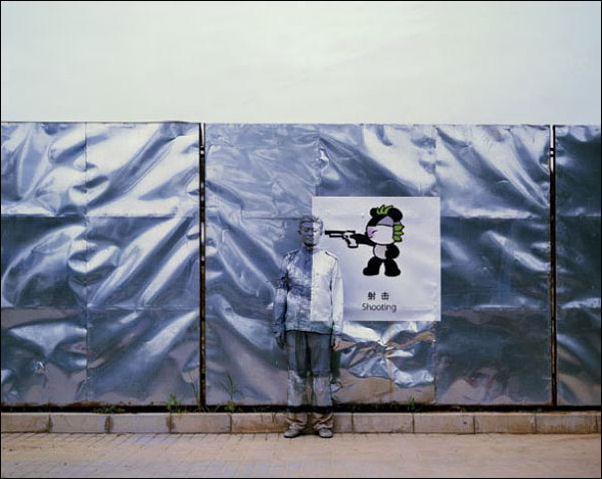

JOURNALISM IN CHINA

artist Liu Bolin preparing a piece Journalism is a vastly different concept in China, a country where free speech is fiercely quashed and propaganda the primary role of domestic newspapers and broadcasters. In China, which ranks among the top jailers of journalists in the world, the main media outlets, including Xinhua News Agency, were created to serve the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in whatever capacity possible.

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times,”In the past, China media followed a simple formula for covering international events: If bad things were happening in richer, developed countries, the story got big play. They especially relished the chance to showcase the messier side of democracy, with large, unflattering photographs whenever legislators in Taiwan or South Korea engaged in fisticuffs. Anything that threatened Beijing's diplomatic interests was ignored as much as possible.[Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 04, 2011]

In recent years the Chinese media has made an effort to be more current and relevant. "The Chinese press has been transformed in the last few years from a propaganda organ to covering real news. They are adopting the same techniques and standards as the Western press," Li Datong, a retired editor of the China Youth Daily's magazine supplement, told the Los Angeles Times. Ordinarily he is a vehement critic of the state media.

The Chinese government is making a big investment in its overseas media operations.. Both CCTV and the official New China News Agency are expanding English-language operations with the hope of putting Beijing's spin on the world's news. Still, the state media ultimately report to the Communist Party, and the intervention of censors is at times embarrassingly apparent. CCTV reporters have cut off by anchors during live reports for expressing things the government didn't like

See Separate Articles: TELEVISION AND MEDIA IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MEDIA: HISTORY, ADVERTISING, NEWS AND GOVERNMENT RELATIONS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEWSPAPERS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MAGAZINES factsanddetails.com ; CENSORSHIP AND STATE CONTROL OF THE CHINESE MEDIA factsanddetails.com ; FAKE NEWS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) MCLC ; China Media Project cmp.hku.hk ;China Digital Times chinadigitaltimes.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Popular Journalism in Contemporary China: Politics, Market, Culture and Technology”by Chengju Huang Amazon.com; “China's Unruly Journalists: How Committed Professionals are Changing the People’s Republic” by Jonathan Hassid Amazon.com; “The End of Chinese Media: The "Southern Weekly" Protests and the Fate of Civil Society in Xi Jinping's China” by Guan Jun, Kevin Carrico , et al. Amazon.com; “Trial By Media: Forced TV Confessions and the Expansion of Chinese Media” by Peter Dahlin Amazon.com; “Seeing: A Memoir of Truth and Courage from China's Most Influential Television Journalist” by Chai Jing, Cindy Kay, et al. Amazon.com; Miedia: “Popular Media, Social Emotion and Public Discourse in Contemporary China By Shuyu Kong Amazon.com; “Media Politics in China: Improvising Power under Authoritarianism” by Maria Repnikova Amazon.com; “China's Media: In the Emerging World Order” by Hugo de Burgh Amazon.com; “Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis” by Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, Yin Hong, et al. Amazon.com; “The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media, and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Ya-Wen Lei Amazon.com; “Media in China, China in the Media: Processes, Strategies, Images, Identities” by Adina Zemanek Amazon.com; “Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Daniela Stockmann Amazon.com;

