EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS FROM THE GREAT EAST JAPAN TSUNAMI OF MARCH 11, 2011

House Floating at Sea Reporting from Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, Keiichi Nakane wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “I was asking questions of some residents there--I guess it was about 3:30 p.m.--when I heard someone shouting, "Tsunami coming!" I turned back and saw a white line on the water of Kesennuma Bay. Soon the tsunami reached the land, washing away houses and marine product factories. The wave moved toward the community center, located 400 meters from the shore...Suddenly realized how rapidly the water was approaching the building. I rushed up the stairs to the rooftop of the building with the residents. The tsunami hit the center. The building was surrounded by water and wreckage of houses and buildings. The water reached as high as the ceiling of the second floor. It was apparent that the tsunami had hit the apartment building where I'd been staying. I had lost my place to live in. My car was washed away, too.” [Source: Keiichi Nakane, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 16, 2011]

On the experiences of Jessica Besecker, a 24-year-old English teacher in Kesennuma Elizabeth Flock wrote in the Washington Post, “Matsuiwa Junior High School lies close to the coast but high above ground. So minutes later, when the tsunami rose, Besecker could see the giant wave stretched across the horizon, its white crest advancing. The tsunami alarm went off. The announcements were in Japanese, and Besecker couldn’t understand them. As alarms sounded, she thought of the friend she’d promised to pick up. When she asked the principal if she could leave, he told her: “Impossible. The roads have all been washed out.”[Source: Elizabeth Flock, Washington Post, March 29, 2011]

“Besecker saw something catch fire. It was boats out in the harbor, and the boats were carrying the fire into the town on the wave. It looked like a huge wall of fire. Aftershocks began to rock Kesennuma, and it became unsafe to go back into the school building. To Besecker, it felt like standing on a wooden floor, with someone underneath pushing up separate planks all around her.”

Hachinoche

Ayumi Osuga was in her room practicing origami with her three young children — all between the ages of 2 and 6. Osuga ran to meet her husband, packed up her kids in the car, and sped away to a hilltop where her family had a home. "My family, my children. We are lucky to be alive," she said upon returning to her home. "I have come to realize what is important in life." Many of her those around her were not lucky. Next door, rescue workers found the body of her neighbor, dead in the fetal position at the bottom of a stairwell. [Source: Daily Beast, Yahoo News]

Links to Articles in this Website About the 2011 Tsunami and Earthquake: 2011 EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI: DEATH TOLL, GEOLOGY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ACCOUNTS OF THE 2011 EARTHQUAKE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DAMAGE FROM 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TSUNAMI WIPES OUT MINAMISANRIKU Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SURVIVORS OF THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DEAD AND MISSING FROM THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CRISIS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT Factsanddetails.com/Japan

False Sense of Security Before the 2011 Tsunami

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The Omachi area, which is about a kilometer from the coast, was not affected by the 1960 Chilean quake. As a result, local residents believed tsunami would never reach the area. When they held a study session to prepare for powerful earthquakes and tsunami two months before the March 2011 quake, they only discussed accepting survivors from other areas and preparing meals for them. They never imagined they would be tsunami victims themselves. "I remember the time [of the tsunami caused by the Chilean quake], but I never thought a stronger tsunami was possible," Sugano said. "I was much too optimistic." [Source: Hirofumi Morita, Fumito Nagase and Manabu Nakajo, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 17, 2011]

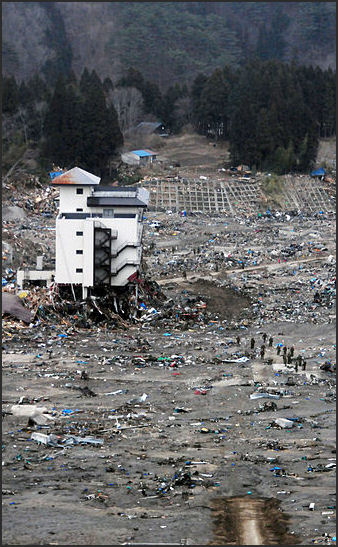

“In the 2011 Tohoku quake, a 10-meter wave of water poured into the Omachi area and instantly smashed shops and houses to matchwood. Although there is some high ground north of the area, very few local residents headed toward it to reach safety. Nearly 60 percent of people belonging to the area's neighborhood association are still missing.” "All of us thought the tsunami would never reach our places. But we were wrong," said a 63-year-old man who lives in an area about one kilometer inland from the Omachi area. His house was destroyed in the tsunami.

