WRITING IN THE HEIAN PERIOD

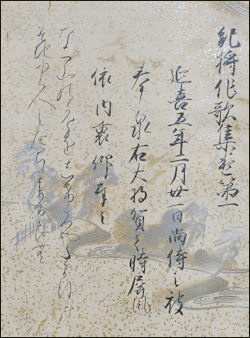

poetess Ukon

During the Heian period, Japanese script was developed. The complexity of Chinese writing and the fact that Chinese characters were often unsuited for certain Japanese sounds led writers and priests to work out two sets of syllabic systems based upon Chinese forms. By the middle of the Heian period these forms were unified and simplified into a writing form called kana. As the use of kana become widespread, it paved the way for the development of a unique Japanese literary styles.

There was great interest in graceful poetry and vernacular literature in the Heian period. Japanese writing had long depended on Chinese ideograms (kanji), but these were now supplemented by kana, two types of phonetic Japanese script: katakana, a mnemonic device using parts of Chinese ideograms; and hiragana, a cursive form of katakana writing and an art form in itself. Hiragana gave written expression to the spoken word and, with it, to the rise in Japan’s famous vernacular literature, much of it written by court women who had not been trained in Chinese as had their male counterparts. [Source: Library of Congress]

By the middle of the Heian period these phonetic alphabets, or kana as they are called, had been improved and brought into fairly wide use, opening the way for a literature of a pure Japanese style, which was to flourish in place of that in the imported Chinese idiom. Life in the capital was marked by great elegance and refinement. While the court gave itself up to the pursuit of the arts and social pleasures, its authority over the martial clans in the provinces became increasingly uncertain. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The development of the kana script encouraged literary production. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Kana is a simple alphabet (technically, a syllabary) consisting of approximately fifty characters. Two forms of kana developed, one straight and angular (similar to printed Roman script), the other a rounded, cursive style. Kana developed from Chinese characters. The cursive form of kana developed by writing the characters in a fast, abbreviated manner. Here are two examples. "Ho" derived from a cursive form of the Chinese character; "chi" derived from a cursive form of the Chinese character. The angular, "printed" style of kana derived from a single part of a Chinese character. For example, "ri" came from the right side of the Chinese character; "ho" came from the bottom right part of the Chinese character. Ordinary Japanese writing today involves a complex mixture of Chinese characters and the two forms of kana. Writing in Japanese was simpler in Heian times. Usually, it was all in kana, with perhaps just an occasional Chinese character here or there. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTOS VERSUS THE TAIRA CLAN IN THE HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD ARISTOCRATIC SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD LIFE factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN THE HEIAN PERIOD factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan TALE OF GENJI, MURASAKI SHIKIBU AND WOMEN IN THE STORY factsanddetails.com

Websites on Nara- and Heian-Period Japan: Essay on Nara and Heian Periods aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Nara Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the Heian Period Wikipedia ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji Temple Websites: Enryaku-ji Temple official site hieizan.or.jp; Marathon monks Lehigh.edu ; Tale of Genji Sites: The Tale of Genji.org (Good Site) taleofgenji.org ; Nara and Heian Art Sites at the Metropolitan Museum in New York metmuseum.org ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Tokyo National Museum www.tnm.jp/en ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Pillow Book” (Penguin Classics) by Sei Shonagon and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com; “The Tale of Genji” (Penguin Classics) by Royall Tyler and Murasaki Shikibu Amazon.com; “Emperor and Aristocracy in Heian Japan: 10th and 11th centuries” by Francine Herail and Wendy Cobcroft (2013) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 2: Heian Japan” by Donald H. Shively and William H. McCullough Amazon.com; “The Halo of Golden Light: Imperial Authority and Buddhist Ritual in Heian Japan” by Asuka Sango Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Japanese Arts of the Heian Period, 794-1185" by John M Rosenfield Amazon.com

Plate Dates Hiragana to 9th Century

In November 2012 the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Earthenware fragments from the late ninth century that bear hiragana calligraphy have been discovered in the ruins of the building of a noble who lived during the Heian period (794-1192) in Kyoto, the Kyoto City Archaeological Research Institute has announced. Modern hiragana is closer to the calligraphy on the discovered fragments than characters from the early 10th century that were believed to be the oldest, evidence that hiragana characters were created at least five decades earlier, the institute said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 30, 2012 +++]

