JAPANESE TEENAGERS AND YOUNG ADULTS

The legal age for adulthood in Japan is 20. There has been some discussion of lowering it to 18 but the idea has received a lot of opposition. One survey found that 70 percent of Japanese opposed it. One study found that if the legal age were dropped to eighteen 191 other laws would be affected, including betting, drinking and signing credit card and loan contract without parental consent.

Twenty is the legal age for drinking, smoking, betting at horse tracks, voting, signing contracts and getting married without parental consent. In terms of criminal justice, juveniles are regarded as people 20 and under. The driving age in Japan is 18.

The rates of crime, truancy and drug use are much lower for Japanese youths than they are for their American counterparts. When teenagers are scolded for something by elderly people such as talking on a cell phone on a subway, the young people often obey immediately and stop the offending behavior with a polite bow.

A survey by the Nikkei Marketing Journal in 2007 found that 34 percent of people in their 20s never or rarely drank alcohol and the number saving money “to prepare for the future” doubled between 2000 and 2007. Another survey found that half of the Japanese people in their 20s are worried about their future.

A survey carried out by the Japan Youth Research Institute involving 7,200 high school students from Japan, China, the United States and South Korea found that Japanese students lack self confidence and express high levels of dissatisfaction with themselves. According to the survey only 36 percent of Japanese students said they were valuable people compared to 89.1 percent among the Americans, 87.7 percent among Chinese and 75.1 percent among South Koreans. Asked if they are satisfied with themselves 78.2 percent of the Americans, 68.5 percent of the Chinese and 63.3 percent of the South Koreans said yes but only 24.7 percent of the Japanese said yes.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Youth Photos globalcompassion.com ; Dark Side of Japanese Youth worldpress.org ; 2009 Time Article on Young Japan time.com/time/specials ; Crisis of Japanese Youth guardian.co ; Japanese Youth and Manners tokyo.metblogs.com ;Youth Fashions japanwindow.com ; Wikipedia article on Freeters Wikipedia ; Japanese Biker Gangs jingai.com

Links in this Website: EDUCATION SYSTEM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SCHOOLS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEACHERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SCHOOL LIFE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BULLYING AND SCHOOL PROBLEMS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FAMILIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE MEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SALARYMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE GIRLS AND YOUNG WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE MOTHERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE WORKING WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KAWAII, GOSU-RORI, AND STREET FASHION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CHILDREN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE TEENAGERS AND YOUNG ADULTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FREETERS, TEMPORARY WORKERS AND FOREIGN WORKERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UNIVERSITIES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Otaku Urban Dictionary urbandictionary.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Otaku Dan Blog otakudan.com ; Otaku Generation Blog generationotaku.net ; Dumb Otaku dumbotaku.com Otaku story in the Washington Post Washington Post ; Otaku History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Academic Pieces on the History of Otaku cjas.org ; cjas.org and cjas.org ; Early Piece on Otaku (1990) informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Man, Nation, Machine informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Otaku from Business Perspective nri.co.jp/english ; Otaku Sites The Otaku, Anime and Manga Portal and Blog theotaku.com ; Otaku World, Online Anime and Manga fanzine otakuworld.com ; Otaku Magazine otakumag.co.za ; Otaku News otakunews.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Spacious Planet Otaku Blog spaciousplanet.com ; Otaku Activities Maid Cafes stippy.com/japan-culture ; Male Maid Café yesboleh.blogspot.com ; Akihabara Book: “ The Best Shops of Akihabara: Guide to Japanese Subculture” by Toshimichi Nozoe is available for ¥1,000 by download at http://www.akibaguidebook.com Akihabara Murders : See Government, Crime, Famous Crimes . Websites: Picture Tokyo picturetokyo.com ; Akihabara News akihabaranews.com ; Akihabara Tour akihabara-tour.com ; Otaku story in Planet Tokyo planettokyo.com

Japanese Girls and Young Women : Danny Choo site dannychoo.com ; Wearing Miniskirts in Winter chinasmack.com ; Yamamba and Ganguro julieinjapan.com ; Paper on Gasu Rori pdf file inter-disciplinary.net ; Lolita Look bookmice.net ; Wikipedia article on Parasite Singles Wikipedia ; Schoolgirls xorsyst.com/japan ; Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential Oxford University Press

Number of New Adults Sinks to All-time Low of 1.2 Million

The number of people aged 20 years old this New Year's Day is estimated at 1.2 million, falling to less than half its peak of around 2.4 million in 1970 for the first time, according to government statistics. Of the 1.2 million people that reached adulthood in the last year, 620,000 are men and 600,000 are women. [Source: Kyodo, January 1, 2012]

The total number of 20-year-olds — the legal age of adulthood — is down 20,000 from last year, hitting a record low for the fifth consecutive year, the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry said. The new adults account for 0.9 percent of the total population of 127.7 million, falling below 1 percent for the second straight year. The government began collecting comparable statistics in 1968.

