HEALTH IN HEIAN-ERA JAPAN

Nara-era toilet paper

Japanese historian Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: “The “actual living conditions in and around the imperial court were, by today’s standards, unimaginably unsanitary and unnatural. According to books on the history of epidemic disease and medical treatment, aristocratic women, on average, died at age 27 or 28, while men died at age 32 or 33. In addition to the infant mortality rate being extremely high, the rate of women dying at childbirth was also high. Another reason for these figures was physical weakness and a lack of exercise. [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits ++]

“The lamps of the time consisted of an oil-filled vessel attached to a candle holder, in which two wicks burned. The resulting light was about two candles in strength. Any distance from the light source greater than about fifteen centimeters would render reading impossible. What an unflattering image: Murasaki Shikibu’s nostrils must have been jet back from the oil smoke. ++

“Murasaki Shikibu herself died at around age 40. Her lifespan was slightly shorter than that of Sei Shonagon, but by the standards of the time was a long, full lifespan. Murasaki, who caught a glimpse of the elder Sei Shonagon living beyond 40, expressed the sentiment that women would be better off dying early. In addition to the attitude that women loose their value as women when their charm deteriorates, in fact, there surely would have been very few white-haired, wrinkled old grandmothers in existence. Looking at the specific causes of death at the time, tuberculosis (possibly including pneumonia cases) accounted for 54 percent, beriberi for 20 percent, and diseases of the skin (including smallpox) for 10 percent. According to a courtier diary account of that time, his scabs itched so much that he could not sleep, so he spent the whole night riding a horse around the base of Mt. Higashi. ++

“Finally, there is the matter of the winter cold. The late Heian period corresponds to the time when Japan’s climate was at is coldest and was much colder than today. Nevertheless, the palaces, and, of course, the individual aristocratic residences featured wooden floors and no ceiling boards. In wide, expansive rooms of 20-30 tsubo [one tsubo = 3.95 square yards or 3.31 square meters], a subitsu (rectangular hibachi) or a hioke (an oval-shaped hibachi) would hardly be sufficient for warming. When sleeping, in addition to today’s futon, they used a large cloth called a fusuma. However, many nights would have been cold, and sleep would have been difficult. In that case, it would probably not be long before [these aristocrats] would have started conjuring up vengeful spirits and mononoke in their minds.” ++

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTOS VERSUS THE TAIRA CLAN IN THE HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD ARISTOCRATIC SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD LIFE factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN THE HEIAN PERIOD factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan WRITING AND LITERATURE IN THE HEIAN PERIOD factsanddetails.com TALE OF GENJI, MURASAKI SHIKIBU AND WOMEN IN THE STORY factsanddetails.com

Websites on Nara- and Heian-Period Japan: Essay on Nara and Heian Periods aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Nara Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the Heian Period Wikipedia ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji Temple Websites: Enryaku-ji Temple official site hieizan.or.jp; Marathon monks Lehigh.edu ; Tale of Genji Sites: The Tale of Genji.org (Good Site) taleofgenji.org ; Nara and Heian Art Sites at the Metropolitan Museum in New York metmuseum.org ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Tokyo National Museum www.tnm.jp/en ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Emperor and Aristocracy in Heian Japan: 10th and 11th centuries” by Francine Herail and Wendy Cobcroft (2013) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 2: Heian Japan” by Donald H. Shively and William H. McCullough Amazon.com; “The Pillow Book” (Penguin Classics) by Sei Shonagon and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com; “The Tale of Genji” (Penguin Classics) by Royall Tyler and Murasaki Shikibu Amazon.com; “The Halo of Golden Light: Imperial Authority and Buddhist Ritual in Heian Japan” by Asuka Sango Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949–1603" by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds Amazon.com; “The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan” by Mikael S. Adolphson Amazon.com; “The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sohei in Japanese History” by Mikael S. Adolphson Amazon.com; “The Birth of the Samurai: The Development of a Warrior Elite in Early Japanese Society by Andrew Griffiths Amazon.com; “The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan” by Catharina Blomberg Amazon.com; “Buddhism in the Heian period reflected in the Tale of Genji” by Kati Neubauer Amazon.com; “Heian Temples: Byodo-In and Chuson-Ji” (The Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art, V. 9) by Toshio Fukuyama and Ronald K Jones Amazon.com; “Japanese Arts of the Heian Period, 794-1185" by John M Rosenfield Amazon.com;

