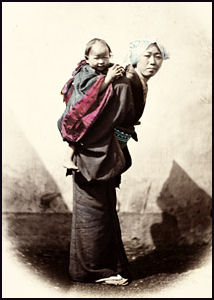

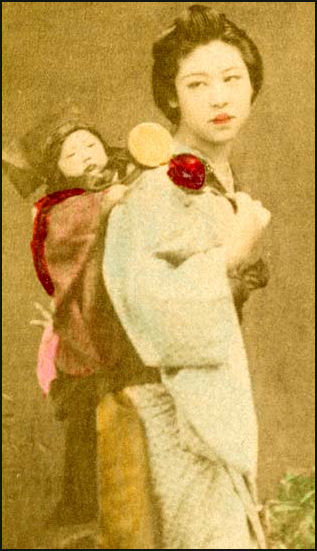

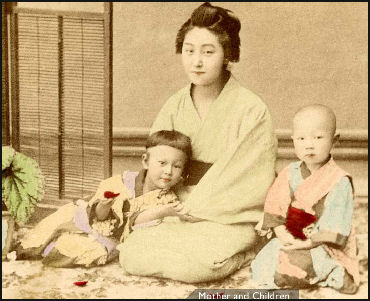

JAPANESE MOTHERS AND HOUSEWIVES

19th century pictures of

Japanese mothers It is not unusual for a woman to marry for security rather than love and end up in a sexless marriage with a husband that is having affairs and keep the marriage going for the sake of her kids.

Today’s children seem more dotted on than ever by their mothers. The national trend towards having fewer children has meant that mothers have more time on their hands to lavish their children with attention.

Japan was ranked the 32nd best place out 160 nations to be a mother in 2010 in annual Mother’s Day commemoration by the charity Save the Children. Norway ranked first.

Good Websites and Sources on Mothers: Research on Mothers of Preschoolers gse.berkeley.edu ; Mothers, Buddhism and Development livingdharma.org ; Parenting Self-Efficacy Among Japanese Mothers highbeam.com

On Women in Japan : Samurai Women on About.com asianhistory.about.com ; Women in Ancient Japan www.wsu.edu ; Japanese Women Get Thinner japanprobe.com ; Japanese Women Don’t Get Wrinkles www.more.com ; Wikipedia article on Women in Japan Wikipedia ; Family, Marriage and Women’s Issues family.jrank.org ;Gender Roles family.jrank.org

Links in this Website: JAPANESE FAMILIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE MEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SALARYMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE GIRLS AND YOUNG WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;JAPANESE CHILDREN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE TEENAGERS AND YOUNG ADULTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Average Age of First-Time Mothers Rises above 30

The number of women who deliver their first child in their early 20s has drastically decreased to one-third of the figure from about 30 years ago, apparently due to several social trends including late marriage, according to population surveys by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry. In 2011, the average age of women delivering their first child exceeded 30 years old.

The average age at which first-time mothers gave birth was 30.1 in 2011, exceeding the age of 30 for the first time, according to Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry statistics. The average age of first-time mothers was 25.7 in 1975, and 29.1 in 2005, rising to 29.9 in 2010. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 7, 2012]

The number of births in 2011 decreased by 20,606 from the previous year to 1,050,698, a record low since the ministry started keeping the statistics in 1947. The drop is partly attributed to a downward trend in the number of women giving birth at 34 or younger. Demographically, births by women under 35 are believed to greatly influence the total number of births.However, the number of women giving birth at 35 or older has been on the rise.

The total fertility rate (TFR), an estimate of the average number of children born to a woman during her lifetime, was 1.39, the same as the previous year. The TFR remained unchanged, even while the number of births declined, because the number of women also decreased.

The number of women that remain single into their 30 has more than doubled since 1980. Although many women do eventually get married (only 4 percent of women over 45 have never been married) many live their lives as if they will never get married. Demographers see this trend as perhaps the primary reason birthrates in Japan have plunged to such low levels.

According to a report “Women on Strike” by the securities firm CLSA because the number of children per married Japanese woman has remained about the same for three decades “the decrease in fertility is due almost entirely to an increase of women of reproductive age not getting married, and not having children.”

