NOH THEATER

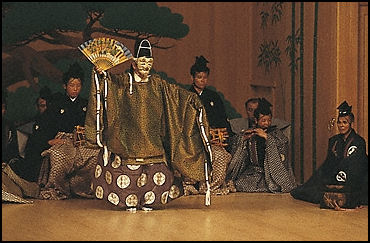

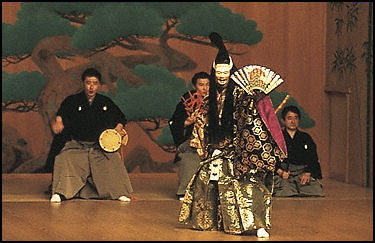

Noh actor by Akitoya Terada Noh is a stylistic form of musical dance-drama featuring elaborate masks. One of the main differences between kabuki and Noh is that in Noh the performers wear masks and in kabuki actors cover their face in white paint and make up. Noh (also spelled No) is regarded as beautiful but boring than kabuki because the actors wear elaborate costumes but the movements are slower and the action is more esoteric. In 2001, Noh was designated by UNESCO as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

“Noh” and its sister art form “kyogen” are two of Japan’s four forms of classical theater, the other two being “kabuki” and “bunraku”. “Noh”, which in its broadest sense includes the comic theater “kyogen”, developed as a distinctive theatrical form in the 14th century, making it the oldest extant professional theater in the world. Although “noh” and “kyogen” developed together and are inseparable, they are in many ways exact opposites. “Noh” is fundamentally a symbolic theater with primary importance attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied aesthetic atmosphere. In “kyogen”, on the other hand, primary importance is attached to making people laugh. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Noh (no) is regarded as one of the great classical traditions of world theater. Its wooden stage structure, its extremely slow and measured acting technique, grandiose costuming, beautiful masks, and minimalistic music have all been preserved more or less in the same form as they were perfected in the Muromachi period (1333–1568). Noh plays are known for their strength and other-worldly poetic beauty. They are admired around the world and many of them have been translated into several languages. Noh evolved in the refined court circles in Kyoto and in the upper echelons of the samurai class. Thus it is no wonder that Noh created sophisticated aesthetic theories, which one of its originators, the actor and playwright Zeami, formulated in his treatises. In fact, noh plays form only a part of a still more complex theatrical tradition, that of nohkagu. It combines the serious noh dramas with lighter kyogen farces. Traditionally a full, whole-day performance included five noh plays, interspersed by four kyogen farces. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Noh theater employs verse, prose, choral singing and dance to depict formal themes such as life and death, drama and illusion, and Zen Buddhist spirituality — based on religious tales and folk myths. The main characters are often military heroes and the ghosts of the people they killed who haunt them and seek revenge. The Noh performed today is virtually the same as Noh performed in the Middle Ages.

Thematically, Noh has tended to have strong supernatural elements. Stylistically, it is very structured with nearly all the movements being tightly choreographed. Visually, Noh features very austere stage sets and sumptuous costumes and dramatic masks.

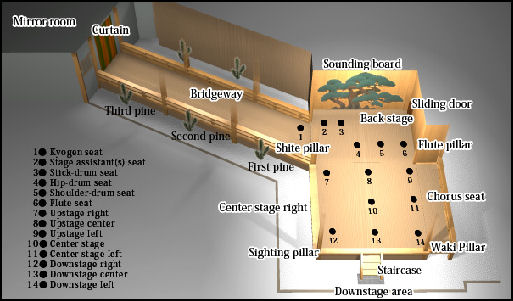

Until the late 1800s, Noh was performed in the open air in gazebo-style stages on the ground of temples. In the Meiji period drive toward Westernization Noh was moved indoors into to a theater with a peaked roof supported on four pillars. The square stage is made of cypress wood. The main actors make their entrance on a “hashi-gajkari” bridge lined with pine trees. The only adornment is a pine tree painting that serves as the universal background and evokes the days when performances were held outside.

Good Websites and Sources: Japan Arts Council www2.ntj.jac.go.jp ; Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Noh and Kyogen web-jpn.org/museum ; Noh and Kyogen Fact Sheet pdf file web-japan.org/factsheet ; Noh Mask Gallery noh-mask.hp ; No Mask Home Page nohmask21.com ; Noh Links meijigakuin.ac.jp/~watson ; No Plays. Etext, University of Virginia etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/noh ; U.S.-Based Theatre Nohgaku theatrenohgaku.org ; Noh Plays the-noh.com ; Books: ”The No Plays of Japan” by Arthur Ealey (Tuttle, 1976); “A Guide to No” by P.G. O'Neil (Hinoki Shoten, 1954). A variety of guides and booklets are also available from the Japanese National Tourist Office (JNTO) and Tourist Information Centers (TIC).

Noh Theater in Kyoto Kyoto Travel Kyoto Travel . Noh and kyogen are performed at the Osaka No Kaikan. A new Noh theater, the Kongo Noh Theater (five minutes by foot from Imadegawa subway station), opened in Kamigyo Ward in June 2003. Replacing the wooden Kongo Nogaku-do Theater which closed down after 140 years in 2000, it is a 430-seat concrete theater with computer-controlled lighting, a stage close to the audience, carefully-engineered acoustics and a headset system so that non-Japanese can follow the action in six languages. Noh and kyogen are also performed at the and the Kanze Nogaku-do Kaikan. Kyoto Travel Kyoto Travel Tokyo Noh and kyogen are performed at the National Noh, Kanzae Nogaku-do and Tessnkai Nogaku Institute theaters and at the Yarai Noh Stage (☎ (03)-3267-7311) near the Yarai exit of Kagurazaka Station on the Tozai subway line in Shinjuku ward. The National Noh Theater has a new English subtitle system which uses screens like those found on the backs of some airplane. Kabuki and Noh are staged throughout most of the year at the National Theater and the 1,900-seat Kabukiza Theater in Ginza. These days theaters with kabuki and noh performances provide synopses written in English and earphone guides, with detailed English translations that coincide with the action, to help foreign observers.

