KYOGEN, FARCES ABOUT HUMAN LIFE

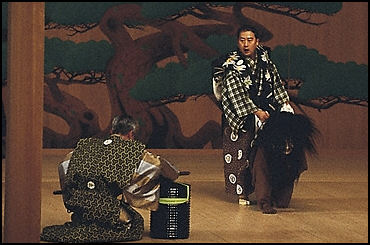

Kyogen “Kyogen” is a type of comic drama. Like Noh and kabuki it features only male actors but unlike noh and kabuki the performers don't wear elaborate costumes, make up or masks. Instead they wear kimonos and are accompanied by a chorus. In 2001, kyogen was designated by UNESCO, along with Noh, as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The short farces that are performed between the serious noh plays are called kyogen. Together, these two art forms are called nohgaku. Both forms have a lot in common. Both are performed on the same stage; in both forms all the actors are men, while they are both highly stylised in their styles of acting. However, in kyogen there is a tendency towards realism. Masks are only rarely used in kyogen; the costumes are simple, and music does not have an important role. If instruments are used, they are played softly so that they do not disturb the dialogue. While noh describes emperors, warrior lords, gods, and ghosts, kyogen concentrates on common people, such as mischievous servants and their gawky masters. Even monks and ghosts are seen from a comical viewpoint. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Kyogen developed from the humorous forms of “sarugaku”, which also produced Noh (See Noh), and has traditionally been performed in the intervals between Noh plays to offer little comic relief as a break from of the seriousness of a Noh drama. As time went in kyogen devolved more fully and was often shown as a complete performance between two noh dramas. Two schools of kyogen are still in existence.

Books: “A Guide to Kyogen” by Don Kenny (Hinoki Shoten, 1968). A variety of guidesand booklets are also available from the Japanese National Tourist Office (JNTO) and Tourist Information Centers (TIC).

Good Websites and Sources: Japan Arts Council on Noh and Kyogen www2.ntj.jac.go.jp ; Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Noh and Kyogen web-jpn.org/museum ; Noh and Kyogen Fact Sheet pdf file web-japan.org/factsheet ; Wikipedia article on Ragugo Wikipedia ; English Rakugo english-rakugo.com ; Japanese Theater columbia.edu ; National Theater of Japan and Japan Arts Council ntj.jac.go.jp ; Performing Arts Network of Japan performingarts.jp ; Traditional Performing Arts in Japan kanzaki.com ; Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum waseda.jp

Links in this Website: NOH THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KABUKI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUNRAKU, JAPANESE PUPPET THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KYOGEN, RAKUGO AND THEATER IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TAKARAZUKA, JAPANESE ALL-FEMALE THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS AND THE MODERN WORLD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FOLK MUSIC AND ENKA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DANCE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Kyogen History

“Kyogen”is thought to have its roots in entertainment brought to Japan from China in the 8th century or earlier. This entertainment evolved into “sarugaku”in the following centuries, and by the early 14th century there was a clear distinction among “sarugaku”troupesbetween the performers of serious plays and those of the humorous “kyogen”. As a component of “noh”, “kyogen”received the patronage of the military aristocracy up until the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868). Since then, “kyogen”has been kept alive by family groups, primarily from the Izumi and Okura schools. Today professional “kyogen”players perform both independently and as part of “noh”programs. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Noh and kyogen evolved from the same older theatrical forms. Sarugaku was one of the roots of the traditions of both of them. In the hands of Kan’amis and Zeamis in the early 14th century sarugaku was refined to become an extremely sophisticated form of serious drama, whereas kyogen continued to cultivate its lighter aspects. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Nohgaku, the combination of noh and kyogen, was the entertainment of the samurai class during the Muromachi period (1333–1568) and the Edo period (1603–1868). An exceptional actor, Hie Mangoro further developed kyogen and founded two kyogen schools or lineages in the Edo period, the Okura and the Sagi Schools. The third lineage, the Izumi School, was supported by the imperial court in Kyoto. **

As was the case with noh theater, kyogen also lost its traditional patronage when the old feudal world crumbled at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912). During the Edo period, the golden age of bunraku puppet plays and sensational kabuki, noh was still supported by the imperial court, while kyogen was regarded merely as an old-fashioned oddity. **

One of the three kyogen schools, the Sagi School, was closed down, but the other two lineages, the Okura and Izumi Schools, quietly continued to cultivate their art. There was a turn for the better after World War II when many forms of Japanese traditional arts were revived. Kyogen’s popularity has increased during recent decades. It is still performed as an interlude for noh, while, at the same time, it is also appreciated as an independent art form. **