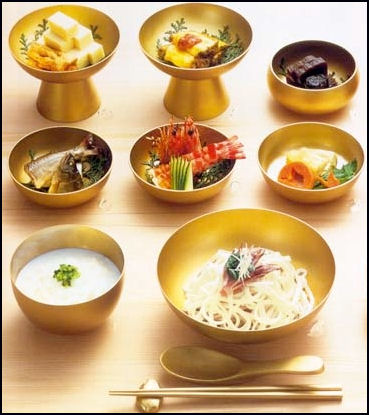

Food and Nutrition in Heian-Era Japan

traditonal kaiseki dishes Buddhist prohibitions on the killing of animals endured. In 927 AD, regulations were enacted that stated that any government official or member of nobility that ate meat was deemed unclean for three days and could not participate in Shinto observances at the imperial court. The the influence of Chinese culture brought chopsticks to Japan around this time. Chopsticks were used mainly by nobility at banquets; most people continued to eat with their hands. Metal spoons were also used during the 8th and 9th centuries, but only by the nobility. Dining tables were also introduced to Japan at this time. Commoners used a legless table called a oshiki, while nobility used a lacquered table with legs called a zen. Each person used his own table. Lavish banquets for the nobility would have multiple tables for each individual based upon the number of dishes presented. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Upon the decline of the Tang dynasty in the 9th century, Japan made a move toward its individuality in culture and cuisine. The spoon was largely abandoned as a dining utensil and commoners were now eating with chopsticks as well. Among the Heian nobility, court chefs prepared vegetables sent as taxes. Court banquets were common and lavish. On the eating habits of commoners, court lady Sei Shonagon wrote in the “Pillow Book”: “The way carpenters eat is really odd. … The moment the food was brought, they fell on the soup bowls and gulped down the contents. Then they pushed the bowls aside and polished off the vegetables. … I suppose this must be the nature of carpenters. I should not call a very charming one.”

The dishes consumed after the 9th century included grilled fish and meat (yakimono), simmered food (nimono), steamed foods (mushimono), soups made from chopped vegetables, fish or meat (atsumono), jellied fish (nikogori) simmered with seasonings, sliced raw fish served in a vinegar sauce (namasu), vegetables, seaweed or fish in a strong dressing (aemono), and pickled vegetables (tsukemono) that were cured in salt to cause lactic fermentation. Oil and fat were avoided almost universally in cooking. Sesame oil was used, but rarely, as it was of great expense to produce. Documents from the Heian nobility note that fish and wild fowl were common fare along with vegetables. Their banquet settings consisted of a bowl of rice and soup, along with chopsticks, a spoon, and three seasonings which were salt, vinegar and hishio, which was a fermentation of soybeans, wheat, sake and salt. A fourth plate was present for mixing the seasonings to desired flavor for dipping the food. +

The four types of food present at a banquet consisted of dried foods (himono), fresh foods (namamono), fermented or dressed food (kubotsuki), and desserts (kashi). Dried fish and fowl were thinly sliced (e.g. salted salmon, pheasant, steamed and dried abalone, dried and grilled octopus), while fresh fish, shellfish and fowl were sliced raw in vinegar sauce or grilled (e.g. carp, sea bream, salmon, trout, pheasant). Kubotsuki consisted of small balls of fermented sea squirt, fish or giblets along with jellyfish and aemono. Desserts would have included Chinese cakes, and a variety of fruits and nuts including pine nuts, dried chestnuts, acorns, jujube, pomegranate, peach, apricot, persimmon and citrus. The meal would be ended with sake. +

