KAWAII

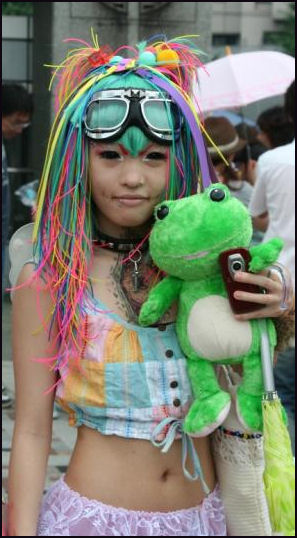

rori-style cosplay “Kawaii” (“cute”) has been an obsession in Japan since the 1960s. Young girls into this look in an extreme sense wear fake fur short coats, have angel wings attached to their backs, have little teddy bears dangling from cell phones and adore anything associated with Mickey Mouse and Pooh-san (Winnie the Pooh). There is an entire magazine called “Cutie” devoted to the “kawaii” look.

Kawaii manifests itself in Japanese anime on television, on road signs with warm and fuzzy bunnies and racoons, and in a seemingly nationwide infatuation with Mickey Mouse and Disney. And its not just a girl and kid thing. Salarymen decorate their cubicles with pictures of teenage idol singers. Shinto shrines sell Hello Kitty key chains. Even the black Mercedes of yakuza gangster have things like a row stuffed Poohs on the dashboard. Some say the Japanese obsession with kawaii began with a Japanese fascination for Petty Boop and really took off with idoloziaion of the American figure skater Janet Lynn.

One reader wrote into the Daily Yomiuri: “To be called cute is a high complement. Cute is cute because its looks harmless but on a deeper level is subordinate. Japan’s love for cute things has been internalized by women and demonstrated in their looks and actions. Because of this, life for women is full of day-to-day and lifelong compromises...Is cute all women are expected to be in Japan? More importantly, is that all they want to be?”

In the late 2000s, 6%DOKIDOKI in Harajuki was a center of Harajuku fashions. Many girls and young women go there to shop for small accessories shaped like hearts, fruits, cakes and ribbons to complete their outfits. The manager of the store told the Daily Yomiuri, “Our concept is “sensational and lovely.” We make products that will make our customers happy when they wear them. A lot of foreigners are shocked when they see Japanese kids using what look like toys to decorate their clothing — but this part of our pop culture,”

The Japanese Foreign Ministry chose model Misako Aoki, singer Yu Kimura and actress Shizuja to be “Kawaii taishi” (“Cute ambassadors”) to promote Japanese pop and kawaai culture abroad. In promotional appearances Aoki is dressed like a Lolita and Fujioka is clad in schoolgirl uniform. Aoki told the Daily Yomiuri, “As a representative of Lolita fashion, I met a lot of women in Paris, San Francisco and South Korea who were into the same fashion. I felt Japanese fashion was spreading through the world and helping young people like Japan.”

Links in this Website: FASHION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HELLO KITTY, JAPANESE FADS AND JAPAN COOL Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE GIRLS AND YOUNG WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE TEENAGERS AND YOUNG ADULTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Youth and Street Fashions: Youth Fashions japanwindow.com ; Japanese Streets japanesestreets.com ; Weird Fashions fashion.3yen.com ; Metrocity Tokyo metrocity.nl ; Harajuku Fashions Tokyo Street Style style-arena.jp ; Harajuku Pictures japanforum.com/gallery ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Japan Guide japan-guide.com

School Girls, Lolitas and Yamambas: Harajuku Style harajukustyle.net ; Yamamba and Ganguro julieinjapan.com ; Paper on Gasu Rori pdf file inter-disciplinary.net ; Lolita Look bookmice.net ; Wikipedia article on Parasite Singles Wikipedia ; Schoolgirls xorsyst.com/japan ; Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential Oxford University Press ; Danny Choo site dannychoo.com ; Wearing Miniskirts in Winter chinasmack.com ; Kawaii Urban Dictionary urbandictionary.com ; Tokyo Kawaii tokyokawaiietc.com ; All Things Kawaii allthingskawaii.net ; asiajam.com ; Academic Article on the Origins of Kawaii kinsellaresearch.com

