SUPERSTITIONS IN JAPAN

erect chop sticks in rice

are bad luck in Japan

because that is the way rice

is given to the dead The Japanese are very superstitious. Many businesses have shrines; farmers offer sake to the rice field gods before planting their crops; and new cars and Japanese-American FS-X fighter planes are sometimes exorcized of demons by sacred-branch-waving Shinto priests. Fortunetellers — who use Chinese astrology, palm reading, feng shui and name analysis — are consulted by prospective brides selecting an ideal marriage partners, supervisors making promotion and hiring choices, corporate presidents making important decisions, and store and restaurant owners picking names of their business, the most auspicious time to open, and the best floor plan and orientation of the rooms.

A survey by the Yomiuri Shimbun revealed that 56 percent of Japanese said they had some form of supernatural experience. Another survey found that half of Japanese students interviewed said they believed in telepathy, reincarnation and "after-death worlds." Japanese are also fascinated by ESP, UFOs, and ghosts. Japanese television is filled with shows about ghosts and supernatural occurrences.

Traditionally, Japanese have believed that pots and pans, tools and musical instruments gained a soul through repeated use. Japanese are sometimes reluctant to buy used items. Explaining why, one Buddhist monk told the Japan Times, "We are worried about the spirit in things. Depending on the history of the object, it could bring bad luck."

In Japan it is said to be bad luck to blow a flute at night because the sound may attract snakes.

Research by social psychologists Rees Lewis and Helga Dittmar suggests that Japanese attachments to amulets cab be explained in terms of a “magico-religious” function of “cognitive-affective” function (a reference to role in invoking memories and mediating emotions) and the attachments itself was not strong in that amulet owners didn’t seem that upset if their amulets were lost. Consumerism also plays a role. Amulet vendors say that costumers often chose amulets based on color and price. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

A survey by religion scholar Eugene Swanger in the 1980s found 15 kinds of “ omamori “ in six categories at Asakusa shrine in Tokyo and 77 types covering 45 needs, including success in an election, protecting a ship’s engine and preventing water pollution, at Kompira shrine in Shikoku. Aso Shrine in Kyushu conducted annual survey to assess which needs needed to be addressed [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

Websites and Resources

fortuneteller Links in this Website: KI, FENG SHUI AND SHAMANS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; YOKAI, LUCK GODS AND GHOSTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FORTUNETELLERS, BLOOD TYPES AND SUPERSTITIONS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Superstitions, Nihon Sun nihonsun.com ; Japanese Superstitions, Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; Wikipedia on Japanese Superstitions Wikipedia ;Japan Visitor on Blood Types japanvisitor.com ; Blood Types and Personality issendai.com ; Academic Paper on Blood Types and Personality sciencedirect.com

Folk Religion in Japan Book: Folk Religion in Japan amazon.com ; Folk Beliefs in Modern Japan (1994) kokugakuin.ac.jp ; Japan Times article on Fortunetellers in Japan japantimes.co.jp ; Good Photos of Fortunetellers at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Japanese Fortunetelling on Quirky Japan Blog qjphotos.wordpress.com ; Japanese Fortunetelling on Danny Choo. Com dannychoo.com ;

Chinese Calendar, Zodiac and Astrology PaulNoll.com ; Mathematics of Chinese Calendar math.nus.edu ; Wikipedia article on Chinese Calendar Wikipedia Chinese Astrology 12 Zodiac 12zodiac.com ; Chinatown Connection on Astrology Chinatown Connection ; Chinatown Connection on the China Zodiac Chinatown Connection : Wikipedia article on Chinese Astrology Wikipedia

Chinese Astrology and Birth-Year Animals

The Chinese Zodiac , which is used Japan, is based on years rather months. Each year in a 12-year cycle is named after a different animal, with distinct characteristics associated with that animal. Many Japanese believe that the year of a person's birth is the primary factor in determining a person's personality traits, mental and physical attributes and success in love and life. In Japan the birth year begins on January 1st, which is different from China, where the birth year begins on Chinese Lunar New Year, usually in February

The 12 Asian zodiac animals are combined with the five basic phases (gogyo) to form a cycle of 60. Also, yin and yang (in and to in Japanese) years alternate with one another, and each of the five phases has both a yin and a yang form. Hare years are always yin, representing the female, soft and cool principles of the universe. [Source: Kevin Short, the Daily Yomiuri]

Japanese fortuneteller Year of Rat : 1972, 1984, 1996, 2008, 2020...

