CHINESE MEDIA

All domestic media in China are owned by the state and remain strictly controlled by the government, with tight censorship rules in place. The news media in Communist China has traditionally focused on routine party meetings and activities and speeches of leaders. In recent years, there has been a call for it to report about topical social, economic, cultural and health issues. In some ways the media has responded as it has become more independent, the number of media outlets directly supported by the government has been reduced and some foreign investment in the media has occurred. On the difference between the media in China and Canada, one recent immigrant to Canada from China told AFP, the “media is different here. In China it is propaganda, promotion of things well done. Here they speak of disasters or human rights, look for negative sides.”

All domestic media in China are owned by the state and remain strictly controlled by the government, with tight censorship rules in place. The news media in Communist China has traditionally focused on routine party meetings and activities and speeches of leaders. In recent years, there has been a call for it to report about topical social, economic, cultural and health issues. In some ways the media has responded as it has become more independent, the number of media outlets directly supported by the government has been reduced and some foreign investment in the media has occurred. On the difference between the media in China and Canada, one recent immigrant to Canada from China told AFP, the “media is different here. In China it is propaganda, promotion of things well done. Here they speak of disasters or human rights, look for negative sides.”

China’s electronic mass media are regulated by the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA). Its main task is the administration and supervision of state-owned enterprises engaged in the television and radio industries. The Chinese Communist Party’s Propaganda Department traditionally has played a large role as arbiter of standards for appropriate broadcasts. The NRTA was formerly known as the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT, 1998–2013) and the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT, 2013–2018). It is a ministry-level executive agency controlled by the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It used to be a subordinate agency of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (formerly the Ministry of Information Industry).[Source: Library of Congress, Wikipedia]

Many Chinese now turn to the Internet for news rather than the traditional media. Some people still get their news the old-fashion, Communist way from notice boards which usually feature pages from the latest copy of the People's Daily as well as family planning posters, PLA recruiting notices and pictures of mutilated traffic accident victims, executed prisoners and people who blew themselves up playing with fireworks or dropping cigarettes at gas stations.

Chinese journalists often choose a pen name when they write something bearing state-sponsored ideology with which they (privately) disagree. But not just any pen name will do. A proper pseudonym gives the reader a tip off to the author’s dissenting opinion using coded language.

Since the early 1990s the media in China have become increasingly commercialized, producing massive growth in the cultural and entertainment industries. The number of media outlets in Beijing rose from 210 in 2004 to 356 in 2011. According to Routledge: "This evolution has also brought about fundamental changes in media behaviour and communication, and the enormous growth of entertainment culture and the extensive penetration of new media into the everyday lives of Chinese people." (See Book Below)

Sherly WuDunn of the New York Times won a Pulitzer prize for her work in China in the 1990s. Jaime FlorCruz has lived and worked in China since 1971. He studied Chinese history at Peking University (1977-81) and served as Time Magazine's Beijing correspondent and bureau chief (1982-2000). He also served as CNN’s Beijing Bureau Chief and correspondent.

See Separate Articles: TELEVISION AND MEDIA IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEWSPAPERS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MAGAZINES factsanddetails.com ; JOURNALISM IN CHINA: VIOLENCE, BRIBES AND LACK OF PRESS FREEDOMS factsanddetails.com ; CENSORSHIP AND STATE CONTROL OF THE CHINESE MEDIA factsanddetails.com ; FAKE NEWS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RADIO IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) MCLC ; China Media Project cmp.hku.hk ; China Digital Times chinadigitaltimes.net ; Television Stations chinese-school.netfirms.com ; CCTV english.cctv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Popular Media, Social Emotion and Public Discourse in Contemporary China By Shuyu Kong Amazon.com; “Media Politics in China: Improvising Power under Authoritarianism” by Maria Repnikova Amazon.com; “China's Media: In the Emerging World Order” by Hugo de Burgh Amazon.com; “Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis” by Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, Yin Hong, et al. Amazon.com; “The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media, and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Ya-Wen Lei Amazon.com; “Media in China, China in the Media: Processes, Strategies, Images, Identities” by Adina Zemanek Amazon.com; “Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Daniela Stockmann Amazon.com; News: “The End of Chinese Media: The "Southern Weekly" Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping's China” by Guan Jun, Kevin Carrico , et al. Amazon.com; “Trial By Media: Forced TV Confessions and the Expansion of Chinese Media” by Peter Dahlin Amazon.com; “Seeing: A Memoir of Truth and Courage from China's Most Influential Television Journalist” by Chai Jing, Cindy Kay, et al. Amazon.com;

