FAKE NEWS IN CHINA

Chinese comic book In China, despite strict regulation of the media and internet, fake news, or what Chinese laws and domestic media often refer to as “rumors, ” appears to be permeating the internet and social media. Tencent, the operator of China’s biggest social media platform Wechat, released a report in January 2019 on its fight against rumors spread online. According to the report, Wechat intercepted over 84,000 rumors in 2018. The report said 3,994 anti-rumor articles were published through Wechat during the year by 774 entities, including the government internet information authority, the police, the food and drug administration, and state media, and the articles were read by 294 million users. Popular fake news topics include food safety, health care, and other social issues. [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, April 2019 |*|]

Internet regulators reportedly received 6.7 million reports of illegal and false information in a single month in July 2018, with many of the cases coming from Chinese social media platforms Weibo and WeChat. The government has been dealing with online misinformation since the spread of the internet in the late 2000s, and has launched a series of campaigns to combat online rumors. Various factors are propelling the phenomenon of the spread of misinformation in China, a Foreign Policy article argues, such as “a deep sense of societal insecurity, the increasing politicization and commercialization of information, and a craving for self-expression.” According to the article, “the party-led campaigns against rumors have been seen as attempts to take out potential critics and enemies. When the government labels something a rumor, that information comes to be seen not as fake but as something the government doesn’t want the public to know.”

David Bandursk of the China Media Project wrote: “Given the confusion of China’s press environment, where controls and propaganda crisscross with the worst commercial appetites and the best professional impulses, it is often difficult to tell which articles are real “fake news”, which are officially sanctioned falsehoods, and which are fake “fake news,” branded as such by government officials who have an active interest in suppressing the truth. “By some accounts, “fake news”, or “xujia xinwen” , has plagued news media in China since at least the Cultural Revolution, at which time media fabricated news to suit the political purposes of the Gang of Four. Chinese government officials, however, deny definitions of the term that lump in state propaganda, and the allegation of “fake news” can often signal action against news seen to violate propaganda restrictions — news, in other words, that is too true.” [Source: David Bandursk, China Media Project, January 27, 2011]

Over the past 30 years, "as economic reforms have moved rapidly ahead, the problem of “fake news” has certainly grown more serious. Many officials and academics point to the commercialization of media industry and intensified market competition as the root causes. But what about propaganda itself? It is not “fake news” when state media run news stories quoting rescued mine workers declaring as they emerge to safety: “Glory be to the Communist Party, glory be to the government, and glory be to the people!” In a highly commercialized media environment subject to strict propaganda controls, media find it safer and more profitable to avoid real public interest stories in favor of pleasant, harmless and salable falsehoods. Control, therefore, has played a central role in undermining truth and credibility, and is the soil that nurtures “fake news.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “Rumor in the Early Chinese Empires” (The Cambridge China Library) by Zongli Lu Amazon.com; “Translation, Disinformation, and Wuhan Diary: Anatomy of a Transpacific Cyber Campaign” by Michael Berry Amazon.com; “Fake News: Western Media’s Fabricated Reporting on China” by Maxime Vivas Amazon.com; News: “The End of Chinese Media: The "Southern Weekly" Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping's China” by Guan Jun, Kevin Carrico , et al. Amazon.com; “Trial By Media: Forced TV Confessions and the Expansion of Chinese Media” by Peter Dahlin Amazon.com; “Seeing: A Memoir of Truth and Courage from China's Most Influential Television Journalist” by Chai Jing, Cindy Kay, et al. Amazon.com; Miedia: “Popular Media, Social Emotion and Public Discourse in Contemporary China By Shuyu Kong Amazon.com; “Media Politics in China: Improvising Power under Authoritarianism” by Maria Repnikova Amazon.com; “China's Media: In the Emerging World Order” by Hugo de Burgh Amazon.com; “Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis” by Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, Yin Hong, et al. Amazon.com; “The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media, and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Ya-Wen Lei Amazon.com; “Media in China, China in the Media: Processes, Strategies, Images, Identities” by Adina Zemanek Amazon.com; “Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Daniela Stockmann Amazon.com;

Yu Hua on Rumors in China

What would constitute “fake news” in the West is often called “rumors” by the Chinese government. Sometimes there is a sliver of truth to them — even more. Often there is some sort of enemy to target to which the rumor is aimed, Yu Hua is an acclaimed Chinese writer. He wrote in the New York Times: Anywhere in the world it can be a challenge to sort fact from fiction on the Internet, but in China the problem has a unique dimension, given the relative absence of reliable information, especially on issues involving the government.[Source: Yu Hua, New York Times, January 7, 2014. Yu Hua is the author of “To Live,” “China in Ten Words” and other books. This article was translated by Allan Barr from Chinese.]

