KABUKI

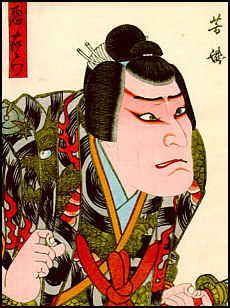

Kabuki actor by

Yoshitaki Utawgawa Kabuki is a popular form of Japanese musical drama characterized by elaborate costuming and make-up and stylized dancing, music and acting. Both male and female acting roles are performed by men. Kabuki has been influenced by Noh theater and bunraku puppet plays. Unlike Noh theater, which has traditionally been a classical art form enjoyed by the upper classes, kabuki has been a popular form of theater enjoyed by the masses. In November 2005, kabuki was designated by UNESCO as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity,

Although non-Japanese, and even many Japanese, can't understand what the actors say, kabuki's wild costumes, expressive make-up, slapstick action and dance can hold the interest of most Westerners for about a half an hour (but unfortunately most Kabuki plays are four or five hours long, including the long pauses which are supposed to give observers a chance to think).

Kabuki has been described as "actor-centered, sensory theater" in which beauty is the aim not reality or consistency as is the case with "intellectually-centered" Western theater. In some ways kabuki audiences are like people who go to watch a first-rate matador at a bull fight. They already know the story and the ending. What they come to see is how beautifully the actors perform their roles, which are often heavily stereotyped and one dimensional. Playwrights are given only secondary importance. The emphasis of kabuki is on creating a beautiful. actor-based spectacle with larger than life gestures, musical enhancement provided by the accompanying orchestra and highly stylized entrances and exits. Kabuki has been compared to a living woodblock print, in that each moment of a kabuki play, if frozen, would capture a scene of remarkable beauty.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: No other traditional form of theater in Asia has evolved into such a grandiose stage spectacle as the kabuki theater, which is four centuries old. As its name, kabuki (song-dance-acting), indicates, it combines various genres of dance and music while it is characterised, at the same time, by its highly exaggerated, mimetic acting style. Kabuki’s origins in sensational street performances and its later developments in the teahouse theaters of the notorious red light districts of the growing cities of the Edo period can still be traced in kabuki’s eroticism and its rich repertoire. Kabuki also adopted themes from its sister form, bunraku puppetry, as well as from the much older noh theater. During the golden age of kabuki, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the teahouse theaters grew in size, and complicated stage machinery with its revolving stage, lifts and several curtains was invented. Thus kabuki offers a colourful panorama of stage tricks, changing forms of scenery, and theatrical magic, rare in most forms of Asian theater, which mainly focus on the actor’s art. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki]

Book: “Kabuki Today: The Art and Tradition” (Kodansha International, 2000); “Kabuki Handbook” by Aubrey and Giovanna Halford (Tuttle, 1979); A variety of guides and booklets are also available from the Japanese National Tourist Office (JNTO) and Tourist Information Centers (TIC).

Good Websites and Sources: Japan Arts Council www2.ntj.jac.go.jp ;Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Kabuki History kabuki21.com/histoire ; Kabuki Butai library.thinkquest.org ; Kabuki Make Up creative-arts.net/kabuki ; Kabuki Costumes and Make Up comm.unt.edu ; Kabuki for Everyone park.org/Japan/Kabuki ; Kabuki 21 kabuki21.com

Kabuki in Kyoto and Osaka: Minami-za Kabuki Theater (near the Kamo river) is the oldest Kabuki theater in Japan. Near the spot where the theater now stands, a Shinto priestess and her troupe performed the first Kabuki in 1603 to raise money for a shrine. Most performances are held during the Kaomise festival from the end of November to late December. Welcome to Kyoto Kyoto Prefecture site . In Osaka, Kabuki is performed at the Shin Kabukiza Theater. The No Kaikan. Sochiku-za Theater sometimes hosts kabuki performances. Kabuki and Noh in Tokyo are staged throughout most of the year at the National Theater and the 1,900-seat Kabukiza Theater in Ginza. These days theaters with kabuki and noh performances provide synopses written in English and earphone guides, with detailed English translations that coincide with the action, to help foreign observers. Kabuki-za kabuki Website shochiku.co.jp . National Theater of Japan (near the Imperial Palace, ) is one of the premier Kabuki and Noh theaters in Japan.

Website: National Theater of Japan site ntj.jac.go.jp

Links in this Website: NOH THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KABUKI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUNRAKU, JAPANESE PUPPET THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KYOGEN, RAKUGO AND THEATER IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TAKARAZUKA, JAPANESE ALL-FEMALE THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS AND THE MODERN WORLD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FOLK MUSIC AND ENKA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DANCE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Meaning of Kabuki

Kabuki means "song and dance technique" and is derived from a word meaning “tilted,” “slanted,” “offbeat,” “outrageous” or eccentric. There are two ways to interpret sources of the word “Kabuki”. First, the simpler one says, that this name comes from three words: “ka” which means singing, “bu” = dancing, “ki” =acting. It’s supposed to be truth, because Kabuki as a performance contains all of this elements. But this word is also believed to derive from the verb “kabuku”, meaning “to lean” or “to be out of the ordinary”. So Kabuki can be in the other way interpreted to mean “avant-garde” or “bizarre” theatre. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The justification to this second theory we can find in the book of Masakatsa Gunji — “Kabuki”. Due to the author’s words, there exist one unique aesthetic concept of Kabuki theatre, which is giving it consistency — the concept of yatsusi. The author gives a definition: “Yatsushi is basically an attempt to modernize everything, to transfer it into terms of contemporary society, to parody the old by recreating it in terms of the present and familiar”. To follow this rule, we can say that Kabuki is no more that the yatsusi of Noh and Kyogen ( in the same way “haiku” — the short lyric forms — are yatsusi of the classical waka verse poem.)

The oldest Japanese form of classical theatre is Noh. First printed texts date from about 1600 year, but the language in which they were written came from XIV century and it’s already mature, that is why there are supposed to be much older. Kabuki and Burnaku are younger art-forms, established by the time the centre of power had shifted to the east with the setting up of the Togunawa Shogunate (lasted until the restoration in 1868) at Edo (modern Tokyo), at the beginning of XVII century. They reached their highest point of development in the 2nd half of the century, and remained more or less static for some time. Since 1945 the many small Kabuki troupes which used to tour the countryside have been disbanded and performances have been given only in larger city.