The fragments were found at the ruins of the house of Minister Fujiwara Yoshimi (813-867) in November 2011. According to Kyoto University Prof. Ryohei Nishiyama, who analyzed the calligraphy, it can be read "Hitonikushito omoware." Hiroshi Sano, an associate professor of the university, explained it meant annoying yet adorable. The origin of hiragana was Manyogana, kanji that represented Japanese phonetically. Until now, hiragana was believed to have been established in the early 10th century, when an Imperial-commissioned poetry anthology, Kokin Wakashu, and diary Tosa Nikki, were compiled. +++

Importance of Handwriting in Heian-Era Japan

Heian-era poem

Handwriting was very important to aristocrats in Heian-Era Japan. The following excerpt from Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book, refers to Fujiwara no Nobutsune, an official in the Ministry of Ceremony: “One day when Nobutsune was serving as Intendant in the Office of Palace Works he sent a sketch to one of the craftsmen explaining how a certain piece of work should be done. 'Kindly execute it in this fashion,' he added in Chinese characters. I happened to notice the piece of paper and it was the most preposterous writing I had ever seen. Next to his message I wrote, 'If you do the work in this style, you will certainly produce something odd.' The document found its way to the Imperial apartments and everyone who saw it was greatly amused. Nobutsune was furious and after this held a grudge against me. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

In the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) there is a scene in which Prince Genji, the protagonist, and Lady Murasaki, Genji’s lover, are lying together in her room. Murasaki is worried because a thirteen-year-old princess, Nyosan, has recently become Genji’s official wife. While Genji and Murasaki are together, a letter from the young princess arrives. Murasaki is particularly anxious to see the handwriting, for this will determine the fate of all concerned. ~

When reading the letter, Genji allows Murasaki to catch a glimpse of it: “Murasaki’s first glance told her that it was indeed a childish production. She wondered how anyone could have reached such an age without developing a more polished style. But she pretended not to have noticed and made no comment. Genji also kept silent. If the letter had come from anyone else, he would certainly have whispered something about the writing, but he felt sorry for the girl and simply said [to Murasaki], 'Well now, you see that you have nothing to worry about.” The inference is that Genji would have nothing romantically to do with someone whose handwriting so substandard. Among the Heian aristocracy, handwriting was a direct extension of a person’s character, spirit and personality. Years later, when, presumably, her handwriting had improved, Genji starts up a relationship with the girl.

Importance of Poetry in Heian-Era Japan

Heian-era poem

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Heian aristocrats spent little time and energy writing scholarly essays and the like. The majority of what they wrote was poetry, and sometimes poems even substituted for memoranda in government offices. Nearly any event or occasion, public or private, called for rounds of poetry. A person deficient in poetic skills would have been at a serious disadvantage in Heian society. In their poems, the aristocrats delighted in obscure references and plays on words. Poetry was the ideal medium for communicating in a delicate, refined and indirect way. Taking a specific example, one night Murasaki Shikibu, author of the Tale of Genji, was awakened by a man tapping on the shutter of her bedroom — a sure sign of someone wanting to gain admittance. Suspecting who it might be, and wanting to have nothing to do with him, she lay still and did not respond. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

The next morning, she received the following poem (brought by messenger, as was typical) from the powerful and lecherous Fujiwara Michinaga, the man who had been tapping on the shutter the night before: How sad for him who stands the whole night long/ Knocking on your cedar door/ Tap-tap-tap like the cry of the kuina bird. The reply to such a poem should ideally follow up on the image presented in the initial verse, the kuina bird (a small water-rail) in this case. Murasaki answered: Sadder for her who had answered the kuina’s tap, / For it was no innocent bird who stood there knocking on the door.

Literature in Heian Period Japan

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: The Heian period was a time of great accomplishments in the literary arts. Murasaki Shikibu produced the world’s first novel, The Tale of Genji. Other aristocratic writers produced a wealth of prose and poetry, much of which has stood the test of time and remains great world literature, available in most major languages. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“Heian aristocratic literature was about the lifestyles and sensibilities of Heian aristocrats, particularly, of course, aristocratic women. This literature, whether poetry or prose, was concerned with aesthetics and taste, as we have already seen in a variety of contexts. But there was a darker side to Heian literature in the form of a deep-seated sense of anxiety. The cause of this anxiety was the impermanence (mujo) of the world. A sense of impermanence (mujokan) permeated much Heian-period literature, and aristocrats were especially aware of their own personal deterioration with age. ~