Good News: Riots in London; Bad News: Arab Spring Protests

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2011: Perhaps not since the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 has there been as much international news so inherently threatening to the Chinese Communist Party. The strongmen with whom they did business in the Middle East are losing their jobs “ and nearly their heads. The U.S. debt crisis threatened more than $1 trillion of China's overseas investments. The London riots were a happier occasion for the press here. The state media had a good chuckle reporting British Prime Minister David Cameron's call to restrict social media after evidence emerged that rioters had used BlackBerrys to communicate.

Global Times, the nationalist newspaper closest to the Communist Party, had a field day with recent events. "A series of shocking incidents in Western countries, downgrading of U.S. credit rating, deteriorating European sovereign debt crisis, Norway's gun-shooting tragedy, large-scale street turmoil in the U.K., all show that the West is experiencing a deep systematic crisis under the heavy impact of the international financial crisis," read an editorial in Friday's paper. "Defects of the West's economic and political systems have been fully exposed."

The Arab Spring Protest proved to be too big to tune out. Not that the state media didn't try: At the outset, they downplayed the revolt against Egypt's Hosni Mubarak, portraying protesters as hooligans and looters and praising Mubarak's efforts to "maintain stability." Up until 24 hours before Mubarak resigned, the Cairo correspondent of China's CCTV was declaring on air that CNN and BBC were wrong and that Mubarak would survive. By the time it was Moammar Kadafi's turn, notwithstanding China's economic ties to Libya, CCTV journalists were out in the trenches with the rest of the international press corps witnessing and reporting the regime's collapse.

The popular uprisings in the Middle East were particularly unnerving for the Communist Party, which has pointed to the Arab countries to validate the model of one-party rule. Apparently fearing that the Chinese people might be inspired by the scenes from Cairo, censors at one point even blocked Internet searches of the word "Egypt."

How Media Coverage of the Sichuan Earthquake Changed Reporting in China

On her friend covering the Sichuan Earthquake, Christina Larson wrote in The Atlantic: “At first, Yang told me, the government had issued notice to all newspapers not to send reporters to the quake site; this was similar to the policy after the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, when domestic reporting on the quake's aftermath was all but nonexistent. Yet in 2008, "in mass, we went anyway." Many newspapers used the fact of Premier Wen Jiabao's visit to the region as an excuse to send staffers, claiming that they were covering him, not directly the quake's impact. "Once all those reporters were there, what could the government do? So that time, they let us be." [Source: Christina Larson, The Atlantic March 22, 2011]

“Yang was among those who rushed to the quake site. On the morning of May 12, he and his wife had just been married in a simple civil ceremony in Beijing (the lavish banquet was planned for later). That afternoon, he got an anxious call from his editor. Soon, he was on an early evening flight bound for Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. (That kind of drop-everything missionary zeal might sound familiar to ambitious reporters of any national stripe.) Over the next two weeks, Yang visited hospitals, makeshift shelters, and abandoned buildings. While he remained unscathed, some of his colleagues, traveling in areas where aftershocks sent boulders cascading down hillsides, returned home with neck braces and bandaged limbs.”

“Initially, the government told papers not to publish reports about poorly enforced construction standards “ the result of local corruption “ that had left school buildings especially vulnerable, resulting in the avoidable deaths of schoolchildren trapped beneath rubble. But the information spread anyway, at first through web sites. Once some facts came out, the government allowed a few reports to be published. But when citizen-led campaigns to seek redress began to gather steam, the censors clamped down again, on both the news coverage and the activists themselves.”