Early History of Kabuki

Kabuki performers during the earliest years of the genre were primarily women. The first formally recognized kabuki show was performed in Kyoto at in 1603 by a Shinto priestess named Izumo no Okuni and her troupe of female dancers to raise money for Izumo Taisha shrine. Though based on Buddhist prayer dances, early shows were generally romantic tales intended as popular entertainment. Like Noh, kabuki has its roots in drama, music and dance that can be traced back to the eight century.

Early Kabuki, known as “kabuki odori” (which roughly means “avant garde dance") were primarily dances, often known for their lewdness and vulgarity. Although women helped popularize the art they were banned from Kabuki in 1629 by the The Tokugawa shogunate because many of the lead actresses were prostitutes and producers were concerned about fights breaking out between men trying to win the attention of the actresses. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: If kabuki itself can be defined as “colourful”, the same, indeed, also applies to its history! The long process of the evolution of kabuki started on a river bank in Kyoto in 1603, when a group of female entertainers performed their variety show, led by a shrine maiden, Okuni. In fact, the institute of “shrine maidens” had, by then, partly degenerated into prostitution. The dances may have been based on earlier Buddhist shrine dances, while the music of this earliest variant of kabuki, actually onna kabuki (women’s kabuki), was derived from noh theater. A new instrument, the three-stringed shamisen, the fashionable instrument of the period, however, gave it a new kind of attraction. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The short dance numbers and skits, performed by Okuni’s troupe, created a sensation because of their eroticism, their exotic costuming, which partly imitated the costumes of the Portuguese missionaries, and because of their cross-dressing scenes. The latter were, of course, not a complete novelty. In the much older noh theater, for example, masked men played the female roles. What was new, however, was that women now appeared in male roles. **

Kabuki was inspired by the activities of Kabukimono, urban youths who were the punks of their day. They traveled in armed groups, thumbing their nose at middle class values and harassed anyone who got in their way. “Wakashu” (young men's Kabuki) then became popular after women were banned from the stage, but in 1652 it was also banned because of the adverse effect on public morals of the adolescent male actors.

Women and Young Men Banned from Kabuki

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: "This first variant of kabuki was obviously connected to prostitution. So it was no wonder that the teahouse theaters of the red light districts soon adopted it too. Thus they could provide their customers with a new kind of entertainment while, at the same time, on the stage, they were able to advertise their merchandise, the girls. Because of the great popularity of “women’s kabuki” and the uproar it created among male audiences, officials banned the onna kabuki in 1629. This led to the next variant of kabuki, that of wakashu kabuki or “young men’s kabuki”. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The teahouse brothels also offered the services of young men, rather popular in the bisexual atmosphere of the “pleasure quarters” and their particular life style called ukioyo or the “floating world”. When girls were banned from the stage, boy actors replaced them. Boys with “sexy” forelocks (usually shaved at the boys’ coming-of-age ceremony) in particular gained popularity in the female roles, and they immediately got ardent male admirers. Once again, in 1652, officials had an excuse for censorship and they banned this form of kabuki, thus putting an end to the short period of “young men’s kabuki”. **

Adult men, however, were not prohibited from performing on the stage, which led to a new and final variant of kabuki. It was yaro kabuki or the “male’s kabuki”, in which all roles, even the female ones, were played by grown-up male actors. Kabuki distanced itself from prostitution and began to attract serious dramatists. Talented actors also contributed to its development by creating new types of role, such as the exaggerated onnagata or the female impersonator, wagoto, or the elegant male lead, and later aragoto, the powerful male lead. Each of them inspired new types of dramas. **

With both women and boys banned, “kabuki” became a theater of mature male performers, although before “yaro” (men’s) “kabuki” was permitted to continue performing, the government required that the actors avoid sensual displays and follow the more realistic conventions of the “kyogen” theater.

The law that stipulated that only older men could play the leading roles gradually led to the development of kabuki as a serious dramatic form with stories based on history, legend and contemporary life. Since the 1700s all female roles have been played by male actors. “Onnagata” (female impersonator) roles became increasingly sophisticated, and Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660-1704) pioneered the strong, masculine “aragoto” (rough business) acting style in Edo (now Tokyo), “Kabuki” is one of the four forms of Japanese classical theater, the others being “noh”, “kyogen”, and the “bunraku” puppet theater.

Later History of Kabuki

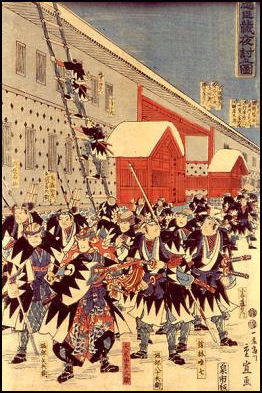

19th century kabuki troupe While Noh was regarded as the official art form of the samurai, kabuki has a tradition of appealing to ordinary people. People wore what they liked and often ate, drank and shouting at performers during the shows. One unique feature about kabuki is that it has its own special theater. Early kabuki plays were performed outside. In the early 18th century puppet play were adapted for Kabuki and special two-story theaters were built with a stage equipped with something called a flower path that extended into the audience. In the later half of the 18th century, sophisticated theaters were built with elaborate machinery that revolved and lifted the stage.

“Kabuki” developed during the more than 250 years of peace of the Edo period (1600-1868). The tastes of the merchant culture that developed during this time is reflected in “kabuki”’s magnificent costumes and scenery and in its plays, which contain both larger-than- life heroes and ordinary people trying to reconcile personal desire with social obligation.

“Sakata Tojuro I (1647-1709) developed the refined and realistic “wagoto” (soft business) style in the Kyoto-Osaka area. The “kabuki” stage gradually evolved out of the “noh” stage, and a draw curtain was added, facilitating the staging of more complex multiact plays. The “hanamichi” passageway through the audience came into wide use and provided a stage for the now standard flamboyant “kabuki” entrances and exits. The revolving stage was first used in 1758. In the merchant culture of the 18th century, “kabuki” developed in both a competitive and cooperative relationship with the “bunraku” puppet theater.