“When a major quake hit Chile in February last year, the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry's Tohoku Regional Bureau proudly announced that the embankment helped keep back the tsunami that reached the area,” the Yomiuri Shimbun. "Some people had built new houses near the coast because they were so confident in the embankment," the Kamaishi resident said with a sigh as he stood in front of the debris of destroyed houses.

“In the city's Sanrikucho Okirai area, 19 people were killed in the 1933 Showa Sanriku quake and ensuing tsunami. Shinsaku Katayama, 85, a survivor of that tsunami who works in the construction business and lives in the area, has given lectures at primary and middle schools to increase teachers' and students' awareness of the danger of tsunami, using notes of the 1933 disaster he compiled over a one-year period. Katayama said the number of participants in local disaster drills had fallen over the past few years and he felt awareness of the danger of tsunami had declined.” "Because of the embankments, they never imagined they'd be hit by tsunami. They acted as if nothing untoward would happen," he said with an air of despair.

Local and prefectural governments moved designated shelters to higher ground, compiled detailed evacuation routes and redrew hazard maps. One official told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “We believed we had done everything possible based on very detailed assumptions but...I wondered what else we could do?”

Tsunami Coming

Tsunami Warning System and the 2011 Tsunami

Japan’s “massive public education program” is credited with saving thousands of lives. The coastal towns had an effective early warning system that warned people to get to high ground before the tsunami struck. Most of the residents of the tens of thousands of homes that were swept away survived. Matthew Francis of URS Corporation and a member of the civil engineering society’s tsunami subcommittee, told the New York Times that education may have been the critical factor. “For a trained population, a matter of 5 or 10 minutes is all you may need to get to high ground,” he said. This contrasts to the much less experienced Southeast Asians, many of whom died in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami because they lingered near the coast. According to Japanese media reports many people originally listed as missing in remote areas turned up in schools and community centers, suggesting that tsunami education and evacuation drills were indeed effective. [Source: James Glanz and Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times, March 11, 2011]

Vasily V. Titov, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center for Tsunami Research, told the New York Times the coastal areas closest to the center of the earthquake probably had about 30 minutes before the first wave of the tsunami struck. “In Japan, the public is among the best educated in the world about earthquakes and tsunamis,” he said. “But it’s still not enough time.” Complicating the issue, he added, is that the flat terrain in the area would have made it difficult for people to reach higher, and thus safer, ground.

An old man near a village near Sendai told the BBC: "The faster people ran, the more chance they had of surviving." Mark Magnier wrote in Los Angeles Times: “Chiya Yamane... remembers hearing the tsunami warning; then the desperate attempt to get away."But I'm 84," Yamane said. "And very slow." It was a rescue worker who appeared in time to carry her on his back, up the mountainside to higher ground and safety. "A great, great blessing," she says, though she knows too that being saved meant her ordeal was just beginning.

Reporting from Shintona, Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian: Many of the victims are likely to be elderly people, which could prove one of the defining characteristics of this disaster...Several locals said the young had been able to flee quickly when the tsunami warning was issued, but that older people found it harder to run. “There are many old people here. We have evacuation drills, but people could not get to the meeting place in time. The tsunami was beyond our expectations. We must reflect on our shortcomings," said Jiro Saito, the head of the local disaster countermeasures committee.” [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, March 13 2011]

The mayor of Ishinomaki, where thousands died, told the Washington Post he wondered if the warning system worked too well over the years — if some people had grown complacent. “We are too used to earthquakes and hearing alarms,” he said. A survivor in Arahama, Miyagi Prefecture told the Wall Street Journal the earthquake knocked out the power instantly so many people didn't know a tsunami, which arrived 40 minutes after the earthquake, was coming.

