DEAD AND MISSING FROM THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI OF MARCH 11, 2011

Soma Before The total number of casualties confirmed by Japanese National Police Agency in March 2019 was 18,297 dead, 2,533 missing and 6,157 injured. As of June 2011 the death toll reached 15,413, with about 2,000, or 13 percent , of the bodies unidentified. Around 7,700 people were missing. As of May 1, 2011: 14,662 were confirmed dead, 11,019 were missing, and 5,278 were injured. As of April 11, 2011 the official death toll stood at than 13,013 with 4,684 injured and 14,608 people listed as missing. The death toll as of March 2012 was 15,854 in 12 prefectures, including Tokyo and Hokkaido. At that time a total of 3,155 were missing in Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Fukushima, Ibaraki and Chiba prefectures. The identities of 15,308 bodies found since the disaster, or 97 percent, had been confirmed at that time. Accurate death figures were hard to determine early on because there was some overlap between the missing and dead and not all residents or people in areas devastated by the tsunami could not be accounted for.

A total of 1,046 people aged 19 or younger died or went missing in the three prefectures hit hardest by March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in 2011 according to the National Police Agency. A total of 1,600 children lost one or both parents. A total of 466 of the dead were 9 or younger, and 419 were aged 10 to 19. Of the 161 people aged 19 or younger reported as missing to police headquarters in the three prefectures are included, the number of dead or missing people in these age brackets totals 1,046, according to the NPA. By prefecture, Miyagi had 702 deaths among people under 20, followed by 227 in Iwate and 117 in Fukushima. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 8, 2012]

About 64 percent of victims were aged 60 or older. People in their 70s accounted for the largest proportion with 3,747, or 24 percent of the total, followed by 3,375 people aged 80 or older, or 22 percent, and 2,942 in their 60s, or 19 percent. The conclusion that one draws from this data is that relatively young people were better able to make a dash to safety while the elderly, because they were slower, had difficulty reaching high ground in time.

A large number of victims were from Miyagi Prefecture. Ishinomaki was one of the worst-hit cities. When the death toll topped 10,000 on March 25: 6,097 of the dead were in Miyagi Prefecture, where Sendai is located; 3,056 were in Iwate Prefecture and 855 were in Fukushima Prefecture and 20 and 17 were in Ibaraki and Chiba Prefectures respectively. At that point 2,853 victims had been identified. Of these 23.2 percent were 80 or older; 22.9 percent were in their 70s; 19 percent were in their 60s; 11.6 percent were in their 50s; 6.9 percent were in their 40s; 6 percent were in their 30s; 3.2 percent were in the 20s; 3.2 percent were in their 10s; and 4.1 percent were in 0 to 9.

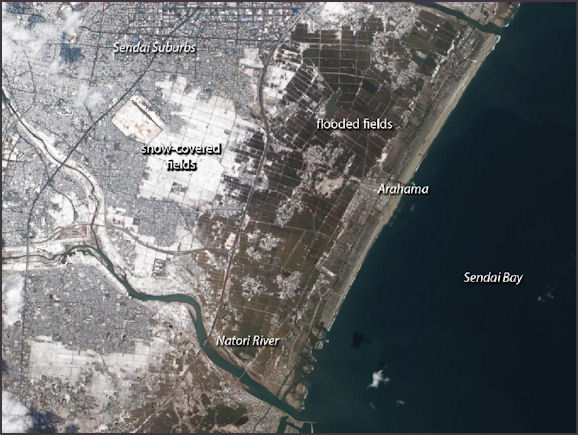

News reports that day after the earthquake said that more than 80 people were killed. Two days late the death toll was in the hundreds, but Japanese news media quoted government officials as saying that it would almost certainly rise to more than 1,000. About 200 to 300 bodies were found along the waterline in Sendai, a port city in northeastern Japan and the closest major city to the epicenter. Later more washed up bodies were found. Police teams, for example, found about 700 bodies that had washed ashore on a scenic peninsula in Miyagi Prefecture, close to the epicenter of the quake. The bodies washed out as the tsunami retreated. Now they are washing back in. Japan’s Foreign Ministry had asked foreign media outlets not to show images of the bodies of disaster victims out of respect for their families. By the third day the magnitude of the disaster was starting to be understood. Entire villages in parts of Japan’s northern Pacific coast vanished under a wall of water. Police officials estimated that 10,000 people may have been swept away in one town alone, Minamisanriku.