History of the Press and Media in China

In the old days many people got information about the outside world from teahouse “news singers.” Suspicion of the media has a long history in China. In 1591, a Chinese border official complained of irresponsible “newspaper bureau entrepreneurs” who give no consideration to “matters of [national] emergency.”

Ting Ni wrote in the World Press Encyclopedia: “China's modern media, which were entirely transplanted from the West, did not take off until the 1890s. Most of China's first newspapers were run by foreigners, particularly missionaries and businessmen. Progressive young Chinese students who were introduced to Western journalism while studying abroad also imported the principles of objective reporting from the West. Upon returning home, these students introduced the methods of running Western-style newspapers to China. The May Fourth Movement in 1919, the first wave of intellectual liberation, witnessed the publishing of Chinese books on reporting, as well as the emergence of the first financially and politically independent newspapers in China. However, the burgeoning Chinese media were suffocated by Nationalist censorship in the 1930s. Soon after the Kuomintang (KMT) gained control of China in 1927, it promulgated a media policy aimed at enforcing strict censorship and intimidating the press into adhering to KMT doctrine. But despite brutal enforcement measures, the KMT had no organized system to rein in press freedom, and when times were good, it was fairly tolerant toward the media. The KMT gave less weight to ideology than the CCP eventually would and therefore allowed greater journalistic freedom. [Source: Ting Ni, World Press Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

On the foreign media coverage of China in the past. Paul French wrote: “Arguably, more column inches were devoted to China in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century than since. In 1928 the Sunday edition of the New York Times was running seven and sometimes eight columns of material on China from their correspondent Hallett Abend and sending urgent telegrams instructing him to send yet more China news. Starting around the time of the Boxers and the Siege of the Legations in 1900, the world’s public began to want significantly more information about China, and so the world’s great newspapers started sending and hiring full-time correspondents backed up by an army of stringers. Their numbers grew and then spurted in the 1920s.” [Source: “Foreign journalists in China, from the Opium Wars to Mao” by Paul French Danwei.org, June 19, 2009]

Chinese Media and Press in the Mao Era

Ting Ni wrote in the World Press Encyclopedia: “Chinese journalism under CCP leadership has gone through four phases of development. The first period started with the founding of New China in 1949 and ended in 1966, when the Cultural Revolution began. During those years, private ownership of newspapers was abolished, and the media was gradually turned into a party organ. Central manipulation of the media intensified during the utopian Great Leap Forward, wherein excessive emphasis on class position and the denunciation of objectivity produced distortions of reality. Millions of Chinese peasants starved to death partly as a result of media exaggeration of crop production. [Source: Ting Ni, World Press Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

“During the second phase (1966-78), journalism in China suffered even greater damage. In the years of the Cultural Revolution, almost all newspapers ceased publication except 43 party organs. All provincial CCP newspapers attempted to emulate the "correct" page layout of the People's Daily and most copied, on a daily basis, the lead story, second story, number of columns used by each story, total number of articles, and even the size of the typeface. In secret and after the Cultural Revolution, the public characterized the news reporting during the Cultural Revolution as "jia (false), da (exaggerated), and kong (empty)."

As a monopolistic regime, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is committed to the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist emphasis on the central control of the press as a tool for public education, propaganda, and mass mobilization. The entire operation of China's modern media is based upon the foundation of "mass line" governing theory, developed by China's paramount head of state, Mao Zedong. Such a theory, upon which China's entire political structure hinges, provides for government of the masses by leaders of the Communist Party, who are not elected by the people and therefore are not responsible to the people, but to the Party. When the theory is applied to journalism, the press becomes the means for top-down communication, a tool used by the Party to "educate" the masses and mobilize public will towards socialist progress. Thus the mass media are not allowed to report any aspect of the internal policy-making process, especially debates within the Party. Because they report only the implementation and impact of resulting policies, there is no concept of the people's right to influence policies. In this way, the Chinese press has been described as the "mouth and tongue" of the Party. By the same token, the media also act as the Party's eyes and ears. Externally, where the media fail to adequately provide the public with detailed, useful information, internally, within the Party bureaucracy, the media play a crucial role of intelligence gathering and communicating sensitive information to the central leadership. Therefore, instead of serving as an objective information source, the Chinese press functions as Party-policy announcer, ideological instructor, intelligence collector, and bureaucratic supervisor.