Golden Age of Kabuki

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Kabuki evolved into different branches. In the region of Kyoto and Osaka the inspiration for kabuki was provided by the erotic, hedonistic “floating world” or ukioyo of the “pleasure quarters” of the bigger cities. This life style, with its famous prostitutes and kabuki star actors, has been depicted in thousands of the coloured wood block prints of the period. Another, more powerful and flamboyant style evolved in the first half of the 18th century in Edo, which was the seat of the military government. This aragoto style of acting was influenced by bunraku puppetry. Both bunraku and kabuki shared much of the same repertoire, such as the plays by Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) and many other prolific writers. The types of role and the style of bunraku puppetry influenced many conventions, acting technique, and the facial expression of kabuki. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The years at the end of the 18th century and most of the following century were the golden age of kabuki. Several innovative dramatists widened its repertoire by adding the categories of the jidaimono (history plays) and the sewamono (domestic plays), and several new categories, such as the ghost plays (kaidanmono), noh-based dance-dramas, and the thief plays (shiranamimono) to the two older categories discussed above. Kabuki theaters grew from simple teahouse stages and later wooden structures, reminiscent of the noh stage, into actual theater houses with increasingly complicated stage machinery. It became customary to construct a full-day kabuki performance on a double-bill basis, so that often a jidaimono play started the programme and a sewamono play ended it. **

By the end of kabuki’s golden period, most of its various acting styles, with their respective repertoire, were established. Prolific actor families and lineages, who specialised in certain styles and plays, dominated the colourful world of kabuki, much as they still do today. From all the four “classical” forms of Japanese theater it was only kabuki that was able to maintain its full popularity during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Noh and kyogen became rarities, while the bunraku tradition was continued mainly in Osaka. Kabuki, however, adapted themes, texts, conventions, and dances etc. from these older traditions.**

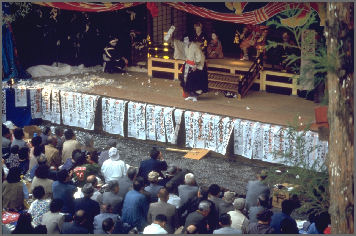

Amateur Kabuki

Amateur kabuki, which is called "jishibai" or "noson" (farming village) kabuki, is most commonly performed in Gifu and Aichi prefectures, where the tradition runs back more than 300 years. Children's kabuki is a feature of an annual autumn festival at Murakuni Shrine in Kakamigahara, Gifu Prefecture. Established in 1877, Murakuni-za is the the oldest existing playhouse for jishibai. Large-scale renovations were carried out over three years from 2007, and the theater has been designated an important national asset of tangible folk culture. [Source: Akira Anzai, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 2011]

Kabuki teacher Ichikawa Fukusho, 76, who directed the children's performance, said, "It's difficult to teach kids delicate movements from scratch, because they don't understand emotions the characters have, like love and giri ninjo." Giri refers to duty or obligation and ninjo means compassion. Takaki Naganawa, 12, played the main character in "Ichinotani Futabagunki Kumagaijinya," a play exploring the feelings of a samurai who kills his own child out of loyalty. "I made four mistakes, but I feel relieved now because I did my best. I'm glad we got such enthusiastic applause from the audience," Naganawa said with a smile.

Kabuki in the 20th Century

In the Meiji era in the 19th century kabuki became more and more of a classical form of drama, rather than a contemporary one. Few new works have been written since then. In recent years plays have been made palatable to audiences. Pieces that used to take a whole day have been shortened to a few hours.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Tokyo (formerly Edo) became the centre of kabuki, and by the end of the 19th century there were three large kabuki theaters. All of them were destroyed by fires and bombings, and only one of them, the famous Kabuki-za, was rebuilt in 1952. Nowadays the National Theater of Tokyo also serves as a stage for kabuki. During the Meiji period, when Westernised forms of entertainment became fashionable, a new type of more realistic kabuki was introduced. It was shin kabuki or “new kabuki”, which never really gained wide popularity. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

From the 20th century until the early 21st century kabuki has definitely remained the most popular form of traditional theater in Japan. But it has not stagnated into being a kind of “museum piece”. Far from that, various, even contradictory, trends can be recognised at the moment. Several remarkable actor-producers have made innovations in order to modernise kabuki, while some other, similarly important artists are digging deeper into its roots. **

“”Kabuki” today is a vigorous and integral part of the entertainment industry in Japan. The star actors of “kabuki” are some of Japan’s most famous celebrities, appearing frequently in both traditional and modern roles on television and in movies and plays. For example, the famous “onnagata” Bando Tamasaburo V (b.1950) has acted in many non-“kabuki” plays and movies, almost always in female roles, and he has also directed several movies. In 1998, the “shumei” (nameassuming) ceremony in which actor Kataoka Takao (b.1944) received the prestigious stage name Kataoka Nizaemon XV was treated as a major media event in Japan. In 2005 another “shumei” ceremony garnered widespread attention when “kabuki” actor Nakamura Kankuro was named Nakamura Kanzaburo XVIII.

“In contrast to the other forms of classical theater, today “kabuki” continues to be very popular, regularly playing to enthusiastic audiences at theaters such as Tokyo’s Kabukiza, Kyoto’s Minamiza, and Osaka’s Shochikuza. Kabukiza, Japan's main “kabuki” theater, was built in 1924, and in 2002 received the designation of a national registered tangible cultural property. (Performances of “kabuki” at Kabukiza have not been held since May 2010 because the theater is being reconstructed. The new theater is expected to open around 2013.)

Kabuki Theater and Props

Special kabuki theaters called “nogakudo” have stages both in front of the audience and along the sides which helps create a bond between the actors and viewers. The interior of the theater also contains a “mawaro butal” (a revolving stage), “suppon” (a platform that rises from below the stage) and “hanamicho” (walkway that cuts through the audience seating area to connect the stage with the back of the theater). Magicians and supernatural beings often make their entrances from trap doors in the hanamichi. Some stages have 17 trapdoors.