Links in this Website: NOH THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KABUKI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUNRAKU, JAPANESE PUPPET THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KYOGEN, RAKUGO AND THEATER IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TAKARAZUKA, JAPANESE ALL-FEMALE THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS AND THE MODERN WORLD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FOLK MUSIC AND ENKA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DANCE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Early History of Noh Theater

Edo period Noh Noh is one of the world's oldest continually-performed types of theater and the oldest of Japan’s traditional performing arts. It has it roots in mime, acrobatics and “sarugaku” (literally "monkey music"), a form of dance-drama associated with agriculture, from the early Heian Period (794-1185) and has had some links to China. In the early days, performers came from the lower classes and served as both entertainers and as performers of religious ceremonies.

Some scholar suggest that noh grew out of gigaku, a form of comical, silent drama where the actors wear different masks, and there's musical accompaniment from percussion and flute. In 752, a magnificent ceremony was held to consecrate the new Buddha statue in Nara. A gigaku play was also performed. A 7th century gigaku mask in the Shoso-in collection depicts a ruddy-faced foreign king who lead a group of drunken men. It’s high bridged- nose and other strong features have led some to speculate the king was supposed to be a Persian. Gigaku is thought to have originated in the Wu kingdom of ancient China and was introduced to Japan by the Paekche kingdom on the Korean peninsula.

Noh was performed at Kofukuji Temple in Nara in A.D. 869 during Buddhist Shunie ceremonies to pray for national prosperity. Ishun Moriya, a senior priest at the temple, told the Daily Yomiuri, “The performance contained many mystical elements in the earliest days because they were performed by Buddhists priests to thank Buddha for warding off evil...Gradually the spectrum broadened to include more entertaining elements. Noh plays featuring Buddhist rituals came to be performed by professionals, and the spectacle’s reputation spread among nobles and others...These performers received handsome benefits from the elite administrators because their enrichment of the temple’s rituals was highly valued.”

Noh was traditionally performed at Buddhist temples. The use of masks and the frequent appearance of ghosts is based in the fact that Noh originated in a time of war and upheaval when many people were preoccupied with death and the afterlife.

Later History of Noh Theater

Noh settled into its present form around the 14th century. In the mid 14th century noh was dominated by humorous and entertaining plays known as “sarugaku” or “sangaku”. The pioneers of the Noh form were the playwright Kanami (1333-1384) and his son, Zeami (1363-1443). The first Noh performances was when 12-year-old Zeami and Kanami danced sarugaku in front of the 18-year-old shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu in 1374 in Kyoto. Under the patronage of Yoshimitsu, Zeami and Kanami developed Noh by incorporating elements of their performing arts, poetry and classical and current topic into the dance.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “New noh schools evolved to cultivate noh in its classical form, perfected by Zeami. Noh was amalgamated with kyogen farces, and the new combination was called nohgaku. Remarkable playwrights enriched noh’s repertoire and the patronage of the samurai class continued while even some of the shoguns themselves appeared on the Noh stage.[Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

According Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions were touring and performing at temples, shrines, and festivals, often with the patronage of the nobility. The performing genre called “sarugaku” was one of these traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors Kan’ami (1333-1384) and his son Zeami (1363-1443) transformed “sarugaku” into “noh” in basically the same form as it is still performed today. Kan’ami introduced the music and dance elements of the popular entertainment “kuse-mai” into sarugaku”, and he attracted the attention and patronage of Muromachi “shogun” Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance to further refine the “noh” aesthetic principles of “monomane” (the imitation of things) and “yugen”, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing the suggestion of mystery and depth. In addition to writing some of the best-known plays in the “noh” repertoire, Zeami wrote a series of essays which defined the standards for “noh” performance in the centuries that followed. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Noh became the official art form of the samurai class and enjoyed by famous Japanese historical figures such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotimi Hideyoshi. After the fall of the Muromachi shogunate, “noh” received extensive patronage from military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and in the 17th century “noh” became an “official property” of the Tokugawa shogunate. During these years, performances became even slower and more solemn than in Zeami’s time. In the Edo Period (1603-1868), a single Noh performance could take up an entire day and themes were often things close to samurai’s heart, such as honor, duty and revenge and Zen austerity.

Miettinen wrote: During the Edo period (1608–1868) noh also continued to be the art of the samurai class, although in the new cultural climate some commoners also became its patrons. Gradually noh also came to be known outside the noble samurai circles, for example, in the form of temple performances. The old feudal world crumbled at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912) and Noh lost its original patronage. Noh was not regarded as fashionable amid the new, western-influenced forms of entertainment. However, owing to the support of the imperial family, noh did not completely die out. Continuation of the tradition was secured in 1881 when the Noh Society was founded. Noh has now also gained new popularity, particularly among educated audiences, both in Japan and in the West. **

With the fall of the shogunate, “noh” in the Meiji period (1868-1912) was kept alive by the dedication of performers like Umewaka Minoru I (1828-1909) and by the patronage of the nobility. Since the end of World War II, “noh” has had to depend entirely on the public for its survival. “Noh” today continues to be supported by a small but dedicated group of theatergoers, and by a considerable number of amateurs who pay for instruction in “noh” singing and dancing techniques. In recent years “noh” performed outdoors at night by firelight (called “takiginoh”) has become increasingly popular, and there are many such performances held in the summer at Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, and parks.

Five schools of Noh are still in existence. The humorous forms of sarugaku survived as an independent art form that came to be known as kyogen, which has traditionally been performed in the intervals between Noh plays. (See Separate article on Kyogen).

Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his Son Zeami (1363–1443)

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The actor and playwright Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami (1363–1443) are regarded as the inventors of noh. The new art form was not, however, created from the void. Several other forms of entertainment were popular during the time when noh gradually got its shape. Among the early forms of theater were sarugaku plays, which combined dance, music and mimetic acting. This rather light form of entertainment, which possibly originated in China, became the basis on which Kan’ami and Zeami then shaped their austere novelty, noh. Another root tradition for noh was dengkaku, a versatile genre of entertainment that had its roots in rice-planting songs as well as in ancient fertility rites and spirit possession. It gradually evolved into popular forms, which blended music, singing, dancing, and mime. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

When the shogun’s court was moved to Kyoto, Kan’ami founded his school there. It was named after his stage name, Kanze. There he started to refine the melodies of sarugaku and the energetic rhythms of dengkaku. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shogun of the period, became an admirer of noh. This heralded the long tradition of noh’s patronage by the uppermost samurai class. Zeami, Kan’ami’s son, was only twelve years old when he performed for the shogun for the first time. The shogun took Zeami under his protection and they became close friends. Thus Zeami was raised to the highest level of the social hierarchy. **

Without any doubt, Zeami is the most remarkable individual in the whole history of noh. First of all, he was regarded as the topmost actor of his time. Furthermore, he was a very productive playwright and, besides that, he was also a choreographer, musician, and stage director. Zeami also formulated the sophisticated theory of noh in his treatises, which will be discussed later. After the death of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Zeami’s popularity at court declined. When he was an old man he was finally exiled to a remote island, where he is believed to have died. **

Zeami wrote many noh scripts and books on dramatic theory. His Fushi Kaden and other dramatic treatises have been translated into foreign languages and continue to influence many people involved in theater worldwide. Fushi Kaden, a masterwork, is particularly acclaimed in the world of drama history, as it describes the theater training process and the essence of the performing arts using comparisons to flowers. The noh master Kanze said he often refers to Fushi Kaden. “It includes dramatic theory and also Zeami’s view of life,” he said. “Like his noh pieces, the theory is always questioning what it is to be human and what life is. It contains many good axioms and maxims, so I hope people read it.” [Source: Junichiro Shiozaki, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 11, 2013]

Aesthetic Theories of Noh

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Besides noh dramas, Zeami, the great exponent of noh, also wrote acting treatises. Originally they were secret writings for the members of his noh school, but they most probably also circulated among the patrons of noh, that is, among the members of the upper samurai class and thus shaped the general aesthetics of the period. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The treatises, which became generally known only at the beginning of the 20th century, give unique inside information about the religious-philosophical aspects of noh and serve today as an extremely valuable source for students of Japanese aesthetics. Zeami’s treatises include, among other things, Fushikaden or the “Transmission of Style and the Flower”, Kadensho or the “Communication of Flower Acting”, and Shikado or “The Path to the Flower”. **

Zeami regards noh as The Way. Thus noh, in a similar way as meditation or Zen Buddhist calligraphy and ink painting, can serve as a vehicle for a sudden “realisation”, which opens up the path to nirvana. Furthermore, he regarded noh performances as prayers for peace and prosperity. According to Zeami, noh is a combination of three elements: 1) role-play or imitation; 2) poetic chanting; and 3) music. **

Zeami also discusses the term hana or flower. It has several meanings, for example, the highest artistic achievement, the mysterious radiation of art etc. An actor must reach hana, although it varies according to his age. According to Zeami, hana can only be experienced when there are secrets; without them there is no hana. In order to reach hana the actor must work constantly through his whole life. In acting there must be, according to Zeami, “bone”, “flesh” and “skin”. By bone he means natural talent, flesh refers to learned skill, while skin means the impression of easiness, which finally creates beauty. **

Noh Contents and the Language

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Although there are some more recent noh plays, most of them deal with the ethical dilemmas of the samurai class of the period when the plays were written. A basic conflict is created by the two completely opposite ideologies of the period, i.e. the pacifistic Zen Buddhism and the strict code of ethics of the members of the samurai class, who were trained warriors. Very often the plays contemplate on karmic questions, based on the Buddhist world-view, for example, on how a person must pay for his bad deeds before being liberated from being a ghost between this and the other world (read the synopsis of Tenko, one of the plays dealing with the liberation of a wronged soul). [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

A noh play may be based on a short episode picked up from classical literature, such as the Genji Monogatari, discussed above (read the synopsis of Lady Aoi). Many of the themes are adapted from the great epics of the feudal period, such as The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari) and the Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari). Anthologies of classical poetry also supplied themes for the plays. Thus the plays are full of references to classical poetry, Buddhist scripts, historical anecdotes, and even Chinese poetry. One characteristic of noh’s language is that there is rarely a sharp distinction between poetry and prose. **

To understand the noh texts in all their depth required the highest education in feudal Japan. As the plays were intended for the samurai elite and the court circles, the period’s highly formal etiquette and courteous way of speaking are also reflected in the language. A simple question (“What is your name?”, for example) requires seven words to be politely asked in a noh play. It is no wonder that only a very few members of modern audiences completely understand the texts and their complicated language. That is why most spectators today take with them a kind of guide booklet, in which the symbolism and the literary allusions are explained. **

Music and the Chorus

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The music of noh was refined from older musical traditions. Music in noh does not “accompany” the action as is often the case in Western forms of music theater. In noh, music forms an aural level of its own, which rarely, and mainly only in the climaxes, exactly matches the action on the stage. A small orchestra and a chorus accompany or, maybe more correctly, give their aural addition to the performances. The musicians and the chorus singers are collectively called hayashi kata. The musicians sit at the rear of the stage facing the audience, while the chorus sits to the right of the audience facing the stage and the action. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The instruments include a flute as the melodic instrument and three kinds of drums, the number of which may vary according to the requirements of the play. The notated music, like the structure of the play, follows the jo-ha-kyu principle discussed above. The music’s silent moments are emphasised, which creates an aural impression of space. The flute produces long melodic lines, which often seem to disappear into distance. Sharp drumbeats accentuate the time and build up the intensity and climaxes of the drama. The drummers also use their voices. They shout and howl, which fills the empty space between the beats. These calls, called kakegoe, have an important role in anticipating and underlining the dramatic action. **

