JAPAN IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Views of Japan in the West Harvard Prof. Joseph Nye told the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Japan is an amazing society that reinvented itself in the Meiji [Restoration], and became the first Asian power to deal with globalization. After 1945, it did it again and became the second largest economy in the world.”

The Meiji era ended with the death of the emperor in 1912 and the accession of Crown Prince Yoshihito as emperor of the Taisho period (Great Righteousness, 1912-26). The end of the Meiji era was marked by huge government domestic and overseas investments and defense programs, nearly exhausting the country’s credit, and a lack of foreign exchange to pay debts.

Good Websites and Sources: Essay on 20th Century Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on Imperial Japan 1894-1945 aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Another Essay on Imperial Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on Empire of Japan Wikipedia ;Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ;After the Russo-Japanese War Images MIT Visualizing Culture ; Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 dl.lib.brown.edu/kanto ; 1923 Tokyo Earthquake Photo Gallery japan-guide.com Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com;

MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) EMPEROR, LEADERS AND STATE SHINTO factsanddetails.com;

MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) REFORMS, MODERNIZATION AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com;

RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com;

JAPAN BEFORE WORLD WAR II: THE RISE OF JAPANESE MILITARISM AND NATIONALISM factsanddetails.com;

EMPEROR HIROHITO factsanddetails.com;

GREAT TOKYO EARTHQUAKE OF 1923 factsanddetails.com;

SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com;

JAPAN GEARS UP FOR WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com;

JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Culture of the Quake: The Great Kanto Earthquake and Taisho Japan (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2015) Amazon.com; “Party Rivalry and Political Change in Taisho Japan” (Harvard East Asian Series, 35) by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century” by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan” by Christopher Benfey (Random House, 2003) Amazon.com; “Imperialism in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries —With a Focus on the Case of Japan in Korea” by John B. Duncan Amazon.com; “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert P Bix Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com

Political Rivalries in the Late Meiji Period

Yamagata Aritomo

After the bitter political rivalries between the inception of the Diet in 1890 and 1894, when the nation was unified for the war effort against China, there followed five years of unity, unusual cooperation, and coalition cabinets. From 1900 to 1912, the Diet and the cabinet cooperated even more directly, with political parties playing larger roles. Throughout the entire period, the old Meiji oligarchy retained ultimate control but steadily yielded power to the opposition parties. The two major figures of the period were Yamagata Aritomo, whose long tenure (1868-1922) as a military and civil leader, including two terms as prime minister, was characterized by his intimidation of rivals and resistance to democratic procedures, and It , who was a compromiser and, although overruled by the genro, wanted to establish a government party to control the House during his first term. When Ito returned as prime minister in 1898, he again pushed for a government party, but when Yamagata and others refused, Ito resigned. With no willing successor among the genro, the Kenseito (Constitutional Party) was invited to form a cabinet under the leadership of Okuma and Itagaki, a major achievement in the opposition parties' competition with the genro. [Source: Library of Congress]

This success was short-lived: the Kenseito split into two parties, the Kenseito led by Itagaki and the Kensei Honto (Real Constitutional Party) led by Okuma, and the cabinet ended after only four months. Yamagata then returned as prime minister with the backing of the military and the bureaucracy. Despite broad support of his views on limiting constitutional government, Yamagata formed an alliance with Kenseito. Reforms of electoral laws, an expansion of the House to 369 members, and provisions for secret ballots won Diet support for Yamagata's budgets and tax increases. He continued to use imperial ordinances, however, to keep the parties from fully participating in the bureaucracy and to strengthen the already independent position of the military. When Yamagata failed to offer more compromises to the Kenseito, the alliance ended in 1900, beginning a new phase of political development.

Ito and a protégé, Saionji Kimmochi (1849-1940), finally succeeded in forming a progovernment party--the Seiyokai (Association of Friends of Constitutional Government)--in September 1900, and a month later Ito became prime minister of the first Seiyokai cabinet. The Seiyokai held the majority of seats in the House, but Yamagata's conservative allies had the greatest influence in the House of Peers, forcing Ito to seek imperial intervention. Tiring of political infighting, Ito resigned in 1901. Thereafter, the prime ministership alternated between Yamagata's protégé, Katsura Taro (1847-1913; prime minister 1901-5 and 1908- 11), and Saionji (prime minister 1905-8 and 1911-12). The alternating of political power was an indication of the two sides' ability to cooperate and share power and helped foster the continued development of party politics.