In August 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Kabuki actor Ichikawa Somegoro was hospitalized after falling from the stage and has been diagnosed with a bruise to the right side of his head and body, his father's office said Ichikawa fell from the stage while performing at the National Theater in Tokyo. The next day’s show was postponed. Apologizing for the anxiety caused, his father Matsumoto Koshiro, who is also a kabuki actor, said, "I'm relieved the injury was not as serious as we thought." [Source: Jiji Press, August 29, 2012]

Kabuki props are often quite interesting. Flowing water is usually represented by fluttering roles of linen; and creatures like insects and foxes are dangled from sticks or manipulated by helpers who come on stage dressed in black hooded robes so they are "invisible" to the audience. Props often have symbolic meanings. Fans are used to symbolize wind, a sword, a tobacco pipe, waves or food. Sometimes an actor waves a stick below his robes to indicate an erection.

Kabuki Stage and its Machinery

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: During the 18th century, the kabuki stage developed into a complicated “magic box” with several types of curtain, lifts, traps, and even a double revolving stage. In its complexity the kabuki stage can only be compared with the “baroque stage”, which evolved in Europe at approximately the same time. Both of them aimed to fulfil the various needs of the dramas that were performed on them. Both of them aimed to maximise the stage magic in order to amaze the audiences. There are, however, clear differences between the Western baroque stage and the kabuki stage. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The Baroque stage grew out of the European court theater tradition, while the discovery of the “scientific perspective” during the Renaissance was crucial to its development. It led to the type of rather high and deep stage on which the illusions of far distances could be created by manipulating the vanishing point by means of illusory side- and backdrops. Kabuki theater, born in the “pleasure quarters”, on the other hand, has a very wide stage. The almost two-dimensional painted scenery reminds one of the traditional Japanese style of painting, while the wide, horizontal stage opening reminds the viewer of Japanese horizontal picture scrolls. **

The earliest kabuki performances were performed on temporary stages. During kabuki’s early popularity it was performed on wooden structures, more or less similar to the noh stage. By the end of the 17th century the kabuki stage had adopted one of its characteristics, hanamichi or the “flower path”, a pathway which leads from the back of the auditorium to the left corner of the actual stage. Important entrances and exists are made through hanamichi. This brings the actors to the middle of the audience. Important self-introductions are also performed on it and thus special acting techniques related to hanamichi evolved. The back room, at the back of the auditorium, into which the hanamichi pathway leads, is connected with the backstage area by means of a tunnel, called “hell”. Another pathway, kari hanamichi, may be erected on the other side of the auditorium when the play requires one. **

Quick stage changes were made possible by the means of curtains (maku). The main curtain, striped joshiki maku, is opened from right to left. Other types of curtain are black (invisibility) and blue (heaven). Some of the curtains are dropped onto the floor while a rising curtain is often used in the dance plays. In some cases the changes of set are not hidden from the audience. In fact, they may be the highlights of some plays. For example, during a fighting scene, taking place on a temple rooftop, the whole temple building is lowered by lifts into a huge trap so that the audience may have a better view of the action on the roof. **

Complicated lift and trap systems, evolved through centuries, make it possible for the heavy sets to appear and disappear in the blink of an eye. In the same way, actors, particularly those in the fabulous surprise scenes, may suddenly appear in front of the audience from the most unexpected places. The full-size revolving stage, which was used in Europe for the first time in 1896, had already been invented in the kabuki context in 1758. Soon a dual revolving stage was also introduced. It enabled still more complicated and quick stage changes as well as sensational illusions, such as sea scenes with several moving boats. Illusions form an important element in many of the kabuki plays. One of the most fabulous stage tricks is “riding the heavens” (chunori) in which an actor flies over the stage, or even over the auditorium. Certain types of plays make full use of these stage tricks of the fully developed kabuki stage, while some others use them sparingly, if at all. **

Kabuki Costumes

Kabuki costumes are made with bold colors and patterns, it is said, to heighten the drama of the performance. Some costumes are quite heavy, weighting over 20 kilograms, and have the folds and layers that have to be carefully positioned when the actors sits down. Kabuki costumes are usually discarded after one 25-day theater run because the brilliant colors fade in the bright lights and they smell bad from all the sweat.

While the costumes used in domestic plays are often realistic representations of the clothes of the Edo period, historical plays often use magnificent brocade robes and large wigs reminiscent of those found in the “noh” theater. For “onnagata” dance pieces particular attention is paid to the beauty of the costume.

The female characters generally wear an elaborate kimono and obi. Pleated hakuma trousers are worn by characters of sexes. Actors playing both sexes often have a supported midriff because a straight, curveless figure is regarded the epitome of beauty. Costume changing is regarded as an art unto itself. There are special teams that take care of complete and partial costume changes. Sometimes these are done as part of the performances.

Wigs are essential accessories, with each costume having its own type. Specialized craftsmen shape the wigs to the head, maintain them and prepare them for each performance. Some craftsmen specialize in wigs for a certain kind of character. Most wigs are made of human hair but some are made of horse hair or, bear fur or yak-tail hair imported from Tibet. In the old days some wigs were made by painstakingly sewing on one hair at a time.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Costuming in kabuki is called isho. The kabuki repertoire covers numerous types of plays; some of them narrate the feudal intrigues of the past (jidaimono), some recount the everyday life of the Edo period (sewamono), and some depict ghosts and supernatural beings. Thus kabuki also uses several types of costumes. The costumes of jidaimono plays resemble heavy dresses of old times, much like noh costumes. Men often wear wide, skirt-like trousers and they have wide, stiffened shoulder extensions. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The realistic costumes of the Edo period are used in the sewamono plays. The most modest of them are the “paper kimonos”, which indicate poverty, while the most splendid are the costumes of the popular courtesans. They consist of several layers of kimonos covered by a heavy outer robe. The lowered collar of the back of the kimono reveals the neck, which has been regarded as a most erotic detail. The costumes may reveal many things and they convey hidden messages. Their colours and particularly their embroidered details, such as various flowers, may have symbolic meanings. By merely opening the hem of a kimono or revealing the sleeve of the lower kimono an actor may give secret messages. A long, highly erotic seduction scene, for example, can be enacted simply by provocatively opening different layers of costuming. **