Inadequacy of the Tsunami Warnings

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: In the imagination, tsunamis are a single towering wave, but often they arrive in a crescendo, which is a cruel fact. After the first wave, survivors in Japan ventured down to the water’s edge to survey who could be saved, only to be swept away by the second. In all, twenty thousand people died or disappeared along a stretch of the Japanese coast greater than the distance from New York to Providence.

Tsunami Has Come

The agency issued severe tsunami warnings at 2:49 p.m., three minutes after the quake occurred, in coastal regions in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures.At 3:20 a.m. on March 12, 2011, the agency issued tsunami warnings and alerts to all coastal regions. It was not until 5:58 p.m. on March 13, two days after the quake, when all warnings and alerts were lifted.

Initially, the agency announced predictions that the tsunami would be six meters high in Miyagi Prefecture and three meters high in Iwate and Fukushima prefectures. But the actual heights exceeded 10 meters in many areas and even reached 33 meters in Minami-Sanriku, Miyagi Prefecture. "It was as if the tsunami fell from the heavens," one survivor recalled. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 12, 2012]

The agency noticed how there was a lengthy delay for evacuating after the announcement, which signaled that perhaps the urgency of the situation was miscommunicated. The agency then decided to change the way of communicating predicted wave heights for earthquakes deemed to be magnitude 8 or stronger. In the first warning announcements in the future, the agency will not reveal predicted tsunami heights and instead express the heights vaguely as "huge" and "high" to encourage people to evacuate promptly.

Evacuation Area Not Safe Enough

Describing the experience of a third-year student and her grandfather, Aki Nakamura wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Not long before the tsunami arrived, Kazumi Osawa, 15, and her grandfather Tokichi, 87, left their home in the seaside district of Minami-Hama in the village immediately.” They “went to a vacant lot designated as an evacuation area. The evacuation area was near the sea, but was on a hill and was more than 20 meters above sea level. About 20 people had already gathered there when Osawa and her grandfather arrived.” [Source: Aki Nakamura , Yomiuri Shimbun, April 25, 2011]

“Out at sea, Osawa could see what looked like a line of white smoke. "Is that a tsunami?" she wondered. Osawa reached for her mobile phone to take a photograph, and when she looked back out to sea a moment later, a huge blue wave had begun to build behind the white line. She looked for her grandfather but could not see him. When other people started to scream and run, Osawa rushed farther up the hillside with them, pushing through the branches of the trees. When she looked back, Osawa saw a house next to the evacuation site engulfed in

Eyewitness Account of the Tsunami of 2011 in Shizugawa

Sendai Minami Sato, a 16-year-old resident of Shizugawa, told AP she thought the town's thick, story-high harbor walls would protect against any big wave. Besides, she said her home was perched on a hilltop about two kilometers from the water's edge. It was also just below a designated "tsunami refuge" — an elevated patch of grass that looked safely down across the town's highest four-story buildings. But the colossal wave that slammed into Shizugawa last week "was beyond imagination," the high-school student said. "There was nothing we could do, but run." [Source: Todd Pitman, Associated Press]

Todd Pitman of Associated Press wrote: “When Sato first saw the colossal brown wave rushing toward Shizugawa it looked small enough for the walls arrayed along the harbor — hundreds of yards (meters) of thick concrete slabs — to stop it. But as the tsunami slammed into the harbor edge, it was clear the walls would be useless. Sato — watching from her hilltop home — saw the surging water easily engulf not only the walls, but crash over the top of four-story-high buildings in the distance. Sato grabbed her 79-year-old grandmother and started running up a pathway behind her home to the tsunami refuge. But there, she saw several dozen people who had gathered already on the move. “Run!” screamed one. “The water is coming! It's getting higher!” shouted another.

“The wave fast approaching, Sato ran up the steps into a Shinto shrine, past a cemetery and kept going, finally coming to a halt out of breath beside a cell phone tower. The surging sea swept over the refuge below them, picking up 16 cars that had been parked neatly in a row and cramming them chaotically together into a corner of the parking lot. Below, the ocean had swallowed all of Shizugawa, rising above a four-story mini-mall and the town's hospital, two of the few buildings still standing — but totally gutted — when the wave receded. “I thought I was going to die,” Sato said as she gathered up two sweaters, two books and a pillow from her ruined house, whose missing front wall looked out over the town.