Japanese historian Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: The presence of tuberculosis and beriberi — caused by deficiency in vitamin B— “indicate a nutritional imbalance. The reason was that their diet was poor. First, regarding the meat of four-legged animals, owing to Buddhist prohibitions against killing, banishment was the [most severe] punishment, and [the Heian elites] did not eat chicken [and other such meat]. Animal protein came almost exclusively from dried fish and shellfish. However skillfully one might reconstitute these products, their rate of absorption in the digestive tract is low. And a lack of physical activity further slowed digestion. Rice consisted of steamed, half-husked grains, and, while it did provide calories, it was also hard to digest. Fresh seafood was rare. Their only salvation was that at each meal they ate seaweed. [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits]

Long Hair, Eyebrows and the Heian-Era Cult of Beauty

Poetess Ukon

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Heian aristocrats made a cult out of beauty. Of course, what a Heian aristocrat might consider beautiful, someone in different cultural circumstances might consider ugly. In terms of personal appearance, for example, Heian aristocrats regarded white teeth as ugly, particularly for women. "They look just like peeled caterpillars" wrote one critic of a woman who refused to blacken her teeth. To blacken their teeth Heian women applied a sticky black dye to their teeth so that their mouths resembled a dark, toothless oval when open. This particular custom of blackening the teeth (o-haguro) persisted until the 1870s among certain elite groups of Japanese women. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“There were many other aspects of a beautiful personal appearance. Both men and women prized a rounded, plump figure. The face in particular would ideally have been round and puffy. Small eyes were ideal for both sexes, as was powdery white skin. Aristocrats with dark complexions, both men and women, frequently had to apply makeup to appear more pale. Even most capital military officers, many of whom were civilian aristocrats with no military training at all, would not have dared appear in public on formal occasions without makeup. ~

“The majority of Japanese at the time must have appeared quite the opposite of the aristocrats. Peasants and laborers engaged in demanding physical work out of doors. Food was often scarce. These conditions tended to produce lean physiques and dark skin. It seems that in nearly all human societies, beauty and wealth go hand-in-hand. In the Heian period, the plump, pale courtier was obviously someone of privilege, wealth, and leisure. Such a person had the time and resources to attend to her or his appearance. ~

“There were still other standards of personal beauty in Heian times. For women, nature unfortunately put eyebrows in the wrong place. To correct this problem, women plucked out their eyebrows and painted them back on, usually quite thick, an inch or so above their original location, thereby beautifying the face. Also, extremely long hair--longer than one’s own body--was de rigueur for an attractive Heian woman. Washing such hair was an all-day affair requiring the assistance of numerous attendants. Again, notice the connection with wealth and leisure. ~

Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: “The long hair of Heian women is thought to have resulted in large part from young girls slicking down their hair each day with an extract from the Sanekazura tree [a type of magnolia] and the iodine obtained from the seaweed. This matter comes up in a passage from the Okagami about Fujiwara-no-Yoshiko’s marrying into the court of Emperor Murakami: “To enter the palace she got in a palanquin. Her body was inside, but the train of her hair extended all the way to the base of the pillar in her mother’s room.” She must have looked much like a long-tailed rooster. Based on the size of aristocratic houses, her hair must have been nearly five meters in length. Long hair was the foremost aspect of beauty for women of the time. The cropped hairstyles of many women today would, in Heian times, been an indication of a “tare-ama” (a half-hearted nun), a woman who has half-way despaired of the world and given up. In any case, there is no point in cultivating such log hair exclusively if one’s body is frail and unhealthy.” [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits]

“Standards of male beauty were, in many ways, quite similar to those for female beauty. Although men did not shave their eyebrows, idealized depictions of handsome men show the eyebrows high on the forehead. Men would ideally have a thin mustache and/or a thin tuft of beard at the chin. Large quantities of facial hair, however, detracted substantially from one’s attractiveness. Looking at art of the Heian period, or even art of later periods depicting scenes of Heian courtly life, it is sometimes difficult to tell men from women from the face alone. The merging of male and female features is particularly apparent in depictions of children and people in their teenage years. ~

Heian Period Clothes

Heian period clothes

Heian period garments worn by nobles often had multiple layers and took many months to make. Courtiers wore junihitoe, which literally means 12 layers of silken robes but often included as many as 20, weighing several kilograms. The robes often changes according to the season and latest fashions.