Media in the 1980s

Radio and television expanded rapidly in the 1980s as important means of mass communication and popular entertainment. By 1985 radio reached 75 percent of the population through 167 radio stations, 215 million radios, and a vast wired loudspeaker system. Television, growing at an even more rapid rate, reached two-thirds of the population through more than 104 stations (up from 52 in 1984 and 44 in 1983); an estimated 85 percent of the urban population had access to television. As radio and television stations grew, the content of the programming changed drastically from the political lectures and statistical lists of the previous period. Typical radio listening included soap operas based on popular novels and a variety of Chinese and foreign music. [Source: Library of Congress]

Radio and television expanded rapidly in the 1980s as important means of mass communication and popular entertainment. By 1985 radio reached 75 percent of the population through 167 radio stations, 215 million radios, and a vast wired loudspeaker system. Television, growing at an even more rapid rate, reached two-thirds of the population through more than 104 stations (up from 52 in 1984 and 44 in 1983); an estimated 85 percent of the urban population had access to television. As radio and television stations grew, the content of the programming changed drastically from the political lectures and statistical lists of the previous period. Typical radio listening included soap operas based on popular novels and a variety of Chinese and foreign music. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Most television shows were entertainment, including feature films, sports, drama, music, dance, and children's programming. In 1985 a survey of a typical week of television programming made by the Shanghai publication Wuxiandian Yu Dianshi (Journal of Radio and Television) revealed that more than half of the programming could be termed entertainment; education made up 24 percent of the remainder of the programming and news 15 percent. A wide cross section of international news was presented each evening. Most news broadcasts were borrowed from foreign news organizations, and a Chinese summary was dubbed over. China Central Television also contracted with several foreign broadcasters for entertainment programs. Between 1982 and 1985, six United States television companies signed agreements to provide American programs to China.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Press Encyclopedia: “The third phase of Communist China’s media development began in December 1978, when the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party convened. Deng Xiaoping's open-door policy brought about nation-wide reforms that nurtured an unprecedented media boom. The top agenda of media reform included the crusade for freedom of press, the call for representing the people, the construction of journalism laws, and the emergence of independent newspapers. Cuts in state subsidies and the rise of advertising and other forms of financing pointed the way toward greater economic independence, which in turn promoted editorial autonomy.

“The Tiananmen uprising in 1989 and its fallout marked the last phase. During the demonstrations, editors and journalists exerted a newly-found independence in reporting on events around them and joined in the public outcry for democracy and against official corruption, carrying banners reading "Don't believe us — we tell lies" while marching in demonstrations. The students' movement was suppressed by army tanks, and the political freedom of journalists also suffered a crippling setback. The central leadership accused the press of engaging in bourgeois activities such as reflecting mass opinion, maintaining surveillance on government, providing information, and covering entertainment. The once-hopeful discourse on journalism legislation and press freedom was immediately abolished. With the closing of the political door on media expansion, the post-Tiananmen era witnessed a dramatic turn towards economic incentives, allowing media commercialization to flourish while simultaneously restricting its freedom in political coverage. These developments produced "the mix of Party logic and market logic that is the defining feature of the Chinese news media system today."

Chinese Media in the 1990s and Early 2000s

Ting Ni wrote in World Press Encyclopedia, Media conglomerates emerged in the mid-1990s at provincial level and in major cities. These newspaper giants published books, magazines, audio-video materials and newspapers, and they run radio, TV stations, and Internet sites. As of the beginning of 2000, there were 15 media giants in China. The two reasons for the merger fever are media heads' frequent visits to their counterparts in Western countries and the desire to combat increasingly intense competition on China's media market. [Source: Ting Ni, World Press Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

In October 1997, the first English Edition Chinese newspaper, China Daily, Hong Kong Edition, was issued. In June 1998, the "three fixes" were implemented to streamline the administrative structure of the media and press. The three fixes mandate were: "1) fix the number of employees, 2) fix the workload and 3) fix the post."