Reporting from the coastal town of Natori, Martin Fackler and Mark McDonald wrote in the New York Times, “What the sea so violently ripped away, it has now begun to return. Hundreds of bodies are washing up along some shores in northeastern Japan, making clearer the extraordinary toll of the earthquake and tsunami...and adding to the burdens of relief workers as they ferry aid and search for survivors...Various reports from police officials and news agencies said that as many as 2,000 bodies had now washed ashore along the coastline, overwhelming the capacity of local officials.[Source: Martin Fackler and Mark McDonald, New York Times, March 15, 2011]

Links to Articles in this Website About the 2011 Tsunami and Earthquake: 2011 EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI: DEATH TOLL, GEOLOGY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ACCOUNTS OF THE 2011 EARTHQUAKE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DAMAGE FROM 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TSUNAMI WIPES OUT MINAMISANRIKU Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SURVIVORS OF THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DEAD AND MISSING FROM THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CRISIS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Causes of Death from the Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011

The NPA said 15,786 people were confirmed to have died in the disaster as of the end of February. Of them, 14,308, or 91 percent, drowned, 145 were killed by fire and 667 died from other causes, such as being crushed or freezing to death, according to the NPA. In contrast, in the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake about 80 percent of victims died of suffocation or were crushed under collapsed houses. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 8, 2012]

Several others died due to debilitation or starvation in buildings in or near the no-entry zone set up around the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant after the disaster knocked out the plant's cooling systems and triggered meltdowns. The agency has not included these deaths in the figures because it was unknown if they resulted from the disaster--some of the victims had food nearby, while others decided to remain in their homes in the vicinity of the crippled plant despite being ordered to evacuate.

A forensic examination of 126 victims recovered in the first week after the disaster in Rikuzentakata by Hirotaro Iwase, a professor of forensic medicine at Chiba University, concluded that 90 percent of the town’s fatalities were caused by drowning. Ninety percent of the bodies had bone fractures but those are believed to have occurred primarily after death. The autopsies showed that the victims had been subject to impacts — presumably with cars, lumber and houses — equivalent to a collision with a motor vehicle traveling at 30 to kph. Most of the 126 victims were elderly. Fifty or so had seven or eight layers of clothing on. Many had backpacks with items like family albums, hanko personal seals, health insurance cards, chocolate and other emergency food and the like. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun]

According to the National Police Agency 65 percent of the victims identified so far were aged 60 or older, indicating many elderly people failed to escape the tsunami. The NPA suspects many elderly people failed to escape because they were at home alone when the disaster occurred on a weekday afternoon, while people in other age brackets were at work or school and managed to evacuate in groups.” [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, April 21, 2011]

“According to the NPA, examinations had been completed through April 11 on 7,036 women and 5,971 men, as well as 128 bodies whose damaged condition made it difficult to determine their gender. In Miyagi Prefecture, where 8,068 deaths were confirmed, drowning accounted for 95.7 percent of fatalities, while the figure was 87.3 percent in Iwate Prefecture and 87 percent in Fukushima Prefecture.”

“Many of the 578 people who were crushed to death or died from heavy injuries such as multiple bone fractures were trapped in rubble from houses that collapsed in the tsunami or were struck by debris while they were swept away by the water. Fires, many of which were reported in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, were listed as the cause of 148 deaths. Also, some people died of hypothermia while awaiting rescue in water, the NPA said.”

Chiba University Prof. Hirotaro Iwase, a forensic medicine expert who conducted examinations on disaster victims in Rikuzen-Takata, Iwate Prefecture, told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "This disaster is characterized by an unforeseeable tsunami that killed so many people. A tsunami travels at dozens of kilometers per hour even after it has moved onto land. Once you're caught in a tsunami, it's difficult to survive even for good swimmers."

Near Aneyoshi a mother and her three small children who were swept away in their car. The mother, Mihoko Aneishi, 36, had rushed to take her children out of school right after the earthquake. Then she made the fatal mistake of driving back through low-lying areas just as the tsunami hit.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: In the imagination, tsunamis are a single towering wave, but often they arrive in a crescendo, which is a cruel fact. After the first wave, survivors in Japan ventured down to the water’s edge to survey who could be saved, only to be swept away by the second.