Kawaii’s 100 Year History

In April 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “An exhibition examining the history of "fancy goods" that have long enraptured Japanese girls indicates that accessories and cute items, which are often described nowadays as "kawaii," were seen as early as the Taisho era (1912-1926). Taisho kara Hajimatta Nihon no Kawaii Ten (Exhibition of Japanese kawaii goods beginning in the Taisho era) at the Yayoi Museum in Tokyo exhibition features the transition of Japan's girly culture over time by displaying various fancy goods created by popular mangaka and illustrators during each historical period. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, April 27, 2012]

“Yayoi Museum curator Keiko Nakamura says: "The phrase 'fancy goods' emerged [in Japan] late in the Showa era [1926-1989]. But actually, kawaii goods enchanted many young girls in the Taisho era." The origins of kawaii goods can reportedly be traced back to 1914, when painter and poet Yumeji Takehisa (1884-1934) opened the paper shop Minatoya Ezoshi Ten in Tokyo's Nihombashi district. It sold stylish stationery such as origami paper with Art Nouveau floral and plant patterns. Designs with Western motifs are said to have become popular in the shop.

“During the early Showa era, karuta picture playing cards designed by mangaka Katsuji Matsumoto featuring the character "Kurukuru Kurumi-chan" were released. After World War II, coloring books by Kiichi Tsutaya and popular illustrators like Rune Naito and Ado Mizumori spread kawaii culture. Later, Sanrio Co., the producer of adorable characters such as Hello Kitty, further disseminated the kawaii trend across Japan. Kawaii has now become a globally recognized word.

Fine Detail of Japanese Kawaii

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, In 2009, I was the producer of a cultural exchange project taking fashion around the world with Misako Aoki, a government-designated "kawaii taishi" (cute ambassador). Girls overseas were wowed by her beautifully decorated cell phone and digital camera. Although girls overseas applied "deco" art to their own cell phones and cameras, their work was far behind Japanese creators'. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, June 22, 2012]

“The Lolita fashion that Aoki was wearing was another product of Japanese creators. Japanese Lolita costumes are so elaborate in terms of the patterns and lace, but ones made abroad don't have such detail. It's easy to distinguish domestic costumes from those made overseas. Japanese creators' ability to pay attention to details is an indispensable property for this country. At the same time, such art cannot be carried on solely by creators, it also must be supported by consumers.

“The foreign women who "want to become Japanese" share the spirit of being creative through their own outfits and the desire to differ from mannequins displayed in shop windows. The mutual relationship between creators and consumers helps Japan stand out and brings benefit to the country.

Kawaii Stocking Art

In July 2012, Tomonori Takenouchi wrote in Yomiuri Shimbun, “A galaxy of stars shooting down long slender legs, a lipstick mark on a knee and Mickey Mouse peeking around a calf--stockings bearing every design imaginable have become a must-have fashion item for Tokyo women this summer. A 19-year-old university student wearing a short lacy dress and a jacket topped off her ensemble with stockings featuring a red heart just above the ankle. The heart bears the message, "Love Me." "The heart accentuates this rather simple outfit," she said. [Source: Tomonori Takenouchi, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 27, 2012]

An 18-year-old vocational school student who was shopping recently in Jingumae in Tokyo's Shibuya Ward, was wearing stockings with a line of origami cranes on both shins. She showed off the black and red paper birds by wearing black short pants and laced platform shoes. "I have about 10 pairs of stockings with different patterns. I sometimes coordinate my outfits based on my stockings," she said.

“Among the other designs I spotted on stockings were an illustration of a face, anime characters and swirling colors. Many of them were priced between 1,000 yen and 3,000 yen a pair. According to a leading stocking maker, the leg coverings have become popular especially among young women since several magazines reported extensively that they can help make legs more shapely and appear smoother by concealing pores. Advanced manufacturing technology has produced extremely transparent stockings that look like bare skin. Plain types and stockings with painted-like designs are available. Short pants and skirts are still in vogue among young women. "Decorating" their legs with stockings looks likely to become part of "the look" this summer.