“Meanwhile, a colleague of Yang's had discovered that the central government had delayed in accepting aid from the Japanese government because of concerns that foreign aid workers would pass by secret weapons facilities hidden in the hills of Sichuan. Writing about that, which falls squarely in the forbidden category of "state secrets," was obviously off-limits.” When he returned home two weeks later, Yang told his wife he had been able to report more than he had expected, but much less than he would have liked. It was, to him, a sort of partial progress. He later had nightmares about collapsing schools.” "I think sometimes I want to change nationality to be a better journalist," he said.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Lack of Press Freedoms in China

According to the Freedom House’s 2019 Freedom in the World report, China has become “home to one of the world’s most restrictive media environments and its most sophisticated system of censorship, particularly online.” The Freedom House report observes that the government’s ability to monitor online and offline communications “has increased dramatically in recent years.” Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked China fourth to last out of 180 countries on its 2021 World Press Freedom Index In 2009, it ranked China 167th out of 173 countries in its assessment of press freedoms, just ahead of Iran but behind Vietnam.

Although the Chinese Constitution declares that citizens enjoy freedom of speech and freedom of the press, these freedoms are tightly restricted by specific laws and regulations and undermined by a plethora of laws on libel and revealing state secrets. There are no freedom of information laws or freedom of the press in China. If a newspaper prints something the party doesn't like, the government can fire the editors and journalists and shut the newspaper down. The lack of freedom extends beyond the media. Respected professors have been banned from teaching and famous literary critics have been banned from publishing for expressing unpopular views.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are tightly restricted by specific laws and regulations. Typically, the laws and regulations governing cyberspace, the press, and the media contain a list of prohibited content, which includes but is not limited to matters concerning national security, terrorism, ethnic hatred, violence, and obscenity and penalties for violations. [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, June 2019 |*|]

According to article 25 of the Regulation, no publication may contain content on any of the following matters:; 1) Those opposing the basic principles established in the Constitution; 2) Those endangering the unification, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the State; 3) Those which divulge secrets of the State, endanger national security or damage the honor or benefits of the State; 4) Those which incite the national hatred or discrimination, undermine the solidarity of the nations, or infringe upon national customs and habits; 5) Those which propagate evil cults or superstition; 6) Those which disturb the public order or destroy the public stability; 7) Those which propagate obscenity, gambling, violence or instigate crimes; 8) Those which insult or slander others, or infringe upon the lawful rights or interests of others; 9) Those which endanger public ethics or the fine national cultural traditions; 10) Other contents prohibited by laws, administrative regulations or provisions of the State. Persons publishing or importing publications containing such content may be criminally prosecuted or subject to administrative penalties, according to article 62 of the Regulation. |*|

The Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 tested press freedoms. test. After martial law was declared there was some coverage of the protests but when Du Xoan, a popular television anchor, cried during a broadcast the coverage stopped and she was never seen on the air again. Even foreign journalists are not immune from crackdowns. Todd Carrel, a former bureau chief in Beijing for ABC news, wrote in National Geographic, "In June 1992...I reported for ABC on a man who, all alone, showed up unfurl a protest banner...My price for documenting his actions was severe and unexpected. I was kicked and punched by a group of plainclothes policemen, one of whom flailed my head with a bag of rocks. The beating left me hobbled with lasting injuries. I still have difficulty walking, sitting and standing."

Declining Press Freedoms in China

Media freedom in China is declining at "breakneck speed" and journalists there face physical assaults, hacking, online trolling and visa denials, according to a 2022 report by report by the Foreign Correspondents Club (FCC), a group representing foreign journalists in China. Local journalists in mainland China and Hong Kong are also being targeted. China has labelled the FCC an "illegal organisation". [Source: BBC, January 31, 2022]

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and his take on expression China

The report came at a time when China was under scrutiny due to alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang and a crackdown in Hong Kong. The BBC reported: “The report found that foreign journalists are being harassed so severely by the state that a handful of correspondents have left mainland China. Others have been forced to come up with emergency exit plans as a precaution.

“Chinese colleagues of foreign reporters have also faced intimidation with authorities harassing their families, the report said. Sources have also been harassed and intimidated, with many cancelling at the last minute due to pressure from authorities. "One of my sources was detained and sentenced to prison after forwarding me a screenshot. It was a deeply traumatising ordeal, and I have no idea when he will get out," the report quoted one journalist as saying.