Taisho Period 1912-1926)

Emperor Taisho

The Taisho Period (1912-1926) is defined by the rule of Emperor Yoshihito (also known as Emperor Taisho), who ascended the throne in 1912 and died in 1926. The Taisho Emperor is remembered most for his grand German-style uniforms, his Kaiser Wilhelm-style mustache and madness. The son of the Meiji Emperor Mutsuhito, he tried to be come a truly popular leader. But in the end the ruling oligarches were threatened by his attempts to endear himself to the public and isolated the Imperial Family into "birds in a cage."

In his last years the Taisho Emperor suffered from a deteriorating intellect, a condition that may have been caused by meningitis. He was removed from public view after he rolled up a manuscript of speech during a formal session of the Diet and peered through it as if were a telescope. His son, the future Emperor Hirohito, became a regent for his father at age of 21.

The beginning of the Taisho era was marked by a political crisis that interrupted the earlier politics of compromise. When Saionji tried to cut the military budget, the army minister resigned, bringing down the Seiyokai cabinet. Both Yamagata and Saionji refused to resume office, and the genro were unable to find a solution. Public outrage over the military manipulation of the cabinet and the recall of Katsura for a third term led to still more demands for an end to genro politics. Despite old guard opposition, the conservative forces formed a party of their own in 1913, the Rikken Doshikai (Constitutional Association of Friends), a party that won a majority in the House over the Seiyokai in late 1914.

Japan in the Taisho Period

During the Taisho period, Japan experimented with parliamentary democracy, joined the League of Nations (1920), and practiced a generally moderate and nonaggressive foreign policy. It also saw the rise of large industrial and banking conglomerates known as “zaibatsu”.

But in the end true power was in the hands of the zaibatsu and militarists. As time went on Japan's constitutional government was usurped by aggressive, militarist, expansionist leaders that moved the nation further along in the direction of World War II.

The two-party political system that had been developing in Japan since the turn of the century finally came of age after World War I. This period has sometimes been called that of "Taish Democracy," after the reign title of the emperor. In 1918 Hara Takashi (1856-1921), a protégé of Saionji and a major influence in the prewar Seiyokai cabinets, had become the first commoner to serve as prime minister. He took advantage of long-standing relationships he had throughout the government, won the support of the surviving genro and the House of Peers, and brought into his cabinet as army minister Tanaka Giichi (1864-1929), who had a greater appreciation of favorable civil-military relations than his predecessors. Nevertheless, major problems confronted Hara: inflation, the need to adjust the Japanese economy to postwar circumstances, the influx of foreign ideas, and an emerging labor movement. Prewar solutions were applied by the cabinet to these postwar problems, and little was done to reform the government. Hara worked to ensure a Seiyokai majority through time-tested methods, such as new election laws and electoral redistricting, and embarked on major government-funded public works programs. [Source: Library of Congress]

Political Upheaval in Japan in the 1920s

The public grew disillusioned with the growing national debt and the new election laws, which retained the old minimum tax qualifications for voters. Calls were raised for universal suffrage and the dismantling of the old political party network. Students, university professors, and journalists, bolstered by labor unions and inspired by a variety of democratic, socialist, communist, anarchist, and other Western schools of thought, mounted large but orderly public demonstrations in favor of universal male suffrage in 1919 and 1920. New elections brought still another Seiyokai majority, but barely so. In the political milieu of the day, there was a proliferation of new parties, including socialist and communist parties. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In the midst of this political ferment, Hara was assassinated by a disenchanted railroad worker in 1921. Hara was followed by a succession of nonparty prime ministers and coalition cabinets. Fear of a broader electorate, left-wing power, and the growing social change engendered by the influx of Western popular culture together led to the passage of the Peace Preservation Law (1925), which forbade any change in the political structure or the abolition of private property. *

