SHAMAN IN JAPAN

Itako shaman There are still shaman in Japan but they are not as big as they are in Korea. Shaman are people who have visions and perform various deeds while in a trance and are believed to have the power to control spirits in the body and leave everyday existence and travel or fly to other worlds. The word Shaman means "agitated or frenzied person" in the language of the Manchu-Tungus nomads of Siberia.

Shaman are viewed as bridges between their communities and the spiritual world. During their trances, which are usually induced in some kind of ritual, shaman seek the help of spirits to do things like cure illnesses, bring about good weather, predict the future, or communicate with deceased ancestors.

Shaman are generally poor and come from the lower social classes. Sometimes their spiritual power is seen as so great that they need to be separated from society. In the past, it is believed, almost all villages had a shaman and they were members of a caste that passed their traditions down from generation to generation. Some shaman are afraid to reveal their secrets because they believe that after they pass on their secrets they will die.

Shaman can be both men and women. Many are women. Traditionally, they have not chosen to become shaman but rather had shamanism thrust upon them. The process of becoming a shaman usually follows five steps: 1) a break with life as usual; 2) a journey to an "other world;" 3) dying and being reborn: 4) gaining a new vision: 5) and emerging with a deep sense of connectedness and purpose.

See Separate Article ANIMISM AND SHAMANISM factsanddetails.com

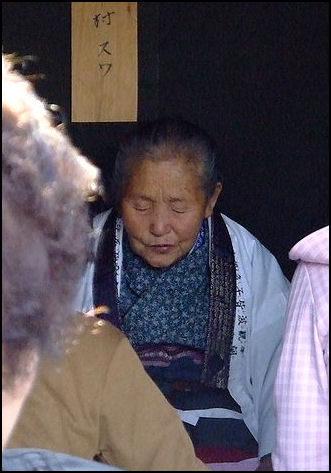

Itako Shaman

“Itako” are shaman or mediums that have traditionally been blind or sight impaired old women that were called upon by bereaved family members to communicate with the dead. They embrace folk religion and animist traditions but also call upon Buddhist and Shinto gods for help. Each itako has her own gods that she calls upon. Some use aids such as beads and stringed bows to call the gods.

Itako have traditionally been looked down upon as little more than beggars. They were persecuted in the Meiji period and they sought refuge in remote places. They often dress in ragged clothes. When other people saw them they threw horse dung at them.

Itako were once common throughout Japan. According to one researcher there may have been 1 million of them roaming the countryside, working as mediums and healers, 150 years ago. They usually traveled with “yamabushi” (See Buddhism). Only about 20 or so itako remain, they are mostly in Aomori.

“Onmyoji” are traditional shaman trained in Taoist, Buddhist and Shinto magic. They are sometimes called on to perform exorcisms, which are done by convincing the spirits they should leave rather than forcing them out.

Book: “Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan” by Carmen Blacker (Japan Library, 1999). The name of the book refers to a single string instruments used by Japanese diviners to communicate with the spiritual world.

Itako Shaman in Aomori

Entsuji, a Buddhist temple near a crater lake in Osorezan, a composite volcano in the middle of Shimokita Peninsula in Aomori Prefecture in northern Japan, hosts a four-day festival in late July that features itako who communicate with the dead.

During the festival the women sit in blue tents and people who want to communicate with dead loved ones form lines to meet with the old women, who charge ¥3,000 per spirit per 30 minute session. Some work at shrines and others work at their homes outside the festival times. Some moonlight as fortunetellers.

Itako Initiation in Aomori

Itako shaman One itako told the Daily Yomiuri that when she was a child her poor eyesight kept her from attending school and “people thought I was strange because I said strange things.” She started to became aware of her itako powers when she discovered she could predict future events, such as natural disasters and accidents that would affect people and was able to find things people lost.

Itako train as an apprentice for five to seven years and then go through an initiation and series of tough endurance tests. The itako above began learning scripture by ear when she was a teenager from an itako master and stopped eating meat and eggs. She became an itako at the age of 18.

Kokhan Sasaki, a professor at Komazawa University, told the Daily Yomiuri that itako dress for 100 days in white kimono before their initiation ceremony and stop eating grain, salt and avoid artificial heat. As part of their training they pour cold water on themselves in the middle of the winter and memorize scripture, a time-consuming task especially when considering they have difficulty seeing.

During the ceremony itself an itako initiate dresses as a bride and is married to a god in a ceremony that involves chanting to bells and drums, whose sounds induces a trance, Sometimes it takes a long time for the initiate to go into a trance. When she does, the master itako that is present determines which gods has possessed her. During the whole process the new itako is not allowed sleep and is only given minimal amounts of food.

Itako Seances

During a seance with an itako known as “Kuchiyose”, the itako receives the death date of deceased person and it relation to the customer. She than rattles prayer beads, goes into a trance and sings to call the spirit to possess her. The spirit usually thanks the petitioner, wishes good fortune and life and discusses personal matters.

Itako usually claim they don't know what is said while they are in a trance. They say that while they are in a trance it feels like they have been grabbed by a powerful force and moved to someplace where they can watch themselves.

The seances last about 10 minutes. Through the medium, the spirit usually says something like, "I am very sorry for having died before my parents, but I am glad that you have come here. I am OK, and hope you are too."

Describing Japan’s only male itako, Miki Fuji wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “I ask Narumi to contact my grandmother. He closes his eyes and begins to chant Buddhist scriptures while rubbing black beads in his hands, until his speech suddenly becomes addressed to me...”I rest peacefully on a lotus with grandfather. Your mother may become ill in December and this may develop into pneumonia if she doesn’t take care. But it won’t be serious if she takes precautions early enough.”