Social Life of Teenagers in Japan

In East Asia, teenagers socialize less than one hour a day, compared to 2 to 3 hours in North America. Japanese 18-year-olds spend an average of $100 a week on leisure activities, with much of the money coming from allowances provided by their parents.

In one survey Japanese teenagers said they spent only an average of one hour a week dating (compared to five hours a week for American teens).

One 17-year-old told Time, "Usually I go out with my friends, doing karaoke. I hang out in Kyoto because my hometown is dead. Everything closes by 12am, and there's like nothing to do. I don’t eat dinner at home, I just go out with friends instead. O.K. maybe like four times a week. If I don't have to work, I'll go out drinking. My parents know that I drink but they don't care — I don’t have a curfew or anything."

Japanese Juniors and Seniors

Senior (“sempai”)-junior (“kohai”) relations are very important. They manifest themselves between students of different grades in school; bosses and employees at work; and in other hierarchies or organizations, teams and clubs.

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “The line of demarcation between grades becomes even more distinct in Japanese middle school. This is when the senior/junior or “sempai/ kohai” thing, really gets going. This relationship between old and younger students is a vital part of the rest of their educational experience, especially in teams, clubs and “circles'...The basic point: pretty strict attention is paid to the amount of experience a person has” and this has a bearing on the “respect they command.”

In middle school seventh graders are expected to address eighth graders using polite forms of Japanese. Senior-junior relations also may manifest itself with eighth graders scolding seventh graders about something even though the eighth graders are doing the same thing the seventh graders are being scolded for. Most Japanese students accept the situation and don’t try to challenge it.

Japanese Teenagers and Their Parents

Many teenagers get generous allowances from their parents. One young Japanese designer told the New Yorker, “In Japanese families, the ascendance of the father is the usual phenomenon, but after the bubble burst fathers lost their rights and respect. Fathers had to appease their children by giving them lots of gifts.”

Unlike the United States, where grown children are expected to be independent and move out the house when they graduate from university, in Japan it is quite acceptable for young adults to live with their parents if they are single and, in many cases, even if they are married.

Young men and women in their late teen and twenties often retain strong bonds with their parents and get on well with them when they live at home in a crowded space. Parents tend to give their older children space to operate on their own and don’t intervene too much in their private lives.

Japanese Teenagers and Cell Phones

As of early 2008, 60 percent of middle school students had cell phones, and nearly half of them used them to send 20 or more e-males a day but rarely used them to talk, and 96 percent of high school students used them, with high school boys using their phones an average of 92 minutes a day and high school girls using theirs 124 minutes.

A survey in he Osaka area in 2008 found that 18.2 percent of middle school students and 29.5 percent of high school students use heir cell phones mors than three hours a day and found that eight percent of first year female high school students send 100 or more e-mails a day.

Teenagers are the driving force of the Japanese telephone industry. They are especially fond of sending short messages, which many claim are more fun to receive and send than talking face to face. The teenagers are also very adept and using their fingers to punch in the messages. Some girls could even do it with long painted fingernails. Some parents worry the children won't develop verbal communication skills. The journalist Yumiko Sugiura wrote, “It used to be you would get on the train with junior high school girls and it would be noisy as hell with all their chatting. Now its very quite — just the little tapping of thumbs.”

Rather than meeting at a specific place at a specific time, teenagers send repeated message about where they were at a given time and move towards each other like docking spaceships, calling each other and saying "let's meet here" and then calling back and saying, "we changed our minds, let's meet there instead."

Many young people prefer to send text messages to their friends rather than simply call and talk to them. They do this because it is cheaper and they don’t want to bother friends who may be busy. Teenagers have come up with a whole new vocabulary to describe the way they use their cell phones.

Many young people spent small fortunes on accessories, buying stickers, cases and jewelry and cutsie things that can be hung from the cases.