The wooden stage also functions as a kind of instrument. The “mirror wall” behind the orchestra serves as an acoustic surface, which reflects the music towards the audience. In the climatic dance sequences the stage is used as a kind of drum when the actor loudly stamps the resonating wooden floor. The stamping sound is amplified by large pots hidden underneath the floor of the stage. **

Singing is done both by actors and the chorus. In fact, the lines of a character can be divided so that an actor sings part of it and the chorus the other part of it. In the noh songs, originally derived from ancient Buddhist chanting, the voice is kept very low, regardless of whether the character is male or female. The vocal technique may sound, at the beginning, monotonic. In fact, the sung parts are performed with five different colourings. Roughly translated, they are the strong, the gentle, the dynamic, the longing, and the sad modes. **

Noh Actors

Noh features only male actors. A Noh troupe consists of the “tachikata” (performers who don masks, act and dance) and the “hayashikata” (musicians who are in charge of beating time and intensifying the emotional atmosphere of the play). Some Noh roles are regarded as so special that Noh actors are only allowed to play them once in their lifetimes. A typical Noh performance employs three or four musicians. Traditional instruments in the Noh wind and percussion ensemble include the “nakan” (a vertical flute) and “tsuzumi” (small hand drums). The musicians sometimes shout and sing when they perform. Big clay pots are placed sin hollow spaced beneath the wooden stage to amplify sound, mainly footsteps and drumming.

There are two main types of Noh actors: the “shite” (the one who acts) and the “waki” (the one who watches). The main characters are shites who usually wear masks. They are generally a supernatural being such as ghosts, demons, gods or ghosts — or a woman. Waki nether wear a mask or make up because they represent living, breathing men.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The actors of a certain play are categorised, not according to the character or character type they are embodying, but according to the role or importance of the character in the structure of the play.The actors are categorised as: 1) Shite or the principal character, who often appears masked; 2) Waki or the supporting role, who is always an unmasked human being; 3) Shite-zure actors perform the roles of shite’s companions; 4) Waki-zure actors represent waki’s companions; 5) Kokata, or child roles, are performed by boy actors.This system does not mean that an actor specialises in one of the above categories. In fact, an actor can appear in any of the role types (except kokata). Besides that, he can also sing in the chorus, which forms an integral element of a noh performance.[Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

In 1948 the first Noh actress appeared, In 2004, the first women were made members of the Nihon Nogaku-kai, which means they are officially recognized as professional Noh performers. In 2005 a play was performed called “Onna ni yoru Onna no tame no Onna Noh” (“Women’s Noh — Played by Women for Women”) based on episodes from “The Tale of Genji”.

Noh Acting Technique

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The music of noh was refined from older musical traditions. Music in noh does not “accompany” the action as is often the case in Western forms of music theater. In noh, music forms an aural level of its own, which rarely, and mainly only in the climaxes, exactly matches the action on the stage. A small orchestra and a chorus accompany or, maybe more correctly, give their aural addition to the performances. The musicians and the chorus singers are collectively called hayashi kata. The musicians sit at the rear of the stage facing the audience, while the chorus sits to the right of the audience facing the stage and the action. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The acting technique of noh is characterised by its slowness and measured precision. All the elements unnecessary for the drama are eliminated. This gives noh its crystalline, almost hypnotic quality. In the noh standing position the body, with a straight back, leans slightly forward while the chin is pointed towards the throat. The arms curve slightly forward while the hands are kept in a fixed closed position in which the fingers are motionless. **

The stylised, sliding noh walking is called hakobi. The soles of the feet, covered with white socks, are rarely lifted from the floor. The knees, hidden by the heavy costuming, are kept slightly bent, which enables the actor to slide on the stage floor without any visible vertical movements. Male characters have a slightly open standing position, while female characters keep their feet closer. The slightly bent positions of the knees and the back make it possible for the actor, in a way, to “grow” on the stage. During a dramatic moment, for example in connection with a fateful revelation, the actor may straighten up, creating a stunning impression of growing in size. **

The dance sequences of noh, called mai, form the climactic highlights of many of the plays. The noh dances are extremely minimalistic in their movements. The dance sections are very archaic in character, limited to a few circling movements, changes in the sculpturesque body positions, and some hand movements. The dance finally culminates in powerful stamping steps. **

Five Schools of Noh

Contemporary noh is dominate by five major troupes, all of which have many groups that follow their styles. Four are based in Tokyo and one is based in Kyoto. Four of these troupes — Konparu, Hosho, Kigo and Kanza — where founded in the 14th century and were based in the Yamato region of Nara. Most actors are trained in family run schools. There are currently only four schools (three in Tokyo and one in Kyoto). Many famous actors come from Noh families and make their first appearances when they are 4 or 5.

Noh is still performed today and taught mainly by five “schools” or actor lineages, which were founded over the centuries by important individual actors. The schools are the Kanze, Hosho, Konparu, Kongo and Kita Schools. The most prestigious of them is the Kanze School, as it was founded by Kan’ami, the first exponent of the whole art form. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Usually all the professional noh performers belong to one of the five schools. As the profession is, to a great extent, still a hereditary profession, the artist’s role in the noh tradition depends on his family relationship within the actors’ lineage. Normally a performer joins the same school as his father, who thus trains the next generation. Within a noh school the highest authority belongs to the head of the family, who directs and advises other members of the family/school throughout their careers. Thus noh forms a well-guarded, closed world of its own. Outsiders may, though, practise and even perform some of its aspects, such as noh songs and dances. **

Noh Masks

Many people, both in Japan and abroad, who have little or no direct knowledge of “noh” theater have nevertheless come into contact with “noh” through its famous masks, which are often shown in museums and special exhibitions. The elaborate masks in Noh theater are usually expressionless, which means that it is the responsibility of the actor to convey emotion through body movements. Joy and sadness can be expressed with the same mask through a slight change in the way shadows fall across its features. The masks represent the characters minds and hearts and trace their origins back to exorcism and rice planting rites. Noh masks have been used by engineers developing robots that respond accurately to human facial expressions.