Year of Ox: 1973, 1985, 1997, 2009, 2021...

Year of Tiger : 1974, 1986, 1998, 2010, 2022...

Year of Rabbit: 1975, 1987, 1999, 2011, 2023...

Year of Dragon : 1976, 1988, 2000, 2012, 2024...

Year of Snake: 1977, 1989, 2001, 2013, 2025...

Year of Horse: 1978, 1990, 2002, 2014, 2026...

Year of Goat: 1979, 1991, 2003, 2015, 2027...

Year of Monkey: 1980, 1992, 2004, 2016, 2028...

Year of Rooster : 1981, 1993, 2005, 2017, 2029...

Year of Dog : 1982, 1994, 2006, 2018, 2030...

Year of Pig : 1983, 1995, 2007, 2019, 2031...

This basic Asian cosmology was developed in ancient China and brought to Japan with other elements of continental culture. Illustrations of the 12 zodiac animals decorate the walls of the burial chamber in the Kitora Tomb at Nara, thought to date to the late seventh century. The animals are arranged around the walls in directional positions, with the hare standing due east. The early Japanese would have readily recognized most of the zodiac animals. Only the dragon and tiger might have seemed a bit strange. The zodiac hare, of course, could immediately be associated with a familiar countryside animal, the nihon-nousagi or Japanese hare.

Birth rates in Asia go up in years of the dragon, considered an auspicious sign, and decline in years of the tiger, considers a sign that produces difficult children. A 10-year cycle that runs concurrently with 12-year cycle defines whether years in the 12-year cycle are auspicious or inauspicious ones. The year 1966 — the Year of the Fiery Horse — was regarded as a bad year for girls and was marked by a significant reduction in births." It was said girls born that years suffer from a “dire fate” and would be "un-marriageable man eaters." The year 2007 — the Year of the Gold Pig — was regarded as a good year to have children because there was a good chance they would be rich. The next Fiery Horse year is 2026.

See Separate Article CHINESE ZODIAC AND LUCKY BIRTH YEARS factsanddetails.com

Traditional Calendars and Auspicious Days in Japan

Until the 1870s, Japan used a lunar calendar with six-day cycle that specified, often in excruciating detail, what days and even hours were lucky or unlucky. The calendars were based on Chinese calendars brought to Japan in the 14th century. Although the traditional lunar calendar was outlawed during the Meiji period it continues to be used to determine auspicious and inauspicious days.

Many Japanese consult the lunar calendar for “taian”, lucky days, before making decisions on when to go on business trips, conduct important meeting or engage in other important activities. According to one study 3.3 percent of Japanese patients stay in the hospital longer than they have to so they can be discharged on an auspicious day.

Sundays in November are hugely popular days for getting married. The third Sunday of November (Good-Luck Sunday) is often considered particularly auspicious. The Sundays preceding “butsumetsu” (bad luck days) are regarded as unlucky and many hotels and wedding halls offer 30 percent discounts for wedding ceremonies held on these days but even then there are few takers. The New Otani Hotel in Tokyo, for example, had 27 weddings on Good-Luck Sunday one year and only three on Bad-Luck Sunday. “11-12" is auspicious because it can also be pronounced as “good husband and wife.”

There are also lucky and unlucky years. One year in the mid-1960s featured a marked reduction in births because it was regarded as a year for girls "whose fate would be dire" and who would be "un marriageable." Lucky and unlucky years are usually determined by the Chinese calendar.

