BECKONING CATS AND DARUMA DOLLS

Daruma dolls are red, round dolls named after Daruma (Bodhidarma), the founder of Zen Buddhism. They are commonly sold around New Year with both eyes painted over. One eye is unpainted when making a wish. The second eye is unpainted when the wish comes true.

Daruma dolls have wide open eyes and fierce scowl that are intended to keep evil spirits and demons away and bring good luck. They have no legs because Daruma sat so long in meditation that his legs fell off. Daruma himself is featured in both 15th century paintings and 21st century television cartoons. Daruma dolls with yak hair beards were popular in 2009

“Manekineko” ("the beckoning cat") raises its paw to attract customers and money and brings good luck and wealth. They are seen everywhere and commonly set up outside shops and restaurants. It is not clear where manekineko came from. According to one story they originated with a feudal lord who avoided being caught in a torrential downpour and found refuge in a temple after being beckoned by a cat. In another story the cat raised his paw to protect his owner, a courtesan, from a snake. In any case a raised right paw is supposed to bring money and a raised left paw is supposed to attract customers.

Shoden, or Kangiten, is the Japanese equivalent of the Hindu god Ganesha, usually depicted with the head and trunk of an elephant and the body of a human. Raijin is the Japanese spirit of thunder and lightning. Both feared and revered, he is typically depicted as an oni demons with a set of small devil-like horns and a small, muscular body, holding drumsticks which he uses to pound out thunder on a string of connected drums. Farmers have traditionally venerated him because he is associated with rain while city dwellers, such as those in old Kyoto, feared him because of his association with heavy downpours and floods. In the old days a variety of talisman and spells were sold to ward off lightning strikes. In some places children still cover their belly buttons when they hear thunder to keep Rainjin from stealing them. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri]

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: KI, FENG SHUI AND SHAMANS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; YOKAI, LUCK GODS AND GHOSTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FORTUNETELLERS, BLOOD TYPES AND SUPERSTITIONS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos of Lucky Cats and Daruma at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Yokai Article in Monstropedia monstropedia.org ; Yokai and Kaiden pdf file k-i-a.or.jp/kokusai ; Obakemono obakemono.com ; Tales of Ghostly Japan seekjapan.jp ;Yokai Attack yokaiattack.com ; Anatomy of Japanese Folk Monsters /pinktentacle.com/2009 ; Japanese Ghosts mangajin.com ; Ghosts, Demons and Spirits asianart.com ; Black Moon Japanese Ghost Stories theblackmoon.com/Ghost ; Japanese Legends About Supernatural Sweethearts pitt.edu/~dash/japanlove ; Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de

Folk Religion in Japan Book: Folk Religion in Japan amazon.com ; Folk Beliefs in Modern Japan (1994) kokugakuin.ac.jp ; Japan Times article on Fortunetellers in Japan japantimes.co.jp ; Good Photos of Fortunetellers at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Japanese Fortunetelling on Quirky Japan Blog qjphotos.wordpress.com ; Japanese Fortunetelling on Danny Choo. Com dannychoo.com

Good Websites and Sources on Religion in Japan: A View on Religion in Japan japansociety.org ; Book: Religion in Japan cambridge.org ; Religion and Secular Japan japanesestudies.org.uk ; U.S. State Department 2009 Report on Religious Freedom in Japan unhcr.org/refworld/ ; Resources for East Asian Language and Thought acmuller.net ; Society for the Study of Japanese Religions ssjr.unc.edu ; Contemporary Papers on Japanese Religion kokugakuin.ac.jp ; Japan Glossary Washington State University ; Shinshuren, Federation of New Religious Organizations of Japan shinshuren.or.jp

Animals and Other Lucky Symbols in Japan

Tanukis are Japanese mammals that resemble a cross between a badger and a raccoon. They are regarded as mischievous creatures with high sex drives and magical powers that enable them to change their shape at will. Statues of fat, jolly tanukis holding a bottle of sake are the Japanese equivalent of garden gnomes.