Having Children in Japan

There is a Japanese proverb: "a woman without children is not completely a woman." Even so many women these days have decided not to have children. There are relatively few unwed mothers. This is partly because of ease in which single women can get abortions if they get pregnant.

In 1991, the Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology changed the age for "a delivery at an advanced age" from 30 to 35. The announcement paralleled the trend in which women began having children later.

There are Shinto shrines for pregnant women who want a safe delivery. According to an old custom, a woman wraps a plain white cotton cloth around her abdomen during the fifth month of pregnancy to symbolize her wish for an easy delivery. Until recently pregnancy and child birth were not covered by medical insurance because they were not considered "illnesses."

Giving Birth in Japan

Japanese women generally don't take any painkillers, anesthesia or an epidermal (an injection to the spine that numbs the lower half of the body) when they give birth because they believe that these forms of medication are unnatural. Most American women get an epidermal but less than 10 percent of Japanese women do.

Japanese doctors are reluctance to perform Caesareans, and as a result sometimes baby become permanently handicapped from lack of oxygen due to a difficult deliveries that could have been avoided were a Cesarean performed.

Women call their uterus a "baby palace." Sometimes small Japanese women have small vaginas, which are sometimes cut during child birth to make room for the emerging baby. Some women complain that their genitals look ugly after the procedure.

Childbirth has traditionally been viewed a dirty, polluting act. In the old days special “patrician huts” were built for women in childbirth away from their places of residence. Even empresses were sent back to their paternal homes to give birth. In Ise, all babies were delivered on the bank of the river opposite the Shrine.

Until the 1950s most women gave birth at home and midwives were key to delivering babies. These days many nurses are trained in midwifery skills and the number of midwives has dropped to 26,000 in 2004, about half the number in the 1950s.

Nearly half of women give birth to babies in small clinics run by individuals with 19 or less beds. The idea of a father being present at childbirth is still somewhat novel in Japan.

Japanese Housewives

A common view in Japan is that the country's economic miracle was made possible by the nation’s hardworking housewives who made sure their children got a good education and their husbands were well taken care of.

Young housewives work very hard. A study found that on average Japanese woman with children under six spent 3 hours and 2 minutes a day engaged in child care and 7 hours doing housework, compared to 2 hour 41 minutes a day on child care and 6 hours 21 minutes doing housework for American mothers and 2 hour 10 minutes a day on child care and 5 hours 29 minutes doing housework for Swedish mothers.

As they get older and their children take care of themselves, Japanese women have more and more free time, which they often fill with hobbies such as swimming, painting or traditional Japanese activities such as flower arranging and the tea ceremony. "Three meals and a nap" is an expression used to describe the care free existence of housewives.

Book: “A Year in the Life of Japanese Woman and Her Family” by Elizabeth Bumiller (1995, Times Books/Random House).

Survey: Most Women Leave Work after 1st Child

In December 2012, Jiji Press reported: “More than half of working women left their jobs around the time they delivered their first child, according to a government survey. According to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry survey conducted on female employees who delivered their first child in May 2010, 54.1 percent had left their jobs within six months from the time of their deliveries. [Source: Jiji Press, December 15, 2012]

The survey showed 35.3 percent of those who were working full-time said they had to quit their jobs because it was difficult to balance work and child-rearing, while 10.5 percent said they were fired or asked to leave their positions. The largest proportion, at 40.7 percent, said they voluntarily left work in order to fully commit to child-rearing. A total of 25.6 percent said they quit due to health reasons related to their pregnancies.

It is important to provide support for women to continue working to counter the declining birthrate, a health ministry official said. The number of women who left their jobs was down 13.3 percentage points from a similar survey in 2001. A total of 93.5 percent took parental leave, up 13.3 percentage points from the previous poll. Only 2 percent of male employees took leave, up 1.3 points. The ministry sent surveys to 43,767 mothers and received 38,554 responses. Of them, 18,132 delivered their first child in May 2010.