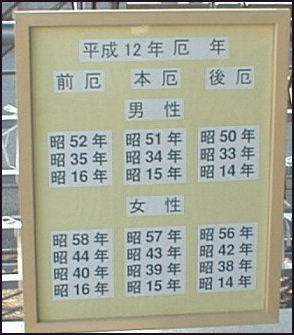

Unlucky Yakudoshi Years

omikuji good luck paper Yoshiko Kosaka wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Yakudoshi is a Japanese folk custom that warns that a person is more likely to experience misfortune or illness at specific ages. To avoid bad things from happening, it is believed one should live modestly during those years. Generally, men are believed to go through two periods of yakudoshi at ages 25 and 42, while women experience yakudoshi at 19 and 33. Under the yakudoshi concept, a person is 1 year old at birth since the period between conception and birth is considered the first year of life. Year 2 begins at the start of following year. [Source: Yoshiko Kosaka, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 7, 2012]

There are various stories why yakudoshi is set at those ages. Some say it comes from the 12-year cycle of the Chinese "eto" astrological calendar, while other say it's a play on words. For example, in Japanese, "19" is read as "juku," which can also be written using kanji meaning "multiple suffering," while "33" can be read as "san-zan," meaning "hideous." Yakudoshi ages are also calculated differently depending on the shrine or temple.

The Fukuoka-based private research institute Anti-Aging Laboratory, which was established by a health food company, conducted a survey in August on 2,000 people aged between 30 and 69. According to the survey, 32 percent of respondents "care about yakudoshi," and 36 percent said they had gone to temple or shrine to receive "yakuyoke" or "yakubarai" blessings to ward off misfortune. More than 40 percent said they believed they were more likely to become sick during yakudoshi years.

The Anti-Aging Laboratory then studied the relationship between aging and illness to propose a set of "new yakudoshi" to promote health awareness. With support from the Tokyo-based Japan Medical Data Center, the lab analyzed the medical bills of about 1 million people to measure the frequency of seven health conditions, such as cerebrovascular disease, dementia and cancer, at particular ages. According to the results, illnesses were more likely to occur in men at the ages of 24, 37, 50 and 63, and at 25, 39, 52, and 63 in women. These ages were then set as the new yakudoshi. "We hope the new yakudoshi will become a good opportunity for people to review their lifestyles so they can live longer lives," said Anti-Aging director and arteriosclerosis expert Hiroshige Itakura.

Young people in particular also seem to be interested in yakudoshi. Iwashimizu Hachimangu in Yawata, Kyoto Prefecture, a shrine known for specializing in yakuyoke, has seen an increase in the number of young people visiting for that purpose. "They seem to think of this shrine as a 'power spot.' I'm often asked to explain about yakuyoke," said Norito Sakurai, a spokesperson for the shrine. Meanwhile, many women in their 30s have taken to visiting Nishiarai Daishi in Adachi Ward, Tokyo. According to the temple, 37 is also an unlucky age for women and as a result, many women who have turned or will turn 37 visit there.

listing of lucky numbers "Yakudoshi has another meaning of 'yaku o morau' [getting a role]. It's considered to have a positive vibe as a turning point in a person's life," said essayist Hiromi Tanaka, an author of a book on yakudoshi. "The number of women who visit shrines or temples for fun has increased over the last couple of years, and I think they are showing some interest in experiencing this old custom in the same way foreigners are interested in seeing Japan," she added.

Lucky and Unlucky Numbers in Japan

Odd numbers and particularly the number 7 are considered lucky in Korea and Japan. The number two is avoided at weddings because it implies something broken in two.

Four is considered an unlucky number because the words for death and four have similar pronunciations. Many hospitals and other buildings don't have a forth floor, the same way some Western buildings don't have a 13th floor. Also, things like dishes and utensils which are sold in sets of four in the United States are sold in sets of five in Japan.

Many Japanese superstitions are based on puns. Four sen coins used to be sewn into clothing to ward off evil spirits and/or bring luck. These drive off shisen, which means "4-sen" but is also a word for death.

Nine is another unlucky number. Sometimes if a customer receives a bill for 9,000 yen, he or she will round it off to 10,000 yen. Eight has traditionally been a sacred number in Japan while nine has been a sacred number in China.

Blood Types and the Japanese

blood type condoms Many Japanese believe that blood type is an important indicator of personality and likelihood for success. Baseball and sumo commentators often have long discussions about the blood type of the competitors and women are careful about not getting stuck with a boyfriend whose blood type is incompatible with theirs. After morning news shows and afternoon talk shows some networks offer advise for people for that day based on their blood type. One network aired a sitcom about the life of a businessman called I Am Type O.