Kyogen Roles

The word “kyogen”usually refers to the independent comic plays that are performed between two “noh”plays, but the term is also used for roles taken by “kyogen”players within “noh”plays (also called “aikyogen”). Among the “kyogen”roles found within “noh”plays, some are an integral part of the play itself, but it is more usual for the “kyogen”role to serve as a bridge between the first and second acts. In the latter case, the “kyogen”player is on stage alone and explains the story in colloquial language. This gives the “noh shite”time to change costumes, and, for uneducated feudal-era audiences, it made the play easier to understand. In the current “kyogen”repertoire there are about 260 independent plays. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In the most common classification system, these are divided into the following groups: “waki kyogen” (auspicious plays), “daimyo”(feudal lord) plays, Taro-kaja plays (Taro-kaja is the name of the servant who is the main character), “muko”(son-in-law) plays, “onna”(woman) plays, “oni”(devil) plays, “yamabushi”(mountain ascetic) plays, “shukke”(Buddhist priest) plays, “zato”(blind man) plays, “mai”(dance) plays, and “zatsu”(miscellaneous) plays.

“With the exception of the miscellaneous group, the largest category of “kyogen”is that of the Tarokaja plays. The Taro-kaja character is a kind of clever everyman, who, while he never escapes his destiny of being a servant, is able to make life a little more enjoyable by getting the best of his master. “Kyogen”costumes are much simpler than those used for “noh”and are based on the actual dress of medieval Japan. Most “kyogen”do not use masks, although there are about 50 plays where masks are used, usually for non-human characters such as animals, gods, and spirits. In contrast to the expressionless quality of “noh”characters, whether masked or not, “kyogen”performers depend on exuberant facial expressions

Kyogen Actors and Their Technique

As in noh, so too in kyogen the actors are named, not according to the character they play, but according to the importance of their role within the play. Thus the actor playing the leading role is, just as in noh, called shite, and the supporting role is ado (waki in noh). Other secondary actors are called by a generic name, koado. Kyogen’s stylised body language and its acting technique are, to a great extent, similar to those in noh, including the same basic posture, sliding, walking etc. (see The Acting Technique in the article on noh). [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

However, as mentioned above, the acting in kyogen is slightly more realistic than in noh. One drastic difference between these two “sister” styles is that exaggerated facial expression is used in kyogen, while in noh the face is kept completely expressionless. As kyogen mainly describes common people, its costuming is much more modest than noh’s. While in noh the actors’ socks are white, in kyogen they are yellowish. The music, including the chorus, both of which are of the utmost importance in noh, is only rarely included in kyogen plays. Thus the focus is on formally spoken dialogue. A speciality of kyogen’s language is the comic onomatopoeic words, which imitate the sounds created by various physical actions. **

Rare and archaic forms of kyogen also exist that are practised outside the two main kyogen schools. They are mainly performed in certain temples in Kyoto. One of them, Mibu kyogen, is believed to have evolved as early as the early 14th century. Mibu kyogen differs in its use of masks from mainstream kyogen, which is practised by the two kyogen schools mentioned above. Possibly because of the masks, the actors do not speak. Thus the drama is performed entirely as a mime, accompanied by a small group of musicians. As in kyogen generally, in this form, too, all the performers are men. Nowadays there are some 30 Mibu kyogen plays. In spite of their clear entertaining quality these folk plays clearly have a moral, didactic purpose, as they often recount the punishments of various, less good deeds. It is believed that these masked mimes stem from older, archaic, now extinct, Buddhist mask plays. **

Kyogen Plays

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Today there are some 260 plays in the kyogen repertoire, all of them anonymous. These short plays (of about 30 minutes) may be classified according to their subject matter. The classification differs slightly in the two existing kyogen schools, those of the Okura and Izumi Schools. Roughly speaking, however, they deal with the following main subjects: plays about various gods, plays about feudal lords, plays about their servants, plays about family relationships, plays about Buddhist priests, plays about blind men etc. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Probably the most popular character in the whole kyogen repertoire is a wily servant called Tarokaja (synopsis of the play Tied to a Pole). He and, occasionally, his fellow servant Jirokaja do all kinds of mischief, which leads to conflicts with his master. Both servants and master are mercilessly treated as comic characters. Thus it is not always clear who, in fact, is the clever one and who is the fool. **

In addition to classifying the farces according to the main character of the play, another way to classify them is based on their endings. A play may be “resolved” or “unresolved”, according to whether the audience is shown what finally happens to, for example, the mischievous servant at the end of the play. These two basic categories are further subdivided into subcategories, such as plays ending with laughter, flute music etc. **

Famous Kyogen Plays

Famous kyogen plays include “Bakuchi Juo” ("The Gambler"), about the Master of Hell playing a dice game with the audience; “Niwatori Muko” ("The Rooster Son-in-Law"), about a mischievous teacher who convincer his student to act like a rooster when he visits his wife's parents for the first time.