Duties of Housewives in Japan

Japanese housewives have been described as "overscheduled, sleep-deprived and permanently exhausted." They often get up a half hour before everyone else to prepare rice for the morning breakfast, run around all day doing various things to take of the needs of their children, husband and often one of two aging parents, and after checking to make sure their children's homework is done are the last ones to go to bed at night.

The daily activities of a highly-organized Japanese mother include taking care of the family finances, meticulously cooking every meal, keeping the house clean and orderly, attending P.T.A meeting and music lessons, handling important household purchases, making most of the schooling decisions, giving out allowances to their husbands, properly washing the clothes and folding the futons and placing them in the closet.

Some Japanese women dress their husbands in the morning and serve them the choices cuts of meat and special delicacies at dinner. Some even rush onto a train to grab a seat for their husband and then stand up, arms filled with shopping bags, while the husband relaxes and reads a pornographic comic book. [Source: Deborah Fallows, National Geographic, April 1990]

One elderly woman told the New York Times, “I worked hard to raise our children and to help my husband’s business too, but nothing I did was appreciated. For most of my marriage I wasn’t allowed to decide anything, not even what to put in the miso soup. For that I had to defer to my mother-in-law.”

Japanese Mothers and Their Children

Child development in Japan is seen by some academics as one of symbiotic harmony while such development in the United States is characterized more by generative tensions.

Studies indicate that Japanese mothers’ communications with their infants tend to bo oriented toward the mother-child relationship while those of U.S. mothers’ tend to be oriented towards the outside world. Studies have also show that Japanese mothers tend to negotiate with the children on many matters while American mothers are likely to give orders.

A young Japanese child once wrote in a poem: "I am like clay, always being molded into different shapes by mother's firm hands." Japanese mothers are almost never separated from their children. They carry their infant children almost everywhere; and they often sleep with their children instead of their husbands. When the children enter school mothers often sit next to them in the class room. At home, their children have desks outfit with buzzers that alert their mother when they need a snack. [Source: Deborah Fallows, National Geographic, April 1990]

Watching a group of young children at a playground long-time Tokyo resident Lavina Downs wrote in the Washington Post: "None of the toddlers would ever stray more than 20 yards from their mother; an invisible cord seemed to pull them back. The women chatted with each other but rarely spoke directly to their children. Nevertheless, I seldom sensed anything but affection and trust, often spiced with good humor, between mothers and children.” [Source: Lavinia Downs, Washington Post, April 3, 1994]

Mother used to carry their young children on their backs. But these days most urban women anyway use strollers and slings. Young children are often carried everywhere by their mothers on bicycles. Many mothers like to dress their children in hats with ears.

Mothers feel a lot pressure when it comes to childbearing. One child psychologist told the Washington Post, "In Japanese society there is a notion that if you have children, you must get 100 points in raising them. You must be the perfect mother with no mistakes." A Japanese proverb that refers to the importance of childcare in the first years of life goes: "The soul of a 3-year-old stays with him until he is 100."

Disciplining Children in Japan

Japanese children tend to be well mannered. If a child behaves poorly often times the parents are blame more than the child. There are number of expressions that reveal this such as “your bad behavior reveals how badly you were brought up.”

Japanese mothers generally don't scold their children, and try to train their children as much as possible through encouragement and praise. As punishment, they show their displeasure with a mild rebuke or a threat of exclusion. A crying or misbehaving child, for example, is told that everyone is looking and laughing at them so they had better stop. One reporter heard an American six-year-old tell her mother: "If I was gotten mad at by someone, I wish it would be by a Japanese." Even so may Japanese mothers are not adverse to giving their children a good swat if they deserve it.

Children are sometimes punished by being locked out of the house. Children often cry with fierce shrieks when this happens."From our bedroom window," Downs wrote in the Washington Post, "I saw Satoshi, a little boy of 5 or 6, pounding on his front door and frantically screaming to be allowed back in. Over and over again he repeated that he would do what she wanted only 'Please mother, let me in. Please! Please!' I have never heard a child as desperate as that boy. The threat of separation from his mother was profoundly disturbing, and it was clear he was willing to do anything to avoid it."

A survey in 2005 found that 70 percent of parents in their 20s and 40s have a hard time disciplining their children.