In the Heian Period nobles dressed in kariginu robes made of silk and ebosho brimless headgear. Wearing the kariginu straightened the posture and forced one to walk slowly, When doing something one had to use one hand to pull back the dangling sleeves. In the spring nobles wore a white, diaphanous robe over a red inner robe, or visa versa. The two styles (white over red and red over white) appeared pink, but differed slightly expressing the different shades of the color in early and late spring.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Heian aristocrats regarded the nude body as disgustingly ugly. People of taste always adorned themselves with multiple layers of clothing. This clothing was inseparable from the body itself. It provided all manner of possibilities both to enhance the taste and beauty of one’s appearance and to detract from it. First, clothing had to conform to a person’s rank. Other key considerations included social situations (inside one’s house, visiting a temple, participating in a court ceremony, etc.), prevailing weather, and the current season. Women commonly wore five or six layers of robes, the most crucial part of was the sleeves. Each sleeve would be of a slightly different length and color, resulting in multicolored bands of fabric at the ends of the arms. The arrangement of these colors was terribly important for conveying a sense of refinement and good taste. Just one color being a little too pale or a little to bright could easily become a point of criticism. Appearing in colors that blatantly clashed or were inappropriate for the season could ruin a person’s reputation. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Marriage in Heian Aristocrat Society

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “We should pause here to point out that marriage for Heian aristocrats did not normally mean men and women living together in close quarters as it typically does today. Married women often remained in the home of their parents, and these homes were usually large estates containing numerous rooms and apartments. Sometimes women did move to the residence of their husband but usually only in their later years. Even then, they might not live in close proximity to him. A newly-married woman, therefore, would usually await visits from her husband, or, perhaps, someone else. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“Men were allowed multiple wives, though not without socially imposed restrictions such as restrictions concerning the rank of the wives and other partners. In theory and by law, married women were expected to remain faithful to a single husband. In fact, however, multiple sex partners for married women were also acceptable, though any such relationships had to conform to standards of good taste, which included being discreet--or at least going through the motions of being discreet. A quiet rendezvous at a remote Buddhist temple, for example, would have been ideal, if not always practical. In general, men were freer in their sexual relations than women, but aristocratic women in the Heian period were not nearly as restricted in this regard as were their Chinese counterparts or elite women in later ages in Japan.” ~

Women in Heian Aristocrat Society

Taikenmonin

While Prince Genji may be the main character in the famous novel “Tale of Genji”, by Murasaki Shikibu, the real focus of the book, many think, is the thoughts and emotions of the women who love him. Respected author and Buddhist nun Jakucho Setouchi told the Daily Yomiuri, “Shikibu wrote about the pain and joy the women felt in their relationship with Genji and how they overcame their grief. Because she wrote about women’s emotions and their desires, the tale is still enjoyed 1,000 years later."

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Women of aristocratic status spent most of their time as adults sitting in their residences....These residences generally had a few very large open rooms. Portable screens made of fabric and curtains were the major means of dividing these rooms. With servants and attendants to do all the work, including taking care of children, there were relatively few pressing matters requiring attention. “Boredom was a problem for many aristocratic women as they sat behind screens with their attendants. Although women could and sometimes did leave their residences on recreational outings, slow, plodding, uncomfortable ox-drawn carriages and the many social rules about appearance in public often made such outings tedious. Men, by contrast, could always busy themselves with the duties of their political offices. This boredom was a major reason so many aristocratic women turned their attention to the literary arts, a topic we take up in the next section. Excursions to various places, especially to Buddhist temples, were another diversion.” [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Lorraine Witt wrote: “Though a valued member of society, the life of kuge [aristocratic] women during the Heian was much more confined than the life of kuge men. A Woman spent the majority of her life watching rather than participating. She would stay hidden behind a silk screen and under many layers of silk clothing, her face covered with thick makeup (artificial eyebrows and blackened teeth were the trend of the time) and behind a fan. Except for occasional excursions and the necessary ceremonies, she was not supposed to see anyone besides her female attendants, husband, and father. However, promiscuity was an accepted part of the culture of these women and love affairs were expected. [Source: Lorraine Witt, ++ ]