“Authorities have also used the pandemic as a way to delay reporting trips and approvals for new journalist visas, the FCC said. This has left bureaus with staffing issues, impacting how they have been able to report on the country. For reporters attempting to cover Xinjiang — the controversial region that is home to many of China's Uyghurs — 88 percent of respondents said they had been followed. China's government has been accused of committing genocide against the Uyghurs, something it denies. “One reporter said they were accosted by men in plainclothes who physically assaulted them. "The videographer and I both got hit in the face, my lip was bleeding and they confiscated some of our equipment," they added.

Watchdog Journalist Wang Keqin

Wang Keqin, a pioneering investigative journalist, has received death threats from criminals and the wrath of officials. He some unusual methods. For example, he carries a small, red-smudged, battered metal tin and compiles witness statements and then secures fingerprints at the bottom to confirm agreement. In May 2010, Wang’s boss was removed as the editor of China Economic Times following Wang's report linking mishandled vaccines to the deaths and serious illnesses of children in Shaanxi province. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, May 23, 2010]

Wang began his career as an official in western Gansu province writing propaganda stories “like accountants working under the leadership of the Communist party with a red heart” and how he cobbled together articles for local media for a bit of extra cash. But as residents sought him out with their problems, he found his conscience stirring. “They enthusiastically welcomed me into their homes, told me their stories and looked at me with high expectations. As a 20-year-old it was the first time I was paid so much attention and I felt a great responsibility. I had to tell their story.”

By 2001 he was “China's most expensive reporter” — a reference to the price put on his head for exposing illegal dealings in local financial markets. Soon afterwards another report enraged local officials and cost him his job. “I had problems with black society [gangs], and problems with red society [officials],” Wang said. “I heard there was a special investigation team, [with the target of] sending me to prison.” He was saved when Zhu Rongji, China's premier in to protect him.

Blackmailing Reporters in China

Chinese reporters today routinely accept payments to run favorable stories on people, businesses or organizations that pay them. Payments range from red envelopes with “transportation money” for reporters that show up at news conferences to 300,000 yuan bribes to newspapers that run positive stories on the conduct of the local government [Source: Washington Post]

Some reporters even seek out black mail money in return for not printing unfavorable stories. The practice is said to be routine. There are many stories of reporters deliberately going after dirt so they can use it to blackmail businesses and government agencies and anyone else who has money.

The thinking behind the practice goes: if the government can distort the news for political reason then why can’t reporters do it the same for money. The Washington Post wrote a story about a reporter that accepted a $2,000 “shut-up fee” not publish a story about wrongdoing at a health clinic in the southern city of Shenzhen that allegedly performed operations, including abortions, it was not authorized to perform.

When word gets out about a mine disaster hordes of reporters and even people posing as reporters show up demanding money yo keep quiet. An official at a mine that suffered a devastating flood told the Washington Post he gave out $25,000 in shut-up money and still more people showed demanding more. Occasionally reporters get reprimanded or fired and newspapers get closed down and people get charged for impersonating reporters but it doesn’t happen very often.

Muckraking reporters can be hired for a fee to investigate corruption or some other problem and write their findings on the Internet. Farmers in one town paid a reporter a negotiated fee of $65 to uncover corruption among local officials who wanted to take their land and was posted on the website China’s Famous Reporter.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Plight of Chinese Journalists

On her friend say his life as journalist, Christina Larson wrote in The Atlantic: “His appraisal of his career so far as a journalist in China — brimming at once with earnestness and cynicism (a contradiction not uncommon, somehow, in many fields in China) — has stayed with me. Over cheap bijou, he shared his exploits covering illegal border crossings in Burma and sneaking into North Korea (he had posed as a tourist, and brought his wife along for cover).” [Source: Christina Larson, The Atlantic March 22, 2011]

“Alas, the resourcefulness and capacity for personal heroism among some, not all, Chinese reporters too rarely shows through in the final published product. The censor's red pen is hardly the only obstacle. Equally powerful is the appointment system for top personnel. The government designates the editor-in-chief of every newspaper — sometimes it's someone with no interest in the position per se, simply a bureaucrat on his way from being vice-mayor of one city to another. Among other things, this means there's little hope for young stars to rise and envision themselves as leaders. Eventually, the best and brightest, the would-be reformers, drop away.”