School Girl Chic in Japan

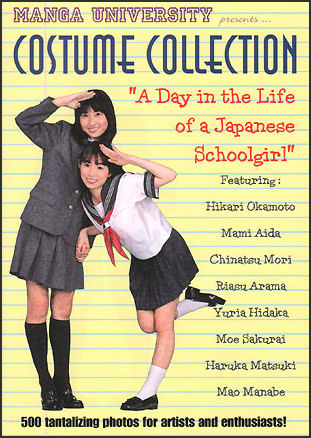

School girls are fashion trendsetters in Japan and their school uniforms are fashion statements unto themselves. There are stories of high school girls picking the high school they attend simply because they like the uniform.

One of the biggest fads in Japan in the mid-1990s was Ruusu sokkusu, baggy knee-high socks worn by schoolgirls and held in place with special glue that was applied with a deodorant-like roller stick. In one survey, 81 percent al all school girls interviewed said they had worn the socks at one time. Other clothing fads from the same period included platform sneakers, knee-high boots, and glued on bras.

There are entire stores such as Spice Candy in Shibuyi, Tokyo that specialize in the school uniform look. Girls and even mothers of girls that shop there think that a sexy school uniform will help them attract guys. The clothes the shops sell are not real uniforms but one that have been jazzed up and given elements of cuteness. Mother like the shops because at least their daughters don’t dress like tramps.

There are also pre-teen magazine that give a lot of attention to school uniform look. Just look at Quentin Taratino’s’s “Kill Bill” which gave Japanese schoolgirls a prominent role to ses how fashionable school girls have become. Even the uniform-making companies have capitalized on the opportunity of producing uniforms for the fashion market as well as the school market and developing tie ins with designer brands such as Hiromichi Nakano and Olive des Olive.

The fake school uniform business is estimated to be ¥40 billion a year. Some girls can’t wait to get home to change out of the real school uniforms into fashionable fake uniform and then head to streets to shop, hang out, pose or head to a club or karaoke to party.

The Japanese schoolgirl look is becoming increasingly popular abroad. In places like Barcelona you can find high school girls dressed in “nanchayye sifuku” (pseudo school uniforms) with Japanese-style accessories, wearing the uniforms in ways popularized in Japan. One Chinese girl told the Yomiuri Shimbun that Japanese school uniforms are like “something from a fantasy” and “symbolize freedom.”

“Japanese Schoolgirl Confidential” by Brian Ashcraft and Shoko Ueda. Ashcraft is a contributing editor for Wired magazine. Ueda is his wife. Based in Osaka, they “bring us a surprisingly capacious work that covers every permutation of the uniformed femmes in manga, anime and flesh and blood live action, fatal or not, even recording the history of the Sailor Moon-style uniform itself, imported from the United States by a fast-militarizing Japan at the turn of the century,” Roland Kelts wrote.

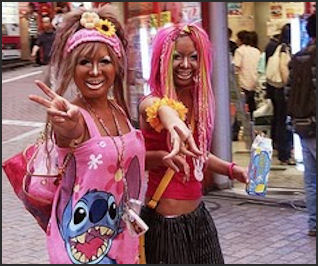

Yamamba and Ganguro

“Yamamba” ("Old mountain hag") and “Ganguros” ("black faces"), or “gyaru” for short, are names given to girls who have orangish, tanned faces and wear white lipstick and eye-shadow, streaked orange hair, thick make-up, colorful tops and miniskirts and massive platform shoes. They are often seen in groups of four or five, chatting on sequin-studded cell phones or applying polish to their oversized fake nail. Some have their faces painted like pandas or goblins and look sort like science fiction versions of the Supremes.

“Yamamba” ("Old mountain hag") and “Ganguros” ("black faces"), or “gyaru” for short, are names given to girls who have orangish, tanned faces and wear white lipstick and eye-shadow, streaked orange hair, thick make-up, colorful tops and miniskirts and massive platform shoes. They are often seen in groups of four or five, chatting on sequin-studded cell phones or applying polish to their oversized fake nail. Some have their faces painted like pandas or goblins and look sort like science fiction versions of the Supremes.