Specific masks are associated with specific characters. A devil-like, horned mask, for example, is worn by an actor playing Hannya, the jealous, revengeful demon who was once a beautiful woman. The many mask variations fall into several general types, such as young woman, old man, and demon, and even among masks used for the same role there are different levels of dignity (“kurai”) which affect how the role and play as a whole are to be performed. Usually only the leading character (“shite”) wears a mask, though in some plays a mask is also worn by accompanying characters (“tsure”). Subordinate characters (“waki”), their accompanying characters (“wakitsure”), and child characters (“kokata”) do not wear masks.

There are around 60 basic masks each with their own name. Some have variation. If these are included there about 200 different types. Some schools have their own masks which are hundreds of years old. In the old days the masks were made from paulownia or camphor but today most are made from “hinki” cypress because it has few knots and a straight grain.

The masks are carefully made with a lack of symmetry in the features. They are painted with three or four layers of a pigment made of ground seashell and animal glue an then sandpapered. These steps are repeated several times so create a smooth surface. Shading is achieved using brown pigments made from soot boiled in rice wine, Most facial features are painted with India ink. The teeth were often black (blackened teeth were a fashion statement in Japan until the 19th century). Masks for supernatural being have gold dust mixed with glue. The back of the mask is painted red, waxed, and chemically burned. The art making masks has been passed down over generations from father to son.

The oldest wooden mask in Japan was found in the Makimiku ruins Sakurai, Nara. Used perhaps in an agricultural ceremony that influenced Noh, it was carved with a farming hoe in the early A.D. 3rd century. The masks is 21.5 centimeters long and 31,5 centimeters wide and has no holes for straps which indicated it was probably held up with hands,

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The extremely measured and minimalistic noh acting technique, which has been discussed above, seems partly to stem from the strict court etiquette of the periods when noh theater was shaped. According to the etiquette, facial expressions were regarded as vulgar. So too in noh, those actors who do not wear masks keep their faces completely expressionless. However, the measured movements may be partly due to the use of masks. By slightly altering the angle of his head, the actor is able to change the mask’s expression. When the angle of the mask is adjusted, its expression seems to change from happiness to sorrow etc. This is possible because the expression of most of the masks reflects a certain neutral ambiguity, which allows the audience to make several interpretations. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The noh masks were developed from earlier Japanese mask systems. Compared, for example, with the wooden gigaku masks, the Noh masks are smaller, as they cover only the central part of the actors’ faces. Old noh masks are regarded as valuable works of art. They have been preserved and used by generations of noh families and their schools. Masks are worn by several of the shite characters, as well as some of the sure companion characters. Most of the masks are character masks, for example those of a young woman, an old woman, a middle-aged samurai, a young aristocrat etc. However, some of the masks are reserved for particular roles. **

Before going onto the stage, the actor adjusts the mask on his face in the adjoining “mirror room”, where he then contemplates the role he is going to perform. Small cushions fastened to the back of the mask ensure that the basic angle of the masks will be correct, regardless of the physiognomic differences in the actors’ facial features. **

Noh Costumes

16th century Noh robe Along with its masks, “noh” is also known for its boldly patterned extravagant costumes, which create a sharp contrast with the bare stage and restrained movements. A “shite” costume with five layers and an outer garment of rich brocade creates an imposing figure on stage, an effect that is heightened in some plays by the wearing of a brilliant red or white wig. The ability of the “shite” and “waki” to express volumes with a gesture is enhanced by their use of various hand properties, the most important of which is the folding fan (“chukei”). The fan can be used to represent an object, such as a dagger or ladle, or an action, such as beckoning or moon-viewing. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Noh costumes are very lavish and elaborate. In the old days they were taken care of by nobility and guarded by the military. The costumes have a basic straight line cut and consist of a knee-length padded silk robe worn with a small pillow to give the abdomen a rounded look; a long stiff divided skirt and outer robe. Different robes or worn by the male and female characters. Accessories include wigs and fans.

The way the garments are worn often has a special meaning, the right sleeve flipped off and dropped over the performer’s back, for example, indicates active movement or madness. An outer robe tacked onto the pants indicates a lady of the court. If a considerable amount of dancing is done lighter garments are worn. Dressers are generally a thing of the past the actors generally dress each other.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The gorgeous costuming of noh follows the practices of the court circles of the Muromachi period. It is believed that in the very early stages of noh’s history the costumes were simpler. Just like the masks, the sophisticated brocade robes of the noh costumes are also regarded as valued works of art. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The costumes (shozoku) are full of symbolism, and the guide booklets, which many of the spectators use to follow the performances, often include explanations of the meanings of the costumes and their ornamented details. There are some specific forms of costumes characteristic of noh. They include, among other things, the very wide, folding trousers of some of the male characters and the highly ornamented colourful robes of many of the female characters. With his wig and complicated costume a noh actor is almost like a living sculpture. Thus the perfect order of the draperies and the hair are of upmost importance. That is why stage assistants appear every now and then on the stage to straighten the wig and the costume. **