Thus the handling of the various types of dress forms an integral part of the acting technique. The costume changes are part of the show. There are two types of quick changes, done in full view of the audience. These special techniques evolved as tricks for the transformation pieces (hengemono) in which the main actor appears in several roles and thus the quick changes of costume, and often also the make-up, form the highlights of the play. In some plays, particularly in the dance pieces, the koken or stage assistant, who is behind the dancing actor, pulls cords which hold the outer robe together to quickly reveal the lower garment. This kind of hikinuki quick change can be done when the actor jumps from one role to another. It can also be done just for its surprise effect or to change the atmosphere of the scene. Bukkaeri indicates a kind of “half hikinuki” in which only the garment of an actor’s upper body is changed by the stage assistant. Both hikinuki and bukkaeri are examples of the various stage tricks and special techniques of kabuki, which are always loudly applauded by the audience. **

Kabuki Make Up

One well-known trademark of “kabuki” is the extravagant makeup style called “kumadori” that is used in historical plays. There are about a hundred of these masklike styles in which the colors and designs used symbolize aspects of the character. Red tends to be “good,” and is used to express virtue, passion, or superhuman power, while blue is “bad,” expressing negative traits such as jealousy or fear. The cross-eye expression of the “mie” pose is intended to indicate intense emotion.

Kabuki actors do not wear masks like Noh performers. They cover the faces, necks and hands with white paint and have red painted around their eyes and their lips. The exotic make-up is regarded as 1) a means of elevating a character to mythic status, 2) a way of defining the actions of the character and 3) a method for actors to reveal invisible qualities about themselves. Make-up exaggerates rather than heightens facial lines as a means of creating dramatic expressions.

Emotion is expressed through colors of make up. Red signifies angers. Brown represents selfishness and dejection. Ghosts often have a blue tinge on their face or blue veins sketched in a branch shape. Samurai have white faces with black eye brows and red touches at the mouth. The make-up worm by actors impersonating women consists of idolized feminine features delicately painted into a white base.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The most common make-up (kesho) of the main characters of kabuki is pure white. It is the colour of purity, refinement and aristocracy. Many of the commoners, such as servants and peasants, have more brownish make-up, indicating the tan of people who work outdoors. The white make-up is done by first shaving or pasting the eyebrows, after which the white base is applied. (The onnagata characters have a red base under the white layer.) After that, the eyes are outlined with black and red, the lips painted and finally the eyebrows are marked high on the forehead. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

This type of make-up makes it possible to exaggerate the facial features according to the general flashy aesthetics of kabuki. It also accentuates the facial expression, which dominates kabuki acting so much, and makes it clearly visible to the audience. There are also several, even more stylised, special types of make-up. The most exuberant of them is kumadori, a make-up style that evolved along with the aragoto, or vigorous male characters, invented by Ichikawa Danjuro I. In kumadori, make-up lines which exaggerate the actor’s facial features are painted on his face. Red lines indicate a good character while blue ones indicate an evil character. The actor usually applies his own make-up. In some plays, particularly in the so-called “transformation plays” in which the actor quickly jumps from one role to another, several layers of make-up painted on thin cloth are used in order to change the actor’s appearance.

Kabuki Music

By far the most important instrument used in “kabuki” is the three-stringed “shamisen”. Included in the musical genres that are performed on stage in view of the audience are the “nagauta” (long song) style of lyrical music and several types of narrative music in which a singer or chanter is accompanied by one or more “shamisen” and sometimes other instruments. The standard “nagauta” ensemble includes several “shamisen” players as well as singers plus drum and flute players. In addition to the onstage music, singers and musicians playing the “shamisen”, flute, and a variety of percussion instruments are also located offstage. They provide various types of background music and sound effects. A special type of sound effect found in “kabuki” is the dramatic crack of two wooden blocks (“hyoshigi”) struck together or against a wooden board. Short summaries of a historical play and a domestic play are given below. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Kabuki uses a particular style of shamisen-accompanied narration (gidayu) as well as several types of music, which is divided into two main categories, those of the narrative katarimono and the more lyrical utaimono. The former evolved from the narration and music of bunraku puppetry, while the latter had its origins in types of music that accompanied various dances. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

A third type of music, geza, is provided by musicians half hidden from the audience in a small room on the right of the stage. The dominant instrument of kabuki is the three-stringed shamisen lute. The off-stage geza orchestra, however, uses several other instruments in order to provide changing atmospheres and special sound effects, such as storms, rain etc. In some plays, particularly in the dance plays derived from the noh repertoire, the orchestra and singers sit on platforms at the rear of the stage. However, it is not music alone that forms kabuki’s rich aural world. **

Two types of wooden clappers are used for different purposes. Hand-held ki clappers, with their intensive crescendo, announce the beginning of the play, while the tsure clappers, struck against a board, anticipate and accompany dramatic climaxes, such as the dramatic mie poses. These highlights are also accompanied by the loud, well-timed kakegoe shouts of encouragement and appreciation from the semi-professional kabuki fans. **

Kabuki Performances

Kabuki performers plays ghosts, samurai, fair maidens and demons. They are as much dancers as actors, moving around the stage with highly stylized movements to the sound of wooden clappers, drums and traditional flutes. After a performance they often collapse in a state of physical and emotional exhaustion. Most of the speaking is done by a narrator known as the “gidahu”.

. Describing a death scene “Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami”, Ben Brantley wrote in the New York Times, “The struggle is ornately stylized, a repetitive series of images frozen and fluid. Yet the violence feels more poisonously concentrated than it ever dies in a crime or horror movie. And at least one image — of the victim rising from a brown pool, coated in mud — feels destined to show up in your nightmares.”

“All the characters,” Brantley wrote, “are as mannered and symbolic as figures in Japanese woodcuts, with expressions that even in moments of anguish and ecstacy are fixed, clear and serene. You can determine a person’s essential nature by the curl of his drawn eyebrows or...by the set of his face-concealing hat...Yet the longer you watch the performers, the more you sense complexity beneath the semaphoric gestures and grimaces...The gruff, burlesque humor...melts into a graver psychological landscape that brings to mind the guilty frightened souls of a Dostoevsky novel.”