“The affairs, the promiscuity, and the exchanging of poetry between lovers provided much excitement in the life of the kuge. Personal relationships were dramatized in a most extravagant way; both men and women spent incredible amounts of time strategizing how to win a lover and evaluating the significance of his or her lover’s actions. For men isolated from politics and business these affairs offered excitement. “With every detail of everyday life as carefully prescribed as it was in the late Heian, no courtier presumed to be spontaneous or original; court ladies offered his only chance of adventure” (Dilts 91). In a society extremely preoccupied with rank, marriages (or becoming a concubine for the lower classes) offered women a way to move up in society and to make important social ties for their family. For this reason courtiers actually preferred having daughters rather than sons. ++

“When she was not engaging in a love affair, a woman kuge might be found making clothing. Not only would a Heian woman and her attendants need to provide clothing for herself and her family, but she would also need to provide clothing to be given as gifts in ceremonies such as the New Year Celebration. Keeping up with the incredible trends in clothing at this time meant the women spent considerable time making clothing. ++

“However, there was still much time for the women to be educated. They were educated and expected to know how to write artful 31 syllable waka poems in a “women’s calligraphy” style (Hempel 170), but this was not the only writing they did. In her Pillow Book, Sei Shonagon used a less formal, more conversational type of writing unique to women. The Pillow Book, a diary/thought book is one of the best resources into the lives of kuge women. In it she talks about her disdain for the lower classes, adoration of the empresses and emperor, events she has “spied” between people, things she finds entertaining (backgammon, babies, lovers), things she finds boring or without merit (rain, abstinence), to name a few. Another book written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu-nikki, (approximately the year 1000), The Tale of Genji, was the world’s first psychological novel, starring the love life of Prince Gengi. Much subsequent art and many poems would be based on this novel, which became the most celebrated novel of Japan.” ++

Heian-Era Outing to a Buddhist Temple

According to Morris: “For Genji and his circle, the Buddhist church had many diverse functions. In the first place, the numerous temples surrounding the capital offered an opportunity for those excursions and pilgrimages that were one of the main distractions in their somewhat uneventful lives. For women in particular, these visits provided an occasional escape from the claustrophobic confines of their crepuscular houses and an opportunity to glimpse, if only through the heavy silk hangings of their ox-drawn carriages, the wide bright world outside. . . . Visits and retreats to outlying temples also served a very secular purpose in the gallant world of Heian, since they provided an ideal pretext for trysts or adventures of one kind or another; and it appears that the priests of the more fashionable temples were quite prepared to accommodate their aristocratic clients in this respect.” [Source: “The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan” by Ivan Morris (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964)]

In her “Pillow Book,” Sei Shonagon explained the social diversions of visiting Buddhist temples in some detail. For example: “A preacher should be good-looking. For, if we are properly to understand the worthy sentiments of his sermon, we must keep our eyes fixed on him while he speaks; by looking away we may forget to listen. Accordingly an ugly preacher may be a source of sin.”

Another passage from the “Pillow Book” reads: [A] couple of gentlemen who have not met for some time run into each other in the temple, and great is their surprise. they sit down together and chat away, nodding their heads, exchanging funny stories and opening their fans wide so that they could hold them in front of their faces and laugh more freely. They toy with their elegantly decorated rosaries11 and, glancing from side to side, criticize some defect they have noticed in one of the carriages and praise the elegance of another. . . . Meanwhile, of course, they pay not the slightest attention to the service that is going on.”