“Closely connected with this sense of impermanence was a poignant sense of the pathos associated with the transformation and passing away of things — blossoms, human beauty, life itself. This poignant sense of pathos is called mono no aware, which, coincidentally, might be rendered into a rough English translation as "an awareness of things" (mono = "thing[s]"). A sharp sensitivity to the impermanence of the world, and the anxiety that impermanence creates for humans, is a major characteristic of middle and late Heian-period literature.” ~

Women and Japanese Literature in the Heian Era

Tale of Genji paintting

Much of Japan’s famous vernacular literature was written by court women who had not been trained in Chinese as had their male counterparts. Three late tenth-century and early eleventh-century women presented their views of life and romance at the Heian court in Kagero nikki (The Gossamer Years) by "the mother of Michitsuna," Makura no soshi (The Pillow Book) by Sei Shonagon, and Genji monogatari (Tale of Genji) — the world’s first novel — by Murasaki Shikibu. Indigenous art also flourished under the Fujiwara after centuries of imitating Chinese forms. Vividly colored yamato-e (Japanese style) paintings of court life and stories about temples and shrines became common in the mid- and late Heian periods, setting patterns for Japanese art to this day. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “It was women who produced nearly all of this great literature. Most of the literature men produced was of mediocre quality and has long been forgotten. There is a clear reason for this quality gap. Men generally wrote literature in a foreign language, classical Chinese, of which the average aristocrat had a less than perfect grasp. Women, on the other hand, wrote literature in their native language. Men pompously wrote poor classical Chinese prose; women sat behind their screens and wrote great Japanese prose. When it came to poetry, men wrote in both Chinese and Japanese. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Literature and Buddhism in Heian Period Japan

The concern with impermanence and its implications found in Heian Period literature was a direct result of Buddhism. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Heian literature tends to reflect a general understanding of the basic teachings of Buddhism (recall, for example, the Four Noble Truths). Perhaps the best example of Buddhism in Heian literature is the Iroha poem, a verse that uses each of the kana one time. It was an aid for children in memorizing the kana but also contains a Buddhist message: “Though I smell the colorful blossoms, they are doomed to scatter /Who in this world exists forever?/ Today I cross over the deep mountains of existence/ I shall no longer dream shallow dreams, no longer be drunk. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Kobo Daishi

“The poem starts by establishing impermanence as the true state of the world and ends with the promise of enlightenment and transcendence of the cycle of willful existence (ui, the only Buddhist technical term in the poem). The colorful blossoms referred to in the poem are cherry blossoms, which became the most important metaphor in Heian-period literature (maple leaves in autumn were next in popularity). The cherry bursts forth in bloom during the spring, but the blossoms are fragile. Their peak of beauty lasts but two or three short days. At any time they are susceptible to being scattered by the wind, just as human life can end at any moment owing to disease or accident. Even under the best of circumstances, the flowers are all gone shortly after they begin to bloom. In the large picture, these frail blossoms last but for a brief moment. Cherry blossoms, and the feelings they invoked, became the ideal expression of mono no aware in literature. The second most common metaphor of impermanence was maple leaves in autumn. ~

“Incidentally, In the early Nara-period poetic anthology, Myriad Leaves, which is relatively (but not totally) free of Buddhist influence, the cherry was of little importance as a literal or metaphoric image. Instead, the pine and the plum reigned supreme. The pine is sturdy and green year-round. The white blossoms of the plum, which appear in the cold of February, are sturdy and long-lasting. The pine and plum stood for strength and longevity. ~

Here are two examples from Myriad Leaves of the pine and plum appearing as symbols of longevity and strength:

O Pine that stands

at the cavern’s entrance

looking at you

is like coming face to face

with the men of ancient times.

They say the plum flowers

blossom only to fall.

But not from the branch

I tie my marker to.

“The sentiments expressed in these poems are nearly the opposite of Buddhist teachings. In Heian times, although the plum and the pine continued to appear in poems, the Buddhistic cherry blossom took center stage. Here is a typical example from a collection of poetry called Kokin wakashu: “Indeed how they resemble this fleeting world of ours!/ The cherry blossoms./ No sooner do we gaze at them in bloom then they have scattered.