Babysitters in Japan

Japanese women have few opportunities to do anything without their children. Grandmothers who live nearby often watch the children while the mother runs errands, Some wealthy Japanese families hire live-in "professional aunts" to help take care of the children.

Babysitters are rare and frowned upon, and the going rate for one is about $15 an hour per child or more. They are used mostly in emergencies. A babysitter for three hours can cost $65 for three hours plus transportation. Teenagers don't babysit because they are too busy with after school clubs or are attending cram school or are studying for entrance exams.

Park Mothers and School Lunches

Because most homes don't have yards and babysitters are a rarity, many Japanese mothers spend their days in their local park with their children. The practice is so common that books, newspapers and television dramas often have references to these "park moms." [Source: Marry Jordan, Washington Post]

Park society has a rigid hierarchal social structure that is reflected in Japanese society as a whole. Every woman has a rank and leaders decide who can be admitted to certain cliques and what activities and fashion are acceptable. A park mom expert told the Washington Post, "May Japanese women have the anxiety of having no identity. For them, the park group, however small, is the start of a place to belong."

In a book on park mom etiquette, “Park Debut”, newcomers to the park scene are advised "take a low posture," "be cautious to an unknown face," and "imitate the elder bosses."

Mothers are often judged by how well they prepare their child's “o'bento”, an "honorable lunchbox" which usually contains fresh peas, boiled eggs, lotus roots, mint leaves, tomatoes, carrots, fruit salad, minced chicken, seaweed is cut into teddy bear shapes and fluffy white rice with a plumb in the middle (symbolizing the rising sun on the Japanese flag).

A sloppy lunch box is regarded as a sign of an uncaring mother. Making bentos has been described as means for mothers “to demonstrate their devotion to motherhood, dedication to heir children’s nutrition and creative skills. One mother told AP, “This is about my pride.”

For women having trouble there is a two volume illustrated book with tips for o-bento making plus numerous websites on the topic. Mari Miyazawa, the host of a popular website “e-bento.com shows mothers how to sculpt dinosaurs from rice colored with egg-yolks with an eye made of sliced cheese and strips of seaweed, teeth made from bits of cheese put in place with tweezers and adorned with star-shaped okra. Decorations often have a seasonal theme: fireworks in the summer, snowmen in the winter. Others recreate cartoon characters or famous people.

Education Crazy Mothers in Japan

The Japanese family is the cornerstone of the Japanese school program, and because the father is rarely home, the mother bears most of the responsibility for making sure her children do well in school. She drills her children, reads to them and works hard to supplement what they are taught in school, and sometimes even attend their classes when they are sick, sitting in special large desks designed for the mothers, so their children don't fall behind. Mothers, not her children, are the ones who are blamed if a child gets low marks in school. [Update: the bit about the mothers attending classes for their sick children is from a Smithsonian magazine article from the early 1990s. It is not done much today. Many Japanese laugh and roll their eyes when I mentions it. It is also worth mentioning there are a lot of Japanese mothers out who are not so engaged in their child's education]

According to a U.S. Department of Education report: "Much of a mother's sense of personal accomplishment is tied to the educational achievements of her children, and she expends great effort helping them. In addition there is considerable peer pressure on the mother. The community's perception of a woman's success as a mother depends in large part on how well her children do in school."

Mothers in Japan are obsessed with their children's education are called Education Crazy Mothers. Describing one, Carol Simons wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "she studies, she packs lunch, she waits in lines to register her child for exams and waits again in the hallways for hours while he takes them. She denies herself TV so her child can study in quiet and she stirs noddles at 11:00pm for the scholars snack...She knows all the teachers, has researched their backgrounds and how successful their previous students have been in passing exams. She carefully chooses her children's schools and juku and has spent hours accompanying them to classes."

Mothers of elementary-school-age children also attend gymnastic, violin and sumo wrestling classes with their children so they can help their kids practice at home. Extreme "education crazy mothers" accompany their sons to their first day of classes at university and even their first day of work after graduation.