A popular theme in other plays is the relationship between master and servant. “Kuriyaki” ("Roasting Chestnuts") is about a servant eating all of his master's chestnuts and the excuse he provides for doing so. “Kuji Zainin” ("Sinner by Lottery") is about a conflict between a master and servant during a festival in Kyoto.

In “Two-in-One Hakama” two men show up as guests to a formal party and realize they only have one formal hakama between them. At first they take turns wearing the hakama and go into the house separately. When they are requested to go into together they tear the hakam un half, each wearing half on the front part of their legs. Much of the comedy revolves around their efforts to avoid exposing their backsides.

In “The Delicious Poison” a master leaves his treasured supply of molasses in the care of two servants. Worried the servants might try to consume the molasses the master tells them it is poison so powerful that simply inhaling the fumes blown by a breeze is enough to kill. After the master leaves, a strong wind blows up and the servants breath in the fumes and nothing happens. They then decide to try the molasses and find it so delicious they eat the entire supply and in the process of their feat destroy some other valuable possessions of the master, When the master returns the servants tell him they accidently broke the possessions and felt so bad they tried to commit suicide by consuming the molasses.

Kyogen Performances

Unlike highly symbolic and spiritual Noh, kyogen draws its inspiration from the real world and features actors who speak in colloquial Japanese. Many plays are satires of weak samurai, dishonest priests or unfulfilled women. Taro Kaha, a servant, is a stock player who appears in many kyogen plays. Sometimes clever, sometimes foolish, he has a knack for getting in trouble.

Kyogen focuses on the script with asides to the audience and bantering dialogue and comedic repetition. The language is much less elevated than that of Noh and is easier for ordinary Japanese to understand, The action is more energetic and realistic as opposed to the slow, stylized movements of Noh.

Kyogen has experienced a revival partly through the energy of Nomura Mansai, a young fresh-faced performer who has livened up the show with light effects and electronic displays that explain what is going on on stage. Normura is the eldest son of Mansaku Monura who credited with introducing kyogen to overseas audiences.

Kyogen has also been given a boost by the handsome kyogen actor Motoya Izumi, who had the lead roll in one of the most popular television dramas of 2001.

Rakugo

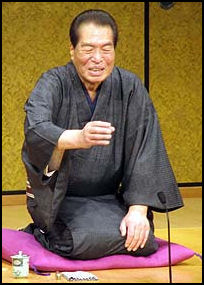

“Rakugo” (literally meaning "dropped word" or "punchline") is a form of comic monologue that usually features a kneeling performer dressed in kimono whose only props are a towel, a fan and the cushion he sits on. Their act include female impersonations, mimicry of animals and natural sounds, and the telling of stories with wild gestures and contorted facial expressions.

Some rakugo comedians are known for their flamboyant storytelling styles, with humorous gesticulations and facial expressions. The famous “rakuoka” Katsura Shjaku once said his aim was to make audiences laugh without uttering a single word.

Rakugo dates back to the 16th century and is believed to have evolved from court jest-like entertainment for daimyos (feudal lords). The art form came into its own in the Edo period as a form of entertainment for the urban elite in Tokyo. In 1791, the first theater devoted to rakugo was established in Tokyo. By the mid-19th century there were 200 such halls in Tokyo and scores more in other Japanese cities. Today, there are only handful of these halls but rakugo is often shown on television.

Famous rakuoka include Kanmi Fujiyama, who played the lead role in 10,288 performances by the comedy company Sochiki Shokigeki from November 1966 to June 1983; Katsura Shijaku, who is credited with revitalizing rakugo in the 1970s by making the genre popular among non-Japanese by performing in English and lighting up audiences with his wild expressions and body movements. He died from a heart attack in 2000 after trying to hang himself.