In August 2000, China's first TV station, Sun TV, launched programming in Hong Kong. In January 2001, Shanghai began China's first digital TV program. Other cities, such as Shenzhen, Qingdao, and Hangzhou soon followed suit. In December 2001, the largest Chinese media, China Broadcasting and Television Group, was started in Beijing. In January 2002, China's Ministry of Radio, Film and Television and American Time and Warner started broadcasting CCTV English news (CCTV, Channel 9) 24 hours a day in New York, Houston, and San Francisco. In return, China allowed Time Warner's Mandarin programs (ETV) to broadcast in southeast China. This was the first foreign TV program to be shown in China.

Commercialization of the Chinese Media

China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 brought changes to Chinese media and publication businesses. According to the State Press and Publication Administration, within one year after joining WTO, China promised to allow foreign media to set up joint book and newspaper retail stores in five special economic zones and eight cities. Mergers also become increasingly prevalent in China's WTO era.

Christina Larson, a contributing editor at Foreign Policy, wrote on The Atlantic website: “ “In the past, the government fully subsidized all newspapers in China, from trade papers like Farmers Daily and Tourism Daily, to mainstream local and national newspapers, to English-language title newspaper, China Daily. Propaganda in the purest sense, the newspapers were free to entirely ignore their readers' preferences or opinions, printing only directives from central authorities.” [Source: Christina Larson, The Atlantic March 22, 2011]

“Then, in the early 2000s, in the midst of large-scale restructuring of many state-owned industries in China, Beijing took steps to partially wean papers from the government teat. A few new publications with private backing cropped up about this time, including the feisty news magazine Caijing. With less funding, some papers shrunk, but others opted “ for financial reasons “ to pay closer attention to what their readers wanted, hoping to sell more paid subscriptions and boost advertising.” Taking a more commercial approach in China has generally meant one of two things: more photos of semi-nude girls and sensationalized gossipy stories, or more insightful reporting and meaningful content.”

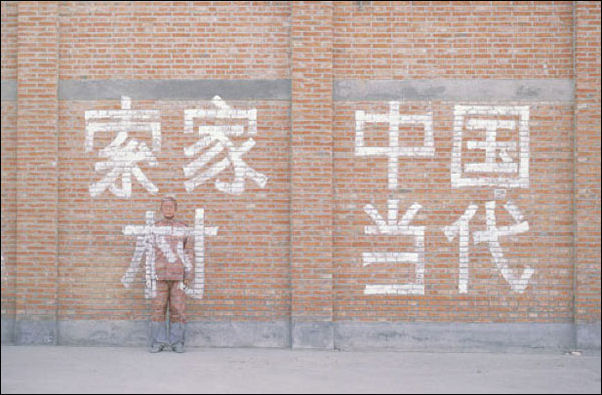

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Chinese Media More Open Than it Was

These days the media is certainly more open than it was in the Mao era. People can say things they couldn’t in the past and news source broach formally taboo subjects such a social unrest and industrial accidents. Newsstands are filled with glossy sports, entertainment and fashion magazines; the Internet contains a galaxy of stuff; and reporters are instrumental in uncovering corruption scandals and mining disasters. On television reports about agricultural production and revolutionary martyrs have been replaced by shows about couples who in fall in love and people who pursue dreams of being singing idols and tycoons

The openness and tolerance often applies more to superficial matters than controversial political and social issues. While newspapers and magazines have been allowed to become racier and publish more of sports and entertainment articles the government has made it clear it will not often tolerate stories on sensitive political topic such as corruption, police brutality or political reforms.

In the past when bad things happened the government’s instinctive reaction was to deny the things happened and then blame and vilify the accusers. In recent years the government has come to realize this strategy has limited benefits — especially with the Internet and cell phones getting the word out whether the government likes it or not — and is often more open and responsive when bad things occur: admitting mistakes, accepting responsibility, minimizing cover ups and outlining concrete responses.