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Although women normally remained in their carriages during Buddhist services, with some care in the placement of the carriages there was ample opportunity for the men and women in attendance to have a look at each other. Such looks might later lead to the arrival of a poem by one of the men at attendance, which in turn might lead to a preliminary visit by him . . . and so forth. Excursions had many drawbacks, however, the main one being the bumpy ride in an ox cart traveling at about two miles per hour. Most women stayed at home most of the time. There, visits from men were another possibility for dealing with boredom.” [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Having an Affair in Heian Japan

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Suppose a man happened to notice the outline of a woman as she rode in a carriage, found the carriage particularly tasteful (carriages were status symbols and tools for displaying one’s tastes, like automobiles today might be), and thought he might like to meet her. He would find out where she lived and send a poem. Great care would go into this short three or so lines of verse. The handwriting must be perfect, of course. The content should convey the man’s intentions in an elegant, indirect way. The type of paper must be selected with care and perfumed with just the right scent. It must be folded properly and put into a tasteful envelope, to which a sprig of some tree branch or flower would be attached--which type would depend on season and circumstances. When the woman received the poem, all of these considerations and more would be on her mind as she tried to size up the man’s degree of refinement and good taste. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

"Lover's Surpised," late 1660s

“If she were unmarried, or married but lonesome and/or adventurous, and was duly impressed with the man’s poem, she might compose her own, suggesting that he pay a formal visit. Now she would carefully attend to all the matters described above in an attempt to impress him with her refinement and good taste. Attendants would announce the man’s arrival and lead him onto an exterior room where the woman would sit behind a screen. Ideally, the screen would be sufficiently thin that he could vaguely see her outline while sitting on the other side. Here, they would chat and perhaps exchange poems. Usually, that would be all. ~

“If both parties wanted to deepen the relationship, they would drop sufficient hints in the obligatory exchange of poems that would take place after the man’s visit. She might, for example, suggest he visit on a certain night. Assuming no significant complications, they would spend the night together. If others heard or saw him enter her chambers, they would probably pretend nothing had happened, but would gossip later. For real secrecy, a remote place away from the residence would be better. In any event, the man would leave with the rising sun, as was customary. As soon as he returned to his mansion, he would ordinarily a poem or letter, and she would reply. If he should fail to send one, or if his partner would not reply, this would be a definite sign the relationship was over, though being so blunt would suggest a lack of taste. Based on the poems and letters, the relationship would end or continue. ~

Sex in Heian-Era Japan

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: We have already seen something of the nature of relations between women and men from the passages above. Heian period aristocrats spent a great deal of time and energy pursuing romantic and sexual adventures. Virginity was not prized among either sex. Indeed, remaining a virgin for an unusually long time was a sure sign of possession by one or more demons. Sexual relations in the Heian period were a mixture of promiscuity and restraint, the restraint deriving not from moral codes or legal sanctions, but mainly from the demanding requirements of good taste. Outside of the romantic or sexual realm, men and women usually lived in different worlds and had relatively little direct contact--although we should remember that the romantic and sexual lives of Heian aristocrats were closely connected with other matters such as politics. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“What did they actually do while together? Of course, they had sexual intercourse at some point, but we know next to nothing about the details of sexual acts in mid-Heian times. Despite all the vast writing on the subject of romance and sex, the physical aspect of the act itself seemed to have attracted little attention or interest. Owing to the strong dislike of the nude body, we can probably guess that most couples had sex while still wearing at least some clothes. Beyond that, we can only imagine. It was the complex courtship rituals leading up to sex, the complex rituals following it, and the aesthetic experiences connected with it--but not the copulation itself--that Heian aristocrats found appealing. ~

“Here is Sei Shonagon’s idea of an undesirable partner for the night, from the chapter, "Hateful Things" in the Pillow Book: A lover who is leaving one at dawn announces that he has to find his fan and paper. 'I know I put them here somewhere last night,' he says. Since it is pitch dark, he gropes about the room bumping into the furniture and muttering, ‘strange! Where on earth can they be?' Finally he discovers the objects. He sticks the paper into the breast of his robe with a great rustling sound; then he snaps open his fan and starts flapping away with it. Only now is he ready to take his leave. What charmless behavior! 'Hateful' is really an understatement.”~