“In recent years, all too often the Chinese authorities have issued false statements in an effort to conceal the truth about matters of public concern, with the result that rumors thrive as people grope for clues about what really happened. As official lies and popular rumors vie for supremacy, it becomes all the harder to distinguish between fact and fiction, especially on the Internet. A key factor in this are the microblogs, which during the last four years have claimed a hold over Chinese society and are shaping people’s judgments. As a popular saying has it, “While truth is still tying its shoelaces, rumor has already run a whole lap around China.”

“But microblogs are simply a tool that makes it easy for rumors to circulate. It’s the falsehoods peddled for so long by the government that have fueled the rise of Internet gossip. On Feb. 6, 2012, Wang Lijun, then Chongqing’s police chief, sought refuge in the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu for a day. Officials in Chongqing cooked up a story that Mr. Wang was on sick leave, and rumors started to fly, one even announcing a coup d’état in Beijing.

“Government fabrications provoke people to search the Internet in an attempt to piece together the real story, and sometimes they find that things officials write off as rumor turn out to be true. For example, colorful details like Bo Xilai — Chongqing’s former top official who is serving time in prison for corruption — slapping Mr. Wang in the face were later confirmed as fact, making more people put their faith in rumors.

“Given the proliferation of rumors, and the speed at which they circulate online, the government realized that measures like deleting posts and shutting down microblog accounts had lost their effectiveness. So it began a campaign to prosecute bloggers. On Sept. 9, the Supreme People’s Court and Supreme People’s Procuratorate issued a ruling stipulating that defamatory reports, if reposted more than 500 times on the Internet, are a crime worthy of punishment.

Motorcycle Mama and Fake News

David Bandursk of the China Media Project wrote: “The first story to talk about — almost certainly an authentic piece of “fake news” — was a popular news story in the Chongqing Evening News last week about the saga of Li Chunfeng, a migrant worker in Zhejiang who reportedly drove a motorcycle 2,000 kilometers home to Chongqing after being seized with an irrepressible desire to see her six-year-old son. Seeing the story rising to the top at China’s leading online news site, QQ.com, we wrote on CMP Newswire last week that we suspected the story, which was drawing national attention and sympathy, was fake, and many Chinese journalists and readers have said the same since.” [Source: David Bandursk, China Media Project, January 27, 2011]

“The Chongqing Evening News story seems to play wantonly on popular sympathies ahead of the Chinese New Year, when millions of Chinese struggle to find their way back home to reunite with their families against the world’s biggest transportation logjam, when train and bus tickets are virtually impossible to buy. It tells how Li Chunfeng dreamt one evening in Zhejiang that her boy’s body was covered in blood and under attack by rats, so she decided the next day to make the long journey home on a motorbike she had purchased with an advance from her boss, disguising herself as a man for the sake of safety on the long journey.”

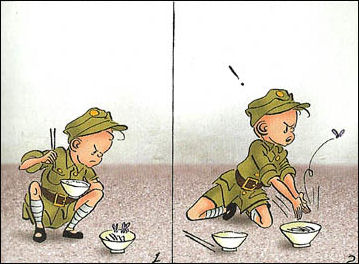

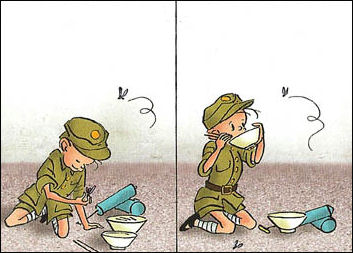

Sanmao comic “Li Chunfeng is the only source for this saccharine “news feature,” printed on a full page with two photos that look suspiciously posed, including one taken from the front as Li, with safety helmet on, rides a motorcycle with a look of heartfelt determination. The story is too much, too over the top, and too thin on real facts and sources — despite the fact that it is apparently a concerted effort by a “reporter”, a “correspondent” and an “intern,” all of whom are credited in the byline.”