Failure of Japan’s Tsunami Warning System

Takashi Ito wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Although tsunami warnings were issued ahead of the giant wave generated by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, more than 20,000 people on the coast of the Tohoku and Kanto regions were killed by or went missing in the water. It would be hard to claim, then, that the tsunami warning system was successful. [Source: Takashi Ito, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 30, 2011]

When the Great East Japan Earthquake struck, the system at first registered its scale as magnitude 7.9 and a tsunami warning was issued, predicting heights of six meters for Miyagi Prefecture and three meters for Iwate and Fukushima prefectures. The agency issued several revisions of the initial warning, increasing its height prediction over a series of updates to "more than 10 meters." However, the revised warnings could not be communicated to many residents because of power outages caused by the earthquake.

Many residents after hearing the initial warning apparently thought, "The tsunami will be three meters high, so it won't come over the protective wave barriers." The error in the initial warning likely was responsible for some residents deciding not to evacuate immediately. The agency itself admits this possibility.

On March 11, the size of the tsunami was underestimated in the first warning because the agency erroneously figured the scale of the earthquake was magnitude 7.9. This figure was later revised to magnitude 9.0.The major reason for the mistake is the agency's use of the Japan Meteorological Agency magnitude scale, or Mj.

Evacuation Center Deaths

Many people died after taking shelter in buildings designated as evacuation centers. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported the municipal government of Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture, for example, is surveying how residents were evacuated on March 11 after some people pointed out the city government had failed to clearly tell them which facilities they should have taken shelter in before the disaster. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 13, 2011]

Many officials of the Minami-Sanrikucho town government in Miyagi Prefecture died or went missing at a government building when it was hit by the March 11 tsunami. Bereaved families have asked why the building had not been relocated to higher ground before the disaster.

In Kamaishi, the building in question was a disaster prevention center in the city's Unosumai district. Many members of the community took shelter in the facility--which is located close to the ocean--soon after learning a tsunami warning had been issued. The tsunami hit the center, resulting in the deaths of 68 people.

The municipal government interviewed some of the survivors at the center, which revealed about 100 people had evacuated to the building before the tsunami hit. The city's disaster prevention plan designated the Unosumai facility as a "major" evacuation center for medium- and long-term stay after tsunami. On the other hand, some buildings on higher ground and a little away from the center of the community--such as shrines or temples--were designated "temporary" evacuation centers where residents should gather immediately after an earthquake.

The city government examined possible reasons why many people evacuated to the Unosumai facility close to the coast. When it held a briefing session for residents in August, Mayor Takenori Noda apologized for not fully informing them of different types of evacuation centers. The Unosumai district conducted an evacuation drill on March 3, and the center was set as a meeting place. When other communities held similar drills, they usually used facilities nearby--rather than elevated sites--as meeting places for the sake of the elderly, according to residents.

Shigemitsu Sasaki, 62, a volunteer firefighter in the Unosumai district, ran to the disaster prevention center along with his daughter, Kotomi Kikuchi, 34, and her 6-year-old son, Suzuto. The two were visiting Sasaki's house when the quake struck on March 11 and died at the facility. "I've been working as a volunteer firefighter for about 35 years," Sasaki said. "However, I've never heard there're 'first-stage' or 'second-stage' types of evacuation centers."

In Minami-Sanrikucho, 33 officials died or went missing at the town government's three-story, steel-reinforced building for disaster prevention when it was engulfed by the tsunami. The building was next to the town hall. Minami-Sanrikucho was formed in 2005 by merging what used to be Shizugawacho and Utatsucho, the latter of which completed the disaster prevention building in 1996. Because there were concerns over the ability of the building--which was just 1.7 meters above sea level--to withstand a tsunami, a letter of agreement compiled at the time of the merger stipulated the newly formed government should examine moving the facility to higher ground. Takeshi Oikawa, 58, whose son, Makoto, 33, was among the 33 victims, and other bereaved families sent a letter to the town government in late August, saying, "Had the building been moved to an elevated site, as promised in the agreement, they would not have died."

Dead and Missing in Rikuzentakata and Shizugawa

Soma After Todd Pitman of Associated Press wrote: “Immediately after the quake, Katsutaro Hamada, 79, fled to safety with his wife. But then he went back home to retrieve a photo album of his granddaughter, 14-year-old Saori, and grandson, 10-year-old Hikaru. Just then the tsunami came and swept away his home. Rescuers found Hamada's body, crushed by the first floor bathroom walls. He was holding the album to his chest, Kyodo news agency reported. "He really loved the grandchildren. But it is stupid," said his son, Hironobu Hamada. "He loved the grandchildren so dearly. He has no pictures of me!" [Source: Todd Pitman, Associated Press]

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “The official statistics issued here on Monday afternoon stated that the tsunami had killed 775 people in Rikuzentakata and left 1,700 missing. In truth, a trip through the waist-high rubble, a field of broken concrete, smashed wood and mangled autos a mile long and perhaps a half-mile wide, leaves little doubt that ''missing'' is a euphemism.” [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, March 22, 2011

“On the afternoon of Friday, March 11, the Takata High School swim team walked a half-mile to practice at the city's nearly new natatorium, overlooking the broad sand beach of Hirota Bay. That was the last anyone saw of them. But that is not unusual: in this town of 23,000, more than one in 10 people is either dead or has not been seen since that afternoon, now 10 days ago, when a tsunami flattened three-quarters of the city in minutes.”