Osaka-based Katsura Kaishi performed in English during an 11-city, six-month tour of the United States. He performed in Los Angeles and Washington and on Broadway and traveled with his family in a mobile home. His English-repertoire includes the piece “Time Noodles”. During his shows he didn’t get much response for his classic rakugo pieces but drew reasonably big laughs for his free talks and informal pieces about an American perplexed by Japanese customs, at one point getting the audience to imitate the Japanese way of slurping noodles.

Rakugo storyteller Katsura Koharudanji has performed at Carnegie Hall and the United Nations headquarters in New York.

Rakugo Performance and Animal Mimicry

Describing a rakugo television show William Penn wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Rakugo artists sit on a bare stage while the host doles out joke assignment or cheap props with which they are to create some humorous scenario...Each man tries to quickly turn these raw materials into a witty joke or anecdote. The host judges whether they are successful and rewards the winner with another zabuton cushion...The goal is to be sitting on as many zabuton cushions as possible by the end of the show. If a comedian comes up with a sick, overly silly or predictable response, or if someone in the audience beats him to he punch line, he loses one of his coveted cushions.” Rakuoka often impersonate women but it is considered bad taste for women to impersonate men.

A typical rakugo joke goes like this: a group of boys are sitting around talking about things that scare them. The usual things, snakes, spiders are mentioned. One boy says he’s afraid of “manju” (sweet bean paste buns) then says he needs to take a nap. While he’s sleeping the other boys figure they will play a joke on him and place some manju next to his head. When he wakes up the boy first acts afraid and then laughs and eats the bun, saying he actually loves the buns. When the boys ask what he is really afraid the boy says, “Right about now I’m afraid of a nice cup of tea.” [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

Henshu Techo wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “There is a rakugo comic story titled "Akubi Shinan" (yawn mentor) in which a man trains under a master yawnist to learn how to yawn properly. As the great haiku master advises, I've gradually come to see the study of yawning as a worthwhile pursuit, even paying a monthly fee for lessons.[Source: Henshu Techo, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 26 2012]

“Mone-mane” is the art of making animal sounds, and the masters of this are the Okada family — Edo-ya Neko-Hachi (Cat Eight of the House of Edo), his son Ko-Neko (Little Cat) and daughter Maneki Neko (Beckoning Cat) — who do a vaudeville-style routine that include dog howls, pigeon coos, roster crows and nightingale songs. Summing up his profession, Edo-ya Neko-Hachi told the New York Times, "I make people laugh. I make them cry, and make them feel moved. And I do animal sounds."

Rakugo Master Tatekawa Danshi

Popular Rakugo comic storyteller Tatekawa Danshi, famous for his free-spirited style, died of larynx cancer in a Tokyo hospital at the age 75 in November 2011. A former member of the House of Councillors, Danshi was a gifted storyteller with many fans, though he sometimes caused controversy with his caustic tongue and defiant statements. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 25 2011]

Danshi was born Katsuyoshi Matsuoka in Tokyo in 1936. He became an apprentice to Yanagiya Kosan V in 1952 and was promoted to shinuchi, the top rakugo rank, in 1963. At that time, he received the name Tatekawa Danshi V. His popularity particularly grew while he was futatsume, the second-highest rank, and performed under the name Yanagiya Koen with his forceful, cutting words.

Danshi was hailed as one of the "Yose Shitenno," or big four of vaudeville theater, together with popular rakugoka including the late Sanyutei Enraku V. Danshi was the first emcee of the NTV network's long-running comedy program "Shoten." The program began in 1966, and he became popular on TV, radio and film.

In 1971, Danshi was elected to the upper house as an independent candidate in the then nationwide constituency. After joining the then ruling Liberal Democratic Party, he served as parliamentary vice minister at the Okinawa Development Agency for just 36 days from December 1975 to January 1976. Danshi was forced to resign because he appeared at a press conference with a hangover and then did not attend a Diet committee session where he would have had an opportunity to explain himself, saying he had to go to the theater to perform.

Danshi also clashed with the Tokyo-based Rakugo Kyokai (association of rakugo comic storytellers), headed by his master Kosan, over the promotion of an apprentice. He withdrew from the organization with his apprentices in 1983.Subsequently, Danshi founded the Tatekawa school of rakugo, where he raised such popular young storytellers as Tatekawa Shinosuke and Tatekawa Danshun. Danshi accepted people from outside the rakugo world, including comedian Beat Takeshi and TV and radio scriptwriter Fumio Takada.