“The story instantly found a warm-hearted following among Chinese Internet users, who gave Li Chunfeng the affectionate name “Motorcycle Mama” . But doubts about the authenticity of the story were voiced just as quickly, as reported in this China National Radio story. Some asked, for example, whether it was humanly possible for anyone to survive six days on half a bottle of water, as the news story claimed Li had.”

“Before long Xi’an’s commercial Huashang Bao followed up on the story with Li Chunfeng herself and found that she was unable to confirm basic facts, such as exactly when she had set off on the journey and whether she had taken national roads or expressways. Li seemed able to recall only one or two specifics about the journey at all.”

Writing at Southern Metropolis Daily today, well-known journalist and blogger Wu Yue San Ren noted with good humor: "The story suspected of being fake news . . . told how a mother had driven her motorcycle 2,000 kilometers . . . and in her four days on the road slept only 6 hours and basically ate nothing. Of course, the greatest thing on earth is a mother’s love — but this greatness certainly doesn’t translate into superpowers. If this mother were truly a superhero, she would simply have flown home."

Western Fake News in Chinese Social Media

In February 2017, Wikipedia editors voted to ban the British tabloid the Daily Mail and its website as sources, based on the news group’s “poor fact checking, sensationalism, and flat-out fabrication,” which rendered its content “generally unreliable.” Ironically the Daily Mail, and sources like it, are often prime sources of content — and fake news and conspiracy theory — in China.

Fang Kecheng wrote in Sixth Tone: In March 2017, an article titled “Flock of Drug-Addicted Parrots Fight With Poppy Farmers” was upvoted more than 100,000 times on WeChat. The piece was a translation of another article that had appeared in the Daily Mail, which had republished a story put out by the Daily Mirror, a rival British tabloid. While the piece focused on a very real problem faced by Indian poppy farmers — that parrots routinely plunder their crops for food — its portrayal of an avian addiction epidemic was highly overblown and sensationalized. [Source: Fang Kecheng, Sixth Tone, April 17, 2017. Fang is a Ph.D. student in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and was formerly a journalist at the Southern Weekly newspaper]

““Man Who Leaked Hilary [Clinton]’s Emails Assassinated: Are They Killing People to Hide Information, or Is There Something Else Going On?” blared the headline of another translated article on Sohu, a Chinese search engine and news aggregator, after the fatal shooting of Democratic National Committee employee Seth Rich in July 2016. The piece, which suggested that Clinton could have been silencing those suspected of leaking emails, raised questions similar to those that appeared on right-wing conspiracy websites in the United States and elsewhere. Further Chinese-language articles included the sensational claims that former President Barack Obama would refuse to leave the White House if Donald Trump won the election — an article originally published last September by a satirical news site — and that WikiLeaks documents showed Clinton was selling weaponry to the Islamic State — a piece that was published in October by the widely discredited right-wing site Political Insider.

“These articles — read by millions of Chinese Internet users — are only the tip of an increasingly disconcerting iceberg. To be sure, the Daily Mail and American right-wing conspiracy websites are” for the most part “not operating Chinese-language outlets in China.,,,The real force behind the massive importing from the Daily Mail and other such outlets stories is an influential — some might say notorious — group of social media accounts known as yingxiao hao, or “marketing accounts.” These accounts are mostly run by start-up companies with a low number of staff. Due to constraints on time and labor power, they seldom produce original content or check their facts. Instead, they adopt a cost-efficient approach toward content production. Nearly every article they publish is translated and revised based on eye-catching stories in the Western media — usually tabloids, clickbait websites, and fake news sites. They don’t have permission to reproduce copyrighted content, but this doesn’t stop them from doing so on a vast scale, since it’s very difficult for Western media to track copyright infringement in another language.

“Successful marketing accounts accumulate multitudes of followers from the content they share. As they do so, they start to advertise. Some of them even succeed in securing venture capital. For marketing accounts, traffic is everything, and quality and truth are nothing. That’s why they overwhelmingly choose to import sensational, controversial, or conspiratorial content from the likes of the Daily Mail and Political Insider, rather than from more serious and reputable sources. Even when they do import stories from, say, The New York Times or The Washington Post, they put a tabloid-esque spin on them, distorting their information.

“The commercial success of marketing accounts is facilitated by myriad factors, including other social media platforms also eager to increase traffic. The language barrier and the difficulty in accessing foreign news websites also help marketing accounts, whose readers are less likely to verify the information they read. Although some people in China are introducing fact-checking labels to fight the plague of fake news, their accounts carry much less influence than marketing accounts.