People with O blood are considered calm, strong-willed confident, outgoing, goal-oriented, passionate, curious, generous but stubborn needy, manipulative and ambitious. Those with A blood, the most common blood type in Japan, are regarded as boring, reserved, indecisive, self-sacrificing, sensitive perfectionists, full of worry, overanxious. and nitpicky Those with B blood are said to be cheerful, independent, talkative, sociable, sweet, pushy, eccentric, selfish loud, sloppy and free-spirited. Those with AB blood are said to be creative, kind, interesting to talk to, mysterious but unpredictable — B on the outside but A on the inside.

On being blood type A, Kumiko Makihara wrote in the New York Times, “I am stereotyped as hard-nosed enough to have decided to go it alone, blithe from surviving dealings with all sorts of people and having the seriousness attributed in popular beliefs here to people of my blood group.

Blood types beliefs are relatively modern (blood types were only discovered in 1901) and have been traced to a widely read paper written in 1916 by a Japanese doctor that linked blood type with temperament. In 1925, the Japanese military began gathering data on blood types in an effort to determine the strengths and weakness of soldiers. In the 1930s, the Japanese imperial government reportedly used this information as part of an effort to breed better soldiers. In World War II, army and navy battle groups were reportedly set up according to blood type.

Theodore Bestor, a professor of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, told the New York Times: “In everyday life in Japan , blood type is used as a kind of a social lubricant, a conversation starter. It’s a piece of information that supposedly gives you some idea of what that person is like as a human being.” An editor with the publisher of the best-selling books on blood type told AP that the appeal come from having one’s self-image confirmed.

Blood Type Mania in Japan

blood type condom

vending machine Japanese talk about blood type the same way Americans talk about astrology signs. Media profiles of major political candidates often include their blood type. And, it is not unusual for job seekers to be asked their blood type in company interviews. Tosgitake Nomi, an author of 30 books on blood types, has sold 6 million copies of her works and has given more than 1,000 speeches at big name corporations such as Hitachi, Toyota, Nissan and several big banks. For a while one real estate company required its staff to wear names tags with their names and blood type.

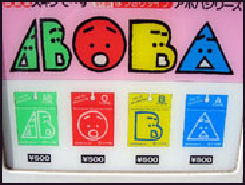

Products based on blood-types include soft drinks, chewing gum, and calendars. Lemon-flavored soda for people with type A blood contains Vitamin C and calcium to calm tense nerves; apple-flavored type O soda has multi-vitamins to help "burn energy more efficiently;" and banana-flavored type AB soda has extra magnesium to reduce stress. Type B soda reportedly increases the "mental stamina" of type B people who "use a lot of brainpower because they are always curious." The main purchaser of these products appears to be schoolgirls.

The Japanese purchase almost 2 million blood-type condoms every year. The condoms for type A are pink and thinner than normal condoms. Those for type B are ribbed, while those for type AB are covered with diamond-shaped studs. The condoms are often accompanied with advise on getting along with partners of various blood types. Purchasers of Type O condoms are told that woman with AB blood are "a hot love" and adds "the key is how tolerant you can be of her selfishness."

Department stores offer special luck bags based on blood type. Matchmakers provide blood type compatibility tests. Some kindergarten organize their classes and some companies make decisions about assignment based in blood type. The woman’s softball team that won the gold medal at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing customized players training according to their blood type.

In 2008, four of Japan’s top 10 bestsellers were books on how blood type determines personality. The books — one of each blood type, B, O, A and AB — had a combined sales of more than 5 million copies. The same year Prime Minister Taro Aso revealed his blood type (A) on his official profile on the Internet, Nintendo offered a DS game with blood type as a key component and a television network was creating a comedy about women seeking husbands based on blood type.

Fortunetelling in Japan

Fortunetelling is a multibillion dollar industry in Japan, with fortunetellers using almost every type of fortuneteller method available: tarot cards, I-ching, Chinese astrology, Western astrology, palm reading and some new kinds that are uniquely Japanese.

The side streets of Omotesando Avenue in Harajuku, Tokyo abound with fortune tellers. Some charges as little as ¥500 for five minute palm reading and answers to questions asked by the customer. Most of the clients are young girls or women in their 20s who ask questions about their boyfriends.