Accounts of the Tsunami by English Teachers in Ishinomaki

Wayaku Steve Corbett, the English teacher in Ishinomaki, told the Washington Post, he turned on the radio and heard a man speaking frantically: “It is now 2:55 p.m. At approximately 3:00 p.m., a tsunami six meters [19 feet] in height will reach land in Miyagi prefecture. Move now to the highest ground you can find.” Corbett gunned his car to the nearest hill. “I thought I was running for my life with the end of the world chasing me,” he said. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Brigid Schulte and Joel Achenbach, Washington Post, March 29, 2011]

The disaster hit Ishinomaki — a farming and fishing community of 160,000 about 50 kilometers northeast of Sendai — hard. Of 8,000 people still missing across northeastern Japan, 2,770 are from Ishinomaki; it also has the highest confirmed death toll, 3,100.

At Mangokuura Elementary School, Taylor Anderson — a 24-year-old English teacher from Richmond — had led their students onto the playground and had helped parents retrieve their children. More than 300 of the kids had been swiftly whisked away when the tsunami warning sounded. About 50 remained. The teachers decided to move them to a nearby junior high that was farther inland. Anderson helped, then jumped on her bike. “A tsunami will come,” a teacher, Fuminao Takada, recalls warning her. “I know,” Anderson replied in Japanese, nodding.

The teachers saw her pedaling away, standing high on the bike, pumping furiously. Anderson headed down Route 398, the Onagawa Highway, which paralleled the coast, not far from the open water of Ishinomaki Bay.

The morning after... the scale of the disaster in Ishinomaki became clear. At Okawa Elementary School, only 31 of 108 students who had shown up for class were known to have survived. The rest were dead or missing. Following the same well-practiced drill that had been performed at Taylor Anderson’s school, the students had gathered on the playground to wait for help — and then were swept away by the tsunami.

In the days afterward, the American teachers sent texts, e-mails or updated their Facebook pages when they could get a wireless signal. They tried to account for all 11 teachers who had been stationed in Ishinomaki. Corbett went from shelter to shelter, and from hospital to hospital, with a list of names. Aaron Jarrad was finally able to send an e-mail to his family: “I love you all dearly im safe please don’t worry too much” The only one missing was Anderson.

The school where she had taught that day had barely been damaged by the waves, and the U.S. Embassy initially told her family that she’d been spotted at a hospital. But when Anderson’s friends pressed embassy officials, they said they had spoken too soon. Eleven days after the earthquake, Anderson’s body was found near a high school along the highway near the ocean, her friends said. She had made it about halfway back to her apartment.

Surfer Rescues Wife from Tsunami in Ishinomaki

Soma Hideaki Akaiwa, 43, said he was at work a few miles away when the tsunami hit, and he rushed back to find his neighborhood inundated with up to 10 feet of water. Mark Magnier wrote Los Angeles Times: “Not willing to wait until the government or any international organization did, or did not, arrive to rescue his wife of two decades — whom he had met while they were surfing in a local bay — Akaiwa got hold of some scuba gear. He then hit the water, wended his way through the debris and underwater hazards and managed to reach his house, from which he dragged his wife to safety. "The water felt very cold, dark and scary," he recalled. "I had to swim about 200 yards to her, which was quite difficult with all the floating wreckage." [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, March 17, 2011]

“With his mother still unaccounted for several days later,” Magnier wrote, “Akaiwa stewed with frustration as he watched the water recede by only a foot or two. He repeatedly searched for her at City Hall and nearby evacuation centers. Finally, on Tuesday, he waded through neck-deep water, searching the neighborhood where she'd last been seen. He found her, he said, on the second floor of a flooded house where she'd been waiting for help for four days.” "She was very much panicked because she was trapped with all this water around," Akaiwa said. "I didn't know where she was. It was such a relief to find her."