According to 2002 research by Tadahiko Kuraishi of Kokurgakuin University ganguros “appeared suddenly in Shibuya in 1998" and “were covered by the various media. Mostly in their mid-to-late teen, with the majority being 15- to 18-year-old high school girls from Tokyo, China and Kanagawa areas. Their hair is either dyed brown or bleached white, and their faces are painted or tanned a deep brown black...Group movement is fundamental.”

For a while it seemed that the ganguro movement was a fad that would only be around for a couple of years. But these girls have endured and are seen in Osaka and other cities as well as in Tokyo. In Shibuya gyaru-circles have been formed. The leader of one called Angeleek told the Asahi Shimbun, “We’re as gyaru as you can get. There are other gyaru circles here in Shibuya, but we’re what they aspire to be.”

There are said to be 300 gyaru circles with 10 to 15 members each for a total of around 4,000 gyaru in the Tokyo area. The mecca for them is the 109 and 109-2 shopping emporiums in Shibuya. They have a bad reputation. Many shopkeepers and restaurant owners don’t want them in their establishments. Some are regarded as shoplifters, drug users and “enjo-kosai” (schoolgirl prostitutes).

Angeleek is said to have 400 members. They organize dances, make up lessons and hold regular meetings and have male support groups. Many members aspire to be hair stylista, make up artists or nail artists. Some spend ¥30,000 a month on make up and accessories. When they go out they mainly walk the streets and alleys to be stared at and hang out at fast food restaurants, ordering a minimum of food and bringing their own drinks.

Among the most popular magazines for Tokyo “gyaru” is Koakuma Ageha, whose name roughly translated to “devilish butterfly.” It is packed with information about fashion, hairstyles, accessories and shoes for women into the “gyaru” look. With a circulation of 350,000, it is aimed primarily at bar hostesses but has broad readership that includes school teachers and office workers.

Shibuya-gyaru have been recruited by local rural governments to help promote rice among young people and have been hired by the Japanese foreign ministry to promote Japan — and Lolita fashion in particular — as cool.

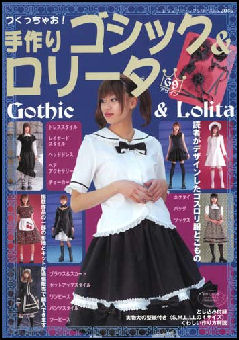

Gosu-rori Look

“Gosu-rori” is a street fashion unique to Japan. A colloquial abbreviation of the terms “Gothic” and “Lolita,” it describes teenage girls and young women who merge punk fashions with the little girl look to end up looking like vampires dressed like Goldilocks. The style is associated with Harajuku, Tokyo, where there a number of boutiques that specialize in Gosu-rori clothing and accessories. A gallery show featuring the fashion was call “GOTH: Reality of the Desperate World.”

“Gosu-rori” is a street fashion unique to Japan. A colloquial abbreviation of the terms “Gothic” and “Lolita,” it describes teenage girls and young women who merge punk fashions with the little girl look to end up looking like vampires dressed like Goldilocks. The style is associated with Harajuku, Tokyo, where there a number of boutiques that specialize in Gosu-rori clothing and accessories. A gallery show featuring the fashion was call “GOTH: Reality of the Desperate World.”

The term “Lolita” comes from Vladimir Nabakov novel’s about a middle-aged man’s obsession with a pre-teenage girl and is used to describe women that dress up like little girls or dolls. Gothic original described a style of cathedral architecture in 12th to 15th centuries and was used t describe a genre of horror and fantasy novels in 18th and 19th century that included Bram Stocker’s “Dracula” and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”. Among the punk generation “goth” has come to describe people that dress in a dark manner that calls to mind vampires and monsters. As a fashion is has origins with the Glitter rock and punk scenes in Britain in the 1970s.

Among the fashions that are well-represented in Harajuku are traditional kawaii, decora, Lolita, Gothic, Gothic Lolita, Cyber-Goth, punk, rock and club. The modern kawaii look is associated more with Shibuya’s 109 and the Shibuya Girls Collection.

The Gothic look in Japan is alive as a street fashion and the elaborate stage costumes and make-up of glam rock bands known in Japan as Visual-Kei.