In 1997, Danshi announced he was suffering from esophageal cancer, but he returned to the stage after surgery. In August 2009, Danshi announced he would "take a rest" due to his ailing health, but he started performing again in April 2010. According to Danshi's family members his larynx cancer was discovered to have returned in November 2010. His son, Shintaro Matsuoka, said Danshi rejected medical advice to have his vocal chords removed, due to his pride as a rakugo storyteller and in being Tatekawa Danshi. As a result, only the surface of his cancer was removed. Danshi's last stage performance was in March 2011 in Kawasaki.

At the end of March, Danshi underwent an operation on his trachea. "Can I talk? Can I let out my voice?" These were Danshi's first words after the operation, communicated to his family through writing. However, he had lost his voice, which his family said was a profound shock to him.

Other Classical Forms of Japanese Entertainment

Other forms of classical entertainment include storytelling, acrobatics, juggling, comical monologues and “manzai” (comic dialogues). There are an estimated 800 vaudeville performers in Japan, with about half of them based in Tokyo. Pantomime actors wear wooden masks, following a 700 year-old tradition. “Kodan” is a style of storytelling in which the storyteller hits a small table with fan when making a point while telling the story.

“kamishibai” (literally “paper theater”) is an art form in which a performer tells a children’s story while showing pictures that depict each scene.

The staple of television variety shows are comedy two-person stand-up teams known as manzai. Most teams consist of a “”boke” — a fool who makes some sort of silly, stupid statement and the “tsukkomo”, the straight man who corrects him. The timing of the tsukkomi’s education is regarded as critical to the success of a joke or routine,

Shizuoka (100 miles from Tokyo) hosts the Theater Olympics, which draws around 40 productions form 20 countries annually.

Okinawa has its own form of national theater — “kumidori” — a noh-like all-male dance drama performed without masks. Regarded as more slow-moving than noh or kabuki, it revolves around stories of unrequited love and Confucian values and is performed to the rhythm of hyoshigi clappers and music from a three-stringed samisen, a koto, bamboo flutes, kokyu fiddle and odaika and shimedaiko drums, Many pieces are written by Chokum Tamagusuky (1684-1734), an official in the Ryukyu kingdom who wrote the pieces with the purpose of entertain Chinese envoys to the islands.

Japanese Wows Chinese in Beijing Opera Competition

Takanori Kato wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Yuta Ishiyama, the sole foreign-professional Beijing Opera performer, has received high praise from Chinese people for tackling one of the genre’s best-known roles--Sun Wukong--and earning a place among the top 15 contestants in a competition broadcast on television. The airing of the competition on China Central Television had a high viewership. Participants were judged on how skillfully they performed the role of the legendary monkey king, known in Japan as Son Goku. Ishiyama, 38, is based in Beijing. Amid tensions between Japan and China over the Senkaku Islands, he said, “I’ll be happy if [my achievement] eases anti-Japan sentiment [in China], even if it’s just a little.” [Source: Takanori Kato, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 9, 2013 :]

“About 300 contestants entered the TV competition, including Beijing Opera actors, people from the local circus and martial arts practitioners. Behind-the-scenes footage of the selection process--screening of documents followed by individual and group auditions during a training camp--was aired recently. On the episode that aired June 14, Ishiyama was featured among the top 15 finalists. Though he did not advance to the round of seven on June 16, the show’s host praised him, saying, “What you’ve done to make Beijing Opera popular in Japan is a tremendous achievement.” :\

After last summer’s turbulent anti-Japan rallies, countless friendship projects between Japan and China were canceled, depriving Ishiyama of his usual opportunities to perform. Consequently, he worried that he might be disqualified in the document screening stage of the competition. But after the show’s national broadcast, Ishiyama was repeatedly approached in Beijing subway stations by Chinese fans who were eager to praise him for his performance. :\

Ishiyama grew up in Tokyo’s Asakusa district. When he was a primary school student, he watched a performance of “Journey to the West” (known as “Saiyuki” in Japan) by a Beijing Opera troupe on TV, and the character of Sun Wukong caught his eye. After graduating from high school in 1993, Ishiyama enrolled at a high school attached to the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts in Beijing. In 2001, he graduated from the academy and joined the China National Peking Opera Company, becoming the troupe’s first-ever foreign member. Since then, he has performed both in Japan and China. In 2010, he garnered special attention for a joint performance featuring performers of classical Japanese dance. :\

Modern Theater in Japan

Actors who perform on the stage get paid about one tenth the money per show as they would get for one episode of a television drama. They don't get paid anything for rehearsals.