Noh Stage and Props

The “noh” stage, which was originally outdoors but is now usually located within a larger structure, is itself a work of art. The main stage, measuring six by six meters, is built of polished Japanese cypress (“hinoki”) and covered by a magnificent Shinto-style roof, and there is a bridge (“hashigakari”) that serves as a passageway to the stage. To the right and rear of the main stage are areas where the musicians and chorus sit. The pine tree painted on the back wall serves as the only background for all plays, the setting being established by the words of the actors and chorus. The three or four musicians (“hayashikata”) sit at the back of the stage and play the flute, the small hand drum (“kotsuzumi”), the large hand drum (“otsuzumi”), and, when the play requires it, the large floor drum (“taiko”). The chorus (“jiutai”), whose main role is to sing the words and thoughts of the leading character, sits at the right of the stage. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Only in a few forms of Asian theater does the stage structure form such an integral element of the whole art form as is the case in noh theater. The oldest existing noh stages are outdoor structures, built some three hundred years ago in the courtyards of Zen monasteries. Nowadays the stage structures follow exactly the same model, although they are now most often erected in indoor halls. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The stage itself is a wooden platform of some six meters square. The stage has an extension for the chorus on the right side of the audience, and at the rear an extension for the musicians. On the left there is a bridge or a walkway (hasigagari), which connects the stage with the backstage area. Immediately after the bridge there is the so-called “mirror room”, in which the actors adjust the masks on their faces. The “mirror room” is separated from the walkway by a small colourful curtain. **

Behind the stage, facing the audience, is a wooden wall, always decorated with a large painting of a twisted pine tree. The wall reflects the music towards the audience, while the painted pine tree and painted bamboos on the side walls remind one of the time when noh was performed outdoors. An elegant reference to Zen Buddhist aesthetics and garden planning is given by the narrow strips of white gravel with miniature pine trees in front of the stage. In a similar way the stage’s unpainted wooden structure with its high roof also reflects the spirit of Zen architecture. The colour of the wood varies from a natural shade to a reddish colour and further to dark patina. The shades give each stage its particular atmosphere. **

Props are used sparsely. The most important prop the actor handles is a large fan. Larger stage props are, indeed, conceptual in character. If, for example, a pine tree is needed, the stage assistants bring to the stage a white framework to which a pine tree is attached. This basic framework may also serve as a carriage, a tower, a boat etc. **

Noh Performances

"Noh is essentially a form a religious theater with aesthetic coded defined by the austerities and minimalism of Zen." It combines music, dance, drama and instrumental music. Unlike kabuki, which emphasizes grand gestures and spectacle, Noh gets its punch from subtlety and understatement. The sets are usually empty of props and the masks are intended to keep facial expressions from performers who aim to express themselves through slow movement that are regarded by admirers as economical but powerful.

A traditional “noh” program included five “noh” plays interspersed with three or four “kyogen”, but a program today is more likely to have two or three “ noh” plays separated by one or two “ kyogen”. Both the program and each individual play are based on the dramatic pattern j” “o-hakyu” (introduction-exposition-rapid finale), with a play usually having one “jo” section, three “ha” sections, and one “kyu” section.

A typical performance features a shite, a waki, four musicians at the back and eight chorus members slightly off stage left. The story is relayed by the chorus, accompanied by the musicians. Junichiro Shiozaki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Hirotda Kamei, 37, is a leading performer of otsuzumi (also called okawa) in his generation. Otsuzumi is one of the four instruments used to keep time in noh. It's clear, masculine sound, punctuated by the occasional yell from the performer during a performance, are thoroughly enchanting. Kamei has followed in the footsteps of his father Tadao, a living national treasure and headmaster of the Kadono school of otsuzumi. Kamei is widely expected to become the school's next headmaster. "I aim to bring the energy emitted by the noh stage into harmony with the audience," Kamei said. [Source: Junichiro Shiozaki, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 2012]

Noh actors follow strictly prescribed footsteps and movements across the stage. In may ways, Noh is better appreciated as a form of visual art one contemplates and mediates over while watching rather than a performing art that is expected to be entertaining. Many Westerners artists, Y.B. Yeats in particular, were mesmerized by Noh and what it tried to do.

Noh is full of symbolism. In many Noh dramas the shite is spirit or ghosts who remains in one place because of some tragedy and role of the waki is to demask him. The demasking usually brings an end to the first act, with the second act being a recreation of the tragedy, which is can be a cathartic process or a painful one, depending on how the play is written or interpreted.

Pace and Rhythm of a Noh Performance

Sawa Kurotani wrote in The Japan News, “The classic three-story structure of jo-ha-kyu (beginning, break, climax) in noh theater breaks down the plot into 15 essential “beats” (key actions that move the story forward), which must happen at a specific points. For example, the “catalyst,” or the event that compels the protagonist to take action, must take place by Page 12; the “A” story unfolds between pages 12 and 30, the “B” story (on pages 30 to 55) escalates conflict, and after a period of trouble and reflection, the final story takes up the last 25 to 30 pages. [Source: Sawa Kurotani, The Japan News, July 9, 2013 /^/]

“In terms of the pace of storytelling, on the other end of the spectrum is the noh play Kantan. The beginning of the play (where a young protagonist in search of his destiny arrives at an inn in the city of Kantan, explains himself to the innkeeper, and takes a nap with a magical pillow while waiting for dinner) was so long and monotonous (so it seemed to me, at least) that I was practically in a coma when the “break” finally came. Eventually, the protagonist was awakened (though, actually, he was still dreaming) by a messenger who tells him he was chosen to be the next emperor. As the activity suddenly picked up, I was transfixed by the music and singing that was growing louder and faster, and—in retrospect—I had fallen into a sort of hypnotic state. /^/

“Then, suddenly, a loud “Bang!”—the sound of the innkeeper knocking on her guest’s wooden pillow to wake him—brought me back to reality, as the protagonist comes to realize his 50 years of imperial reign was just a dream. I enjoy well-crafted, lavishly produced Hollywood films like anybody else, but the kind of pleasure they provide can never replace that of the deceptively sedate noh play. /^/

Types of Noh Plays

There exist 240 noh plays. They are categorised according to their shite, or main characters. These include: 1) God Plays (Waki Noh) narrate stories about various gods or god-like beings. The shite actor usually wears a mask. At the beginning he often appears in disguise and reveals his identity only at the end of the play. 2) Warrior Plays (Shura Mono): The shite actor plays the role of a samurai or another warrior, who, after his death, has not found peace for his soul. Only after prayers from outsiders are his karmic deeds forgiven, and he is able to find final peace. 3) Wig Plays (Katsura Mono): In these lyrical plays the shite actor mostly plays a woman’s roles (read the synopsis of Hagoromo, one of the wig plays). 4) Miscellaneous Plays (Zatsu Mono): This group includes various plays which do not fit in the other categories, such as scripts dealing with ghosts or mad persons. 5) Closing Plays (Kiri No): The shite actor usually plays a demon role in these energetic plays. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