Lolita Look

Lolita

Some Gosu-rori emphasize the Lolita look, other the Gothic style, with the Lolita look being particularly strong and manifesting itself as girls in French maid outfits or schoolgirl uniforms. The Lolita look emerged in the 1980s and merged with Gothic and punks fashions and a time when these looks were emerging with cyber fashion in Europe and North America.

The Lolita look features frilly Rococo-inspired dresses paired with platform shoes. Although Lolita style is a reference to the Vladimir Nabokov novel “Lolita,” its look is more covered-up Victorian schoolgirl than skin-baring teenage vixen. A popular Lolita activity is sitting around a table enjoying tea and cake.

In its most elaborate form Gosu-rori girls dress in skirts that flair wide at thigh level with the help of hoops, petticoats and panniers, and wear towering platform shoes and frilly blouses augmented by bows, ribbons, ruffles and taffeta. Some hairstyle are works of art unto themselves, piled high with bangs and curls. Some wear maid-like head accessories, Other don tiaras or even crowns

The Gosu-rori look has become entrenched enough that are Gosu-rori magazines and lines of clothes by designers such as Baby, Angelic Pretty and Stars Shine Bright that specialize in the look. Yusuke Tajima, editor of Kera, a magazine devoted to Gosu-rori, told the Daily Yomiuri, “With the birth of the Gosu-rori category, Lolita attracted further attention, not only as a genre of fashion but also as a lifestyle as a whole...Gosu-rori fashion with the taste of “kawaii” must have shocked people in the West as it is clearly different from [earlier] Gothic fashion, with its dark flavor.”

Angelic Pretty designer Asuka told the Daily Yomiuri, “What we design is not moderately kawaii or sweet but extremely kawaii or sweet.” Pink is often their color of choice. At a Gosu-rori fashion show all the Angelic Pretty models dressed in pink and carried a stuffed animal, bouquet or flower basket to enhance their girlish image.

One girl who dressed in the “fairy” style complete with a billowing tutu and head-to-toe ribbons told the Daily Yomiuri, “A lot of people look back at me and talk about my outfit when they pass me on the street, and that can be a bit uncomfortable.” She said she dressed the way she did for the style not the attention.

Although the they have their origins elsewhere school uniforms and Lolita fashion have become are associated worldwide with Japan. One Lolita group in South Korea has 1,800 members. Another in Brazil has 2,000 members. There are also groups in Barcelona, Moscow and Paris.

Fascination with Lolita Fashion Abroad

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: If Japan's so-called Lolita fashion and visual-kei are inspired by, and based on Japanese people's fascination with the West, Western, or white culture, why do young people overseas find these subcultures "cool" or "kawaii"? Put simply, Lolita fashion was created by Japanese designers who drew inspiration from the fashions of the French aristocracy, in particular Marie Antoinette. But when French people--of all ages--are asked about Lolita style, they say it is "made in Japan." These days, Lolita fashion is recognized by many people overseas as being distinctly Japanese. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, October 14, 2011]

In spring 2009, when I was taking a stroll with a Japanese fashion designer dressed in one of her own Lolita creations in Aix-en-Provence, France, a man selling old books came up to us with a big smile and a somewhat surprised look on his face. "Are you a real Japanese Lolita? Would you mind having your picture taken with me?" he asked. It wasn't the only time my designer friend would receive such a request. That evening, we ate at a restaurant. At one point the chef excitedly burst out from the kitchen and asked the designer if he could take her picture and display it on the restaurant's wall.

Japanese people wonder why these subcultures are thought to be uniquely Japanese when they have drawn inspiration from overseas. But young people abroad actually don't understand this logic. When asked the appeal of Lolita, anime and visual-kei, they almost always describe these subcultures as "original" and "unique." They find it hard to believe that the Japanese copied aspects from their own cultures when creating Lolita fashion, visual-kei and animation.

Yet one of Japan's greatest strengths is its innovation; its people have long been inclined to adapt aspects of other cultures into their own. Japan's isolation is probably why they don't recognize Japanese subcultures as being "reimported" from the West but as something entirely original. For example, French Lolita girls claim to know the origins of Japanese Lolita culture. However, they believe Lolita fashion is a Japanese invention, and has not been influenced by their own culture.