Real News Being Labeled as Fake News as Political Tool

“Unfortunately, we also have this week an example of “fake news” being used as a tool of political control,” David Bandursk of the China Media Project wrote, “We learn from Chinese-language reports by Deutsche Welle and Radio France International, since confirmed by numerous Chinese journalists and activists writing on Twitter, that Chengdu Commercial Daily reporter Long Can was dismissed on January 21 for “serious violations” and “false reports,” or “baodao shishi” .” [Source: David Bandursk, China Media Project, January 27, 2011]

“Sichuan-based blogger Song Shinan reported on Twitter that the Central Propaganda Department had ruled as “fake news” Long Can’s December investigation for Chengdu Commercial Daily into the rescue of 18 students from Shanghai’s Fudan University who had hiked into a rugged mountainous area near China’s scenic Huangshan, a rescue that led to the death of a police officer.”

“For much of December, popular anger in China focused on the Fudan University students. Many said their recklessness and insufficient preparation had put the local police rescue team in a dangerous position. Long’s report revealed that local police in Huangshan had ignored three emergency calls to “110" by student Shi Chengzu earlier in the day. Receiving no response from local authorities, the students contacted “Number Two Uncle”, a relative of one of the students many have speculated is an influential Shanghai official.”

“Once contact with “Number Two Uncle” was made, authorities in both Shanghai and Anhui sprang into action. The local mayor, propaganda chief and police chief of Huangshan all joined the rescue, according to Long’s report. By this time night was falling on Huangshan and conditions were treacherous, but Shanghai officials reportedly said that “rescue must be made whatever the cost.”

Deutsche Welle reported that China’s General Administration of Press and Publications (GAPP) subjected Long’s report to its own investigation under pressure from the Central Propaganda Department and unspecified official pressure in Shanghai (“Number Two Uncle”. GAPP then meted out the following punishment for Chengdu Commercial Daily: “1. journalist Long Can to be dismissed; 2. editor Zhang Feng to be fined 1,000 yuan; 3. executive editor Xu Jian to be dismissed; 4. head of the news desk, Zeng Xi , to be dismissed; 5. Zhang Quanhong , editorial board member in charge of the news desk, to be suspended from duties and subjected to severe examination; 6. editorial board member on duty that day, Wang Qi , to be fined 3,000 yuan; 7. chief editor Chen Shuping to be fined 3,000 yuan."

Long Can has insisted he told the truth and has complained vehemently about his unfair treatment. According to the RFI report in question, Shanghai police criticized Long Can’s investigative report on the Huangshan rescue, saying they had never received a report from a “so-called influential person” related to the trapped hikers. In any case Bandursk wrote, “The specific issues with Long’s report and the reasons why he and others have suffered as a result are not open for discussion in China. Long’s career as a professional journalist is almost certainly over, and a tragedy that is all too real hides behind an unsupported accusation of “fake news.”

Hitler Rumors and Praise in China

Kung Hsiang-hsi, Chinese banker and politician

and husband of the oldest Soong sister, with Hitler in 1936 In the early 2010s, several Chinese blogger openly praised and expressed of support for Hitler. In 2011 Richard Komaiko wrote in the Asia Times. “A rumor is spreading virally throughout the Middle Kingdom that asserts that Austrian-born Hitler was raised by a family of Chinese expats living in Vienna. According to the rumors, a family named Zhang found young Adolf - born on April 20, 1889, when he fell on hard times as a young man in Vienna.”[Source: Richard Komaiko, Asia Times May 25, 2011]

“They took him in, sheltered him, fed him and paid for his tuition. As a result of this assistance, Hitler held eternal gratitude and admiration for the Chinese people. The rumor also asserts that Hitler secretly supported China in World War II, and that his ultimate ambition was to conquer the world in order to share power with China, with everything west of Pakistan to be administered by the Fuhrer, and everything east of Pakistan the province of the Chinese people.”

This rumor apparently resonates deeply with the Chinese Internet generation. On May 10, 2011, a user of Kaixin, the Chinese equivalent of Facebook, posted a version of the rumor on his wall. The post attracted an enormous following, with more than 170,000 views and 40,000 comments. Of the people who left comments, 38.8 percent believe that Hitler was raised by Chinese, 7.1 percent believe that Hitler supported China in World War II, 4.6 percent regard Hitler as a hero, and 9.1 percent hope that China will have a leader similar to Hitler.