Twenty-nine of Takata High's 540 students are still missing. So is Takata's swimming coach, 29-year-old Motoko Mori. So is Monty Dickson, a 26-year-old American from Anchorage who taught English to elementary and junior-high students. The swim team was good, if not great. Until this month, it had 20 swimmers; seniors' graduation cut its ranks to 10. Ms. Mori, the coach, taught social studies and advised the student council; her first wedding anniversary is March 28. ''Everybody liked her. She was a lot of fun,'' said Chihiru Nakao, a 16-year-old 10th grader who was in her social studies class. ''And because she was young, more or less our age, it was easy to communicate with her.''

Two Fridays ago, students scattered for sports practice. The 10 or so swimmers — one may have skipped practice — trekked to the B & G swimming center, a city pool with a sign reading, ''If your heart is with the water, it is the medicine for peace and health and long life.'' Ms. Mori appears to have been at Takata High when the earthquake struck. When a tsunami warning sounded 10 minutes later, Mr. Omodera said, the 257 students still there were ushered up the hill behind the building. Ms. Mori did not go. “I heard she was in the school, but went to the B & G to get the swim team,” said Yuta Kikuchi, a 15-year-old 10th grader, echoing other students' accounts.”

“Neither she nor the team returned. Mr. Omodera said it was rumored, but never proven, that she took the swimmers to a nearby city gymnasium where it has been reported that about 70 people tried to ride out the wave.”

Describing the scene at the place where bodies were identified Wines wrote: “In the Takata Junior High School, the city's largest evacuation center, where a white hatchback entered the school yard with the remains of Hiroki Sugawara, a 10th grader from the neighboring town of Ofunato. It was not immediately clear why he had been in Rikuzentakata.'This is the one last time,' the boy's father cried as other parents, weeping, pushed terrified teenagers toward the body, laid on a blanket inside the car. 'Please say goodbye!'

Elementary School Children Killed the Tsunami

Among the dead and missing are about 1,800 students from kindergarten to college. Seventy four of the 108 students enrolled at Okawa Primary School in Ishinomaki were killed or have been missing since the quake-triggered tsunami hit. According to the Yomiuri Shimbun , “The children were evacuating as a group to higher ground when they were engulfed by a wave that roared up the Kitakamigawa river.” The school is located on the banks of the river — the largest river in the Tohoku region — about four kilometers from where the river flows into Oppa Bay. According to the Ishinomaki municipal board of education, 9 of the 11 teachers who were at the school on the day died, and one is missing.” [Source: Sakae Sasaki, Hirofumi Hajiri and Asako Ishizaka , Yomiuri Shimbun, April 13 2011]

“Shortly after the earthquake hit at 2:46 p.m., the students left the school building, led by their teachers,” according to a Yomiuri Shimbun article. “The principal was not at the school at the time. Some of the children were wearing helmets and classroom slippers. A number of parents had arrived at the school to collect their kids, and some of the children clung to their mothers, crying and wanting to rush home, according to witnesses.”

“At 2:49 p.m., a tsunami warning was issued. The disaster-prevention manual issued by the municipal government simply says to go to higher ground in case of tsunami — choosing an actual place is left up to each individual school. Teachers discussed what action to take. Broken glass was scattered through the school building, and there was concern the building might collapse during aftershocks. The mountain to the rear of the school was too steep for the children to climb. The teachers decided to lead the students to the Shin-Kitakami Ohashi bridge, which was about 200 meters west of the school and higher than the nearby river banks.”

“A 70-year-old man who was near the school saw students leaving the school grounds, walking in a line. "Teachers and frightened-looking students were passing by right in front of me," he said. At that moment, an awful roar erupted. A huge torrent of water had flooded the river and broken its banks, and was now rushing toward the school. The man began to run toward the mountain behind the school — the opposite direction from where the students were heading. According to the man and other residents, the water swept up the line of children, from front to back. Some teachers and students at the rear of the line turned and ran toward the mountain. Some of them escaped the tsunami, but dozens could not.”