Japanese Maid Culture Abroad

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in The Daily Yomiuri, “Interest around the world in the Japanese maid cafe, a symbol of otaku or "geek" culture, may be much greater than Japanese people think. At least I've come to think so during the past several months. I went to Changchun in northern China in early June to attend the Changchun International Comic and Animation Fair. While strolling around the venue, I came across Chinese women clad in maid costumes handing out flyers advertising a maid cafe that will open in Changchun in August. The wording of the flier, written in both Chinese and Japanese, was amazing.It said, "My love for my master will never ever change, even if I go to hell!" I believe the Japanese words were a direct translation of the Chinese. Still, I never thought I would be given such a flyer from a "maid" in northern China.

It was not that Japanese people were around at the venue. In fact, there hardly any Japanese there at all. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai. Daily Yomiuri, July 8, 2011]

At the first Kintoki-Con in Sacremento, held in June as well, I also found a maid cafe. The event, held at the Hyatt Regency hotel, introduced Japanese pop culture, and the cafe on the hotel's first floor had been temporarily transformed into a maid and butler cafe. At the entrance, a maid welcomed customers with "okaeri nasaimase, goshujin-sama" (welcome home, my dear master), in Japanese.This is a universal practice. Whether a cafe is in Taipei, Shanghai or Beijing, and whoever the customer, maids deliver the greeting in Japanese. So it happens that a Chinese maid greets Chinese customer in Japanese."It just doesn't sound right if it is not Japanese," both maids and maid cafe customers say.

Asked why they wanted to be a maid, most of the women answer, because it's "kawaii." I became deeply aware through my cultural diplomacy efforts that kawaii, or cuteness, often works as the standard of value for many girls all over the world. And now it is becoming part of their common sense that maids (and maid costumes) are also kawaii.

Kawaii structures how they see the world: they notice something as kawaii, and make a move before thinking it out thoroughly. But I don't see such attitudes as a negative thing. Sharing a sense of values--including a sense of what's cute--beyond national boundaries should signal hope for the future of a world ridden with strife and difference. There should be a variety of means for realizing this sharing, and in that regard, the good, the true--and the cute--are equally worthy of our esteem. If the young people of the world find the Japanese culture of maid cafes kawaii and value it, I think the Japanese should embrace it.

An American professor I met in Hawaii who teaches a seminar that explores the theme of maid cafes said the spirit of maid cafes reflects Japanese people's idea of courtesy.

Dokusha Models

Yamabas Takamasa Sakurai wrote in The Daily Yomiuri, “A current characteristic of Japanese women's fashion magazines is the popularity of so-called dokusha (reader) models. They closely resemble professional models but are amateurs who represent the readers of the magazine. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, The Daily Yomiuri, August 5, 2011]

Thanks to their practicality, Japanese women's fashion magazines are very popular in countries like China and Taiwan. Many young women in these countries buy Japanese fashion magazines to help them more fashionably coordinate clothes they already have or to get ideas on what to buy. Reading these magazines is not like admiring items in vogue and thinking they are very special and of another world.

Dokusha models support this ethos. They do not have well-proportioned bodies like supermodels. They are not particularly tall, either, meaning the clothes they wear so well can fit readers, with a little effort. U Kimura, who often appears in the fashion magazine KERA, is a dokusha model. She was a government-designated "kawaii taishi" (cute ambassador) in fiscal 2009, and I toured European nations and China with her as a producer of these promoters of pop culture.

In Paris, Kimura featured in a fashion show whose concept was Harajuku, Tokyo, alongside many top models working at the seasonal Paris Collections event. Needless to say, the professional models looked great on the catwalk. But local young women cheered and applauded more when Kimura appeared. They were just like the women who are fascinated with the pages of magazines on which dokusha models strike poses.

It may be safe to say that the current enthusiasm toward dokusha models reflects a shift: Fashion is no longer enjoyed by the eyes of others, but by those actually wearing the clothes. This suggests young women are choosing what they actually wear from fashion magazines, rather than merely look at fashion presented by stylists and worn by professional models.