Dan Grunebaum wrote in the New York Times,”Contemporary Japanese theater remains by and large terra incognita. Abroad, Japanese theater directors are mainly known in the form of Amon Miyamoto’s Broadway hits and Yukio Ninagawa’s kabuki Shakespeare productions. Performances of new Japanese theater are rare, leaving a gaping hole in the world’s understanding of the country’s performing arts scene. [Source: Dan Grunebaum, New York Times, May 26, 2010]

Kara Juro is one of Japan’s most famous modernist playwrights, He started a theater troupe on the 1960s called the Jokyo Gekijo that is still active today and performs in a blood red tent in Shinjuku, Tokyo. He is famous for his temper and barroom brawls. He led one celebrated battle between two theater troupes that had to be broken up by police.

Japan doesn’t have a Broadway or West End. There are no long-running play per say. There are instead numerous amateur groups. Plays stay alive by being staged numerous time by these groups.

The playwright Shoji Kokami told the Times of London, “Because we don’t have a long-run system. It’s quite hard to keep on being an actor, so a lot o people come to Tokyo looking for an opportunity, fail and go back to their province. But they still love acting, so they get into amateur theater companies.”

Japanese directors have a reputation for being very harsh, Kokami told the Times of London about one Japanese actor who suddenly burst into tears when working under a British director. The director asked him why. The actor said, “I’ve never been treated in such a gentle way by a director” and told the director about how cruel Japanese directors are.

Gamarjobat is a comedy mine duo known for their punk outfits and silly routines. Made of two Japanese guys who go by the names Hiro-Pom and Ketch!, they has wowed audiences around the world and won awards at the prestigious Edinburgh Fringe Festival. “Gamarbjobat” is “hello” in Georgian. In their acts, which is performed to rock or hip hop music, they do things like chase each other on imaginary escalator and elevators.

Popular Plays in Japan

Amon Miyamoto is a leader in American theater. He brought “Pacific Overtures”, Steven Sondheim musical set in Japan and writeen with a Japanese perspective, to Broadway, and transformed “The Nutcracker” into an urban Japanese musical. In 2005, “Pacific Overtures” received four 2005 Tony Award nominations,

The Tokyo Shock Boys have made audiences around the world squirm in the seats with their antics: drinking engine oil, splitting cactus with their butts, eating live worms, exploding firecrackers in their mouths and sucking up milk in their nose and squirting it out their eyes. The "Boys" range in age from their early thirties to late forties.

Manga such as “Tenisu no Oji-sama” (“Princes of Tennis”) and Japanese video games “Sakura Taisen”(“Sakura Wars”) have been into theater productions.

“Trance”, by Shoji Kokami, is a popular play about three old school chums that run into each other by chance, It has been staged hundreds of times by local amateur groups.

Shu Matsui

Translations into English and other languages of recent works by the playwright and director Shu Matsui has given him some exposure to a world audience. Festival/Tokyo, Japan’s leading performing arts showcase, regards Mr. Matsui as one of the country’s most important young directors, and translated his disturbing, surrealistic “Ano Hito no Sekai” (That Man’s World). [Source: Dan Grunebaum, New York Times, May 26, 2010]

Dan Grunebaum wrote in the New York Times, “The son of a lawyer and radio announcer, Mr. Matsui spent an unremarkable childhood and only ended up in theater when he followed a girl he had a crush on into his high school drama club. There he was bitten by the theater bug, and spent his 20s as a professional actor and odd-job worker before his 2004 breakout “Tsuka” (Passage) was given the New Face Award by the Japan Playwrights Association...Mr. Matsui himself labored for a while on a conveyor belt as a struggling actor. Reflecting his experience, the workers of “Hakobune” are the passive Japanese freeta — those unable to land full-time jobs — of the moment rather than the Marxist rebels of “Kanikosen.”

“I’d been an actor for 13 years, but didn’t start to think about writing my own plays until I was past 30,” Mr. Matsui, who was 37 in 2010, told the New York Times. “I wanted to create a world that I found compelling, and to see if it compelled others. I wondered if others shared my anxieties. It surprised me when people related to my work, especially since the first one about a family that is taken over by outsiders was pretty disturbing.”

Bestiality and rape appear in Mr. Matsui’s work, but the violence serves a cautionary purpose he told the New York Times. He cites the intense interest among his generation in the “otaku murderer,” Tsutomu Miyazaki, who between 1988 and 1989 mutilated and killed four young girls, molesting and cannibalizing their corpses. “He said before his execution that he was told to do so by someone in his head, and that it was not his fault,” Mr. Matsui recalled. “Ever since then I’ve been fascinated by his comments. His thinking is different from thinking up until now. He has no interior life, no feelings. We want him to express remorse and show his feelings — we think this is part of being human — but maybe that’s not the case, and maybe we are all heading in his direction.”