In their structure the plays follow a certain aesthetic principle, called jo-ha-kyu. It was derived from old court music with its roots in India. Jo refers to the beginning or introduction, and its tempo is slow. Ha refers to the middle part in which the actual dramatic situation is presented. In kyu, or the final part, the tempo of the action and the music quicken and the drama finally reaches its climax. **

In the introductory part of a play the waki and shite (often in disguise) appear separately and ceremoniously introduce themselves. Thus the ingredients of the drama are made clear. In the middle section the tempo of the performance becomes faster and the drama often climaxes in a stylised dance (mai) in which the shite recalls the past. In the finale, the shite returns to the stage and the dramatic action leads to its majestic end. **

The structure of a full-day noh performance should follow the jo-ha-kyu principle in a similar way, too. The opening play often represents the category of the “god plays”. The plays of the middle part of the performance represent the “warrior” or “wig plays”, while a play belonging to the category of “closing plays” ends the performance. **

Noh Plays

The “noh” repertoire is made up of “Okina”, which is only performed on special occasions and is more of a ritual dance than a play, and about 240 extant plays classified into five different groups. “The first group consists of the god plays (“waki noh”), in which the “shite” is first a human being and later a god. These plays, slow moving even by “noh” standards, are performed relatively seldom today. The second group is the warrior plays (“shuramono”). In most of these a dead warrior from the losing side in the Taira-Minamoto War pleads with a priest to pray for his soul. Wig plays (“kazura-mono”) represent the third group. These plays are often about a beautiful woman of the Heian period (794-1185) who is obsessed by love. The fourth group is the largest and is usually referred to as “miscellaneous “noh”” (“zatsu noh”) because plays on a variety of themes are included. The fifth and final group is the demon plays (“kiri-noh”). In these plays, which tend to be the fastest moving of all the groups, the “shite” often appears in human form in the first half and then reveals himself as a demon in the second half. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Tsuchigumo” (“The Ground Spider”) is a classic tale of brave warriors confronting a terrifying spider monster. The main character, Raiko, is based on a historical figure from about 1,000 years ago. The spider image is said to have originated from a disparaging term for indigenous people and is thus seen as a commentary on the way that Raiku may have treated indigenous people and the way the indigenous people rebelled. In the most dramatic seen four warriors attack the spider who responds by emitting threads that look like white washi paper fireworks. The slaying of the spider is seen as Raiku’s victory over the indigenous people.

“Okina”, the oldest play in the Noh repertoire, is rarely performed. “Hagoromo”, one of the classics of Noh theater, is about a fisherman that finds a beautiful robe hanging from a pine tree. When an angel comes to claim it, the fishermen refuses to turn it over. After being enlightened about the foolish ways of humans he reluctantly hands the robe over and is rewarded with a dance by the angel.

“Sesshoseki” (“The Life-Killing Stone”) is a famous Noh story about a monk that happens on a mysterious stone with no plants or living things around. A woman suddenly appears and tells the monk the stone contains the spirit of a woman who became an emperor’s concubine in a bid to overthrow the ruling dynasty and was killed and driven into the stone by a priest. The woman then revealed herself to be the spirit of the stone and asks the monk to pray for her so she can stop killing.

“Lady Senju” like many classic Japanese tragedies is based on an incident from the “Heike Monogatari” (“The Tale of the Heike”), an epic takes set during the 12th century when the Taira (Heike) and Minamoto (Genji) clans battled for control of Japan. In the story the hero Taira no Shigehara has been captured by the enemy and taken to Kyoto most likely to be put to death. Munemochi, a Minamoto retainer, take pity on him and sends the elegant courtesan Senju to entertain and console him for what might be his last night on earth. Most of the play’s action revolves around a banquet with sake and music and dancing prepared by Senju for Shigehira. In “Lady Senju” Senju and Shigehire make beautiful mimed music together on the biwa and koto. The only music heard comes from the flute and drums of the Noh musicians. A sexual union is suggested by a scene in which the pair face each other and hold fans, which symbolize pillows.

Other Noh Plays

Other include “Hibariyama”, a Snow-White-like tale of daughter sent in the forest by a servant ordered to kill her; “Utou”, the story of a hunter, who from the dead expresses remorse over all the animals he has killed; “Tome”, about a troubled mistress of a teenage warrior; and Kanawa, the story of a scorned woman who becomes an evil spirit and attacks her husband

Junichiro Shiozaki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Motokiyo Zeami (1363-1443), the founder of today's noh, sought subtle and profound beauty in his work, while Kanze Nobumitsu, a son of Zeami's nephew, is known for his brilliant style. Zeami, Nobumitsu and Zeami's son-in-law Komparu Zenchiku are typical noh creators, who are equal to Chikamatsu Monzaemon and Kawatake Mokuami in kabuki, Noh drummer Hirotada Kamei said. "Pieces created by Zeami are superior to Nobumitsu's regarding the depth of narrative. They make me think about life, nature and the universe. His pieces encourage me to reflect on my notions of life in my performance." On the other hand, Nobumitsu's pieces are visually brilliant and entertaining, Kamei said. "Their plots are simple and easy to understand.” [Source: Junichiro Shiozaki, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 2012]

“Kinuta” (“The Pressing Board”) by Zeami features a woman in the Kyushu region who dies while awaiting the return of her husband, who left to file a suit in Kyoto. The husband returns home at last to meet the departed soul of his wife. “Tamanoi” (“The Jeweled Well”) by Kanze Nobumitsu illustrates a dragon king at his palace at the bottom of the sea and his beautiful princesses.