There is a lot of detail work. Kabuki actors act differently depending on whether they drink hot or cold saki and whether it is drunk from a tea cup or sake cup. Violence is a major part of the action. Some kabuki dramas feature sword-wielding samurai loping of the heads of half a dozen enemies

Special Techniques in Kabuki

One of the most important special techniques of kabuki is mie, a dramatic movement sequence, which ends up in an expressive pose culminating in a highly stylised facial expression with crossed eyes. Mie is performed by male actors, while similar poses, although less stylised and without crossed eyes, of the onnagata female impersonators are called kimari. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

They are the highlights of a play just as the highest notes of arias are in Western opera. These dramatic climaxes are anticipated by wooden clappers and by rhythmic shouts of encouragement (kakegoe) of the semi-professional kabuki fans in the auditorium. The mie poses and their caricature-like facial expression, always applauded by the audience, are like “logos” of the plays. They have been repeated in the old wooden block prints as well as in the modern kabuki posters. **

Another special technique is roppo (six directions), a stylised, exaggerated way of walking typical of the vigorous male characters, which is often seen in the aragoto and jidaimono plays. The roppo, with its powerful arm movements and high steps, is mainly executed on the hanamichi pathway to signify the exit of an important character. The fighting scenes in kabuki are called tachimawari. As in the Peking opera of China, so too in kabuki the battle scenes clearly reflect the techniques of the martial arts. However, in kabuki they are even more stylised than in the fast and highly acrobatic battles of Chinese opera. **

In addition, various weapons and acrobatic somersaults etc. are used in kabuki’s tachimawari scenes, but the scenes are shown as in slow motion in order to let the audience clearly enjoy all their details. Usually the hero conquers his enemies with superior ease without even touching his opponents. With their intensive percussion accompaniment, the scenes are masterworks of group choreography. **

Kabuki Audiences

Japanese often bring food to kabuki performances and social with their friends during the intervals or even during the play. Most people who attend kabuki performance are elderly Japanese or foreign tourists.

Critical moments of a kabuki play are often marked by long pauses known as “kakegoe” in which Japanese fans shout praise and encouragement and think about what has happened in the play.

During some performances shouts come from the audience at specific times. The shouts — also known as “kakegoe” — are carefully timed to coincide with moments of high drama. The shouters often sit in the cheap seats and are known as “omuko-san” (“great distance ones”) but are generally very knowledgeable about the plays and know exactly when to shout.

Super Kabuki and Making Kabuki Watchable

Super Kabuki is a crowd-pleasing style of kabuki developed in the late 1980s that features dry-ice smoke, fancy lighting, and elaborate sets with giant moving spiders and flying foxes and costumed actors doing hand springs across the stage. One Super Kabuki production features a wild fight scene with flying actors in a torrential storm produced with 30 tons of water. Like regular kabuki there are wood-block platers and a hanamichi.

There is also Off Kabuki, which is characterized by improvised, campy, humorous performances in smelly theaters with a low admission fee. Off Kabuki troupes sometimes make so little money, they sleep in the theaters where they perform.

In an effort to generate interest in kabuki among young people, "kabuki appreciation" performances are being staged at high schools and middle schools.

These days theaters with kabuki and Noh performances provide synopses written in English and earphone guides, with detailed English translations that coincide with the action, to help foreign observers. Performances attended by foreigners often include a lecture in kabuki and play that has been shortened to the length of a feature films, about 2½ hours.

Kabuki Themes and Playwrights

Many kabuki dramas have similar themes and plots as western dramas. Common kabuki themes include loyalty, love, honor and revenge and consummating love with suicide. Many kabuki masterpieces are adaption of bunraku puppet pieces.

Kabuki plots are often complicated and involve a coterie of characters The main story usually revolves around a high born young man who falls in love with a desirable courtesan and lower class friends who protect them.

Kabuki's first and most famous playwright is Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), who mainly wrote for bunraku puppetry. He wrote about 100 bunraku and kabuki plays is sometimes called Japan's Shakespeare. Many of his plays are set in Osaka and deal with themes and characters from the commercial and pleasure districts that were close to the hearts of Osakans.

“Although he concentrated on writing for the puppet theater after 1703, Chikamatsu Monzaemon wrote some plays directly for “kabuki” . Around this time, “kabuki” was temporarily eclipsed in popularity by the puppet theater in the Kyoto-Osaka area. In an effort to compete, many puppet plays were adapted for “kabuki”, and the actors even began to imitate the distinctive movements of the puppets. The fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868 resulted in the elimination of the “samurai” class and the entire social structure that was the basis for the merchant culture, of which the “kabuki” theater was a part.

“There were failed attempts to introduce Western clothes and ideas into “kabuki”, but major actors such as Ichikawa Danjuro IX (1838-1903) and Onoe Kikugoro V (1844-1903) urged a return to the classic “kabuki” repertoire. In the twentieth century, writers such as Okamoto Kido (1872-1939) and Mishima Yukio (1925-1970), who were not directly connected to the “kabuki” world, have written plays as part of the “shin kabuki” (new “kabuki”) movement. These plays combine traditional forms with innovations from modern theater; a few of them have been incorporated into the classic “kabuki” repertoire. While remaining true to its traditional roots, both in the staging of the plays and in the closely knit hierarchy of acting families

Kabuki Plays

Kabuki plays were often based on lover’s suicides, scandalous murders and public vendettas that were in the news when the plays were written. They come in wide range of genres. At one extreme of the spectrum are “aragoto” — flamboyant exaggerated tales featuring fantastic characters. At the other extreme are “wagaoto”’subtler, more realistic stories often revolving around the relationship between a man and courtesan,

“Kabuki” plays are divided into three overall categories: “jidai-mono” (historical plays), “ sewa-mono” (domestic plays), and “shosagoto” (dance pieces). About half of the plays still performed today were originally written for the puppet theater. Although historical plays were often about contemporary incidents involving the “samurai” class, the events were disguised, if only slightly, and set in an era prior to the Edo period in order to avoid conflict with Tokugawa government censors. An example of this is the famous play “Kanadehon Chushingura”, which told the story of the 47 “ronin” (masterless “samurai”) incident of 1701-1703, but which was set in the early Muromachi period (1333-1568). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The domestic plays were more realistic than historical plays, both in their dialogue and costumes. For audiences, a newly written domestic play may have seemed almost like a news report since it often concerned a scandal, murder, or suicide which had just occurred. A later variant of the domestic play was the “kizewa-mono” (“bare” domestic play), which became popular in the early nineteenth century. These plays were known for their realistic portrayal of the lower fringes of society, but they tended toward sensationalism, using violence and shocking subjects along with elaborate stage tricks to draw in an increasingly jaded audience. Dance pieces, such as “Kyo-ganoko musume Dojoji” (“The Dancing Girl at the Temple”), have often served as a showcase for the talents of top “onnagata”.