JAPANESE FASHIONISTAS

Japanese fashionistas are often teenagers or people in the 20s who live at home and spend a considerable portion of the money they get from allowances and part time jobs on fashions. They often spend $500 to $1,000 a month on clothing and accessories.

Most fashionistas are girls. The main base for them in the early 2000s was 109, a ten-story building filled with small shops with the latest in trendy clothes. Boys generally are not welcome. Many of the clothes are designed by D.J.s and musicians and have tie ins with local punk and alternative rock groups. There is an entire floor for girls between 12 and 15. The Egoist is another store popular with teenage girls. It popularized trends like the “Rodeo Girl” and “Sexy and Boyish.” There even the salesgirls have became fashion icons with their own followings.

In recent years, the fashion market for female betweenies (girls aged 9 to 14) has soared as young girls became more fashion conscious and their parents, grandparents and other relatives have become more willing to indulge them. One clothesmaker told Reuters, “Mothers now take pride in having cooly dressed daughters, their little princesses.” This is far cry from the old days when children wore hand-me-downs and the equivalent of Sears fashions.

Harajuku in Tokyo is regarded as groubd zero for Japanese street fashion and kawaii culture. It has always been a place where people prefer not to wear the same things as others. Takamasa Sakurai wrote in The Daily Yomiuri, “Views toward young people's fashion are surprisingly conservative in other countries. I talked with a lot of young women in cities like Paris, New York and Milan, and found they don't think their local towns are fashionable. So which place do they think is fashionable? Harajuku.”

In the Los Angeles area you can find girls that wear Japanese-style school girl uniforms and loose socks, Gwen Stephanie used “Harajuku girls” — three Japanese girls in Tokyo street fashions — in her stage show and the video for hit “I Ain’t No Hollaback Girl”.

Fashion Trends in Japan

Important fashion trends over the past couple of decades have included “kawaii” (cute) and “bodikon” (short for body conscious and roughly meaning sexy). Bodikon clothes looked like something a hooker would wear.

Fashion trends that were commonly recognized in 2008 included 1) “akamoji” (“red letter”), style, an elegant, casual style promoted in magazines like CanCam, JJ, ViVi and Ray, which all have covers printed in red; 2) “OL” (“office lady”) style; 3) “mina” (“girly”) style; and 4) street style, with a focus on individuality.

Loic Bizel, a French fashion consultant who operates tours of Japan, told the Daily Yomiuri, “Japanese fashion is very unique in terms of variety” and is a “hobby rather than a fashion or lifestyle...In Europe people are less showy in terms of what they wear because the like to show themselves off through their homes. Japanese people are always outside, so they basically wear what they own so they can show off.”

Kyary Pamyupamyu — New Harajuku Star — and Aomoji-Kei Fashion

Sanae Nokura wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun in June 2011, “One of the latest trends to hit Harajuku's streets is "aomoji-kei" or "blue ink type." A bubbly girl who calls herself Kyary Pamyupamyu is representative of the style. According to Kyary, who recently graduated from high school, aomoji-kei fashion is not tied down to any particular style. "It's fashion enjoyed by people who like Harajuku and come to the area. Aomoji-kei can be very colorful--like what I wear--vintage clothes or Lolita fashion," she explains. [Source: Sanae Nokura, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 3, 2011]

“The style-free aomoji-kei trend is believed to have evolved as a reaction to akamoji-kei (red ink type), a term invented to explain the elegantly casual yet conservative fashion favored by female college students and young office workers. (The titles on magazine covers featuring such fashions are often printed in red.). When asked what aomoji-kei means to her, Kyary says she is a fan of Barbie dolls and '60s fashions.”

“The distinctively dressed 18-year-old was "discovered" on the Harajuku streets when she was 16 and asked to be photographed for a magazine documenting fashion worn in the area. Kyary, whose big eyes and fair skin stand out, began modeling and appeared in magazines such as Zipper and KERA, where editors hoped the girl noted for her peculiar sounding name and sartorial style would identify with readers.”

“The doll-like Tokyo native gradually expanded her activities and is now a regular fixture in magazines and on radio. Despite her busy schedule, Kyary's enthusiasm for fashion is palpable. She often visits her favorite secondhand clothes stores and collects photography books on vintage fashion. Decked out in a short tunic printed with teddy bears and hot pink shorts, her theme when this reporter met with her was "child's pajamas worn in a foreign country." Platform sandals found at a visual-kei boutique completed the picture.”