One customer who was told her fortune after giving a "madam" a piece of paper with her and her boyfriend's names and birthdays told the Daily Yomiuri, "She was just so vague, and she kept repeating the thing over and over. Oh well, what do you expect for ¥500."

In Japan, there are cubicle-style halls with every kid of divination, fortunetelling booths in department stores, and tables set up outside in entertainment districts. The latter are often manned by people with no training. There are also a number of fortunetelling services offered on the Internet and cell phones, The majority of their customers are women. The service generally cost around ¥300 to ¥500 a month.

History of Fortunetelling in Japan

touching a lucky deity Over the centuries, Japanese have used a wide variety of amulets and talisman to ward off evil spirits. During the 8th century, physiognomy (judging a person’s character from their facial features was introduced from China. In the 10th century, “onmyodo” (a method of fortunetelling based on Chinese philosophy and astronomy) became as influential as a major religion. One of its chief practitioners Abe no Seimei (921-1005) gave advise to emperors and generals that shaped domestic politics and foreign relations. Seimei is well known in Japan today and occasionally pops in films and manga.

In the Edo period, curses were dispensed by people wearing white robes and mirrors around their necks and candles on their heads. The curses were made at 2:30am, by placing nails in straw dolls.

In the Meiji era, fortuntelling was banned until 1906 when it reemerged, publically anyway, in a women’s magazine. a popular technique involved placing a lid of a rice vat on three bamboo sticks arranged in a tripod. Movement of the lid offered clues about the future.

Fortunetellers began showing up in department stores in Tokyo in the 1960s. In Osaka in the 1970s, ticket vending machines were used for the first time to issue tickets at a set price for fortunetellers as part of an effort to make them seem less unsavory and more respectable.

Expensive Japanese Fortunetellers

Half sessions with profession psychics cost ¥5,000 or more. The Tarim Group in Tokyo, which tarns many of these professionals, offers classes in 50 different kinds of fortunetelling, including palmistry, tarot cards, astrology, feng shui and medicine cards.

Tarim offers its own fortunetelling services. Their headquarters are filled with the autographs and photographs of celebrity clients and small rooms, with curtains instead of doors, where the fortunetellers meet their clients.

One Tarim fortuneteller, who specialized in tarot cards and feng shui told the Daily Yomiuri, "A lot of my clients don't necessarily come to me for fortune telling; they just want someone to listen to their problems." She too said most of her clients where your women who wanted advise on their relationships.

One of the most famous and expensive fortunetellers in Japan is Miwa Akihiro — a yellow-haired transvestite who was former singer an lover of the writer Miyashima, who committed ritual suicide in the 1960s. She-he is commonly seen on Japanese television.

Fortunetelling Methods and Good Luck Charms in Japan

fortune telling machine Japanese fortune methods include: “omikuji” (paper fortunes available at Shinto shrines, especially during the New Year holidays); traditional fortune charts; “kokkuri-san” (a gamelike technique that uses coins believed to be possessed by animals such as foxes with supernatural powers); wishmaking sheets (in which people write wishes on the right side of a card and receive an answer when he left side is heated) and “Dobutsi Uranai” (animal fortunes based on Chinese yin and yang theory and the five elements).

Marks left by chops are read for fortunes. The pronunciation of a name or number of lines required to write the name in kanji or katakana can also indicate good luck or bad luck.

“Omamori” are charms that first appeared centuries ago to keep the gods alert and drive evil spirits away. Sold at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines for between $5 and $20, they are usually made of paper or wood and inscribed with sacred writings and kept in silk sacks They are kept close to the person, in a pocket or purse, like a rabbits foot. In recent times they have made a comeback and used for modern concerns like winning the lottery, passing exams and preventing car crashes.

Most Japanese have at least one omamori. Many have several dozen. Famous sports figures and astronauts swear by them. Some Japanese buy them for their pets or have them downloaded on their cell phone screens. Sociologist have said that omamori have made a come back due to the stress of life in Japan.

See Seven God of Good Luck Above

Shinto Good Luck

Special talismans are purchased at Shinto shrines to bring good luck and ward off evil spirits. They include arrows, small charms and votive plaques (“emu” or “ema”) which have a blank side on which people can write a wish or request.