Completely Fed-Up Monster Wives and Secret Savings

Television critic Wm. Penn wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “ On Beat Takeshi and Taichi Kokubun’s talk show “ Nippon no Mikata “ Counselor Mayumi Futamatsu argued most marital discord is the fault of "monster wives."...The "monster wife" was characterized as an otherwise "perfect wife." Even if she works outside the home, she still does all the cooking, makes bento box lunches, cleans meticulously and strives for homemaking perfection. Paradoxically, as the pressure and stress build, she is also just one uneaten box lunch or one bit of misplaced clutter away from exploding like a long-dormant volcano.” [Source: Wm. Penn, Daily Yomiuri, November 26, 2010]

“Futamatsu believes the more desirable wife is the "zubora tsuma." Often late-rising, laid-back and not keen on cooking or cleaning, she's far from perfect and readily admits it, but she's quite skilled at getting her husband to pick up the slack. In either case, should divorce ever become necessary, the show claimed the average Japanese woman has "hesokuri" (secret savings) of 3,645,000 yen stashed away.

“Dr. Fuminobu Ishikura chided men who demand to be cared for and catered to constantly. The doctor's prescription was an occasional separation. This was demonstrated by a video of a recently retired man whose wife dashed about endlessly cooking his meals and getting him things. She had reached the "unzari" (completely fed up) stage so the show sent her off to her mother's and filmed him home alone. Unable to even find the soy sauce or open a cup noodle pack on his own, he totally surrendered by Day 2 and was graciously holding her chair for her on her return.”

Housewife Pensions in Japan

The Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry is considering revising the public pension system for company employees and public servants so half the premium payments made by employees with nonworking wives will be regarded as payments by the wives.Under the envisaged system, 50 percent of a husband's employee pension amount would be added to his wife's basic pension payments. [Source: September 30, 2011]

Currently, homemakers who are wives of company employees and public servants are eligible to receive basic public pensions without having paid the premiums. This system of so-called third insured persons has been criticized as too beneficial for homemakers.

When the national pension scheme was launched, homemakers whose husbands were employees were free to decide whether they would be insured by the national pension scheme. However, it came to light that housewives who were not insured by the scheme were not eligible for public pensions after divorce.

A law revision in 1985 aimed to solve this by making such homemakers eligible for public pensions as third insured persons.However, with increasing numbers of single-person households and working couples, the revised system has become subject to criticism, particularly when comparing working women paying pension premiums with homemakers who do not pay premiums.

Wives' “Secret Savings” Rise as Bonuses Shrink

In July 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Japanese wives hold record amounts of so-called secret savings, while their husbands' bonuses this summer sank to record lows, a life insurer survey showed. The average after-tax summer bonus of husbands fell by ¥65,000 from a year before to ¥611,000, the lowest since the survey began in 2003, Sonpo Japan DIY Insurance Co. said. The amount of savings that wives have quietly salted away from their husbands' income averaged ¥3,843,000, up ¥477,000. The figure was the highest since 2005, when questions about such secret savings were added to the survey. [Source: Jiji, July 6, 2012]

“The survey, conducted online during the six days to June 13, covered 500 women aged between 20 and 60 whose husbands are salaried workers. More than 40 percent of the responding female homemakers said they have secret savings, according to the survey.

“Asked how their families plan to use summer bonuses, 72.8 percent of the respondents, the biggest proportion, said they will save them. The second-most popular use was for living expenses, cited by 38.2 percent. Loan repayments were mentioned by 32.6 percent. Multiple answers to the question were permitted.

Single Mothers in Japan

Single parent households in 2000: 5.2 percent, compared to 5.1 percent in 1990 and 9 percent in the United States in 2000.

The number of single-mother households reached 1.22 million in 2003, up 28 percent from the previous survey in 1998. About three quarters of these were the result of divorce. There are few single mothers who have never been married. Less than 2 percent of births occur outside marriage. Cohabitation is also rare and single women almost never adopt.

Single mothers have a hard time in Japan. They have difficulty getting full-time company jobs because of two stigmas: one, they have children, and two, they are divorced. Most get by on part time or poorly-paying jobs and live with their parents. Some widowed mothers live their deceased husband’s family.