As the rumor spreads throughout the Chinese social web, admiration for Hitler is growing stronger and stronger. Blog posts with titles like "Why I like Hitler" are popping up every day, and an increasingly greater share of young Chinese are choosing to express their nationalism by voicing support for Hitler.

The reality wrote is that “Hitler’s years alone in Vienna are detailed in Chapter II of his memoirs, Mein Kampf. Nowhere in the chapter is there any mention of a Chinese family. The word "China" doesn't even appear in the text, nor do the words "Chinese", "Zhang" or "Cheung". There is absolutely no indication that Hitler had any meaningful contact with Chinese people in his youth. Hitler did not admire Chinese people. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Hitler regarded Chinese as an inferior race. Many Chinese bloggers are quick to point out that Hitler once said, "The Chinese people are not the same as the Huns and Tartars, who dressed in leather, they are a special race; they are a civilized race."

Top 10 Fabricated News of 2010 According to Global Times

1) A writers' conference in the presidential suite The Chinese Writers' Association (CWA) held a conference at the Hotel Sofitel in Chongqing from March 30 to April 2, 2010. On March 30, the West China City Daily (WCCD) published a brief in its entertainment section concerning a meeting of the CWA then underway in Chongqing. The single-paragraph article reported that delegates were staying in the presidential suite of a five-star hotel, feasting at a cost of 2,000 yuan ($304) per table, and shuttling around the city in Audis. The CWA fought back with a document from the hotel certifying that no one had stayed in the presidential suite and that all delegates had eaten at the standard hotel buffet during March 30 to April 4, when the meetings were being held (oddly, the certificate itself was dated April 2), and fired off an angry letter to the WCCD. The WCCD gave a letter of apology to the CWA on April 1, 2010. [Source: Global Times, January 25, 2011]

2) 2.2 million children died from indoor pollution each year A report published on May 17, 2010 by the China News Service said a study conducted by a health guidance center for the youth under the Standardization Administration showed that 2.2 million children die from respiratory illnesses every year in China. The Xinhua News Agency reported that it was an air filter manufacturer who released the misinformation. The air filter was developed by the Institute of Environmental Health and Related Product Safety. A worker at the Standardization Administration told the Global Times that a health guidance center for youth does not exist. And statistics from the World Health Organization show that the number of annual deaths from indoor air pollution is about 2.6 million globally.

3) Girl squeezed into pregnancy at Shanghai Expo. A young woman is said to have become pregnant after being raped at the Shanghai World Expo, reported by the Xinmin Evening News. The news spread like wildfire on many social-networking platforms. The victim, He Ting (pseudonym), had been raped while trapped in a huge crowd trying to get a ticket to watch a performance by a South Korean band on May 30, her mother was quoted as saying. The rape last only seconds, leaving the girl no time to scream for help, the stories said. However, police later said there had been no claim of rape as described in the story and no report of the story by the newspaper. It also said the names of the two reporters had been made up.

4) Online game "Stealing Vegetables" to be banned. The Ministry of Culture denied they are thinking about banning the popular online interactive game "Stealing Vegetables" after a controversy on October, 2010. An official surnamed Li from the ministry said they were studying whether the game produces any harmful impact before they consider changing or banning it, the Gansu-based Western Economic Daily said. "Stealing Vegetables" gained popularity among office workers in 2009.

Fake Prostitute's Microblog

Sanmao comic In September 2011, China National News reported: “China's popular microblog service provider Thursday permanently deleted the account of a self-proclaimed 'high-profile' female prostitute who was later discovered by police to be a 31-year-old man seeking online fame. Sina.com, the company that hosts the popular Weibo microblogging service, also suspended the accounts of six other users for two weeks for spreading rumours regarding the supposed prostitute, reported Xinhua. [Source: China National News, September 29, 2011]

Using the pseudonym 'Ruoxiaoan1', Lin posted 401 entries on his Weibo account starting from January, fabricating stories about working as a female prostitute in Hangzhou, the capital city of east China's Zhejiang province. On his microblog, Lin depicted himself as a 22-year-old woman who 'accidentally' lost her virginity and became a sex worker. His microblog account was followed by more than 250,000 users, including several prominent Chinese Internet celebrities. Some of his entries were reposted as many as 10,000 times.