On the other hand, Sei also described her idea of the perfect lover. What follows is only the first of many paragraphs describing the (imagined) man’s actions in minute detail: “Being of an adventurous nature, he has still not married, and now at dawn he returns to his bachelor quarters, having spent the night in some amorous adventure. Though he still looks sleepy, he immediately draws his inkstone to him and, after having carefully rubbed some ink on it, starts to write his next-morning letter. He does not let his brush run down the paper in a careless scrawl, but puts himself heart and soul into the calligraphy. What a charming figure he makes as he sits there by himself in an easy posture, with his robe falling slightly open! It is a plain unlined robe of pure white, and over it he wears a cloak of yellow rose or crimson. As he finishes his letter, he notices that the white robe is still damp from the dew, and for a while he gazes at it fondly.” ~

“There is no description of this handsome, charming man’s physical body. The closest one gets is a description of his open robe. We find female authors describing handsome or ideal men frequently in Heian literature, and the descriptions are nearly all like that given here. It is important to keep things in perspective. Yes, sexual relations between men and women were relatively free at this time in Japan’s history compared with later ages or compared with certain other societies around the world at the same time. But the rules of taste imposed all manner of restrictions on personal behavior. Inappropriate sexual relations could lead to serious consequences such as a demotion in political office or even a period of exile outside the capital (a severe punishment for Heian aristocrats). Gossip about a woman’s sex life could eventually cause her such grief that she would become a Buddhist nun--or even commit suicide in extreme cases. Loneliness, jealousy, and insecurity were all part of the world of Heian-period romance sex, and women suffered more from these emotions than men owing to less mobility and other structural factors. For most of its inhabitants at least, the Heian capital was no sexual paradise.” ~

But in the eyes of some 20th century European historians, Heian-era Japan was a cesspool of promiscuity and vilness. In the 1930s. The Scottish minister, Reverend James Murdoch wrote: “Before a deftly turned Tanka [short poem], the tradition was that female coyness, if not chastity, was bound to yield as readily as the walls of Jericho fell flat before the blasts of the priestly trumpets and the shouts of the Israelitish people, while even the highest Ministers were apt to set infinitely more store by a reputation as an arbiter of taste in the world of belles-lettres and polite accomplishments than by renown as a great and successful administrator of the affairs of the nation... An ever-pullulating brood of greedy, needy, frivolous dilettanti--as often as not foully licentious, utterly effeminate, incapable of any worthy achievement, but withal the polished exponents of high breeding and correct 'form'. . . . Now and then a better man did emerge; but one just man is impotent to avert the doom of an intellectual Sodom. . . . A pretty showing, indeed, these pampered minions and bepowdered poetasters might be expected to make.”

"Visit by the Fan Salesman," Suzuki Harunobu, 1770

Hygiene in Heian-Era Japan

Japanese historian Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: Furthermore, the custom of bathing was not widespread among the nobility of that time. For one thing, there are no descriptions in Genji of eating or of bathing. Sei Shonagon wrote of the situation in which powder adhering to a woman’s neck, being red, floats up and stains the collar of her robe. In the summertime, the aristocrats might sprinkle water on themselves or wipe with wet towels, but especially in the winter, there was not custom of immersing one’s self in water. A steam bath was sometimes a treatment for illness, but their skin was dirty and smelly. [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits ++]

“This situation gave rise to mixed perfumes called takimono, but no mater which scents one blends into the mix, in the end, body odor and artificially-created scents co-exist. Although beyond the imagination of people today, if a Heian noblewoman were to approach you, her body odor would likely be powerful. Moreover, whenever they caught colds, they would chew on raw garlic, increasing the odor level even more. A passage in Genji clearly illustrates this point: a woman writing a reply to a man asks that he please not stop by tonight since she reeks from eating garlic. ++

“Please accept my apologies for discussing one unpleasant thing after another, but we can also suppose that the interior of the palace and the aristocrats’ rooms also smelled bad. The reason is that toilets were not in locations separated from the living areas. Instead, the aristocrats utilized rectangular “privy boxes” (boxes in which sand had been spread along the bottom) inside the rooms. On occasions such as winter nights, instead of taking the trouble to haul the boxes to the Kamo River for emptying, they would remain in the rooms. In such instances, should someone stop by for a visit, the house would probably smell bad despite setting out perfume.” ++