“Kyary shares her daily style in her blog (http://ameblo.jp/kyarypamyupamyu). "I dress according to my personality. I enjoy dressing for my own pleasure rather than worrying about how I look to others," she says. Her official Web site (http://kyary.asobisystem.com) also introduces fashion items she has produced such as T-shirts, hoodies and false eyelashes.”

Kyary said her dream is to become a "charismatic Harajuku personality." In the summer of 2011, she is expected to debut as a singer. "Harajuku is where fashionable people get together. It's lots of fun. I'm going promote the town and aomoji-kei fashion to the world," she declared, making a weird face for fun.

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, the Singer

Jin Kiyokawa wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Kyary Pamyu Pamyu is a Harajuku fashion icon with a tongue-twister name. She made her debut as a singer in 2011 with a mini-album produced by Yasutaka Nakata, who also produced popular techno pop girl group Perfume. The promotional video for her song "PONPONPON," which is included on the mini-album, has over 17 million views on YouTube. [Source: Jin Kiyokawa, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 2, 2012]

Many overseas fans of the promotional videos have left complimentary comments in English on the website, such as "So cute!" and "I'm obsessed!" Experts point out the video's unique imagery, with floating eyeballs and animated human hearts, was startling to fans. About 6,000 fans attended her concert in Los Angeles in December. Amazed, the pop star recalled, "From the first verse starting with 'Ano Kosatende' (at the intersection), many fans sang the Japanese lyrics to 'PONPONPON' accurately. They even knew and imitated my dance to the song." The promotional video for her single "Tsukematsukeru" has already gotten over nine million views on YouTube this year.

According to Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, the theme for 2012 is "Let's enjoy Japan more," and aims to blend Japanese tradition with current fashion trends. "The trends and designs from the old days are very fashionable. People wore kimono every day and chonmage (topknot) is a novel style. There are many kinds of kanzashi hair sticks and I think these designs can be applied to current fashion," she said.

Kanon Wakeshima

Kanon Wakeshima is a a singer/cellist and Gothic Lolita fashion icon. Stephen Taylor wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Wakeshima's fusion of music genres might not appeal to everyone, yet the results are surprisingly effective, with the shrill cry of J-pop complemented by her subtle cello accompaniment. Wakeshima's debut album, “Shinshoku Dolce” , came out in 2009, with “Shojo Jikake no Libretto: Lolitawork Libretto” released the following year. [Source: Stephen Taylor, Daily Yomiuri, September 16, 2011]

Wakeshima was born in Tokyo in 1988. She has developed a musical style that combines her love of pop tunes with a passion for classical music, the latter a calling that grabbed her from an early age."I started playing the cello when I was 3," Wakeshima said, adding that her bow-wielding future had been determined when she was a mere twinkle in her parents' eyes."My mother and father are big music fans and, even before I was born, they'd decided that if they had a girl, they'd like her to play the cello, because that would be quite cool for a girl," she said.

In primary school, Wakeshima's focus was on classical music, but as her teenage years approached, she was introduced to exciting new sounds. "When I was at middle school, I discovered J-pop and thought, 'Well, what would happen if I applied my musical interpretation to J-pop?' And that's how I've gotten to where I am today," she recalled, adding that at about the same time she also found her look. "I really liked Lolita fashion when I was in middle school, but I didn't have any money so I couldn't buy the clothes. So, when I started high school and got a part-time job, I could save some money and start buying some clothes."

Wakeshima plays a different colored cellos, each with a different name. "The red cello that I used today is called Nanachie...Each of the cellos' names represent numbers in kanji. The brown one that I've been playing since I was at middle school, which I use for recording and rehearsals, is called Yaehauru, while the other ones--the white and the silver ones that are used for live performances and promotional appearances--are named Mikazuki and Momotose, respectively."

Image Sources: Ray Kinnane , Andrew Gray Photosensibility, xorsyst Tokyo Pictures, Goods from Japan; Lolita Fashion, Avante Gauche

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2012