According to folklore tanukis can change their shape and drum their stomach. They appear more often in Japanese legends and fairy tales than almost any other animal. They are often tricksters who play practical jokes and set traps — especially if it helps them get some food — crash parties and drink up all sake and then pay with dry leaves instead of real money. Many stories revolve around battles of wits between tanukis and farmers or are fantastic tales with tanukis changing into monsters or beautiful women.

Dragons and cats are regarded as auspicious. The logo for the Japanese version of the United Parcel Service is a black cat, regarded as protection from evil spirits. White cats are supposed to bearers of good luck. Red cats ward off evil. Frogs represent a “safe return.”

Carps are a popular Japanese symbol. They are admired for their strength and determination to swim upstream, traits that parents want their children to have. On the holiday of Children's Day, paper carp wind banners are hung from poles at Shinto shrines, homes and other places and hung in lines across rivers near bridges.

Cranes are symbol of peace and hope. A folded paper origami crane, a symbol of healing, is often given to someone or placed somewhere as a goodwill gesture. It is said that if you fold 1,000 cranes your dream will come true.

Turtles are symbols of longevity. In some places if you see a spider in the morning it brings good luck. In other places a spider seen at night brings good luck. “Hatsuyume”, the first dream of the year, is important. Dreaming about hawks, Mt. Fuji or eggplants is supposed to bring good luck.

Bad luck symbols include monkeys (“saru”, which can also mean “customers leaving”) and sunsets and anything red (“akaji”, meaning “in the red” and things falling). Rice has religious significance . Mochi (a soft rice cake) is considered a symbol of happiness. It is eaten at festivals, weddings, ceremonies for new houses and other occasions.

See China, Religion, Superstitions

Foxes, Religion and Folklore

a fox In Japanese folklore foxes are regarded as clever and magical animal who act messengers for the gods, particularly the God of the Harvest, and are symbols of fertility. Killing one sometimes results in punishment by the gods. Small shrines for rice and harvest gods are found at Shinto shrines and some Buddhist temples. They are invariably guarded by foxes. Foxes are believed to have the power to change their forms, possess humans and cause people to have hallucinations so they can trick them. Their favorite entry point is under the fingernails. Their favorite food is said to be deep-fried tofu, which is often found in shrines next to fox statues.

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Foxes are among the great perennial stars of Japanese folklore. To begin with, they are considered to be familiar spirits serving the immensely popular rice deity Inari. A set of two stone foxes stand watch in front of every Inari shrine. Some folklorists believe that foxes became associated with rice farming because of their role in controlling mice, hares and other agricultural pests. In the past farmers would even leave out food to attract foxes to their rice paddies. Foxes are thought to be especially fond of abura-age, thin slices of deep-fried tofu soy bean paste. Pockets of abura-age stuffed with rice are known as Inari-zushi. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, May 10, 2012]

“Yo-gitsune is the Japanese word for fairy foxes. “In contrast to the favorable agricultural image, foxes have also been traditionally imagined as clever tricksters and shape-shifters. These yo-gitsune can be encountered in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Like cats and many other Japanese fairy animals, their magical powers grow stronger with age. After living for a century or two, yo-gitsune become able to possess people, causing illness or insanity, and also to temporarily shape-shift into incredibly glamorous women. Stories abound of men falling hopelessly in love with and marrying these "foxy ladies.”

“In one famous story, a 10th-century nobleman saves a fox from a mob bent on killing it for its liver. A few days later, a beautiful woman mysteriously appears at his door. They fall madly in love, get married and have a son. Three years later, the woman suddenly disappears, leaving a note explaining to her husband that she was really just the fox whose life he had saved. Their son grows up to be Abe no Seimei, the famous Onmyoji Yin-Yang wizard who protects the imperial court and the capital city from all sorts of wicked spells and disasters.

“After living for a full millennium, fairy foxes may attain a formidable style with nine tails. Nine-tail foxes, or Kyubi no Kitsune, are of Chinese origin, but have also been active in Japan as well. During the Edo period (1603-1867), motifs depicting heroes ridding the land of these often ill-tempered nine-tail foxes were widely adopted into traditional theater, literature and art.