China is worried about its international reputation especially with the international media unrelenting its reportage of unsafe toys, tainted food, collapsed bridges, mining disasters, choking smog, slave-like working conditions and cancer towns. The Chinese government has hired the public relations experts Edelman and Ogilvy and Washington lobbyist Patton Boggs to help improve its image.

Media and the Chinese Government

Matthias Niedenfuhr wrote in the Political Economy of Communication: “In the People’s Republic of China, the media industry has become increasingly commercialized over the past three decades, but like many other areas of the economy, it remains subject to the tensions between state and market priorities. In some aspects, market interests may seem to be in the ascendancy. Many programs and program formats, which for various political and social reasons would have been taboo” in the 1990s, “have been produced to meet market-led objectives. Nevertheless...authorities monitor and regulate media products to ensure that they do not stray beyond the parameters of acceptable political discourse. The state, therefore, remains the ultimate arbiter of what content reaches the audience.[Source: Matthias Niedenfuhr, Political Economy of Communication no. 1, 2013]

Historical television dramas “in particular provide an explicit example of a program format which is popular with audiences (and therefore revenue generating), but which is also profoundly affected by the political requirement to protect the past and present legitimacy of the Communist Party. The authorities adopt an adaptive — reactive approach, which combines formal regulation with ad hoc interventions to create an atmosphere of uncertainty and self-censorship among media producers.” Controversial programs often produce various rules and regulations which in turn shape the production of new content. “The institutional dynamics through which conflicting political and economic objectives have been negotiated in the media industry are reflective of a wider tug-of-war between state and market forces in China...It is difficult, however, to obtain information on policy principles and priorities in the PRC. Despite reform and opening, institutions in the Chinese party — state still operate in a rather opaque way and publicly available information in the sensitive area of media regulation is scarce.

In China, commercialization of the media “has only been partially realized — state funding has been reduced and operations have been commercialized, but state ownership and control over content have been retained. State interventionism is an anathema to transnational media conglomerates as well as supranational bodies such as the EU and WTO. However, the Chinese state keeps these players in check to prevent foreign entities from gaining too much influence in the domestic market.” China’s “media policy-making is dominated by state and party institutions, with a secondary role played by corporate interests and business associations. Only a marginal role can be attributed to voices in the public realm, such as academics, intellectuals, and netizens.

While adopting some elements of marketization, the Chinese authorities still strongly reject other elements, especially pluralistic ones. Central state and party institutions still effectively govern media policy. This selective adoption of market principles, while retaining central state interventionist principles, frequently leads to conflicts and paradoxes.

Yu Haiqing calls the Chinese case a ‘hybrid political-economic structure that is non-liberal, anti-liberal and neoliberal, all in one’. He notes that the Chinese media and communication industries are influenced by neoliberal strategies which seemingly conflict with “socialist legacies, traditional values, post-socialist dilemmas, and prosumer desires...This is the paradox of neoliberalism, or rather ‘disingenuous neoliberalism’, in China: a passion for intervention in the name of non-intervention, all in the name of ‘serving the people’ under the rubric of ‘ socialism with Chinese characteristics’. The market is not all free. It dances with the magic wands of both global capitalism and the Chinese authoritarian state...The news and current affairs sector is kept under tight state control while the entertainment business has become market-oriented:

Zhao Yuezhi defines these contradictory policy goals in the following way: The restructuring and rationalization of Chinas national media system under market logic has predominantly taken the form of bureaucratic monopoly capitalism. Under this system, media organizations under the control of the Party state, which had previously single-mindedly pursued ideological and cultural objectives, are now more or less in line with the capitalist system, assuming the twin objectives of capital accumulation and ideological legitimization .

Xinhua, China's Main News Agency

Xinhua (pronounced Shin-wa) means New China News Agency. It is the main news agency in China and is the largest and most influential media organization in China. Enjoying a monopolistic position as the only Chinese-Communist-Party (CCP)-mandated news agency in China, it is the largest news agency in the world as measured by the number of worldwide correspondents. Xinhua is a ministry-level institution subordinate to the State Council and is the highest ranking state media organ in China. [Source: Wikipedia]

Xinhua operates more than 170 foreign news bureaus worldwide and maintains 33 bureaus in China, one for each provincial administrative division. Xinhua is a publisher as well as a news agency, producing content in multiple languages and is a major vehicle for of information disseminated by the Chinese government and CCP. Its headquarters in Beijing is close to the central government's headquarters at Zhongnanhai.