Aoi no Ue( Lady Aoi)

The play “Aoi no Ue” (“Lady Aoi”) is one of the most frequently performed in the “noh” repertoire. The original author of the play is unknown; it was revised by Zeami and is based on events in the 11th-century novel “The Tale of Genji”, by Murasaki Shikibu. As the play opens, a court official (“wakitsure” role) explains that Lady Aoi, the pregnant wife of court noble Genji, is ill, and the sorceress Teruhi has been called in an attempt to identify the spirit possessing her. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“A folded robe placed at the front of the stage represents Lady Aoi. The sorceress (“tsure” role) summons the spirit possessing Lady Aoi. The spirit (“shite” role) approaches. (The “shite” wears the “deigan” mask used for vengeful female spirits.) It is Lady Rokujo, Genji’s neglected mistress. Speaking for herself and through the chorus, Lady Rokujo tells of the ephemeral nature of happiness in this world, and of her resentment toward Lady Aoi as the wife of the radiant Genji. (Lady Rokujo had been further humiliated when her carriage was pushed aside by that of Lady Aoi at a festival not long before.) The spirit of Lady Rokujo moves forward to strike Lady Aoi with her fan, and then moves to the back of the stage. There, shielded from the audience by a robe held by attendants, the “shite” changes from the “deigan” mask to the “hannya” female demon mask.

“The court official calls a messenger to summon a Buddhist mountain ascetic (“waki” role) to exorcise the spirit. After the exorcism rite begins, the “shite” returns to center stage, now wearing the demon mask and wielding a demon rod. They fight and the angry spirit of Lady Rokujo is overcome by the ascetic’s prayers. This triumph of Buddhist law and saving of Lady Aoi contrasts with “The Tale of Genji”; in the novel, Lady Aoi dies giving birth to Genji’s son.

Modern Noh Play About Zeami

Junichiro Shiozaki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, 2013 “is the 650th anniversary of the birth of Zeami, who brought noh to the zenith of its form, and the 680th anniversary of the birth of his father Kanami, a talented noh actor. In April 2013, a new noh piece highlighting the late years of Zeami’s life was staged at the National Noh Theater in Tokyo. Titled Super Noh: Zeami, its script was written by noted philosopher Takeshi Umehara, who also wrote scripts for Super Kabuki and Super Kyogen pieces, which blended many innovative elements with traditional styles. [Source: Junichiro Shiozaki, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 11, 2013]

“The theme of the new play is artists affected by politics, explored through the separation of Zeami and his son Motomasa, also a noh actor. The father-son tragedy, performed by Gensho Umewaka and Kurouemon Katayama, respectively, was enhanced by modern visual effects such as illumination and interesting sets. At one point Zeami says, “Politics has its own authorities, as does art.” His words are followed by a noh chant, saying: “The authorities of art can’t be affected, even by a shogun. I risk my life to pursue the way of art that has been handed down from the age of the Sun Goddess.”

“Unlike ordinary noh pieces, its lines are mostly written in modern Japanese and are thus more accessible to modern audiences. Umewaka and other performers’ elaborate chants and spoken passages keep noh’s inherent classical atmosphere intact throughout the portrayal of Zeami’s sense of failure and desire for creation for the future. “I wanted to make a world distinct from classical noh pieces,” Umehara said. “I used modern Japanese, as with my successful Super Kabuki pieces. No matter how much we value existing classical pieces, the art will dwindle if no new pieces are created. For its development, both new and classical pieces are necessary.”

“Compared to kabuki, there are far fewer noh spectators. If young noh actors actively make and perform new pieces, I believe they can attract new fans,” Umehara said. “Zeami was great because he created art that could entertain a wide range of people from his time, from shoguns to ordinary people. He was a genius by global standards. Japanese people should know more about him.”

Noh Today

Junichiro Shiozaki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Kanami was a noh actor and creator of many masterworks who founded the Kanze school of noh, which now has the largest number of members among the five noh schools. His son Zeami perfected noh under the patronage of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), the third shogun of the Muromachi period (1336-1573). [Source: Junichiro Shiozaki, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 11, 2013]

Kiyokazu Kanze, the current grand master of the Kanze school of noh, said: “Noh extends back nearly 700 years. This year I can celebrate as a member of the Kanze family. I’m very happy. I’m also very thankful to Kanami, Zeami and my other predecessors for the prosperity of noh today.” He said when he performs Zeami’s noh pieces, he becomes aware that noh creators of that time strove to depict humans through various themes and old stories. He also said noh consists of works of art that are filled with the gentle feelings of people from medieval times toward the departed souls of the dead.

Wakaba Kobayashi, chief editor of the Hana Moyo bimonthly magazine on noh and kyogen, said young noh performers have made efforts to attract new fans by hosting events and workshops after noting a decrease in the number of amateur noh students and the aging of noh spectators. “It’s only recently that all the noh circles began sharing the sense of crisis,” Kobayashi said.

Noh Outside Japan

Noh is alive outside of Japan. The Theater of Yigen in San Francisco has been staging Noh performances for more than 25 years. One American fan told the Daily Yomiuri she liked Noh because it “creates another kind of reality” and “pushes aside the veils that we have between time and space.”

Noh is invigorating itself in Japan by integrating influences from the outside. Kuniyoshi Ueda, a professor at Shizuoka University, has dedicated his life to producing Noh versions of Shakespeare plays in Japanese and English. Ueda pioneered the idea while on Fullbright scholarship at Harvard doing a Noh version of “Hamlet”, which has been staged over 100 times in a number of countries, including Australia, China, Sweden, Canada, Denmark and Vietnam. An Ueda-choreographed Noh version of Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House” was performed in Norway.

Image Sources: 1) Artelino Akitoya Terada 2) mask, British Museum, 3) robe, National Museum in Tokyo 4) Others Japan Arts Council

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014