“The first word, utsusemi means both the human world and the empty shell of a cicada, thereby reinforcing the idea that this world is a transient place without permanence or substance — just like the cherry blossoms. Underneath the colorful, elaborate dress, the elegant cultural pursuits, the sex and romance, and other apparently pleasant aspects of life was an anxiety over the fact that none of it would last. The amorous, handsome Prince Genji, for example, eventually came to regret a life dissipated in the pursuit of empty pleasures. In a society so concerned with superficial appearances, growing old and losing one’s physical beauty became a particularly horrifying prospect. Throughout most of the Heian period, this sense of dread and anxiety was subtle. During the last century of the Heian period, and throughout the following Kamakura period, it became stronger and more overt.” ~

Tale of Genji

Tale of Genji

Tale of Genji is Japan’s most famous classical literary work. Regarded by some scholars as the world’s first important novel and the first psychological novel, it was written as an epic poem by Murasaki Shikibu (975-1014), a relatively low-ranked lady from the Japan Imperial court, between A.D. 1008-20. As a literary treasure Tale of Genji is to the Japanese what The Odyssey and The Iliad are to the West. It is written in episodes as if serialized in a magazine. It was written mostly in hiragana as women at the time were not supposed to learn kanji (Chinese characters).

Japanese historian Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: “If the longest selling book in the world were the Bible, in Japan it would surely be the Tale of Genji. Because it has hardly declined in popularity in the 1000 years since it was written, the Tale of Genji cannot be compared with Das Kapital [Marx’s Das Kapital is generally regarded as having been the best-selling book of the twentieth century]. Moreover, since the Meiji period, Genji has appeared in such derivative forms as stage performances, movies, and colloquial translations (and indeed, literary giants such as Yosano [Akiko], Tanizaki [Jun’ichiro], Funabashi, and Enchi [Fumiko] have all translated it into modern Japanese)...Consisting of roughly forty-five fascicles, it is truly worthy of a life’s work, with incomparable excellence in the quality of writing and overall sense, I agree with those who rate Genji as the best literary work. [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits ++]

The Tale of Genji story features an expressive narrative and a diverse cast of characters and is filled with details about court life in the mid Heian period and aesthetic pursuits that are still alive today: waka poetry, gakaku court music, noh and the tea ceremony. The main character, Prince Hikaru Genji, is believed to be modeled after Minamoto no Toru, a minister in the early Heian period (794-1192). Some see the novel as a moralistic tale because Prince Genji had an affair with his father’s mistress and was punished by having his own wife seduced by another man. Genji means the "shining one."

See Separate Article TALE OF GENJI, MURASAKI SHIKIBU AND WOMEN IN THE STORY factsanddetails.com

Decline of the Heian Sensibility

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Pressured by the Taira and by reduced revenues, the high courtly ideals of the middle Heian period began to decline, albeit gradually, in a variety of ways. In literature, for example, we see less concern with elegance and taste and increasingly detailed depictions of the more sinister sides of life. In a major novel from the twelfth century, Konjaku monogatari, for example, we find relatively graphic depictions of sexual acts, often with a sinister twist. In one part, a former lover turned demon has been having sexual relations with one of the emperor’s wives. The emperor called in Buddhist monks to perform an exorcism, but the demon merely bided his time, waiting a few months to make everyone think the exorcism had been successful. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Tale of Genji, scene from Chapter 34

Then one day the demon reappeared in the palace and: “... the lady reappeared following the demon. They made love right in front of the Emperor and everyone else present. It was so ugly an act that it cannot possibly be described. She performed it without any restraint at all. When the demon arose, she also stood up and went back into her room. The Emperor felt that there was nothing that could be done and collapsed in tears.” [Source: Shuichi Kato, A History of Japanese Literature 1: The First Thousand Years, New York, Kodansha International, 1979), p. 205.)

“Lady Murasaki and Sei Shonagon would have been shocked at such coarse, unpleasant matters depicted in literature. In the late Heian period, however, the "demons" (military families?) were gaining the upper hand over the "Emperor" (imperial court and aristocrats). The once-glorious aristocratic order (the imperial wife?) was clearly starting to decline by the twelfth century. ~

“Law and order also began to decline within the capital during the twelfth century. The great Buddhist temples surrounding Kyoto took advantage of the imperial court’s weakness by sending armed bands of warrior monks into the capital. These monks would sometimes march right up to the grounds of the imperial court and present lists of demands for political favors and concessions. To avoid attack from the imperial guards, the monks often brought various Buddhist icons, relics, and other holy objects with them. Terrified of divine wrath, the guards would not dare attack or even confront the monks (in most cases, there were some exceptions). The warrior monks' terrorizing of the capital and intimidation of the imperial court was another indication of the decline of late Heian period aristocratic society. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016