China News Service (CNS) is the second largest state news agency in China, after Xinhua was formerly run by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, which was absorbed into the United Front Work Department of the Chinese Communist Party in 2018. Its operations have traditionally been directed at overseas Chinese worldwide and residents of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. The New China News Agency, the People's Daily, China News Agency and Guangming Daily are the main official news sources.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and his take on advertising

History of Xinhua

Xihua began as the Red China News Agency — the CCP’s original news agency — which was established on November 7, 1931. Six years later, it was changed its name to Xinhua. In the early days, the agency not only sent reports about China to the outside world but also used army radio to collect outside news, mainly dispatches of the Nationalist government's Central News Agency. These were edited and printed in Reference News, which was distributed to Party leaders. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Xinhua is also an intelligence gathering organization and has a long history of providing intelligence for high-level Party leaders. According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations: By the end of the 1980s, Xinhua had become the largest news organization, with three major departments: domestic with bureaus in all provinces; international with more than 100 foreign bureaus; and the General Office with both domestic and international news editing bureaus, sports news bureau, photo editing bureau, news information center and Internet center. As of 2001, it puts out almost forty dailies, weeklies, and monthlies. Its important subsidiaries include Zhongguo Zhengquan Bao (China Security), a daily that specializes in business news and the stock market, and Xinhua Meiri Dianxun (Xinhua Daily Telegraph), a general interest daily that carries the agency's own news dispatches.

“Although Xinhua belongs directly to the highest governmental body, the State Council, its daily operations rely heavily on instructions from various levels of the Party bureaucracy, from the Politburo to the central Propaganda Department. It has the largest and most articulated internal news system of any organization in China, which can be divided into three classes: secrecy, top secrecy, and absolute secrecy. It functions on a need-to-know basis. Those highest in the hierarchy get most fully briefed, while a stream trickles out to the lower level. The system creates a news privilege pyramid. The higher the privilege, the richer the news, the more comprehensive the secrets contained, and the more authoritative the ideas.

Xinhua’s Efforts to Expand Abroad

In 2007 Xinhua was given authority over foreign news agencies and was give the right to censor and edit the news of the foreign agencies. The move was widely seen as a blow to press freedom and an effort to help Xinhua dominate the Chinese news market. In 2010, Xinhua introduced a 24-hour English-language broadcast service, China Network Corporation, or CNC World, that aimed to reach 50 million viewers around the world. [Source: Stuart Elliott, New York Times, July 25, 2011]

In May 2011, Xinhua moved its North American headquarters from Woodside in Queens to a tower in Times Square, 1540 Broadway, at 45th Street. Xinhua also recently began aggressively marketing its news wire service, particularly in the developing world, with a goal of competing with news agencies like The Associated Press, Bloomberg News and Reuters. The Reuters building is at 3 Times Square, on Seventh Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets, and is decorated with huge video ad screens.)

Stuart Elliott wrote in the New York Times, “The expansion efforts by Xinhua are driven partly by a desire to counter what officials in the ruling Chinese Communist Party say is widespread bias against China in Western media reporting. The idea, Chinese leaders said, is to burnish the country’s image and give China a voice to match its newfound economic might. Many media analysts, however, are skeptical that Xinhua will make much headway anytime soon in markets like North America and Europe, where residents are sophisticated and often look askance at information delivered by news agencies owned by governments---any governments.