Education in Heian-Era Japan

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: With such a stress on writing and poetry, one might think that scholarship was an important part of the life of Heian aristocrats, as it would have been for their Tang and Song Chinese counterparts. In fact, however, this was not the case. Unlike their Chinese counterparts, Japanese aristocrats generally had little interest in moral philosophy or the systematic study of any body of theoretical knowledge. There was a central university, where Chinese classics formed the main curriculum. In the early Heian period, it was a significant institution, but by the end of the tenth century, increasingly fewer aristocrats studied there. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“There is evidence that elite aristocrats of the mid Heian period regarded its professors as laughably odd and out of place. In a passage from the Tale of Genji, for example, a number of young aristocrats cannot contain their laughter upon seeing a group of professors, clad in "ill-fitting robes," perform an induction ceremony at the university. Poetry, painting, music, calligraphy and the like comprised the educational training of most aristocrats, which private tutors usually directed. Men also had to learn classical Chinese composition, through which process they also gained a modest familiarity with the major works of Chinese literature such as the Confucian Analects. Some women also learned classical Chinese but they were under no social pressure to do so. ~

“Aristocratic education included some subjects that today we might find hard to imagine. Although in later ages, frequent bathing became part of Japanese culture at all levels, Heian nobles took baths only rarely. In such a context, perfume was an especially valuable commodity, liberally applied to mask odor. Perfume mixing, therefore, was an important aristocratic skill for men and women alike. Perfume making contests were common, and, in the Tale of Genji, Prince Genji was a skilled perfume mixer. Some common ingredients in perfumes of the time included aloes, cinnamon, ground conch shell, Indian resin, musk, sweet pine, tropical tulip, cloves, and white gum.” ~

Jogan Earthquake and Tsunami of A.D. 869

There was a great tsunami in A.D. 869. Generated by a quake known as Jogan, it struck the Sendai area and produced tsunami waves that reached almost two kilometers inland in an area just north of the present-day Fukushima nuclear power plant. According to Japan’s historical document, "Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku" ("The True History of Three Reigns of Japan"), compiled during the early Heian Period (794-1192), the Jogan Tsunami flooded inland areas more than three kilometers from shore and killed more than 1,000 people.

The Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku reads: “The lands of Mutsunokuni were severely jolted. The sea covered dozens, hundreds of blocks of land. About 1,000 people drowned...The sea soon rushed into the villages and towns, overwhelming a few hundred miles of land along the coast. There was scarcely any time for escape, though there were boats and the high ground just before them. In this way about 1,000 people were killed." Mutsunokuni is the name of the region that covered most of the present-day prefectures in the Tohoku region. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 12, 2011 /=/]

Since 1990, Tohoku Electric Power Co., Tohoku University and the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology have researched the traces left by the Jogan Earthquake. Their studies have shown that the ancient tsunami was on the same scale as that caused by the March 11 earthquake. The tsunami from Jogan earthquake left sand deposits miles inland. Based on sediments found in coastal areas from Miyagi Prefecture to Fukushima Prefecture thought to have been carried there by tsunami caused by the Jogan Earthquake, scientists estimated that the Jogan Earthquake had a magnitude of more than 8. /=/

According to the Active Fault and Earthquake Research Center the quake that caused the Jogan Tsunami made the fault slip more than seven meters. According to a report submitted by the national institute to the government in the spring of 2010, the Jogan Earthquake occurred off Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures and is estimated to have had a magnitude of about 8.3 or 8.4. The Jogan Earthquake tsunami penetrated more than four kilometers inland in the Sendai plain in Miyagi Prefecture, and about 1.5 kilometers inland in an area where Minami-Soma, Fukushima Prefecture, is currently located, the report said. According to a recent study conducted by Tohoku University, two tsunamiS equivalent to the size of the Jogan Earthquake tsunami have hit the Sendai plain in the past 3,000 years. /=/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016