“Until quite recently, mental illnesses and emotional instability were frequently attributed to possession by fox spirits, especially in isolated rural villages. Even more frightening, there are families, called tsukimono-mochi, which are rumored to keep tiny fox spirits in vases or bamboo tubes. These spirits can be sent out on various missions, such as searching for gold or treasure, stealing, spying on people, or just causing all sorts of trouble and misfortune. The secrets of caring for and controlling these fox spirits, or in some cases similar dog or weasel spirits, are passed down from generation to generation among women of the household. Families which are rumored to possess fox spirits are feared and shunned.

“Another peculiarity of fairy foxes is that they tend to emit strange lights at night. One very famous spot for kitsune-bi fox-fire is the Inari shrine at Oji in Kita Ward, Tokyo. Every New Year's Eve foxes from all over the Kanto region are believed to assemble here under an ancient hackberry tree. The local farmers predict the yields of the coming season's crops by the number of glowing lights they count.

Inari shrines for foxes are very common. Some have thousands of images of foxes. These places are thought be haunted and best avoided after dark.

Snakes Considered Mystic Messengers of Japanese Water Spirits

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “In addition to being one of the 12 animals of the traditional Asian almanac, snakes are widely revered as messengers and familiars of local deities. Here in Japan, they are primarily associated with water spirits. A good place to look for spiritual snakes is at tame-ike irrigation ponds. In the Kanto region, these are usually formed by damming the upper reaches of a narrow valley, at a spot where water naturally springs or seeps from the surrounding slopes. The water is held in the pond, then directed downstream though a series of canals and ditches to the waiting rice paddies. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, January 3, 2013]

Japanese civilization was built on irrigated rice cultivation, and securing a sufficient source of water has always been the key to successful farming. Naturally, the Japanese, as did people in most of the world, place a high cultural value on spots that form their major source of water. Tame-ike irrigation ponds have traditionally been treated as sacred places, inhabited and protected by spirits known generically as Suijin (literally water deities).

Suijin are typically revered in shrines constructed on small islands in the pond, or at least on chunks of land jutting out from the shore. A good example of this arrangement can be seen at Shinobazu Pond in Ueno Park. The Suijin enshrined here is an extremely popular Buddhist deity known as Benzaiten. Benzaiten is sometimes depicted with a coiled snake sitting on top of her head. In rare instances she also appears in a very special avatar, with the body of a coiled snake and the head of a human being. This avatar is known as Jatai-Benzai, or "Snake-body Benzai." A closely related Suijin, also often revered at irrigation ponds, is called Ugajin.

Snake-body Suijin are rare, but you can see a stone statue of Ugajin just above the pond at Inokashira-koen park in western Tokyo. At one tiny irrigation pond in the Saitama countryside, I discovered a wonderful statue of a snake-body Benzaiten, only about a half-meter high, along with a tile plaque depicting a snake that serves as her familiar. In this case, the sculptor went through considerable effort to depict a real snake. The short but thick body, fat head with puffed cheeks holding the poison glands, and mottled markings are clearly those of a mamushi pit viper!

Seven Gods of Good Luck

Japan’s Seven Gods of Good Luck

“Shickifuku-jin” are the seven gods of good luck. First used by merchants in Kyoto and Osaka in the 15th and 16th centuries, they are often pictured on a treasure ship and are popular New Year's images. Praying to them, having their images around or making pilgrimages to places associated with them is supposed to bring happiness and good fortune. The power of two or more of the gods working together far exceeds the of the power of each one acting on their own, with the power of all seven working together having the greatest power of all.

The seven gods of good luck are: Ebisu, Daikokuten, Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Hoeti, Furkokokuju and Jurojin. Of the seven Ebisu is the only one that originated in Japan. Daikokuten, Bishamonten and Benzaiten come from India and Hoeto, Furkokokuju and Jurojin come from China.

Outside a famous temple in Kyoto there is a machine from which people can buy charms related to the seven deities of good fortune. The charms bear codes that charm-owners can access online or with their cell phones to get to a fortune-telling website. The concept was developed by Fujitsu and a Kyoto-based wedding kimono manufacturer.