Advertising in China

According to the 2021 Dentsu Global Advertising Spend (Ad Spend) report, China was ranked the second biggest advertising market in the world after the U.S, with US$91 billion in ad revenues. Ad Spend (the amount of money spent on advertising for a product or activity) in China was expected to grow 8.5 percent in 2021, reaching US$111.6 billion, and growing 6.9 percent more in 2022. Simon Zhong, VP of Research and Data Analysis, dentsu Media, said "As China's economy continues to grow, we are observing signs of a rapid rebound in Advertising. The main drivers of this recovery are Internet services and the food and beverage sector, with spends in digital and outdoor media playing a huge role. [Source: Dentsu, July 12, 2021, Dentsu Inc. is a Japanese international advertising and public relations company]

According to the 2021 Dentsu Global Advertising Spend (Ad Spend) report, China was ranked the second biggest advertising market in the world after the U.S, with US$91 billion in ad revenues. Ad Spend (the amount of money spent on advertising for a product or activity) in China was expected to grow 8.5 percent in 2021, reaching US$111.6 billion, and growing 6.9 percent more in 2022. Simon Zhong, VP of Research and Data Analysis, dentsu Media, said "As China's economy continues to grow, we are observing signs of a rapid rebound in Advertising. The main drivers of this recovery are Internet services and the food and beverage sector, with spends in digital and outdoor media playing a huge role. [Source: Dentsu, July 12, 2021, Dentsu Inc. is a Japanese international advertising and public relations company]

Digital advertising represented 70 percent of the total ad spend in China, compared to 50 percent globally. According to iResearch's data, the size of China's online advertising market hit US$113 766.6 billion in 2020. This number does not match up with Dentsu data above, but what can you do. [Source: 2021 China’s Online Adverting Annual Report — Industry, iResearch, October 8, 2021]

China overtook Japan as the world’s second biggest advertising market after the United States in the late 2010s. The Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2014-18, published by global professional services network PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in 2014 compared consumer and advertising spending data from 54 countries across 13 sectors, including book publishing, filmed entertainment, internet advertising, music, radio, TV subscriptions and license fees, and video games. According to the survey, China’s entertainment and media market was forecast to grow from a value of US$127.34 billion in 2013 to US$213.55 billion in 2018. Overall, spending across the 13 sectors was expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.9 percent until 2018, compared with a global average CAGR across the sectors of 5 percent.Sectors with particularly high CAGRs include internet advertising (17.9 percent), internet access (13.7 percent), filmed entertainment (13 percent), and TV subscriptions and license fees (11.3 percent).

The biggest advertisers in China have traditionally are drug companies followed by cosmetic firms, retailers and service industries. The first television commercial in China was an advertisement for a tonic wine broadcast on a Shanghai television station in 1979.

Advertising revenues increased from $400 million in 1991 to $2.4 billion in 1994 to $10 billion in 2001. Growth in the early 2000s continuing at a blistering 40 percent rate, compared to 3 or 4 percent in the United States. In the 2000s, three percent of outdoor space, three percent of prime time television commercials and 10 percent of newspaper and magazines advertising were set aside for government propaganda. If media companies didn't comply with these quotas they risked losing their licenses that allow them to operate. In Shanghai alone three percent of outdoor space works out to 27 acres.

The world’s largest billboard space — measuring 300 meters by 45 meters —was erected along the Yangtze River in Chongqing and taken apart without ever attracting a single user. The problem was that the billboard was often shrouded in fog and no one could see it.

Difficulty Advertising Nationally in China

Advertisers have difficulty developing national marketing schemes in China because income levels, education levels and other demographics vary so much from place to place. One advertising researcher in the 2000s found though focus group studies that young people in Guangzhou are much more “pragmatic cool,” wanting their cell phones to have MP3 players, while than their counterparts in Shanghai who wanted an Ipod and a separate, trendy, cell phone. [Source: International Herald Tribune]

Advertisers aiming for a national market must at least develop copy in both Mandarin and Cantonese, and preferably other languages and dialects too. Even though Mandarin speakers outnumber Cantonese speakers by a 10 to 1 margin, Cantonese speakers in Guangdongand other southern cities tend to be significantly wealthier than Mandarin speakers.

The advertising market in China is divided into Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 3 and Tier 4 cities. The Tier 1 cities are Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Tier 2 cities include Chongqing, Harbin, Wuhan, Nanjing, Chengdu and Tianjin. Tier 3 and 4 cities often have populations of over a million people but possess names Westerners have never heard of. Thus far major western brands have had success in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities but have had difficulty penetrating Tier 3 and Tier 4 cities, which are dominated by Chinese brands.