Police said Lin took cues from foreign literature while writing his 'prostitute diary' in order to attract attention from netizens. Lin was fined 500 yuan ($78.5) in accordance with China's Internet regulations for disturbing public order. Lin apologized for his actions, police said.

Response to Fake News

In November 2011 there were multiple articles in official Chinese media about the importance of the proper handling of microblogs and the dangers of Internet rumors,” Bill Bishop, an American blogger living in Beijing, wrote on his blog DigiCha. One of the primary objectives of the articles was brining attention to stamping out so-called “fake news,” many regard as a rapidly metastasizing social ill.”

First, [fake news] has spread from commercialized, metro media to traditional authoritative [Party] media. Second, it has spread from entertainment and social news to economic and political news. Third, as traditional and internet-based media have had a more interactive relationship, fake news has been transmitted much more rapidly and widely. Fourth, there has been a trend from simple concocting of fake news to making idle reports, reporting gossip, exaggerating, going against common knowledge and other such issues, which have steadily spread. [Source: J. David Goodman, New York Times, December 5, 2011]

Mr. Bishop, the blogger, highlighted two recent articles — one in Xinhua, the other in The People’s Daily, China’s official newspaper — where Internet rumors are likened with illegal drugs. “The article states that “Internet rumors are “societal drugs” — which are no less harmful to society than Internet pornography, gambling or drugs,” he said of the piece in The People’s Daily. “The comparisons to drugs and drug dealing, sometimes a capital offense in China, may be a sign of an impending harsh crackdown on those who spread Internet rumors,” he said.

Faked Photo Incites Mockery

Sanmao comic Peter Walker wrote in The Guardian, “For government officials in Huili, a distinctly modest county in a rural corner of south-west China, attracting national media coverage would normally seem a dream come true. Unfortunately, their moment in the spotlight was not so welcome: mass ridicule over what may well be one of the worst-doctored photographs in internet history.” [Source: Peter Walker, The Guardian June 29, 2011]

The saga began on Monday when Huili's website published a picture showing, according to the accompanying story, three local officials inspecting a newly completed road construction project this month. The picture certainly portrayed the men, and the road, but the officials appeared to be levitating several inches above the tarmac. As photographic fakery goes it was astonishingly clumsy.

The outraged — or amused — calls began to the county's PR department, which immediately apologised and withdrew the image. The explanation was almost as curious as the picture itself: as other photos showed, the three men did visit the road in question, but an unnamed photographer decided his original pictures were not suitably impressive and decided to stitch two together. "A government employee posted the edited picture out of error... The county government understands the wide attention, and hope to apologise for and clarify the matter," a Huili official told the state-run Xinhua news agency.

Officials from the county, in Sichuan province, even hurriedly signed up to the hugely popular Sina Weibo social media site to post an explanation. All this was, however, too late to prevent a torrent of mockery as the offending image was passed around chatrooms and other websites. Inevitably, within hours there was a flood of parodies showing the officials variously landing on the moon, surrounded by dinosaurs and, in one instance, joined on their inspection tour by the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il.

Mystery Crash Leads to Online Ban of “Ferrari” in China

One of the most famous rumor-spawning events in China has the crash of a red Ferrari in 2012 that occurred at the same time controversial politiian Bo Xilai was being ousted from the high ranks of the Chinese Communist Party. Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: “Censors in China have excised the word Ferrari from the country's biggest social networking sites in an attempt to suppress all public discussion of a sensitive mystery car crash. The ban followed a burst of speculation that the young driver killed in the high-speed accident may have been the son of a senior Communist Party official, thus raising awkward questions about how a civil servant could afford to buy his offspring one of the world's most desirable and expensive cars. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, March 20, 2012]

China's internet censors have a number of ways of banning particular words or phrases from Sina Weibo and other microblogging sites. The simplest and most regularly used method is to remove the offending term from the site's internal search engine. A more extreme tactic - and the one used in the case of Ferrari - automatically removes any post containing that word. Hints at the extreme political sensitivities surrounding the crash emerged as other words and names joined the list of banned words while newspaper reporters revealed that they had been forbidden from investigating or writing about the crash.

A brief local newspaper report on the crash, which occurred shortly after 4am on Sunday in Beijing and apparently involved a Ferrari F430, was swiftly removed from the website. The ban was imposed with the ruling Communist Party in the throes of its most public political turmoil for more than 20 years after the downfall of Bo Xilai. Internet censors have been busy since the sacking of Bo Xilai as party boss of the sprawling city of Chongqing. His name and those of other family members have been blocked as search items. The Government appears especially keen to snuff out speculation about Mr Bo amid reports that he may be under house arrest pending a fuller investigation of his conduct. Mr Bo has his own Ferrari link: he recently dismissed as nonsense that his Harrow and Oxford-educated son, Bo Guagua, drove a red Ferrari.