“Disaster-scenario projections had estimated that, if a tsunami were to occur as a result of an earthquake caused by movement along the two faults off Miyagi Prefecture, water at the river mouth would rise by five meters to 10 meters, and would reach a height of less than one meter near the primary school. However, the March 11 tsunami rose above the two-story school building's roof, and about 10 meters up the mountain to the rear. At the base of the bridge, which the students and teachers had been trying to reach, tsunami knocked power poles and street lights to the ground. "No one thought tsunami would even reach this area," residents near the school said.

According to the local branch office of the municipal government, only one radio evacuation warning was issued. The branch office said 189 people — about one-quarter of all residents in the Kamaya district — were killed or are missing. Some were engulfed by tsunami after going outdoors to observe the drama; others were killed inside their homes. In all of Miyagi Prefecture, 135 primary school students were killed in the March 11 disasters, according to the prefectural board of education. More than 40 percent of those children were students at Okawa Primary School.

John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, “Authorities in this coastal town attribute the deaths to a turn of events no one had anticipated. With its first violent jolt, the magnitude 9 earthquake killed 10 teachers at Okawa Elementary School, plunging the students into chaos. Survivors say the children were urged by three remaining instructors to follow a long-practiced drill: Don't panic, just walk single file to the safety zone of the school's outdoor playground, an area free of falling objects. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2011]

For nearly 45 minutes, the students stood outside and waited for help. Then, without warning, the monstrous wave swept in, demolishing what was left of the school and carrying most of the students to their deaths. Twenty-four survived. "Those children did everything that was asked of them, that's what's so tragic," said Haruo Suzuki, a former teacher here. "For years, we drilled earthquake safety. They knew an event like this wasn't child's play. But no one ever expected a killer tsunami."

There was anger mixed with the grief. Some parents refused to attribute the deaths to a cruel twist of fate. "The teacher should have gotten those children to a higher place," said Yukiyo Takeyama, who lost two daughters, aged 9 and 11. Speaking as though in a trance, she explained that she initially wasn't worried the day the earthquake struck because her daughters had always talked of the disaster drill they knew by heart. But hours afterward, there was still no word from the school.

At dawn the following day, her husband, Takeshi, drove out toward the school until the road buckled and disappeared underwater. He walked the rest of the way, reaching the clearing near the river where he had delivered his children countless times. "He said he just looked at that school and he knew they were dead," Takeyama said. "He said no one could have survived such a thing." She paused and sobbed. "It's tragic."

Report on the Children Lost at Okawa Primary School in Ishinomaki

According to interviews of 28 people — including a senior male teacher and four students who survived being engulfed by the tsunami — conducted from March 25 to May 26 by the local board of education there was considerable confusion about where to evacuate in the minutes before the tsunami pounded the area. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 24, 2011]

According to the report, after the earthquake occurred at 2:46 p.m. students and teachers assembled in the school playground for about 40 minutes before evacuating along a route toward the Kitakamigawa river. They walked in lines, with sixth-grade students at the front followed by younger students.

As they walked to an area of higher ground called "sankaku chitai" at the foot of Shin-Kitakami Ohashi bridge that traverses the river, the tsunami suddenly surged toward them. "When I saw the tsunami approaching, I immediately turned around and ran in the opposite direction toward the hills [behind the school]," a fifth-grade boy said during an interview. Another fifth-grade boy said: "The younger students [at the back of the line] looked puzzled, and they didn't understand why the older students were running back past them." As the water swamped the area, many students drowned or were swept away.

As the tsunami waters rose around him, one boy desperately stayed afloat by clinging to his evacuation helmet. A refrigerator with no door floated past so he climbed inside, and survived by staying in his "lifeboat" until the danger eventually passed.

After he clambered into the refrigerator, the water pushed him toward the hill behind the school, where he saw a classmate who had become stuck in the ground as he tried to flee. "I grabbed a branch with my right hand to support myself, and then used my left hand, which hurt because I had a broken bone, to scoop some of the dirt off my friend," he said. His classmate managed to dig himself out.

The board also spoke to 20 students who were picked up by relatives by car after the quake. A fourth-grade student said when the car they were in was driving past sankaku chitai, a city employee there told them to flee to higher ground.