With the help of Henry Kissinger, Gallup polls was allowed to open shop in China as a joint venture with a Chinese company. The polling company has been hired by U.S. chocolate producers, oil and electronics companies and Coca Cola to do marketing surveys but is not allowed to ask political questions.

Disrespectful Advertising and Chinese Control of Advertising

Advertisers have to answer to the Communist party. Coca-cola, for example, was forced to pull a multi-million dollar ad campaign with the popular Taiwanese singer A-Mei in 2000 because she sang the Taiwanese national anthem at the inauguration for a the Taiwanese president.

Advertisers have to answer to the Communist party. Coca-cola, for example, was forced to pull a multi-million dollar ad campaign with the popular Taiwanese singer A-Mei in 2000 because she sang the Taiwanese national anthem at the inauguration for a the Taiwanese president.

Government guidelines of advertisers include avoiding the use of superlatives like "best"when making comparisons to competitors; refraining from displaying flags and other national symbols; and following vague principals such as not "jeopardize the social order." Many foreign companies have had their ad rejected by censors for no clear reason with no explanation provided.

Ads that have been pulled have included Bufferin ads that claimed the headache medicine was best and Budweiser ads that claimed the beer was "America's favorite" (even though Budweiser had statistics to back up its claim). The anti-"best" guidelines were put in place to discourage exaggerated claims. The advertising industry is notorious for making false claims. In the past Chinese companies have claimed their tonics made people smarter and develop larger penises and their soaps have helped people lose weight.

Advertisers also have to abide by modesty rules. Models must cover the area between six inches below their necks and six inches above their knees. One shampoo commercial was pulled because it showed a woman's shoulder. Rebelliousness is also a no no.. A Pizza Hut showing a man standing on a table telling his friend how good his pizza tastes was pulled because standing on a table is considered rebellious. A Pepsi ad that showed Michael J. Fox scampering through traffic to get a can of Pepsi for an attractive neighbor was changed to show Fox stopping for a red light.

Tattoos and pierced ears are taboo. Anything that smack of individualism is frowned up. A Nike advertisement showing NBA star LeBron James defeating an animated martial arts master was banned because it was considered “disrespectful to Chinese traditional culture.” A Toyota ad that featuring an SUV cruising past kowtowing Chinese lions was yanked for the same reason.

Advertisements that promotes products by showing the how they increase one’s wealth and status seem to be do better in China than ones that show the pleasure the product will bring. One American advertising man told the Los Angeles Times, “Nothing is about feeling good or tasting good. Everything has to have a payoff.”

Fifty Chinese Celebrities Help Boost China’s Image Abroad

CCTV, the Xinhua news agency and China Daily have all made a great effort to increase their presence overseas. In 2009 alone, the central government spent US$6.6 billion to increase the international influence of the Xinhua News Agency, China Central Television (CCTV) and China Radio International (CRI). CCTV added a Russian-language service and an Arabic-language channel that reaches 300 million people in 22 countries. CRI can now be heard in 43 different languages, and Xinhua is adding 117 bureaus around the world.

In 2010, China’s State Council Information Office released a 30-second television commercial and a 15-minute promotional film aimed at polishing China’s global image. The first part, “People” featured 50 Chinese celebrities, including wealthy businessman Li Ka-Shing, basketball star Yao Ming, astronaut Yang Liwei, Olympic diving diva Guo Jingjing, film director John Woo, pianist Lang Lang. movie star Jackie Chan, Alibaba Group founder Jack Ma and actress Zhang Ziyi. [Source: Chang Ping, China Media Project, October 6, 2010]

The campaign was only one high profile example of China’s effort to sell its virtues to the rest of the world. In 2009 Chinese leaders welcome international media bigwigs such as News Corp chief Rupert Murdoch and the former British Broadcasting Cooperation's former executive, Richard Sambrook to the Great Hall of the People in Beijing for the first World Media Summit, dubbed the “Media Olympics”. [Source: Kent Ewing, Asian Times]

Image Sources: 1, 2) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3, 4) Censorship symbols, Human Rights Watch; 5) Hu Jintao, Wikipedia ; 6, 7, 8) Advertising, University of Washington ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022