Selfish Youth in Japan

Japanese young people have a reputation for being self-absorbed and inward-looking. In the past few years Britons who have served as hosts for Japanese students studying abroad by their universities complain the students get up when they feel like it, eat meals alone, never try to have a conversation with their hosts, and don’t even say “good morning.” One student who participated in such a program told his professor, “I am paying the cost of my living expenses to the host family. So why do I have to do what they expect?”

Tatsuru Uchida, a professor at Kobe college and author a book called these young people “Karya Shiko” (“Downwardly Mobile Youth”) and their attitude is at last partly derived from being treated as consumers from a very early age. The students with the British host families, he said, “probably feel that they are paying for the accommodation...And they might argue that their contracts don’t say anything about being friendly to their host fairies...Consumption to satisfy one’s desires is a very personal behavior. If you become extremely consumeristic you may cease to see yourself as part of a group.”

Apathetic and Undisciplined Youth in Japan

Japanese teenagers have reputation for being pessimistic, disillusioned, and apathetic. They have been accused of being lazy and lacking the traditional Japanese work ethic and are no longer seem willing to make sacrifices for company, family or country as the parents had.

Teachers interviewed informally by the Yomiuri Shimbun in the late 2000s said high school students today are less ambitious, less attentive to manners, less curious, less resourceful and less likely to get involved in after school activities. They also said they are more likely to freak out over a small things like misplacing an umbrella and that male and female interaction has increased with cell phones and e-mails.

The apathetic attitudes are reflected by a low voter turn out among young people, increases in student truancy and an increasing number of students studying humanities rather than engineering. In one poll of 18- to 24-year-olds, 62 percent said they were politically apathetic. Another study of 16- to 18-year-olds, 85 percent said they were rebellious.

At Coming-of -Age ceremonies in January 2001, young people heckled and threw things at speakers and talked on cell phones during speeches. This resulted in a lot of soul searching and questions about the fate of Japanese youth. In a survey in 2001 of youth between 15- and 24-year-olds, only 28 percent said they enjoy life and only 6 percent said they wanted to contribute to society.

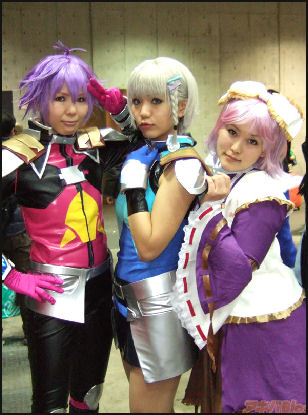

Many young people are defying the tradition of upholding social harmony by doing everything they can to stand out: wearing outrageous clothes, dying their hair shocking colors, riding in motorcycles that make lots of noise.

At Tokyo public high schools three students who became pregnant decided to keep their babies and were allowed to stay on as students, deeply embarrassing teachers and principals who put the blame on for the pregnancy on a popular television show about 14-year-old middle school student who has a baby.

See Girls and Young Women, Women

Reasons for Apathetic and Undisciplined Youth

Many teenagers and young adults grew up coddled in the bubble economy and found a recession waiting for them as they came of age. As a result many are pessimistic about the future. Some problem seems to be classed based. Juveniles from poor neighborhoods are much more likely o get in trouble with law or do poorly in school that those from better off neighborhoods.

One survey found that 60 percent of people in their 20s and 30s are frustrated by life. The novelist Ryu Murakami said that teenagers "can't enjoy the benefits of Japan's past success. Nevertheless they will have to live in this [post bubble economy world] world for a long time. It is very tough and hard to bear.”

One mother told the Daily Yomiuri, “In Japan, adults used to teach children, even other people’s about social rules by scolding them when they were doing things that were wrong.” A salaryman said that these days working parents also hesitate to scold their children because they feel guilty for leaving them home alone while they are out at work.”

Many Young People Have Job Anxieties and Are Pessimistic about Future

In May 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “More than 80 percent of people aged 15 to 29 are very concerned about whether they can earn enough money or receive public pensions after retirement, according to an annual government white paper on children and young people for fiscal 2012. The report also said that younger generations are not optimistic about the future due to unstable employment conditions amid the nation's aging population. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 4, 2012]

The survey found that young people are most worried about their earning power, with 82.9 percent of respondents saying they were moderately or very concerned about whether they would be able to earn enough. This was followed by 81.5 percent who said they were concerned about what would happen to their pension after retirement, and 80.7 percent who said they were worried about whether they can hold down a job. As 79.6 percent of respondents cited worries related to whether they can find jobs or continue to work, the survey revealed a high percentage of people are dealing with economic anxieties, including those related to jobs, income, pension and the state of the economy.