Some interviewees said teachers and locals were split over where the best evacuation site was."The vice principal said we'd better run up the hills," one recalled. Another said locals who had evacuated to the school "said the tsunami would never come this far, so they wanted to go to sankaku chitai."

One interviewee said the discussion on where to evacuate developed into a heated argument. The male teacher told the board that the school and residents eventually decided to evacuate to sankaku chitai because it was on higher ground.

Woman Watches Her Parents Get Washed Away by the Tsunami

Reporting from Shintona, a coastal town close to the epicenter of the earthquake, Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian: “Harumi Watanabe's last words to her parents were a desperate plea to "stay together" as a tsunami crashed through the windows and engulfed their family home with water, mud and wreckage. She had rushed to help them as soon as the earthquake struck about 30 minutes earlier. “I closed my shop and drove home as quickly as I could,” said Watanabe. “But there wasn't time to save them.” They were old and too weak to walk so I couldn't get them in the car in time.” [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, March 13 2011]

They were still in the living room when the surge hit. Though she gripped their hands, it was too strong. Her elderly mother and father were ripped from her grasp, screaming "I can't breathe" before they were dragged down. Watanabe was then left fighting for her own life. "I stood on the furniture, but the water came up to my neck. There was only a narrow band of air below the ceiling. I thought I would die."

In the same town Kiyoko Kawanami was taking a group of elderly people to the emergency shelter in Nobiru primary school. "On the way back I was stuck in traffic. There was an alarm. People screamed at me to get out of the car and run uphill. It saved me. My feet got wet but nothing else."

Sendai

Man Sacrifices His Life to Set Up Satellite Phone for Hospital in Rikunzentakata

Yusuke Amano wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Sixty-year-old Shigeru “Yokosawa was scheduled to retire at the end of the month, but he died in the tsunami that consumed Takata Hospital in Rikuzen-Takata. Just after the main tremor hit, more than 100 people--hospital staff, patients and local residents who had come seeking shelter--were in the four-story concrete building. Minutes later, people started shouting a huge tsunami was approaching.” [Source: Yusuke Amano, Yomiuri Shimbun Staff, March 24, 2011]

“According to Kaname Tomioka, a 49-year-old hospital administrator, he was on the building's third floor when he looked out the window and saw a tsunami more than 10 meters high coming straight at him. Tomioka ran down to the first floor staff room and saw Yokosawa trying to unhook the satellite phone by the window. Satellite phones are vitally important during disasters, when land lines are often cut and cell phone towers are down.”

“Tomioka shouted to Yokosawa, "A tsunami's coming. You have to escape immediately!" But Yokosawa said, "No! We need this no matter what." Yokosawa got the phone free and handed it to Tomioka, who ran up to the roof. Seconds later, the tsunami struck--engulfing the building up to the fourth floor--and Yokosawa went missing. Hospital staff could not get the satellite phone to work on March 11, but when they tried again after being rescued from their rooftop refuge by a helicopter on March 13, they were able to make a connection. With the phone, the surviving staff was able to ask other hospitals and suppliers to send medication and other supplies.”

Later “Yokosawa's wife Sumiko, 60, and his son Junji, 32, found his body in a morgue...Sumiko said when she saw her husband's body, she told him in her mind, "Darling, you worked hard," and carefully cleaned some sand from his face. She said she had believed he was alive but had been too busy at the hospital to contact his family.”

Missing Workers in Minami-Sanrikucho Saved Lives with Their Last Words

Yoshio Ide and Keiko Hamana wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “As the March 11 tsunami approached, two town employees in Minami-Sanrikucho...stuck to their posts, urging residents to take shelter from the oncoming wave over the public announcement system. When the waters receded, Takeshi Miura and Miki Endo were nowhere to be found. The two are still missing despite a tireless search by their families.” [Source: Yoshio Ide and Keiko Hamana, Yomiuri Shimbun, April 20, 2011]

"A 10-meter tsunami is expected. Please evacuate to higher ground," Miura, 52, said over the loudspeakers on the day. An assistant director of the municipal government's risk management section, he spoke from the office's second-floor booth with Endo at his side. About 30 minutes later, the huge wave hit land. "Takeshi-san, that's it. Let's get out and get to the roof," one of Miura's colleagues recalled telling him. "Let me just make one more announcement," Miura told him. The colleague left for the roof and never saw Miura again.