See Separate Article: BUDDHIST GODS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Rice Paddy Spirits

Ta no Kami is the Japanese word for rice paddy spirits. Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The Ta no Kami cult is widespread throughout the country, and is at the heart of Japanese rural folk cosmology. The Japanese imbue rice with a sacred reverence and deep cultural significance that completely transcends the plant's nutritional and economic value as a food grain. It was rice, first brought here from the Korean Peninsula nearly 3,000 years ago, that transformed Japan from a land of scattered hunter-gatherers to a great nation. Gohan, the basic word for cooked rice, is also a general term for food or a meal. Even today, the Japanese people, despite their insatiable appetite for bread and noodles, still think of themselves as rice eaters. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, April 19, 2012]

“In most regions, the Ta no Kami are represented abstractly, with tree branches decorated with strips of paper, sometimes stuck into mounds of sand. In a restricted area of southern Kyushu, however, there is a tradition, dating back to at least the early 18th century, of carving unique stone representations, locally called Ta no Kansa. This tradition centers in Kagoshima Prefecture but includes a small portion of neighboring Miyazaki Prefecture as well.

“The statues here are very typical of this Kyushu style. Each wears around his head a thick cowl that is actually the prop in a clever illusion. Seen from behind, this cowl turns into the top of a potent male phallic symbol. In Japanese folk cosmology, the rice-paddy spirits are actually one and the same with the Yama no Kami, or mountain spirits, which are sometimes represented as phallic symbols.

“Yama no Kami reside in hills and forests all over Japan. They can be thought of as basic animistic spirits mingled with the departed souls of the local ancestors, which are believed to eventually rise into the mountains. In many regions, these basic protective spirits inhabit the mountains during the winter months, but come spring they move down into the rice paddies, turning into the Ta no Kami and watching over the precious crop until the autumn harvest is over, after which they return to the forested slopes. In Kyushu, the Ta no Kansa stones are placed on the dikes that surround and separate the paddies, and the villagers hold colorful festivals to welcome and petition the Ta no Kami in spring, and to see them off with great thanks in autumn.

Yokai

“Yokai” is a Japanese word for Japanese supernatural beings. Sawa Kurotani, a professor of Anthropology at Redlands University, wrote in the Daily Yomiuri. “Yokai are unique products of Japanese supernatural beliefs, with no exact equivalence in Western culture. They stem from the animistic world view of Shinto, in which everything animate and inanimate has a spirit, and therefore has potential to turn into supernatural beings with mystical powers. Their shapes and characters vary widely; so do their powers and capabilities.”

“While origins and shapes vary greatly," Kurotani wrote, "all yokai have one thing in common: they are the products of “blockage” — pent-up emotions that can not be expressed, desires unfulfilled, lives terminated prematurely, inanimate objects that cannot fully turn into divine beings. They are condemned in perpetual limbo, between being and becoming, in neither this world nor the nether world. This perpetual in-between-ness is the source of their strangeness and grotesqueness.”

The Japanese have traditionally been fascinated with yokai, and other spirits such as “mononoke” and “ayakashi”, and many believe they truly exist. Rather than view them as something scary or horrible they are seen as things that exist in everyday life and have to be dealt with. In the Heian period (794-1185) the Emperor employed an “onmyoji”, a bureaucrat who handled all supernatural matters connected with Imperial Court.

Records of yokai exist in Japan’s earliest historical documents. “Gazu Hyakki Yako” (“Illustrated Fairy Night Parade”) was landmark publication released in 1776 with detailed research and illustrations of more than 100 yokai species. In other publications descriptions of yokai often appeared side by side with descriptions of real plants and animals, with some like tanukis and foxes, having both yokai and biological descriptions.

Book: “Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide” by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt (Kodansha International, 2008) is a field guide to 122 Japanese monsters. “ Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai “ (University of California Press, 2009) by Michael Dylan Foster, a professor at Indiana University; “ Anime and Its Roots in Early Japanese Monster Art “ by Zilia Papp, professor at Hosei University (Global Oriental, 2009) Papp traces the visual genealogies of many of yokai with an 18th-century yokai catalog by Toriyama Sekien.