When asked what was the purpose of having a job, most replied with practical answers. At 63.4 percent, the majority replied "to gain an income," while 51 percent said "to support one's lifestyle." Clearly reflecting grim economic and employment opportunities, the survey results showed few respondents thought about their jobs in terms of self-fulfillment. Fifteen percent of respondents said the purpose of a job was to "realize hopes and dreams," with 12.6 percent replying "to support the family" and 11.3 percent replying "to achieve a sense of accomplishment or sense of life purpose through one's work." Only 7.6 percent said it was "to develop one's capabilities.”

Although the overall unemployment rate was only 4.5 percent in 2011, it remained disproportionately higher among young people. The jobless rate was 9.6 percent for people aged 15 to 19, 7.9 percent for people aged 20 to 24 and 6.3 percent for people aged 25 to 29.

Pessimism and Frugality Among Japanese Youth

Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “Japan has already created an entire generation of young people who say they have given up on believing that they can ever enjoy the job stability or rising living standards that were once considered a birthright here. Yukari Higaki, 24, said the only economic conditions she had ever known were ones in which prices and salaries seemed to be in permanent decline. She saves as much money as she can by buying her clothes at discount stores, making her own lunches and forgoing travel abroad. She said that while her generation still lived comfortably, she and her peers were always in a defensive crouch, ready for the worst.” “We are the survival generation,” Ms. Higaki, who works part time at a furniture store, told the New York Times. [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, October 16, 2010]

Hisakazu Matsuda, president of Japan Consumer Marketing Research Institute, who has written several books on Japanese consumers, has a different name for Japanese in their 20s; he calls them the consumption-haters. He estimates that by the time this generation hits their 60s, their habits of frugality will have cost the Japanese economy $420 billion in lost consumption.”There is no other generation like this in the world,” Matsuda told the New York Times. “These guys think it’s stupid to spend.”

Communal shared houses are becoming increasingly popular among young adults in their 20s and 30s. A typical shared house has a six-tatami-mat room for each individual and shared kitchen, bathroom and toilet, living room and dining area. Some companies offer employees this kind of housing, Both single-sex and duel-sex options are available. Many prefer the arrangement to living alone. “I’d die if I don’t have anyone to talk too,” a Kansai resident, transferred to Tokyo for her job, told the Yomiuri Shimbun. Furnished shared houses with a large screen television in the living room go for about $1,000 a month in Tokyo.

Political Apathy by Japanese Youth

Noritoshi Furuichi, a 25-year-old graduate student at the University of Tokyo who wrote a book about how young Japanese were able to remain happy while losing hope told Bloomberg News that he and many other young Japanese say that young people here do not react with anger or protest, instead blaming themselves and dropping out, or with an almost cheerful resignation, trying to find contentment with horizons that are far more limited than their parents”. [Source: Tomohiro Ohsumi, Bloomberg News]

Tomohiro Ohsumi of Bloomberg News wrote: “In such an atmosphere, young politicians say it is hard to mobilize their generation to get interested in politics. Ryohei Takahashi was a young city council member in the Tokyo suburb of Ichikawa who joined a group of other young politicians and activists in issuing a “Youth Manifesto,” which urged younger Japanese to stand up for their interests.

“In late 2009, he made a bid to become the city’s mayor on a platform of shifting more spending toward young families and education. However, few younger people showed an interest in voting, and he ended up trying to cater to the city’s most powerful voting blocs: retirees and local industries like construction, all dominated by leaders in their 50s and 60s.” “Aging just further empowers older generations,” said Mr. Takahashi, 33. “In sheer numbers, they win hands down.” He lost the election, which he called a painful lesson that Japan was becoming a “silver democracy,” where most budgets and spending heavily favored older generations.

“Social experts say the need to cut soaring budget deficits means that younger Japanese will never receive the level of benefits enjoyed by retirees today,” Ohsumi wrote. “Calculations show that a child born today can expect to receive up to $1.2 million less in pensions, health care and other government spending over the course of his life than someone retired today; in the national pension system alone, this gap reaches into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Japanese Teenagers Rejection of Salaryman Society

Many young people look around them selves and don’t like what the see. According to one survey, less than 5 percent of teenagers said the wanted to be a businessmen, bankers, politicians or executives. By contrast 20 percent of young men said they wanted to be beauticians. Other professions that ranked high were television announcer, musician, athlete, video game creator and doctor.