When the disaster hit, Miura's wife Hiromi was working in an office about 20 kilometers north of her husband's workplace. She returned home and then took refuge on a nearby mountain, exactly as her husband's voice was telling her to over the broadcast system. But the next thing she knew, the broadcasts had stopped. "He must've escaped," Hiromi told herself. But she was not able to get in touch with Takeshi and when the community broadcasts returned the next day, it was a different voice. "He's not the type of person who asks someone else to do his job," Hiromi recalled thinking. The thought left her petrified with worry.

On April 11, a month after the earthquake, Hiromi was at the town office searching for anything that would help her find her missing husband. She stood among the debris, shouting his name as she cried. "I had a feeling he'd come back with a smile on his face and say, 'Phew, that was hard.' But it doesn't seem like that's going to happen," Hiromi said as she looked up through the rain at the building's wrecked skeleton.

Endo, 24, was manning the microphone, warning residents about the tsunami until she was relieved by Miura. On the afternoon of March 11, Endo's mother, Mieko, was working at a fish farm on the coast. While she ran to escape the tsunami, she heard her daughter's voice over the loudspeakers. When she came to her senses, Mieko realized she could not hear her daughter's voice.

Mieko and her husband Seiki visited all the shelters in the area and picked through debris looking for their daughter. Endo was assigned to the risk management section just one year ago. Many local people have thanked Mieko, saying her daughter's warnings saved their lives. "I want to thank my daughter [for saving so many people] and tell her I'm proud of her. But mostly I just want to see her smile again," Seiki said.

72 Lost Volunteer Firefighters Responsible for Gate-Closing

Of 253 volunteer firefighters who were killed or went missing in three disaster-hit prefectures as a result of the March 11 tsunami, at least 72 were in charge of closing floodgates or seawall gates in coastal areas, it has been learned. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 18, 2010]

There are about 1,450 floodgates in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures, including some to prevent the inflow of seawater into rivers and seawall gates to allow people to pass through. According to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry, 119 volunteer firefighters died or went missing in the March 11 disaster in Iwate Prefecture, 107 in Miyagi Prefecture and 27 in Fukushima Prefecture.

Of these, 59 and 13 were in charge of closing gates in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, respectively, according to a Yomiuri Shimbun survey of the municipalities and firefighting agencies concerned. Volunteer firefighters are classified as irregular local government officials, and many have regular jobs. Their average annual allowance was about $250 in 2008. Their allowance per mission amounted to $35 for the same year. If voluntary firefighters die in the line of duty, the Mutual Aid Fund for Official Casualties and Retirement of Volunteer firefighters pays benefits to their bereaved families.

In six municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture where volunteer firefighters were killed, the closing of gates was entrusted to private companies and citizen groups. A local resident of Namiemachi in the prefecture died after he went out to close a floodgate. According to the municipalities concerned and the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, volunteer firefighters were also swept away while guiding the evacuation of residents or while in transit after finishing gate-closing operations.

Of about 600 floodgates and seawall gates under the administration of the Iwate prefectural government, 33 can be remotely operated. However, in some cases, volunteer firefighters rushed to manually close gates because remote controls had been rendered inoperable due to earthquake-triggered power outages.

"Some volunteer firefighters may not have been able to close the seawall gates immediately because many people passed through the gates to fetch things left behind in their boats," an official of the Iwate prefectural government said. In Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, four volunteer firefighters trying to close gates fled from the oncoming tsunami, but three died or went missing.

Another factor that increased the death toll among volunteer firefighters was the fact that many did not possess wireless equipment, the Fire and Disaster Management Agency said. As a result, they could not obtain frequent updates on the heights of tsunami, it said.

Firefighters That Died in Kamaisha and Miyako

Tomoki Okamoto and Yuji Kimura wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Although volunteer firefighters are classified as temporary local government employees assigned to special government services, they are basically everyday civilians. "When an earthquake occurs, people head for the mountains [due to tsunami], but firefighters have to head toward the coast," said Yukio Sasa, 58, deputy chief of the No. 6 firefighting division in Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture. [Source: Tomoki Okamoto and Yuji Kimura, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 18, 2011]

The municipal government in Kamaishi entrusts the job of closing the city's 187 floodgates in an emergency to the firefighting team, private business operators and neighborhood associations. In the March 11 tsunami, six firefighters, a man appointed fire marshall at his company, and a board member of a neighborhood association were killed.

When the earthquake hit, Sasa's team headed toward the floodgates on the Kamaishi coast. Two members who successfully closed one floodgate fell victim to the tsunami--they were most likely engulfed while helping residents evacuate or while driving a fire engine away from the floodgate, according to Sasa."It's instinct for firefighters. If I'd been in their position, after closing the floodgate I would've been helping residents evacuate," Sasa said.