Types of Kabuki Plays

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Kabuki plays are drawn from surprisingly many sources. Many of them are shared with the bunraku puppetry. Thus many famous plays can be seen both on the bunraku and kabuki stages. Two important categories of plays are adapted from the bunraku repertoire. They are jidaomono (history plays) and sewamono (domestic plays). [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The jidaimono plays often refer to the great epics of the feudal period, such as The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari) and the Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari). Thus they are set in the distant past. One reason for this was that the officials of the Edo period were very sensitive to any kind of criticism. So the playwright avoided censorship by setting his dramas in the distant past. The gorgeous style of the costuming of the jidaimono plays reflects the fashions of the early feudal period. In the acting style they are highly stylised. **

The sewamono plays, on the other hand, are more realistic in style, while their costuming is based on the practices of the Edo period. The first sewamono play was Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s (1653–1724) Sonesaki shinju (1703). Like other sewamono plays, Sonesaki shinju recounts the lives of ordinary people of the Edo period, not about mythical heroes of the past. Many of the sewamono plays were based on true events. Those plays about double suicides committed by lovers (shinju) became so popular that they were banned from time to time. **

The third major category of kabuki plays is the shosagoto plays, which concentrate on dancing rather than acting. In fact, dance forms an integral part of most of the kabuki plays, but in the shosagoto plays the dances, performed against beautiful backdrops, are the main content of the plays. Most of the kabuki plays, which were adapted from the noh repertoire during the Meiji period, belong to this category. **

Prolific actors created new role types with their respective repertoire. Sakata Torujo (1647–1709) was the innovator of the wagoto type, the soft and elegant townsman of the Edo period. Wagoto is the main character of many kabuki plays. Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660–1704), inspired by a certain bunraku puppet type, developed the flashiest of all the kabuki male characters, aragoto, the powerful larger-than-life type, full of energy. It also demanded new plays in which aragoto would be the leading character. An illustrious member of the Ichikawa family, Danjuro VII, began the tradition of compiling collections of plays favoured by an actor lineage, in this case the Ichikawa family. His Eighteen Favourite Plays (1840) served as inspiration for several later collections compiled by other kabuki families. **

Kabuki plays can also be categorised according to their themes. There exist, for example, plays based on the older noh and kyogen repertoire, which are called matsubamemono. Plays in which there is a vendetta are referred to as sogamono, plays involving lovers’ suicides are called shinjumono, ghost plays are referred to as kaidanmono, while plays dealing with the lives of famous thieves are called shiranamimono etc. **

Hengemono or the “transformation pieces” is in a category of its own. They are often dance plays in which the main actor assumes several roles in succession. Mostly they involve supernatural beings such as various ghosts. Shin kabuki refers to the modern kabuki pieces of the Meiji period in which stage realism was favoured and from which many of kabuki’s special features and stage tricks were eliminated. **

Famous Kabuki Plays

Famous plays include Monzaemon's “Shunkan”, an 18th century drama about a landlord who has to decide whether to free his subjects or save his own life; “Tsuri Onna” ("Fishing for a Wife"), a play written in 1902 about a foolish man who sets off on a journey with some devious servants to find a beautiful wife; and “Koihkyaku Yamato Orai” ("Courier from Hell"), about a courier who is forced to commit double suicide with his courtesan because he breaks open a sack of money he is holding.

Among the most popular plays are “Kanadahon Chushingura”, the story of 47 samurai who avenged the death of their lord; Shin Sangokushi, an adaption if the Chinese historical epic "Romance of the Three Kingdoms"; “Kyoto Ningy” ("Kyoto Doll"), a Japanese pygmalion story; “The Love Suicide at Sonezaki”, a low-caste Romeo and Juliet drama based on a true story involving the love between a prostitute and a clerk at a soy sauce company; “Renjishi”, a parable about a lion who throws his cub off a cliff and will rear him only if he strong enough to climb back up; and the “Tale of Genji”.

“Migawari Zanzen” (“The Zen Substitute”) is widely regarded as one of the most accessible plays. First performed in 1910 but adapted from a kyogen farce dating to the 15th century, it isa comedy rich in sex, deception and marital problems. The plot centers around a lord who wants to visit his courtesan but has difficulties doing so because of his possessive, suspicious, shrewish wife. His solution: pretend he is doing zen mediation, have his servant switch places with him and have a night of pleasure with his courtesan.

Tale of the 47 Loyal Assassins

One of the most famous events in Japanese history was the mass suicide of 47 samurai in 1702. Known as the “Tale of the 47 Loyal Assassin” or “Churshingura”, it has been the subject of many “kabuki” dramas, “bunkara” puppet theaters, children's books, bestselling novels, movies and television mini-series and documentaries.

The series of events that led to the mass suicide began when Kira Kozukenosuke, an evil warlord and senior official in the Tokugawa shogunate, picked a fight with a daimyo named Asano, who grazed the forehead of Kira with his sword in a fit of anger in a corridor of Edo castle. Such an act was strictly forbidden in the castle and Asano was forced to commit suicide or be killed by Kira's men, depending on the version of the story. Knowing the Asano's death would probably be avenged Kira fortified the walls of his castle and tripled the number of men protecting it.

Forty-seven samurai loyal to Asano vowed to get revenge but they waited for two years and acted like drunken fools, ignoring their wives and children and even failing to show up for the burial of Asano, during that time to make Kira think they were too consumed in drowning their sorrows to be concerned with revenge.