Unstable coalitions and divisiveness in the Diet led the Kenseikai (Constitutional Government Association) and the Seiy Honto (True Seiyokai) to merge as the Rikken Minseito (Constitutional Democratic Party) in 1927. The Rikken Minseito platform was committed to the parliamentary system, democratic politics, and world peace. Thereafter, until 1932, the Seiyokai and the Rikken Minseito alternated in power. *

Japanese Communists

Despite the political realignments and hope for more orderly government, domestic economic crises plagued whichever party held power. Fiscal austerity programs and appeals for public support of such conservative government policies as the Peace Preservation Law--including reminders of the moral obligation to make sacrifices for the emperor and the state--were attempted as solutions. Although the world depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s had minimal effects on Japan--indeed, Japanese exports grew substantially during this period--there was a sense of rising discontent that was heightened with the assassination of Rikken Minseito prime minister Hamaguchi Osachi (1870-1931) in 1931. *

Social Movements and Communism in Pre-World War II Japan

The events flowing from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 had seen not only the fulfillment of many domestic and foreign economic and political objectives--without Japan's first suffering the colonial fate of other Asian nations--but also a new intellectual ferment, in a time when there was interest worldwide in socialism and an urban proletariat was developing. Universal male suffrage, social welfare, workers' rights, and nonviolent protest were ideals of the early leftist movement. Government suppression of leftist activities, however, led to more radical leftist action and even more suppression, resulting in the dissolution of the Japan Socialist Party (Nihon Shakaito), only a year after its 1906 founding, and in the general failure of the socialist movement. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The victory of the Bolsheviks in Russia in 1917 and their hopes for a world revolution led to the establishment of the Comintern (a contraction of Communist International, the organization founded in Moscow in 1919 to coordinate the world communist movement). The Comintern realized the importance of Japan in achieving successful revolution in East Asia and actively worked to form the Japan Communist Party (Nihon Kyosanto), which was founded in July 1922. The announced goals of the Japan Communist Party in 1923 were an end to feudalism, abolition of the monarchy, recognition of the Soviet Union, and withdrawal of Japanese troops from Siberia, Sakhalin, China, Korea, and Taiwan. A brutal suppression of the party followed. Radicals responded with an assassination attempt on Prince Regent Hirohito. The 1925 Peace Preservation Law was a direct response to the "dangerous thoughts" perpetrated by communist elements in Japan. *

The liberalization of election laws, also in 1925, benefited communist candidates even though the Japan Communist Party itself was banned. A new Peace Preservation Law in 1928, however, further impeded communist efforts by banning the parties they had infiltrated. The police apparatus of the day was ubiquitous and quite thorough in attempting to control the socialist movement. By 1926 the Japan Communist Party had been forced underground, by the summer of 1929 the party leadership had been virtually destroyed, and by 1933 the party had largely disintegrated. *

Great Tokyo Earthquake of 1923

Great Tokyo Earthquake of 1923

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the most destructive earthquake ever was the Kanto earthquake that struck the Tokyo and Yokohama areas at 11:58am on September 1, 1923. It measured 7.9 on the Richter scale and occurred when a section of the Philippine Sea plate suddenly shifted under the Kanto Plains. The epicenter was in Sagami Bay off Yokohama.

At the time of the quake Tokyo had a population of 2½ million and the area struck by the quake had 12 million. A total of 142,907 people were killed or reported missing. The tremors and fires injured 502,000 and left 3.25 million homeless. About 80 percent of the dwellings in Yokohama and 60 percent of those in Tokyo were destroyed. One survivor said, "It was like a scene from hell. When the fires subsided, I walked around and saw corpses everywhere. I'd thought I was hot — but even the soles of their feet were charred."

The Tokyo earthquake occurred as many Tokyo residents were firing up braziers for lunch. The braziers fell over and set houses and entire neighborhoods on fire. The fire spread with the help of strong winds generated by a typhoon that was northern Japan at the time. Winds channeled through the streets created vortexes at intersections and ?fiery whirlwinds developed into tornados, which incinerated everything.” People were also killed by mudslides, landslides and tsunamis. In Shizuoka, the entire village of Nebukawa was wiped out by a landslide. Riots broke out in central Tokyo.