Even before the disaster, the municipal government had called on the prefectural and central governments to make the floodgates operable via remote control, noting the danger aging firefighters would face if they had to close the floodgates manually in an emergency.

In Miyako in the prefecture, two of the three floodgates with remote control functions failed to function properly on March 11. As soon as the earthquake hit, Kazunobu Hatakeyama, 47, leader of the city's No. 32 firefighting division, rushed to a firefighters' meeting point about one kilometer from the city's Settai floodgate. Another firefighter pushed a button that was supposed to make the floodgate close, but they could see on a surveillance monitor that it had not moved.

Hatakeyama had no choice but to drive to the floodgate and manually release the brake in its operation room.He managed to do this and close the floodgate in time, but could see the tsunami bearing down on him. He fled inland in his car, barely escaping. He saw water gush out of the operation room's windows as the tsunami demolished the floodgate.

"I would've died if I'd left the room a little bit later," Hatakeyama said. He stressed the need for a reliable remote control system: "I know there are some things that just have to be done, regardless of the danger. But firefighters are also civilians. We shouldn't be asked to die for no reason."

Japanese Kindergarten Ordered to Pay $1.8 Million over Tsunami Deaths

In September 2013, Peter Shadbolt of CNN wrote: “In the first ruling of its kind in Japan, a court has ordered a kindergarten to pay almost $2 million to the parents of four of five children who were killed after staff put them on a bus that drove straight into the path of an oncoming tsunami. Sendai District Court ordered Hiyori Kindergarten to pay 177 million yen ($1.8 million) to the parents of the children killed in the aftermath of the 2011 mega-quake that measured 9.0 on the Richter scale, according to court documents. [Source: Peter Shadbolt, CNN, September 18, 2013 /*]

Chief judge Norio Saiki said in the verdict that staff at the kindergarten in Ishinomaki city, which suffered widespread destruction in the March, 2011, disaster, could have expected a large tsunami from such a powerful quake. He said the staff did not fulfill their duties by collecting sufficient information for the safe evacuation of the children. "The kindergarten head failed to collect information and sent the bus seaward, which resulted in the loss of the children's lives," Saiki was quoted as saying on public broadcaster NHK. /*\

In the verdict he said the deaths could have been avoided if staff had kept the children at the school, which stood on higher ground, rather than sending them home and to their deaths. The court heard how staff placed the children on the bus which then sped seaward. Five children and one staff member were killed when the bus, which also caught fire in the accident, was overtaken by the tsunami. The parents had initially sought 267 million yen ($2.7 million) in damages. Local media reports said the decision was the first in Japan that compensated tsunami victims and was expected to affect other similar cases. /*\

Kyodo reported: “The complaint filed with the Sendai District Court in August 2011 said the school bus carrying 12 children left the kindergarten, which was located on high ground, about 15 minutes after the massive earthquake on March 11 for their homes along the coastline — despite a tsunami warning having already been issued. After dropping off seven of the 12 children along the way, the bus was swallowed by tsunami that killed the five children still on board. The plaintiffs are the parents of four of them. They accuse the kindergarten of failing to gather appropriate emergency and safety information via the radio and other sources, and for not adhering to agreed safety guidelines under which the children were to stay at the kindergarten, to be picked up by their parents and guardians in the event of an earthquake. According to the plaintiff’s lawyer, Kenji Kamada, another bus carrying other children had also departed from the kindergarten but turned back as the driver heard the tsunami warning over the radio. The children on that bus were not harmed. [Source: Kyodo, August 11, 2013]

Kids Killed in Tsunami Graduate Posthumously

In March 2013, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Friends and relatives sobbed uncontrollably when the principal of a middle school read out the names of four students who died in the tsunami after the Great East Japan Earthquake during a graduation ceremony Saturday in Natori, Miyagi Prefecture. The graduation ceremony of Yuriage Middle School was held at a temporary school building in the city about 10 kilometers from the coast. Of 14 students of the school who died in the March 11, 2011, tsunami, two boys and two girls would have attended the ceremony as graduates Saturday. Middle school diplomas were given to the families of the four, who became victims of the tsunami when they were first-year students. "My life totally changed after I lost my friends. I wanted to make lots of memories with them," a representative of the graduates said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 10, 2013]

Image Sources: 1) German Aerospace Center; 2) NASA

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, Daily Yomiuri, Japan Times, Mainichi Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2019