Floating in the Sea Off Ishinomaki After the Tsunami

The Washington Post reported: Toshikatsu Kumagai, a 34-year-old newspaper reporter, “thought he knew about tsunamis. He remembered the last one, just a year ago, after the Chilean earthquake sent a wave across the Pacific. By the time it hit Ishinomaki, it was ankle-high and barely slapped the beach. So he wasn’t perturbed by this latest tsunami warning. Driving his white Honda home on a road near the coast, he hoped to see the wave come in.” [Source: Andrew Higgins, Brigid Schulte and Joel Achenbach, Washington Post, March 29, 2011]

Around 3:20 p.m., as he neared a bridge over the Satagawa, a usually placid river on the western side of Ishinomaki, he saw a truck in front of him come to an abrupt stop. He got out of the car, more curious than alarmed, and started taking photographs...Then, the screams...”I heard this strange sound — zah-zah-zah — and saw water splashing over the bridge. I thought “This is a tsunami.” “His car was blocked by the truck. He had to make a run for it. With the water racing toward him, he ran to the side of the road and spotted a fence. He would climb it, he told himself, and stay above the water. That was when the wave swallowed him up.”

Tsunami whirlpool “So this is what dying is like,” Kumagai thought. “Kumagai, had never learned to swim. Now he found himself in what had become, for the moment, an extension of the Pacific Ocean — a great mass of seawater tipped by the earthquake onto the shores of northern Japan. He struggled to stay above the surface, freezing and battered by broken pieces of the world he once inhabited. He found rescue in the form of a plastic tub that bobbed in the water. The tub kept him afloat. He eventually saw the red hull of a capsized boat and, exhausted, clambered atop it.”

“As night fell, the snow came. A house torn from its foundations floated by with people clinging to the roof. They shouted to him, then disappeared into the darkness. His own sanctuary twisted in the water but stayed in place, snagged on debris. “I just sat still trying to not waste any energy,” he recalled. He dozed off briefly. He startled awake to find the nightmare real.”

“Daybreak brought a glimmer of hope: A helicopter buzzed overhead. He waved. No one waved back. The helicopter was surveying a coastline of such overwhelming destruction and tragedy that a man clinging to a capsized boat was easily overlooked. It was not until well into morning, some 18 hours after the tsunami carried him away, that another helicopter spotted Kumagai and hoisted him to safety. Soon he was at the Red Cross Hospital. Though bruised and worried about the numbness in his leg, he suffered most from what he didn’t know. He didn’t know who had lived and who had died. He didn’t know if his mother and father had survived. There were so many people with worse injuries that he was quickly released from the hospital. He finally tracked down his parents, brother and pet cat, Chibi. They were among the lucky ones along this ravaged coast.

Television footage on Friday shot from a helicopter showed a large whirlpool offshore created by the tsunami that tossed around ships. Also in Ishinomaki, 81 people were taken for the ride of their lives Friday when the boat they were on was torn from its moorings, thrown out to sea, and tossed around in a massive whirlpool created by the tsunami. Fortunately, the Japanese navy found the boat at sea and every one of its passengers was airlifted to safety. Watch raw video of ships being tossed in the water here. [Source: Jiji Press, Daily Beast ]

Running from the Tsunami Near the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant

Tsunami at Fukushima Power Plant When earthquake stopped, Michael Alison Chandler wrote in the Washington Post, “Sakiko Araki, a petite, fast-talking 62-year-old woman, sprang into action. Sakiko had been through disaster training and was accustomed to handling crises as the head nurse at a hospital. She had played out multiple disaster scenarios in her mind, talked them over with her less interested husband, and fretted about what to do about the elderly and physically disabled people in the neighborhood. Long ago, she had prepared a bag with survival essentials, including a blanket, thermal insulation, cash, identification. She had set aside certificates of their insurance.” [Source: Michael Alison Chandler, Washington Post March 29, 2011]

“She started loading the car. While she packed, her husband went to change his clothes so he could begin cleaning the house. He didn’t hear the messages from roadside speakers warning that a tsunami was coming and ordering people to evacuate. He only heard his wife screaming to him: “Forget about the house! We have to go.” “My whole mind was preoccupied with fixing the house,” he said. “I didn’t think it was going to be so serious. . . . If not for her, I would have died.”