That Man’s World, Zombies and Ark

Describing “Ano Hito no Sekai” (That Man’s World), Dan Grunebaum wrote in New York Times: “Via his Sample company’s eye-catching, multilevel staging, the play follows the story of a directionless loner in rural Japan who searches for meaning in anarchic, bestial ceremonies. But the larger theme is the intolerance lurking behind the polite facade of Japanese society. “The story is about people whose prejudices prevent them from interacting,” Matsui said “I wanted foreigners to see the play because it deals with bigotry. Living in homogeneous Japan there aren’t many chances to confront one’s prejudices, so they remain hidden.”

Key to “Ano Hito no Sekai” was the way that the characters acted mechanically and didn’t even attempt to scale walls of mutual noncomprehension. This grew out of Mr. Matsui’s view of Japan as a zombie nation.” Explaining why he liked the image of a zombie, Matsui told the New York Times: “Zombies represent the future of mankind: they have no soul, no interior, no emotions. They wander about with no purpose, they respond to stimuli — for example if there is an escalator at a shopping center they’ll go up and down — but that’s all they do. Their form to me somehow represents what humans are heading toward.”

His most recent work “Hakobune” (“Ark”) is based on Takiji Kobayashi’s landmark Japanese Marxist novel “Kanikosen” (“The Crab Ship”), about exploited crab cannery workers. The 1929 book has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity in Japan amid the financial crisis and hardships facing the nation’s young. The play depicts dead-end, part-time workers performing meaningless tasks at an anonymous factory. They suffer under the hand of an overseer, but midway roles are suddenly reversed and he becomes an underling. Relentlessly cheery J-pop music and ubiquitous cellphones inject notes of everyday Japanese reality into an absurdist plot in which even death is a matter of little import.

Hideki Noda's 'The Bee'

Hideki Noda is a Japanese actor, stage director and playwright. Born in 1955, he began acting in high school and performed central roles in his own theater company Yume no Yuminsha (dreaming bohemian)--which he founded as a student at the University of Tokyo. Following the group's breakup in 1992 and his study in Britain, Noda started a new company, Noda Map, in 1993. He became more involved in writing and directing drama, including the highly acclaimed Kill, Pandora's Bell and Red Demon. [Source: Hiroko Oikawa, Daily Yomiuri, January 20, 2012]

Noda'splay “The Bee” went on a world tour in English in 2011. After stunning New York audiences in January 2012 it' went to London, Hong Kong and Tokyo, after which the Japanese version will be performed across the country from April to June. "The Bee is a helpless tragedy with no recourse. Tragedy usually has some quiet moments along the way, but this story descends head-on, which resembles the situation following Sept. 11," Noda said in an interview with the Yomiuri Shimbun.

Hiroko Oikawa wrote in Daily Yomiuri, Based on the short story Mushiriai by popular author Yasutaka Tsutsui, the drama portrays the degeneration of a typical businessman named Ido into a ruthless savage after his wife and young child are taken hostage by an escaped convict. Ido decides to take revenge by holding the fugitive's wife and child captive. Noda said he decided to use the story in a workshop he was asked to do for young actors in London in 2003 after the September 11 attack in New York and the Iraq war.

Following a few more workshops with veteran actors, The Bee, cowritten by Noda and Colin Teevan, opened at London's Soho Theatre in 2006. Ido was played by actress Kathryn Hunter--winner of the 1991 Laurence Oliver Award for Best Actress--while a number of other roles were performed by three actors, including Noda, who played the convict Ogoro's wife. The show played to full houses in London, enthralling audiences and earning rave reviews. "The story probably reminded the audience of the impact of the Iraq war, which many of them did not support. From the 2003 workshop on, there was a sensitive response, although the story does not mention the war," Noda said. "It's a story about revenge between families, but it conveys very well how foolish revenge is."

Ido suddenly turns violent in the play, unable to bear his misfortune and angered by the insensitivity of the police and media. He rapes Ogoro's wife, and cuts off his son's and then the wife's fingers one after another. "I was aware the actresses were not very happy about [the rape scenes]. Then I thought about Hunter playing the man's role, which would make it seem different," Noda said. Hunter--who had joined the project from the fourth workshop--agreed on condition that Noda play Ogoro's wife. "That's how I became involved in this production as an actor. An actress raping a male actor has created more impact than her raping an actress," Noda said, adding that the audience accepted the scenes well.