The Tokyo earthquake was a actually a series of quakes that lasted for about 10 minutes. This first quake, measuring 7.9 on the Richter scale, increased in intensity for 12 second and caused violent shaking that lasted for five seconds. Three minutes later there was a 7.3 quakes. For and half minutes after that there was a 7.3 temblor. Later in the day hundreds of aftershocks were recorded, 19 of them with magnitudes of 5 or higher.

The Tokyo earthquake was carefully documented and studied. After the quake many changes were made and many safety measures were implemented. There was some discussion of moving the capital from Tokyo.

Book: “Earthquakes in Human History” by Jelle Zeilinga de Boer and Donald Theodore Sanders (Princeton University Press). The describes earthquakes in the Dead Sea, Britain, Sparta in 464 B.C.; Lisbon in 1755; New Madrid Mo., in 1811; San Francisco in 1906; Tokyo in 1923; Peru in 1970; and Nicaragua in 1972.

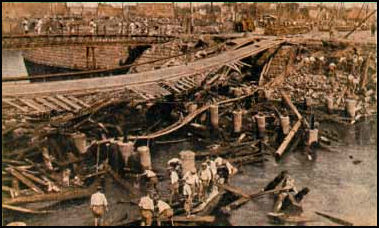

Damage During the Great Tokyo Earthquake

During the earthquake office buildings toppled into the streets, ships were cast adrift when their hawsers snapped, railroad tunnels collapsed, 394 trams cars overturned, offshore oil tanks exploded setting Tokyo Bay on fire and 16-foot waves tossed a commuter train and its 500 passengers into the sea. People flocked to parks and other open spaces for safety, but many of them died by the choking fumes from all the fires.

Damage occurred in Kanagawa Chiba, Ibaraki, Saitama, Yamanashi and Shizuoka prefectures as well as in Tokyo and and Yokohama. One survivor recalled. "The pillars of the house made groaning sounds and began to crack. An earthquake! The wall clock stopped, and the electric fan went flying."

Mass hysteria broke out. Food and medical supplies were quickly used up and 9 million people were without drink water. Emperor Hirohito's wedding was postponed a year.

One of the few buildings to survive the earthquake was Imperial Hotel designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The "earthquake proof" building utilized the "floating concept" which meant that it rested on concrete and steel piers sunk into a 70-foot-thick bed of mud. The earthquake occurred hours before the hotel's official grand opening ceremony.

See Separate Article GREAT TOKYO EARTHQUAKE OF 1923 factsanddetails.com

Lynching During the Great Tokyo Earthquake

An estimated 6,000 Koreans and a smaller number of Chinese were lynched several days after the earthquake by vigilant mobs in search of scape goats.

The slaughter began after the Interior Ministry cabled local branches that ethnic Koreans were committing acts of arson and ordered them rounded up. Rumors began spreading that Koreans were looting and poisoning the water supply. Some Japanese even accused them of causing the earthquake. Japanese mobs hunted down Koreans and beat them to death. Even in places that were not damaged by the quake, Koreans were viscously attacked.

Right-wing extremists used the confusion as an opportunity to go after labor unionists and socialists. Military police attacked "enemies of the state." In the infamous "Kamoedo Incident,” army officers butchered10 labor activists with swords. Martial law was declared for a week.

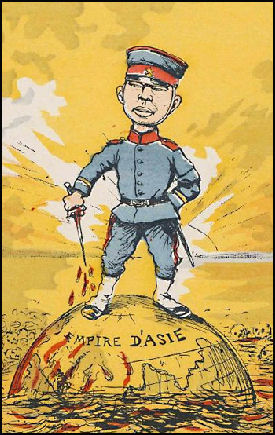

Image Sources: 1) political cartoons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 2) Earthquake pictures, J.B. Macelwane Archives, St. Louis University 3) Hirohito pictures, Wikipedia

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012