Doctors are studying subjects who have participated in Kuchiyose to see if they have had a healing effect from the ritual. In survey of 670 people with chronic diseases in the Aomori area, 35 percent of them said they had taken part in a Kuchiyose ritual. Of those 80 percent said the experience was beneficial. Thirty percent said they felt mentally healed and 27 percent said they felt calm after speaking to the shamans. One doctor involved in the research told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Kuchiyose has an effect of giving people a sense of comfort and encouragement to live thinking about the future.”

Itako, Feminism and Trances

Kohkan Sasaki, professor emeritus of Komazawa University is a researcher of religious anthropology who has studied shamanism in Asia., told the Daily Yomiuri: “While male shamans are common in China and Southeast Asia, female shamans are more prevalent in India, North and South Korea, and Japan, where societies are based on patriarchal values. I think shamans tend to be female in societies where women are suppressed or discriminated against as an inferior gender. By associating themselves with the gods, women are able to balance their power with men in such societies. Japanese used to believe that the gods offered mercy to those in misery, especially Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. She is one of the most commonly believed-in gods among itako. I have seen noseless yuta shamans in Okinawa Prefecture. Such physical defects used to be interpreted as symbolic of supernatural stigmata. The oldest reference to female shamans in Japan appears in the Wei Zhi, a Chinese chronicle of the third century. A woman called Himiko, who is described as a shaman, ruled an early Japanese political federation known as Yamatai using a divine power to converse with the gods.The first reference to female shamans in Japanese writing dates back to the 11th century. [Source: Miki Fujii, Daily Yomiuri]

On the religious beliefs of itako, Sasaki said: “Shamanism is based on animistic folk religions. In the case of itako, they believe in a number of gods from various different beliefs, such as animism, Buddhism and Shinto. Rather than simply mixing these beliefs, they superimpose later religions on top of existing ones, enabling long-running beliefs and gods to maintain strong identities. During an initiation ceremony, each itako will come into contact with the gods that will possess them. They will also learn which god is most powerful in a variety of different circumstances.

On the itako initiation ceremony Sasaki said: “In training for initiation, itako dress in a white kimono 100 days before the ceremony. They pour cold water over themselves from a well, river or pond--usually this takes place in midwinter--and practice chanting. Three weeks before the ceremony they stop taking grain, salt, and avoid artificial heat. This helps to create an extreme state of mind to facilitate their entering a trance. During the ceremony itself, the itako trainee is dressed as a bride to indicate that she will marry a god. Repetitive drum and bell sounds are produced to help raise concentration levels and prepare the mind while older itako sit around to assist the chanting. The session can continue for days and days until the itako finally enters a trance. That is when the master itako determines which god has possessed the trainee itako. During this tough ritual trainees are not allowed to sleep and their consumption of food is kept to a minimum. Because many itako suffer from some kind of visual impairment, trainees must learn by heart various scriptures. In this way, some itako know the scriptures better than some of the less-motivated priests.

On why itako have not garnered the same respect as priests, Sasaki said: The difference between priests and shamans lies in the fact that shamans go into a trance while priests simply ask the gods for mercy. Priests often come from privileged backgrounds while shamans are generally lower-class people or social outcasts. Before Buddhism and Confucianism entered Japan, various emperors made use of the services of shamans. But as doctrinal religions were introduced, animism became vilified as the superstition and heresy of primitive culture. A similar trend can be seen in most civilizations around the world, in which folk religions are eliminated by institutional religions such as Buddhism, Christianity or Islam. Eventually, the religious rituals once performed by female shamans in Japan in ancient times were taken over by men of later, more sophisticated religions.

On How can you verify that an itako has really entered a trance, Sasaki said: “Although this is a crucial point for researchers, you can never be sure that a trance is entirely authentic. I think the important point is that the client believes in the power of the itako and that society accepts the tradition. This is one aspect common in all religions.

On How shamanism can help make up for weaknesses of modern culture, Sasaki said it can provide relief for people in extreme suffering and pain, making fuller use of people's daily lives and keeping society and culture intact. Shamanism fills some of the spaces left open by modern rationalism and science.

Small Town Shaman Fire Ceremony for a Mountain God

Describing s small town shaman fire ceremony in the Kiso area between Nagoya and Nagano, Thomas Swick wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Mr. Ando, the man in the brown cardigan, invited us to a goma (fire) ceremony that evening at his shrine...Mr. Ando was a shaman in a religion that worships the god of Mount Ontake. [Source: Thomas Swick, Smithsonian magazine, October 2010]

That evening “about a dozen similarly garbed celebrants sat cross-legged on pillows before a platform with an open pit in the middle. Behind the pit stood a large wooden statue of Fudo Myo-o, the fanged Wisdom King, who holds a rope in his left hand (for tying up your emotions) and a sword in his right (for cutting through your ignorance). He appeared here as a manifestation of the god of Mount Ontake.

“A priest led everyone in a long series of chants to bring the spirit of the god down from the mountain. Then an assistant placed blocks of wood in the pit and set them ablaze. The people seated around the fire continued chanting as the flames grew, raising their voices in a seemingly agitated state and cutting the air with their hands in motions that seemed mostly arbitrary to me. But Bill told me later that these mudras, as the gestures are called, actually correspond to certain mantras.”

“Each of us was handed a cedar stick to touch to aching body parts, in the belief that the pain would transfer to the wood. One by one, people came up, knelt before the fire and fed it their sticks. The priest took his wand — which, with its bouquet of folded paper, resembled a white feather duster — and touched it to the flames. Then he tapped each supplicant several times with the paper, front and back. Flying sparks accompanied each cleansing. Bill, a Buddhist, went up for a hit.”

Image Sources: Wikipedia and UNESCO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013