Noda says the original story's latter half, with its repetition of everyday life, was difficult to stage. "The culprit and victims are together, becoming numb to the escalating violence in the daily routine of waking, eating, cutting off the kid's fingers, sending them to his father, having sex and sleeping," Noda explains. "Ido justifies cutting off the child's fingers and sending them to Ogoro through sex. It's like a soldier in combat justifying his violence through sex and drugs."

Interestingly, there is no bee in the original story. So why is the play called The Bee?"We thought it would be interesting if Ido was afraid of a bee. His violence escalates after he kills a bee and feels in control of everything," Noda explained. "In the last scene, he is no longer affected by imaginary bees after his senses have become numb."

Korean Musicals Popular in Japan

Chung Ah-young wrote in the Korea Times, “Japanese first lady Akie Abe, known to be a fan of Korean soap operas, was criticized recently after posting a message that she had watched “Caffeine,” a Korean musical, on her Facebook on May 9, along with a photo of herself in front of a poster promoting the show. Consequently, the wife of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe drew numerous critical responses from the Japanese public who thought it is “careless” considering the sour relations between Seoul and Tokyo. This happening shows how Korean musicals remain popular in Japan despite the recent diplomatic rows between the two countries. “Caffeine,” which hit the stage in Tokyo’s trendy Roppongi district, is a Korean musical recently gaining popularity in Japan with a cast of Korean actors and singers. [Source: Chung Ah-young, Korea Times, May 31, 2013 ==]

“It is about a couple who accidentally fall in love after meeting at a coffee shop. When the musical raised its curtain on April 25 in Japan at the opening day of Amuse Musical Theater, a special venue solely dedicated to the Korean musicals, the first of its kind, some 900 seats were packed. The theater is run by Amuse Inc., one of the major Japanese entertainment companies in cooperation with Korean counterpart CJ E&M. ==

“The popularity of Korean musicals began burgeoning in Japan around 2010 when hallyu stars were frequently appearing in the shows, according to the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA). “Korean musicals are seeing a breakthrough in the Japanese theater market which is recently declining compared to other music industries,” KOCCA said in its industrial report. The scale of the Japanese market for musical theater is double the size of Korea’s, which is worth some 300 billion won. Also more than 90 percent of the Japanese musical industry is dominated by foreign licensed musicals rather than its own domestic productions. ==

“Gwanghwamun Sonata,” which hit Japan last year, starred K-pop singers Yunho from TVXQ, G.O. and Seungho from MBLAQ, Yoseob from B2ST and Choi Min-hwan from F.T. Island who have tens of thousands of Japanese fans. The musical is based on hit songs composed by the late legendary Korean composer Lee Yong-hun. The latest hit musicals are “Summer Snow” starring Sungmin from Super Junior and “Jack the Ripper” starring Changmin from 2AM. “Jack the Ripper” set the highest record of 81.5 percent seat occupation among large-scale musicals staged in Japan. It is originally a Czech musical but was adapted into a Korean format which slightly modified its characters and choreography. Japan chose to present the Korean version instead of the original work. The Korean production received a standing ovation at the Aoyama Theater in Tokyo in Japan last year. ==

““Jack the Ripper” is seen as one of the most successful models in Japan presented by M Musical Company which used market research into audience tastes for a couple of years. The company also paved the way for exporting the license of the Korean production of “Singing in the Rain” to Japan for the first time in 2007. Based on a Japanese soap opera starring Domoto Tsuyoshi and Hirosue Ryoko which was broadcast by TBS in 2000, “Summer Snow” has been adapted into a musical by Eunhasu Entertainment. The star-studded musical is attracting more Japanese fans as Sungmin and Sungjae from Supernova, Seunghyun from F.T. Island, Huh Youngsaeng from SS501, and Kevin and Suhyun from U-Kiss appear in the show. ==

“The musical portrays the story of a youth growing up along with a love story between a young man who matures too quickly, and a young woman suffering from an ailment. Sungmin, Sungjae and Seunghyun play the main character Natsuo while other roles are performed by Heo, Kevin and Soo. The musical was produced after two years of preparation and is intended to be taken to other Asian countries by including Japanese content and creating a new production and distribution format. After the successful opening performance in Osaka in April, it will play in Tokyo from May 31 to June 15. ==

Image Sources: 1) 2) 3) Japan Arts Council 4) 6) 7) JNTO, 5) Japan Zone

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014