Yokai and the Modern World

tengu Yokai were dealt a serious blow by modernization, Westernization and industrialization but they seem to have made a comeback in recent years thanks to books, mangas anime and films that feature them. Many non-Japanese have been exposed to them in Miyakazai films such as “Princess Mononoke” and “Spirited Away”.

Manga expert Ryota Fujitsu said Japanese secretly believe in yokai despite being surrounded by a modern technological society, “When something strange happened in your room — your brand-new computer suddenly stops working and then starts up again just as suddenly — it — ll make your life more interesting if you believe it’s the doing of a yokai.”

A test of people’s knowledge of yokai is offered in Tokyo. According to old folk tales you are most likely to encounter yokai in the twlight hours around sunset.

Some explain the recent fascination with yokai to a pursuit for explanations that defy the logic of the modern world brought about the hard times that people are experiencing in their on lives a result of economic hardships. Others link it with Shinto are traditional animist beliefs that local spirits are everywhere: in forests, in mountains, in ponds, rivers, trees and rocks.

Different Kinds of Yokai

“The long-nosed tengu glares at a solitary traveler from the branches of a tree. Below the mountain, a web-fingered kappa lurks in the dark water beneath a bridge. Downstream, there's a rustling sound in a garbage dump as discarded items eerily come to life as tsukumogami. And on city streets, a seemingly ordinary woman known as Kuchisake Onna uses a cold-sufferer's sanitary mask to hide a gaping mouth full of sharp teeth... Each of these entities is a yokai.[Source: Tom Baker, Daily Yomiuri, December 2010]

Tools and household items such as umbrellas, inkstones and pots are said to turn into yokai after 100 years of age. Many yokai have regional associations. The “nureonna” (“wet woman”), a grotesque creature with the head and arms of a woman and the body of a giant snake, inhabits dense willow forests along the banks of swift-flowing rivers in the deep mountains along the borders of Fukushima and Niigata Prefectures in northern Honshu.

Among the yokai associated with Yokkaichi, a town on Ise Bay, are the Nure Onna, who has the upper body of a hag and the lower body of a colossal snake, and Kara Kasa, a one-eyed umbrella that hops about on a single leg. The mountains of northwestern Shikoku are said to be the home of a huge fire-breathing bird called the Basan. It has been described as a nocturnal creature with beak, fleshy wattle and spurs on the back of its legs sort of like those on a rooster.

There are also yokai that seem to have a relatively recent origin. Foster writes that "some Japanese scholars have suggested the Kuchisake Onna, for example, “may represent a sort of education mama turned monster: the image of her confronting children...on the twilit streets between school and supplementary lessons at juku, was born of anxiety felt by children about pressures exerted by their own mothers." Award-winning Canadian comic book artist Nina Matsumoto told the Daily Yomiuri Shimbun she thinks the Kuchisake Onna is "something adults can use to scare children. It's a very useful urban myth. 'Children, don't stray too far, or go with strangers.'" [Source: Tom Baker, Daily Yomiuri, December 2010]

On the psychological origin of another yokai, the Konaki Jiji — a baby who changes into an old man who drags you down, who crushes you to death — fiction writer John Paul Catton, told the Daily Yomiuri; "To me it represents the fear of responsibility and the fear of parental obligations which you can't keep, which turn into a millstone around your neck. And this is a literal example of that."

Japanese Mythical Creatures

Japanese have believed for a long time that certain animals and monsters, known collectively as “bakemono”, possess supernatural powers to resist diseases and illnesses and ward off curses. These include the “kudan”, a creature with a cow's body and a human face; and the “tsuchinoko”, a snakelike monster first described in the 8th century that has a thick body, stubby tail and squeaks like a mouse.

The Japanese version of the boogie man is called the “namahage”. On certain holidays men is namahage costumes (a demonic mask and a haystack-like cloak) go door to door to discipline children who have been naughty. Children usually hide when the demon comes and parents appease him and get him to leave with an offering of rice cakes. "When I was a young boy," one man told National Geographic, "I was very scared of the namahage. I wouldn't even tell my parents where I was going to hide."

