an increase in population density, often following a period of unusually heavy rains that produces an expanded food supply. When the immature hoppers, or nymphs, are constantly rubbing up against each other, a special hormone is triggered that causes them to metamorphose into the gregarious phase adults.”

“The migratory locust enjoys a wide distribution, from Japan clear across the Eurasian continent to North Africa. In some areas, this species has historically caused great destruction, but nowadays it is the desert locust (Schistocera gregaria) that is most feared. Japan, a land of forested mountainsides and wet valleys, lacks the sort of extensive dry grasslands that favor huge locust swarms. Smaller swarms, however, are occasionally recorded. The gregarious stage of the migratory locust is darker in color, and better equipped for flight, with shorter rear legs but longer wings.”

“Be careful not to confuse the tonosama with the very similar kuruma-batta-modoki (Oedaleus infernalis). Both these species show remarkable individual variation in color and markings, and the most reliable way to tell them apart is to spread out the rear wing (Ouch! Ouch!). The kuruma-batta-modoki's wings have a black crescent-shaped mark, while those of the tonosama-batta are clear with a light yellow tinge.”

Hummingbird Hawk Moth

Describing a hummingbird hawk moth found in Japan, Sam Anderson wrote in the New York Times: “After a few minutes, a strange creature fluttered into my view of the garden. At first it seemed like some kind of bird — a strange hairy hummingbird, maybe, based on the way it was hovering. But then it started to look more like two birds stuck together: it wobbled more than it flew, and it had all kinds of flaps and extra parts hanging off it. I decided, in the end, that it was a big, black butterfly, the strangest butterfly I had ever seen. It floated there, wiggling like an alien fish, just long enough for me to be confused — to try to resolve it, never quite successfully, into some familiar category of thing. [Source: Sam Anderson, New York Times, October 21, 2011]

“The nectar of thistle flowers is hidden deep inside a long, thin tube. Butterflies and moths, with their extendable tubelike proboscises, are ideally adapted to sucking the nectar out of these sorts of flowers. Most incredible among these are the hojaku, or hummingbird hawk moths, that hover in front of the thistles. Their wing beats are so rapid their wings appear only as a blur. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, November 24, 2011]

“Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Numerous species of hummingbird hawk moths are found clear across the Eurasian continent. Japan alone is host of several dozen of them. Closely related forms are distributed in the Americas as well, where they are called simply hummingbird moths. Although most species of moth are nocturnal, the hummingbird hawk moths are active during the daylight hours, especially in the late afternoon. Many of the species show colorful markings, as opposed to the drab grays and whites of nocturnal moths.

“The similarities between hummingbird moths and actual hummingbirds comprise a classic example of what biologists call convergent evolution. In this process, plants or animals in widely separated lineages independently develop structures that function in a similar manner. Both the moths and the birds have evolved similar ability to hover in front of and extract nectar from deep inside long, tubular flowers. The birds suck nectar by probing their long bills and tongues deep into the flowers, while the moths accomplish the same feat employing their proboscises, which can be rolled up or extended much like a garden hose or elephant's trunk. Here in Japan, where there are no native hummingbirds, the moths have a field day.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025