On December 14, 1702, the 47 samurai broke into Kira's Tokyo fortress. Clad in a black-ninja suits with white trim, they approached the castle, running over snow barefoot to remain quiet, and cut up the defenders of the fortress with their tempered steel swords. [Source: T.R. Reid, the Washington Post]

Kira was captured in an outhouse, and beheaded. After marching through the streets of their hometown before cheering crowd, with Kira's head, the 47 samurai lined up in a row in front of Asano's tomb, announced the successful completion of their mission and all 47 of them committed seppuku (ritual suicide) as a punishment for their act of violence.

More Kabuki Plays

Many famous kabuki plays were also famous bunraku plays One of the most famous plays, “Kanadehon Chushingura” (1748) is a 10-hour tale with 10 acts and a prologue. Based on a real event that occurred in 1702, it is about 47 samurai who avenged the death of their lord and then committed suicide. “Sonzezaki Shinju” climaxes with a double suicide and is based on a real story.

Other well known plays include “Shinju Ten ni Amijima” (“Love Suicides at Amijima”) and “Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura” (“Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees”). “Imoseyama Onna Teiken” by Chikamatsu Hanji is sometimes referred to as Japan’s “Romeo and Juliet” even though the reconciliation to two feuding families through the death of a young couple is only part of a story filled deceit, bullying and jealousy. Central acts in the story are the killing of a daughter by her mother and the stabbing death of a jealous woman with a magic flute so her blood can mixed with that of a deer to break the spell protecting an evil leader who controls Japan after his father’s suicide.

“Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura” is a historical play dealing with the lives of samurai and aristocrats often based on real events from the war between the Heike and Genji clan. First performed in 1748, it takes place at the end of the 12th century, after the Heike have been defeated by the Genji. The victorious forces were led by Yoshitsune, the half brother of Yoritomo, the head of the Genji clan. Yoritomo is jealous of Yoshitsune’s success and orders him killed, Yoshitsune flees and is cornered but ultimately escapes with divine intervention. Within this basic stories are numerous subplots involving real historical figures and imaginary characters. Much of the action revolving around three on-the-run generals who stop at a sushi shop and are served up, among other things, the severed head of a servant killed earlier in the day.

“Kyokaku Harusame-gosa” is a drama by Ochi Fukuchi (the pen name of Genichiro Fukachi) based on a real person from 18th-century Edo. The main character, Kyou is the son of a prosperous merchant who has given up his inherence to do battle with rogue samurai. His grievance against samurai goes back to his childhood when Henmi, a high-ranking samurai, used his positions to secure favorable loans from his father. The climax of the story is a final showdown between Kyou and Henmi. Only female intervention prevents major carnage from taking place.

Kanjincho (The Subscription List)

This “jidai-mono” (historical play) is considered by many to be the most popular in the “kabuki” repertoire; it was adapted from the “noh” play “Ataka”. The brilliant warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189) is fleeing north to escape capture by his half brother, Kamakura- shogunate founder Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199), who is unjustifiably suspicious of Yoshitsune’s loyalty. Yoshitsune is disguised as one of the porters of Benkei, his legendary loyal retainer. Togashi Saemon, the officer in charge of the barrier checkpoint at Ataka in Kaga Province (part of present-day Ishikawa Prefecture), explains in an introductory speech that the barrier was established in order to capture Yoshitsune, who is thought to be traveling north disguised as a “yamabushi” (Buddhist mountain ascetic). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Yoshitsune and his men enter along the “hanamichi” (“flower path” ramp leading off stage). They do not have the necessary identification papers, but Benkei, acting as head of the group, tries to convince Togashi that they are collecting donations for rebuilding the temple Todaiji in Nara. Suspecting a trick, Togashi confronts Benkei and orders him to read the subscription list (“kanjincho”) that they would be carrying if they were really soliciting donations. In a famous scene, Benkei takes out a blank scroll and pretends to read. Impressed by Benkei’s skill and devotion, Togashi lets them pass even though he realizes who they are. Then, however, one of Togashi’s men becomes suspicious of the delicate looking porter who is Yoshitsune in disguise. Benkei strikes and berates Yoshitsune in order to convince Togashi that this servant could not really be his master. Again moved by Benkei’s loyalty, the compassionate Togashi allows them to go. Once past the barrier, Benkei begs forgiveness for striking his master, but Yoshitsune praises his resourcefulness. Once the other characters have left the stage, Benkei expresses his joy at their escape in a famous “roppo” exit along the “hanamichi”.

Benten Kozo (Benten the Thief)

This “sewa-mono” (domestic play) is popularly known as “Benten Kozo” (“Benten the Thief”); it was written by Kawatake Mokuami (1816-1893), the top playwright of the late Edo period. Originally consisting of five acts, today Acts 3, 4, and sometimes 5 are performed. The play portrays the exploits of the rogue Benten Kozo Kikunosuke and the gang of five thieves of which he is a member. In Act 3, Benten, dressed as the daughter of a “samurai” and accompanied by another thief posing as her retainer, enters a kimono store, where he pretends to steal some cloth. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“When Benten is falsely accused of shoplifting and struck by a clerk, he and his confederate demand compensation, but their extortion trick is exposed by a “samurai” bystander. Then in one of the play’s most famous scenes, Benten exposes the tattoo on his shoulder and proclaims himself a criminal, in the process changing his speech and manner from that of a high-born young lady to a low thief. In reality, the “samurai” who exposed Benten is Nippon Daemon, head of the gang of thieves, and it was all part of a larger plot to rob the store later. All their plans go astray, and in Act 4 the five thieves flee to the riverbank with the police in pursuit. In another famous scene, the gang members, wearing beautiful kimono and carrying umbrellas, parade from the “hanamichi” to the main stage and introduce themselves while defying the police standing in the background. While seldom performed, Act 5 includes a dramatic scene in which Benten Kozo flees alone to the roof of the temple Gokurakuji, where he first fights off the police and then commits suicide.

Image Sources: 1) Artelino Yoshitaki Utawgawa 2) 12) 13) Japan Arts Council, 3) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 4) 6) Library of Congress 5) Samurai Archives, 7) 8) 9) 10) 14) illustrations JNTO, 11) National Museum in Tokyo

Text Sources: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki]; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014