The exact circumstances of Sunday's crash, beyond the fact that pictures of the twisted wreckage clearly showed it was a black Ferrari, are unclear. The driver, thought to have been in his 20s, was travelling with two young women sharing the single passenger seat. They reportedly survived the crash but with severe injuries. The was even some speculation that Bo Xilai’s some was behind the crash even though he was in the United States at the time.

Combating Fake News in China

Spreading fake news that seriously disturbs public order through an information network or other media is a crime under China’s Criminal Law and is punishable by up to seven years in prison. The 2016 Cybersecurity Law prohibits manufacturing or spreading fake news online that disturbs the economic and social order. The Law also requires service providers, when providing services of information publication or instant messaging, to ask the users to register their real names. [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, April 2019,|*|]

According to the rules on internet news information services issued by the Cyberspace Administration of China, entities providing such services must obtain a license. When reprinting news, internet news information service providers may only reprint what has been released by certain news organizations prescribed by the state. The service providers and users are prohibited from producing, reproducing, publishing, or spreading information content prohibited by laws and administrative regulations. Once service providers find any prohibited content, they must immediately stop transmitting the information, delete the information, keep the relevant records, and report the matter to competent government authorities. |*|

In an effort to fight fake news, in 2018, China launched a platform named “Piyao” — a Chinese word meaning “refuting rumors.” The platform, which also has a mobile app and social media accounts, broadcasts “real” news sourced from state-owned media, party-controlled local newspapers, and various government agencies. |*|

The spreading of fake news may not simply be due to the availability of technologies to circulate it. A Foreign Policy article points out that, in China, there are other factors propelling the phenomenon: a deep sense of societal insecurity, the increasing politicization and commercialization of information, and a craving for self-expression. The article argues that, “the party-led campaigns against rumors have been seen as attempts to take out potential critics and enemies. When the government labels something a rumor, that information comes to be seen not as fake but as something the government doesn’t want the public to know.”

Chinese Laws Aimed at Fake News

Sanmao comic

On August 29, 2015, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) — one of the highest adopted the Ninth Amendment to the People's Republic of China (PRC) Criminal Law. The Amendment added into the Law the crime of spreading false information that seriously disturbs the public order through an information network or other media. This offense is punishable by up to seven years in prison. [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports April 2019 |*|]

The Ninth Amendment added a paragraph to article 291a of the Criminal Law, stating that: whoever fabricates false information on [a] dangerous situation, epidemic situation, disaster situation or alert situation and disseminates such information via [an] information network or any other media, or intentionally disseminates [the] above information while clearly knowing that it is fabricated, thereby seriously disturbing public order, shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years, criminal detention or public surveillance; if the consequences are serious, he shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not less than three years but not more than seven years. |*|

Chinese law prohibits any online publication and transmission of false information that may disrupt the economic or social order. The law also bans other information, such as information that may endanger national security, overturn the socialist system, or infringe on the reputation of others. Spreading false information that seriously disturbs public order through an information network or other media is a crime punishable by up to seven years in prison. |*|

Network operators are obligated to monitor the information disseminated by their users. Once a network operator discovers any information that is prohibited by law or regulation, it must immediately stop the transmission of such information, delete it, take measures to prevent it from proliferating, keep relevant records, and report to the competent government authority. |*|

Social media platforms must maintain a license to operate businesses in China. Users are also required to register their real names and other identity information with service providers. Also, specific rules regulating internet news information services have been established. For example, when reprinting news, internet news information service providers may only reprint what has been released by official state or provincial news organizations, or other news organizations prescribed by the state. |*|

The government has reportedly launched campaigns to combat online rumors by shutting down social media accounts, demanding that websites “rectify their wrongdoing, ” detaining those accused of manufacturing misinformation, and imposing penalties on dissenters and opinion leaders. In 2018, China launched a platform named “Piyao” — a Chinese word meaning “refuting rumors.” The platform, which also has a mobile app and social media accounts, broadcasts “real” news sourced from state-owned media, party-controlled local newspapers, and various government agencies. |*|