In recent months, Yang's aspirations have shifted. Having butted up against the low pay and fact that he'll never advance to the top based on the caliber of his work, he is looking for another career. "The track has ended," he told me. "There is nowhere forward to go." His eyes, as ever, looked big and round, but now somehow dimmer.

I suspect Yang's dilemma — and his career trajectory of hope and disillusionment — could be a metaphor in the future not only for the contradictions of journalism in China, but more generally for the challenge of keeping talent on track in creative fields. Over the next decade, China's government is endeavoring, simultaneously, to transition its economy by fostering a more innovative and entrepreneurial society (per the recently adopted 12th Five Year Plan starkly on information freedom and the Internet. So, how do you hold onto people paid to come up with new ideas — scientists, writers, academics, entrepreneurs — when they bump up against the limits of what's permissible to say? Meanwhile, as for Yang, one alternate career plan is to make money on real-estate speculation.

Long Can, a reporter fired for writing a fake news story that was probably true, told Deutsche Welle; “I’ve been a journalist for 10 years. I’ve never accepted a red envelope [in payment for or against news coverage]. What we make can’t be considered an enviable wage. We keep to our original journalism ideals through the years, and those “ideals” are what we lean on as we plod ahead. Being a journalist has always been cruel and difficult. We always hope for even the simplest measure of care, even the merest regard for our ideals, but these have never in fact been granted — not in terms newspapers themselves or the larger media environment. As journalists we bear all of the risks and pressure. But then we find at the critical moment that we’re 'cast as failures; ...Before I worked hard to ensure that I kept my cool. But this time I’m furious. I feel I’ve lost hope for “journalism.'"

Arrests, Imprisonment and Human Rights Violations Against Journalists in China

China has more imprisoned journalists than any other country. According to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, China remained the world’s worst jailer of journalists for the third year in a row in 2021, with 50 behind bars. As of September 2007, China held 35 journalists and 51 Internet dissidents in prison. By comparison 31 journalists were in prison in 2006 and 42 were in jail in 2004. About three quarters of the journalists were in jail on vague charges for subversion or revealing state secrets.

One journalist was placed on a most-wanted list after a negative story he wrote about a battery manufacturer was published. Another was sentenced to 15 years in prison for “threatening nation security.” In August 2010 four reporters were detained by police for probing the plane crash in Yichun, Heilongjiang Province that killed 42 people. Police later said the detention was a misunderstanding.

In 1992 Xinhua News Agency editor Wu Shishen was sentenced to life in prison for leaking a key speech head of its delivery to a Hong Kong reporter in 1992. He was imprisoned from 1993 to 2005. In January 2006, Chinese journalist Li Changqing was sentenced to jail for three years for “spreading false and alarmist information.” It was is widely believed to that he was punished for helping an imprisoned anti-corruption crusader.

Gao Qinrong, an investigative journalist for the official Xinhua press agency, was sentenced to 13 years in prison on charges connected with reporting on a bogus irrigation project. He was released after eight years in prison in 2006 and acclaimed as a corruption fighter. Pang Jianming, a reporter for the China Economic Times, was fired, prevented from working for other publications and forced to undergo “Marxist ideological education.” His crime: writing a series of stories about substandard materials put in concrete used to make tunnels for a $12 billion high-speed railroad.