One 17-year-old told the international Herald Tribune, Salarymen "work so hard. And even on the weekends they are too tried to anything. The don't have hobbies. And they don't seem like they are enjoying life."

One 24-year-old man told Time, "I'll never work for a Japanese company...I just want some freedom...I lived in this society where everybody had to follow the rules and...couldn’t seem to adapt.” A high school dropout told Time, "The worst thing in the world would be to be a salaryman."

Young People Abandoning the System in Japan

An online survey by students at Meiji University of people across Japan ages 18 to 22 found that two-thirds felt that youths did not take risks or new challenges, and that they instead had become a generation of “introverts” who were content or at least resigned to living a life without ambition. “There is a mismatch between the old system and the young generations,” Yuki Honda, a professor of education at the University of Tokyo, told Bloomberg News. “Many young Japanese don’t want the same work-dominated lifestyles of their parents’ generation, but they have no choices.” [Source: Tomohiro Ohsumi, Bloomberg News]

Tomohiro Ohsumi wrote in Bloomberg News: “The result is that young Japanese are fleeing the program in droves: half of workers below the age of 35 now fail to make their legally mandated payments, even though that means they must face the future with no pension at all. “In France, the young people take to the streets,” Mr. Takahashi said. “In Japan, they just don’t pay.”

“Or they drop out, as did many in Japan’s first “lost generation” a decade ago. One was Kyoko, who was afraid to give her last name for fear it would further damage her job prospects. Almost a decade ago, when she was a junior at Waseda University here, she was expected to follow postwar Japan’s well-trodden path to success by finding a job at a top corporation. She said she started off on the right foot, trying to appear enthusiastic at interviews without being strongly opinionated — the balance that appeals to Japanese employers, who seek hard-working conformists.”

“But after interviewing at 10 companies, she said she suffered a minor nervous breakdown, and stopped. She said she realized that she did not want to become an overworked corporate warrior like her father. By failing to get such a job before graduating, Kyoko was forced to join the ranks of the “freeters” — an underclass of young people who hold transient, lower-paying irregular jobs. Since graduating in 2004 she has held six jobs, none of them paying unemployment insurance, pension or a monthly salary of more than 150,000 yen, or about $1,800. “I realized that wasn’t who I wanted to be,” recalled Kyoko, now 29. “But why has being myself cost me so dearly?”

Decadent Youth in Japan

In his book “Speed Tribes”, Karl Taro Greenfeld profiles 12 members of the Tokyo fringe: Choco Bon-Bon, the 27-year-old star old porn classics like “Tales of a Hard Banana” doing speed and heroin in hotel room; and Keiko Nakagami, the 21-year-old elevator attendant, donning a form-fitting bodi-con ("body-conscious") dress and dancing suggestively at nightclub; and "Tats" Nobutani, the 19-year-old gang leader, who cruises around Tokyo with "bonfires, bikers in black leather, unconscious girls with their [breasts] hanging out of their tops” with “a bottle of Hennessy going vertical in his mouth."

Book: “Lost Japan” by Alex Kerr (Lonely Planet), “Speed Tribes, Days and Nights With Japan's Next Generation" by Karl Taro Greenfeld.

Juvenile Crime in Japan

See Government, Crime

Efforts to discourage rowdy youths in a Tokyo park by using a device that makes a buzzing noise were terminated because the device didn’t discourage troublemakers from hanging around the park.

Why Japanese Youth Don’t Protest

Noritoshi Furuichi wrote: Protests that began in the United States against societies with large wealth disparities have spread to other countries under the guise of "youth rebellions." One such demonstration was held in Tokyo. I went along to observe it and found there were relatively few people taking part, and almost no young people. That made quite an impression on me.

So why are young Japanese not so eager to stage similar protests? Otake said, “I believe cultural differences explain it. People in the United States and Britain, for instance, are brought up in a culture that teaches them to be independent from their parents when they reach adulthood. They suffer from poverty and social isolation and are subject to humiliation unless they are employed.

The Japanese, on the other hand, allow young people to keep living with their parents even after they reach adulthood, becoming so-called parasitic singles. If this aspect of the culture does not change and young people do not express their anger, a key to solving their problems today will become "anxieties" to be dealt with by their parents and grandparents.

The older generation may believe, "We shouldn't burden and stress our children and grandchildren too much," through contact with them. In response to these concerns, politicians and journalists should reform the social security system, which places heavy burdens on the younger generation.

Image Sources: Ray Kinnane, Tokyo Pictures, Hector Garcia, xorsystblog

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2012