In most Shinto shrines there is a wall covered with wooden ema that contain requests written to kami. Common requests include good luck in finding a marriage partner or having a child or success with a business or an important exam. The word ema mean “horse,” a reference to the old days when it was believed that horses were messengers for kami.

People usually make the ema themselves. They often have a horse and other objects on the front and their names and addresses on the back. Pictorial symbols are often used to express the request. A target with an arrow, for example, is a request to pass an exam. Images also often represent the kami the request is addressed to.

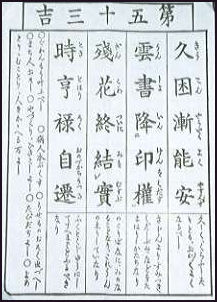

Fortunes (“omikuji”) are determined by selecting bamboo sticks from a box and choosing a fortune according to the number on the stick or simply pulling a folded paper from a box. Luck is classified into “dai-ichi” (great luck), “kicki” (good fortune), “sho-kichi” (middle good fortune) and “kyo” (bad luck). If you like your fortune you can keep it. If you don’t like it you can tie it to a branch on a tree on the shrine grounds.

The omikujo sheets include a horoscope-like predictions of the years events, with sections on business, health and love. Some larger shrines offer these in English.

Animal and Food Fortunetelling in Japan

Animal fortunetelling became popular in Japan after the publication in 1999 of a pocket-size guide, “Human Nature Through Animal Fortunetelling”. Combining elements of Chinese and Western astrology, it categorizes individuals, based on the year and date of their birth, as one of 12 creatures: elephant, cheetah, tiger, tanuki (raccoon dog), monkey, black leopard, sheep, koala, lion, wolf, deer and winged horses.

Like astrology, each creature is linked with different characteristics and personality traits and gets along well with some creatures bit not others. Many newspapers and websites list daily fortunes for each creature.

Kaiten-zushi fortune telling predicts the future and provides advise on financial, family and personal matters based on which five out of 12 sushi dishes an individual picks at a kaiten-zushi (moving sushi restaurant). You can also find Japanese websites that offer fortunes and advise based on yakatori bar selections, sea creatures (determined by birthday and blood type), cell phone numbers, subway stop on Tokyo's Yamanote Line, vegetable signs and monsters (including a werewolf, Dracula and Medusa).

Weird Fortunetellers in Japan

The film “Shocking Asia”, showed a female fortunetellers on the streets of Japan who predicted the future by examining her customer's anus. The clients entered a van, paid a fee, pulled down their pants and the woman examined anuses and told them their fortunes.

In Kobe there is a fortune teller who predicts the future by studying the route walked by a queen ant on a tabletop.

Fortunetelling Scams in Japan

In recent years there have been a number of reports of fortunetellers demanding that their clients fork over large amounts of money’sometimes thousands of dollars — for things like a years worth of prayers or the recovery of lost spiritual power. One religious organization was ordered by the Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry to shut down its “change of fortunes” business on the grounds that it was using fraudulent means to obtain money from gullible people.

In one exchange recorded at a hotel, a woman in her 70s was told her son’s life was weakening by a fortuneteller and told she could remedy the situation by paying $10,000 for a year’s worth of prayers. When the woman said she couldn’t afford that she was told she could the service for $7,300. The next day she withdrew the money from her bank account and turned it over to the fortuneteller.

One former fortuneteller told the Yomiru Shimbun that she took a training course in which was that told that if an advice seeker was a woman, tell her she was “possessed by the ghost of an unborn baby.” If the woman said she never had an abortion or miscarriage the fortuneteller was advised to say. “Well, it must be the ghost of your mother’s lost baby.” The fortuneteller trainee was told to base the fees she charged “on how wealthy the advice-seeker seemed to be.”

In Tokyo there are healing salons that offer fortune-telling based on divination and names sell goods such as Buddha paintings and charms against evil and inflated prices The owners of one salon was arrested for swindling a 44-year-old business man out of $40,000.

Image Sources: 1) touching deity, good luck machines, lucky paper, Ray Kinnane 2) blood type condoms, Japan Visitor, 3) drawn pictures and diagrams, JNTO 4) lucky cat, lucky numbers, goods from Japan websites, fortunetellers, Japan-Photo.de

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2021