The Japanese have also traditionally believed to be in a wide range of ogres, demons, goblins, dragons, “raiju” (beasts that fall from the sky during thunder storms), “nekomata” (old cats that have turned into monsters), mermaids and mermen. Not all supernatural creatures are bad. Akihara is a protector spirit created by the merging of pious monk and the place where the monk meditated for 1,000 days.

Tengu

“Tengu” are troll-like creatures infamous for their unpredictable nature and habit of both kidnaping unsuspecting children and returning missing ones. Associated with mountainous areas, they have long phallic noses, wings and are typically found riding on the back of white foxes. Tengu are part bird and part human. They reside deep in the mountains and come in two types: large ones with a long nose and smaller ones with a bird’s beak nose. The larger type is often depicted carrying a magic fan of bird feathers.

Kevin Short, a cultural anthropologist at the Tokyo University of Information Science, wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “ Tengu originated in China, and were conceived of as spirits of shooting stars. Their appearance was considered unlucky, a portent of disasters and misfortunes to come. The first one recorded here in Japan was in the early eight century. Once here, however, the tengu began evolving in their own directions. They quickly became associated with mountain ascetics, called yamabushi or shugengja.”

“Tengu are adept at shape-shifting , able to turn into a bird of prey such as a kestrel or black kite, and also to take on the form of a human being at will. They are absolute experts at conjuring up visions, which they can use to trick Buddhist monks and other susceptible people . Although basically devious and mischievous in nature, when tengu take a liking to someone they will reveal secrets of invisibility or invincible swordplay.”

“The big tengu’s magic fan can be used for various purposes. When angered they can fan up a great storm or whirlwind. Many charming folk stories also attribute to them the ability to make a person’s nose grow or shrink. Often a thief or mischievous boy steals the fan, after which his nose grows way up into the clouds, where it gets stuck, When the miscreant tries to retrieve his nose by shrinking back to normal size, he is pulled up into clouds instead, never to be seen again.”

“By the 17th and 18th centuries, Japan’s tengu population was recorded to have risen to 125,000. Of these, however, only 48 were of the large long-nosed variety, the vast majority being the smaller beak-nose type. The large tengu all have proper names, and most are associated with a single mountain although they are known to sometimes move around or exchange abodes.”

Mountains around the Kyoto plain such as Mt, Hiei and Mt. Atago and those around Tokyo and the Kanto Plain such Hakone and Mt. Takeo are said to be home to many tengu. The tengu on Mt. Akiha in Shizuoka Prefecture is said to have been a former yamabushi who spent 1,000 days training in the high mountains and discovered a variety of secrets and now rides aorund on a pure white fox and is revered for his ability to prevent fires.

Kappa

a kappa The “kappa” is an amphibious, web-footed aquatic creature, about the size of an 11-year-old boy, with a sharp beak for a mouth and bald patches on the tops of it head. Kappas are known for tripping up horses and stealing vegetables from fields, and using their anus to cause various forms of mischief. Children are told not to swim too far out in rivers or the kappa will pull them under and suck the life energy out of them. Kappas receive their power from a depression in their head that holds water. The easiest way to trip one up is to bow. When the kappa returns the bow, water spills from its head and it loses its powers.

Kappa is the name of a popular sportswear company in Japan. Ceramic versions of kappa are fixtures of gardens and the equivalent of garden gnomes. Even though kappas stories vary a lot from region to region they usually describe how the kappa cleaned up his act after performing some act of mischief. Popular ones include “The Kappa Who Became Angry While the Pond was Filling Up, Kappa’s Bond” and “Kappa’s Pledge in a Letter”.

Evidence of Mythical Creatures in Japan

a Japanese merman mummy

displayed at the British Museum Until about 100 years ago Japanese believed that kappa and tengu inhabited the forest and rivers of Japan. A tengu mummy is kept in Hachonoche, Aomori Prefecture. One temple has an entire hand of a kappa. A bakemono claw is displayed at another temple. Analysis of the tengu mummy reveals it has the head of a cat and the legs, wings and feathers of a woodcock.