“Sakiko drove. They followed directions from the speakers sending them to a shelter at a senior center a few miles away. On the way, Sakiko navigated the car around dozens of new cracks in the road. Nobikuki looked back and saw a spray of water rising above the arching pine trees that lined the coast. The couple were spared the sight of their house — and their neighborhood — being engulfed by the waves. Nor did they hear the crunching, creaking sound it made. A neighbor described both in detail to them later that day.”

“When they got to the shelter, they found about 100 people gathered. Nobukiki went around counting heads and trying to account for neighbors who weren’t there. Were they at work? School? Had anyone seen them that day? Sakiko said people at the shelter were shocked but spoke optimistically at first, cheering one another by saying that everything would be okay, that they would start over in a few days.”

Water Pushing Fire and Floating on a Mattress in Kesennuma

NHK television showed images of a huge fire sweeping across Kesennuma, a city of more than 70,000 people in Miyagi Prefecture known best for exporting shark fins to China. Whole blocks appeared to be ablaze. Describing the experience of one family there Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The afternoon of March 11, Tomiko was home in bed, being cared for by Hideo Sasaki, one of her sons-in-law. The bluff above the bay afforded a graphic view of the calamity following the earthquake, something nobody could have imagined happening because the bay was set back far from the open sea. But as the tsunami wave roared inland, the narrowing of the channel only increased its height and ferocity. Among the ships in the bay was a tanker that burst into flames, spewing burning oil as it slammed into shore. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, March 19, 2011]

"I could see the big wave covering the town below me. All the houses were like toys under the great power of nature," Sasaki told the Los Angeles Times. "On the top of the wave, there was fire. You would think that the water would put it out, but instead it rode into shore and then everything caught fire."

“The house on the bluff was just high enough to be spared the fire,” Demick wrote. “But the electricity knocked out by the disaster cut off the respirator. Tomiko's lungs filled up with phlegm and she suffocated. She died at midnight....Meanwhile, her husband, 81, was missing. He had been under treatment for a minor stroke at a nursing home near the waterfront that had been knocked down by the wave.” "The wave was so big. We were sure that Tadashi had died," Sasaki said. After all, 50 others in the nursing home had been killed.”

“The family was mourning him along with his wife, when on Monday, three days after the quake, a neighbor breathlessly ran up to tell Sasaki that his father-in-law had been spotted in one of the shelters set up in the local school. The electricity was out, so nobody had been able to telephone. Against all odds, his mattress has been swept off the bed by the tsunami waves and carried him like a magic carpet to a stairwell that led to the roof. He'd waited there for 48 hours before he was rescued and, despite the cold, was in good enough shape to go directly to the shelter rather than the hospital.”

Floating Debris Near Sendai

Surviving in a Wheelchair in Kesennumma

On the first floor of Riverside Shunpo nursing home for the elderly in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, Norie Kanno, 86, was singing karaoke at an event at the facility when the tsunami hit the building ,” the Yomiuri Shimbun reported.” Kanno, who was wheelchair-bound, and the others evacuated to the kitchen. In less than five minutes, the kitchen was filled with water, which rose higher than Kanno's head. "I thought I should focus on not swallowing water," said Kanno, who covered her mouth with a scarf and closed her eyes in the water.

Kanno nearly fell unconscious from a lack of oxygen. A few minutes later, another big wave hit the kitchen, making her body float. The next thing she knew, she and her wheelchair sat on the one-meter-tall table, on which she used to dine with her housemates. "I survived. It's a miracle," Kanno said. With the help of nursing home staff, she evacuated to the building's rooftop. Waiting for rescue, Kanno saw houses being pushed out to sea, driving her to tears. About 50 people died at the nursing home. Like Kanno, two other elderly people in wheelchairs survived by floating onto the table merely by chance. "I'd like to live a healthy life for my friends," Kanno said.

Image Sources: 1) Mostly U.S. Navy; 2) Video Grabs from NHK and Asahi Television

Text Sources: New York Times, Yomiuri Shimbun, Daily Yomiuri, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Kyodo News, National Geographic, The Guardian. Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012