The average income in 2007 for single mom household was ¥2.13 million, 38 percent of the national household income average of is ¥5.64 million. A single mother with one child and an income less that $20,000 receives about $400 a month from the government. A women with an income of $20,000 and $30,000 gets $280 a month. Women over 40 often have a particularly hard time finding jobs. Elderly single women get by on pension payments from the government of about ¥120,000 a month.

Women that get divorced or widowed and provide for their family often face economic hardship. There have been cases of women who drove around imported luxury cars when they married who suddenly found themselves with so little money they couldn’t afford a bus ticket to get to a job interview after they got divorced.

Because of the shame factor, couples rarely see each other after a divorce. Sometimes single mothers have a hard time collecting child support payments from their ex-husbands. Many women tolerate affairs and visits to prostitutes by their husbands and put up with bad marriages so they can avoid divorce and the financial precariousness.

Gyaru-Mamas

"Gyaru-mama" refers to mothers who gave birth in their teens or 20s and stick to flashy fashion and makeup despite being busy with child rearing. The word became in vogue about five years ago after it appeared frequently in magazines. Explaining a gyaru-mama is, a 26-year-old gyaru-mama named Aki told the Metropolis: “I think it describes a mother who’s proactive and always trying her best — as a mom, as a wife, and as a woman — in whatever she does, whether it’s raising kids, keeping house or looking good. The woman was 26 and became a mother when she was 21.

Young mothers tend to feel they don't fit in when they attend community-based child-rearing lectures held by their local governments. As a result, they started writing blogs on child rearing, leading the activities to form circles called "Mamasa" (Mamas circles). "Some of those young mothers used to give their parents a hard time when they were middle and high school students," Yamashita said. "They tend to realize the hardships [that their parents experienced] for the first time when they became a mother.”

One being a gyaru-mama Aki, regarded as the queen of gyaru-mamas, said, “I used to get normal mothers talking behind my back about my flashy clothes and nails, but now people understand that this is a gyaru-mama’s right. There was one magazine survey where junior-high and high-school girls picked gyaru-mama as their number one dream occupation. Being a mother isn’t an occupation, but? [laughs] [Source: James Hadfield, Metropolis, December 9, 2010]

On raising her child gyaru-mama style, Aki said she sometimes coordinates her child’s outfit with what she’s wearing. “I get a kick out of coordinating things, so I’ll give us the same hair, go out in matching colors or styles, or sometimes with exactly the same outfits. I’ve got a daughter, so I do “osoro-koode” [outfit matching] a lot. On shopping places Aki said, “The main ones are Shibuya 109 and — I live in Yokohama, so — Yokohama Cial or Sakuragicho. I often go to Sakuragicho, as it’s a really nice place to take a kid. Yokohama gets called the Mecca of Gyaru-Mama, you know.

Activist Gyaru-Mamas

In August 2012, Yoshiko Uchida and Rie Kyogoku wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “A group of young women with long, thick eyelashes and heavy eye-makeup is debating serious matters. The agenda varies, from child rearing and cervical cancer prevention to social contributions. These young women--most of whom dye their hair blond or light brown in the style of so-called gyaru, or gals--are mothers who built a network via the Internet, as they tend to feel isolated in their own communities. [Source: Yoshiko Uchida and Rie Kyogoku, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 31, 2012]

In May, a Tokyo-based group of gyaru-mamas called Stand for Mothers was established as a general incorporated association. The members all met through the Internet and delivered piles of diapers to devastated areas after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Currently, they are trying to make people more aware of the dangers of cervical cancer, as many women in their generation suffer from the disease.

About 20 members from Stand for Mothers joined experts at a recent meeting of the Japan Cancer Society where the members actively participated. "If we can get checkups in a group, we'll be able to look after our children in turn while some are getting the test," one gyaru-mama said. "It'll be easier to understand the process of checkups if it's depicted in manga form," another said.

Ako Hina, 27, who chairs Stand for Mothers, gave birth to a baby boy when she was 20 years old. She is currently raising three children while working as a model for a magazine for gyaru-mama like her. "When mothers like us get together, we can make a difference," Hina said. She said the group wants to tackle problems facing single mothers in the future. The Nippon Foundation financially supports the gyaru-mama group. "They organize from the mothers' point of view, and they're powerful because they take advantage of blogs to spread information," said a spokesperson of the foundation.