Methods Used to Combat Fake News in China

On the basis of the PRC Cybersecurity Law and the Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services, China’s central internet information authority, the Cyberspace Administration of China, issued the Provisions on Administration of Internet News Information Services on May 2, 2017. [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports April 2019]

1) License Control: Under the Provisions, any entities providing internet news information services to the public — whether through websites, apps, online forums, blogs, microblogs, social media public accounts, instant messaging tools, or live broadcasts — must obtain a license for internet news information services and operate within the scope of the activities sanctioned by the license. Such licenses are only issued to legal persons incorporated within the territory of the PRC, and the persons in charge and editors-in-chief must be Chinese citizens. Providing internet news information services without a proper license is punishable by a fine of 10,000 to 30,000 yuan (about US$1, 500 to $4, 500). |*|

2) Restrictions on Reprinting News: When reprinting news, internet news information service providers may only reprint what has been released by official state or provincial news organizations, or other news organizations prescribed by the state. The original sources, authors, titles, and editors must be indicated to ensure that the sources of the news are traceable. |State or local internet content authorities may issue a warning to violators of this provision, order them to rectify their wrongdoings, suspend their news services, or impose a fine of 5,000 to 30,000 yuan (about US$750 to $4, 500). Violators may also be criminally prosecuted, according to the Provisions. |*|

3) Prohibited Information: The Provisions also prohibit internet news information service providers and users from producing, reproducing, publishing, or spreading information content prohibited by applicable laws and administrative regulations. State or local internet content authorities may issue a warning to violators of this provision, order them to rectify their wrongdoings, suspend their news services, or impose a fine of 20,000 to 30,000 yuan (about US$3,000 to $4,500). Violators may also be criminally prosecuted, the Provisions state. |*|

). Obligations of Service Providers Once internet information service providers find any content prohibited by the Provisions or other laws and administrative regulations, they must immediately stop transmitting the information, delete the information, keep the relevant records, and report the matter to competent government authorities. The Provisions also repeat the requirement of real-name registration under the Cybersecurity Law, providing that internet news information service providers must ask users of the internet news information publication platform service to register their real names and provide other identity information. |*|

Violators of these provisions are punishable by the state or local internet information authority in accordance with the Cybersecurity Law. |*|

China Vows to Punish Posters of Internet Rumors

What would constitute “fake news” in the West is often called “rumors” by the Chinese government. Sometimes there is a sliver of truth to them — even more. In October 2011, Associated Press reported, “China is vowing anew to punish people who post rumors and falsehoods on the Internet as the government tries to rein in forums that have increasingly become sources of debate and criticism. A spokesperson for the State Internet Information Office, a regulatory body under China's Cabinet, said in a statement released late Friday that Internet rumors and hoaxes were "malignant tumors" that harm social stability. The unnamed spokesperson's statement, which was carried by the official Xinhua News Agency, called on Internet users to abide by laws and stop spreading rumors, and urged websites to up their policing of content. [Source: Associated Press, October 1, 2011]

Drawing the spokesperson's particular ire were the salacious, sarcastic postings on the popular Twitter-like Sina Weibo service that purported to be from a 22-year-old prostitute but were really posted by a 31-year-old male editor. Xinhua said the "prostitute's diary" account attracted more than 250,000 followers before the author's true identity was discovered and the account shut down.

Social media sites that are platforms for users to generate content are posing a challenge for China's authoritarian government, which is used to controlling what media tell people. After a crash on the showcase high-speed rail system in July, the government lost control of the message on the Internet, as people questioned, criticized and ridiculed the official response. Soon afterward, the government began issuing warnings about untrammeled speech on the Internet and the need for companies to remove "rumors" and "false news," which are widely seen as code words for criticisms. The spokesperson's statement ordered local authorities and websites to penalize offenders.

Under Chinese regulations, spreading rumors is punishable by five to 10 days in jail plus a 500 yuan ($80) fine. In March this year, a resident of the city of Hangzhou received the maximum penalty for warning people to stay away from seafood from eastern China because the seas were being contaminated by leaks from the Japanese nuclear power plant damaged by the earthquake and tsunami.

Twitter-like microblogs, which have about 200 million users in China, have come under particular scrutiny. After Sina Corp. received a pointed visit from a Politburo member, the company said it would freeze the accounts on its widely used Weibo service for a month of anyone found spreading rumors.

Image Sources: Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022