In August 2010, plain clothes police officers arrested 55-year-old a Beijing writer Xie Chaoping, who previously accused the local government in Weinan, Shaanxi Province of embezzling funds meant for residents who were forced to relocate because of the Sanmenxia reservoir project. He was charged with “illegal trading.” Xie's daughter told the Global Times Wednesday that Xie was held at a local police station for nearly two weeks, and the local police provided no explanation about her father. “My father's mobile phone was also confiscated by the police and we cannot contact him,” she said. [Source: An Baijie Global Times, September 2, 2010]

Violence Against Journalists in China

Giles Lordet of Reporters Without Borders said, “For journalists who embarrass local government officials or other very powerful people, China is a very dangerous place.”Journalists have been beaten, detained and sued. In a village in Shandong Province an official was caught on video tape slapping a female television reporter. The video got a lot of exposure after it was posted on the Internet. In China you can find blackmailers posing as journalists and thugs hired by targets of unflattering news stories who beat up the reporters who wrote the stories.

One night Fang Xuanchang, an investigative reporter with Caijing magazine, was jumped by two men with lead pipes men outside his home. The men beat Fang’s head and upper body, unconcerned about people passing by. “They tried to kill me,” said Fang, who, covered in blood, managed to make it to a taxi and get help. He thinks his attacker were hired by doctors that he exposed for promoting miracle cures using research by quack scientists.[Source: John Gliona, Los Angeles Times, August, 2010]

In January 2007, a Chinese journalist was beaten to death with iron bars and pick axes by 20 thugs outside a coal mine near the city of Datong in Shanxi Province. The journalist sustained a broken arm, was bruised all over his body and appeared do have died of a brain hemorrhage. The incident attracted a lot attention. Chinese President Hu Jintao ordered a thorough investigation. The Committee to Protect Journalist reported that a newspaper editor was beaten to death by police officers angry over reports about their involvement in corruption.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Testimony of Attacked Chinese Journalist

Fang Xuanchang, an editor at Caijing magazine, was on his way home from work around 10:30 on the night of June 24 when he was attacked by two men wielding metal clubs. Fang is a respected science-and-technology journalist, who joined Caijing in March. He believes the attack was connected to his reporting, though he is hoping that police will investigate this vigorously enough to confirm that. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker July 6, 2010] Xuanchang told The New Yorker blog: “I originally thought I was hit by a soccer ball or something, so I didn’t even bother to look back and I just kept walking, until I was beaten again on the back-left side of my head. In retrospect, the first round of the attack was aiming at the back of my head, which is a crucial area, with two metal pipes. It was only because I walked fast, and the attackers moved a bit slow from behind, that they hit my back instead of my head.”

“As I stopped and turned around, my back and shoulders were hit continuously, and then I saw two metal pipes crashing down on my head. Luckily, I was rather calm, and I leaned back just in time to avoid that hit. After that, a series of attacks came down on my head. It was impossible for me to fight back, until I struggled backward for ten or twenty meters, and then ran off for about ten steps, out of their reach, and I was able to face them again. The attackers seemed experienced, in that they didn’t approach me from the front. I tried to kick them, but they withdrew and dodged my kicks; meanwhile, hit my left ankle with the metal pipe, and then ran off to the South.”

“Because my head wound was pouring blood, my shirt and pants were soaked in blood. There was blood all over the ground as well. I knew I needed to get to the hospital. But when I walked back south to the intersection and tried to hail a taxi, the two attackers rushed out from the dark again. They kept beating my head and preventing me from getting a taxi. I had more time to prepare this time, and, fortunately, was calm enough to dodge their blows. I lowered my upper body and ran to the construction site nearby, where subway line No. 9 is under construction. It was only when the attackers realized I was trying to find tools to fight back that they ran off. But they were still watching me from about thirty meters away and waiting for the chance to attack again.”

“At that moment, a taxi stopped in the middle of the intersection and let get in. I was finally able to get to the hospital...The entire incident lasted about four minutes. The next day, by examining the bloodstains on the street, I remembered that there were five or six rounds of attacks, leaving huge blood stains around those areas. There was blood tracked over fifty meters. When I was being attacked, there were many people watching, but the attackers didn’t have to care because, perhaps according to their experience, no one would stand up and help. No one would even dare to call the police. Based on all of this evidence, the two attackers were probably experienced professionals. Their intention was to kill me on the spot, or leave me bleed to death by preventing me from getting to the hospital.”