The Tokyo-based Japan GalMama Association was established in 2010. The association was launched when mothers who met through the Internet started soliciting consultations from other mothers over child rearing with the aim of preventing child abuse. After the earthquake in March 2011, they received requests from young mothers in quake-hit Fukushima and Ibaraki prefectures to send diapers. Husbands of the GalMama members delivered the relief aid by car.

Aki is the head of “Brilliant Lab,” a “gyaru-mama” circle with 450 members. They have voluntary get-togethers once a month, for things like Halloween and Christmas parties. Explaining why she started the Japan Gal Mama Association, Aki told the Metropolis: For a while now, I’ve been the head of “Brilliant Lab.” Over time, the number of members grew, and we exchanged a lot of information within the group. I wondered if I could do something for parents and children all over Japan, so I set up the association. I also know what a headache it is trying to hold down a job as a single mother, so I thought it’d be good to help single moms look for jobs, too. [Source: James Hadfield, Metropolis, December 9, 2010]

On what the group does, she said: “We have a consultation service on the website to prevent and protect against abuse. We make original T-shirts, donating a portion of sales to [child abuse prevention network] Orange Ribbon, and we’re also helping promote long-term employment for mothers. We now have chapters around the country, and we’re working to give a leg-up to parents and children who are struggling or feel isolated by holding events where they can meet others and have fun.

Gyaru-Mamas Help Design Kawaii Products for Children

Koji Yasuda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The owners of six small factories in Osaka Prefecture have teamed up with gyaru-mamas to develop cute, useful items for children. The collaboration was due to the factories wanting to reduce their dependence on the large companies to which they are subcontractors and the gyaru-mamas' frustration that they couldn't find appropriate products for their children. [Source: Koji Yasuda, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 31, 2012]

To broaden their market, the factories created the Gyaru-mama Shohin Kaihatsubu (Gyaru-mamas product development department) as a limited liability partnership that targets women of child-bearing age. The six factories in Osaka and Higashi-Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, include makers of stationery and tricycles. They previously relied solely on orders from large companies, which demand low prices. As a result, the factories started looking for ways to release products by themselves.

An opportunity presented itself when the president of one factory, Ichiro Kawakita, who runs household goods maker Kawakita, was interviewed by a gyaru-mama magazine. Kawakita asked the magazine's editor to introduce him to young mothers. His goal was to get opinions from consumers of his products. A group of gyaru-mamas reviewed Kawakita's products and gave him ideas on how they could be improved. One gyaru-mama also said she wished companies produced a pair of lunch boxes suitable for a mother and child. "I want a wig so I can change my hairstyle quickly because I'm so busy looking after my kids," another said.

After hearing these comments, Kawakita believed that he could compete in the market by developing products that suited the desires of the gyaru-mamas. Three to six gyaru-mamas meet several times a month to discuss new merchandise for each factory. They also generate discussion about products they see on Facebook and Twitter. In May, they organized an event for mothers where they could discuss new products.

Eighty-seven items were released at the end of July. They include lunch boxes with heart or leopard print patterns priced at 714 yen for a small one and 924 yen for a large size; wigs of various colors and styles priced from 2,480 yen to 2,980 yen; and tricycles priced at 8,190 yen that users can customize by picking from an array of saddle covers and putting stickers around the spokes. "We kept prices down so that the products are affordable for young mothers," Kawakita said.

Atsuko Kai, 28, who has two girls aged 2 and 3, runs a gyaru-mama group in Ibaraki, Osaka Prefecture. "I used to be frustrated because I couldn't find what I wanted to buy," she said. "I'm happy that our opinions and desires are taken into account to create new products.” Kawakita said: "Gyaru-mamas are frank about the good and bad sides of our products. They're also quick to spread information about the products. We'd like to popularize our goods together.” The manufacturers group aims to make 50 million yen of sales each year and plans to release between 150 and 200 items by spring. Items are available at www.gal-mama.com/

Image Sources: Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013