In his 2009 book “ Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai “ Indiana University Prof. Michael Dylan Foster writes that questions about what yokai are"often elicits not a definition, but a list of examples." The earliest references to yokai, he said, are records nearly a thousand years old that describe to a "night procession of 100 demons” said to be so terrifying viewing it could fatal. [Source: Tom Baker, Daily Yomiuri, December 2010]

Mummified ogres, and mermen have been displayed at Japanese museums and temples. A temple in Shizuoka claims to possess a letter of apology written by a tengu captured by the temple’s head monk in the mid-17th century. In 2001, a “tsuchinoko” was found and displayed in the small ski resort of Mikata.

Historians have found papers with special medicines and prescriptions "administered by kappa." A number of encounters with supernatural creatures have been reported. A document dated to 1853 described the death of 13 samurai officials by a five-meter-long monster, with a body like a seal and the face of a monkey, disturbed in a canal near Inba Marsh in Chiba Prefecture.

Many creatures were displayed at a exhibit at the Kawasaki Museum called “Japan’s Mythical Creatures: Accounts of Unidentified Living Organisms”. DNA analysis of some of the creatures revealed that many were made by combing monkey remains with body parts from other animals.

A temple in Kamuro in Hashimoto in Wakayama Prefecture contains a mummified mermaid that looks like the head from Munch’s “The Scream” attached to the body of a fish, and most likely is the body of fish sewn onto the head of a snow monkey whose face has been reconstructed. The mermaid is thought to date to the early- or mid-19th and perhaps was used in a traveling freak show.

Lake Kussharo in Hokkaido is said to be the home of Lochness-like monster named "Kussie." Since 1973, more than 100 local people in the town of Teshikga have reported seeing the long black eel-like creature.

Nostradamas and Japan

In a 1999 survey, 20 percent of Japanese said they believed in doomsday predictions of Nostradamas, including the prophecy that a "King of Terror" would occur in July 1999.

As the year 1999, approached the sales of Nostradamas books skyrocketed and Nostradamas experts appeared on television (one claimed he could speak Venusian). Some people built $80,000 bomb shelters or packed away a tent, water purifier and survival guide in anticipation of impending doom.

One of the motivations behind the March 1995 sarin gas attack at the Tokyo subway was to provide a confirmation for the Aum cult's belief in Nostradamas prediction that the world was going to end.

The Japanese Nostradamas phenomena dates back to the 1960s, when a journalist named Ben Goto wrote a series of bestselling books that interpreted Nostradamas's predictions in a Japanese light. Afterward when big things happened — like the Kobe earthquake, the launch of missiles by North Korea — they were given a Nostradamas spin and offered as proof of his predictions.

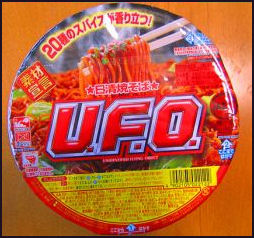

UFOs and Japan

UFO instant noodles About one forth of the UFO sightings in the developed world occur in Japan. Arakawa, a famous Japanese doomsday survivalist, claims she was given important information from aliens she met.

In December 2007, a high-level government panel took up the topic of UFOs and issued a report, stating that it had no officials plans in the case a UFO landed in Japan and said it had not confirmed whether UFOs were piloted by space aliens, It was the first time the government had taken an official position on UFOs. The discussions began when a lawmaker submitted a written question to the cabinet, asking whether the government could conform that UFOs were alien spacecraft.

Discussions on the UFO topic went on for so long that a lawmaker nicknamed “Alien” Secretary General Yukio Hatoyama—who became the Prime Minister of Japan — called for UFO discussions to stop, saying “If aliens existed and came to Earth, they would have to be creatures of far greater intelligence than human beings, which is just impossible. Since it’s all completely fantasy, it makes mo sense to discuss how the Defense Ministry will respond.”

A series of lectures “ called “renewed Spectrology” on ghosts, demons and UFOs using philosophical, psychological and religious approaches to analyze them is among the most popular courses at Toyo University.

Image Sources: 1) cat, fox, daruma dolls, Goods from Japan, 2) Seven gods drawings, yokai JNTO3) 4) seven gods photo, Ray Kinnane, 5) ghost, merman and skeleton ukiyo-e, British Museum, 6) cosplay ghost Andrew Gray, Photosensibility7) UFO noodles exorsystblog

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024