“I was fortunate that the Naval General Hospital was only a few hundred meters away. The taxi driver noticed that it was emergency and ran red lights to get straight to the hospital. About five minutes after I reached it, I was half-conscious from losing so much blood. The results of my medical examination say: six-centimeter by six-centimeter hematoma on the rear of the head; a five-centimeter deep cut that reached the skull; no estimate on the amount of blood lost; a C.T. exam showed no brain injury. After cleaning up the blood on the rest of my body, I found seven injuries, mostly on my back, from the first round of surprise attacks.”

The police took down the first notes on the 25th before daybreak, and it was soon put on file for investigation and prosecution. The criminal police were involved on the 26th. As of now, it is almost certain that the incident was retaliation for investigative pieces that I have written, because I have never messed with anyone in my personal life. Meanwhile, after further investigation, we have almost confirmed that the two attackers would have not mistaken me as someone else.

This is has been a shock to Chinese journalists. At first, I worried about whether or not should I inform my fellow journalists, because it might have a negative impact on their future reporting. Some of the journalists might not want to be a whistleblower, to expose the truth, if their personal safety is at stake. However, if this type of thing goes unnoticed and un-discussed, China will have even less chance to build a system that can protect its journalists from future tragedy.

Blogger Xu Lai Stabbed in Bookshop

In February 2009, the blogger Xu Lai (also spelled) was stabbed in a Beijing bookshop after giving a speech there. Eyewitnesses said his attackers accused him of “offending people.” Xu wrote under the name pen name ProState. His blog, “ProState in Flames” was read by 130,000 visitors a day and was famous for reprinting a variety of interesting material which often does not get into the mainstream media , Hosted by the liberal blog-host Bullog, the blog was shut down and forced to move locations several times.

According to the Southern Metropolis Daily newspaper, two men grabbed Xu shortly after he finished speaking and dragged him into the toilets. When his wife forced her way in, she saw that one was holding a dagger while the other one had a kitchen knife and was preparing to hack Xu's hand. The men fled from the One Way Street bookshop before anyone could catch them.

It was not determined who the attackers were. According to various reports, the attackers said either "We're here for revenge," "You'll know better than to offend people next time," or "You brought this on yourself. You know why you're doing this, don't you?" According to the Southern Metropolis Daily he described Xu as "a low-key sort of person who wouldn't provoke anyone. However, there are many things on his blog that can touch a nerve and he has probably made enemies that way."

Reporter Killed Because of the Cooking Oil Scam?

AFP reported: “A Chinese journalist who had been following a scandal involving the sale of cooking oil made from leftovers taken from gutters has been stabbed to death, police and state media said. Li Xiang, 30, a reporter with Luoyang Television Station in the central province of Henan, was knifed more than 10 times as he returned home from a karaoke session with friends, the Zhengzhou Evening News reported. [Source: AFP, September 20 2011]

The laptop computer Li had been carrying was missing and police were treating the case as a murder-robbery, but have not ruled other motives, the report added. The last post on Li's micro-blog on September 15 said web users "had complained that Luanchuan county (in Henan) has dens manufacturing gutter cooking oil, but the food safety commission replied that they didn't find any".

Bloggers said they suspected Li's death was related to his previous reports on the "gutter" cooking oil cases."Luoyang Television Station reporter Li Xiang got stabbed to death, I suspect it's related to his reports on 'gutter' cooking oil," a web user said on Sina's popular social networking site Weibo. "Li Xiang's stabbing death is the unfortunate outcome of investigating the gutter cooking oil cases," another user said.

In September 2011, police in central Henan Province arrested two men suspected of killing Li. Police in the city of Luoyang said the murder was not connected with the gutter oil scandal. They said the two suspects killed Mr. Li during a robbery early morning outside the gate of his apartment complex. The men stole his laptop, camera and wallet after stabbing him 10 times, the police said. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, September 21, 2011]

Image Sources: Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022