HIMALAYAN MARMOTS

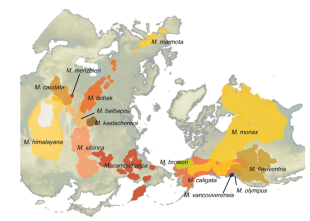

The Himalayan marmots (Marmota himalayana) is a marmot species that inhabits alpine grasslands throughout the Himalayas and on the Tibetan Plateau. Marmots are rodents and essentially are large ground squirrels. Himalayan marmots are one of 15 Marmota species alive today. Marmota can be found in Asia, Europe, and North America, where they are known as groundhogs or woodchucks. Himalayan marmots are found at high elevation in northwestern south Asia and China, particularly on the Tibetan plateau in China and the Himalayan and Karakorum mountains ranges of India, Nepal, China, Pakistan and Bhutam.[Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Himalayan marmots in tundras, desert, dune areas, savannas, grasslands, and mountains and agricultural areas at elevations of 2500 to 5200 meters (8200 to 17060 feet). They are found most often between timberline and snowline, at elevations above 3,500 meters (11,482 feet), where temperatures are usually below 10̊C. They occur primarily in dry, open habitats, including alpine meadows, grasslands, and deserts. In the northwestern Himalayan region. Here, vegetation is dominated by stunted evergreen shrubs and birch-dominated forest patches in the lower alpine regions and transitions to open alpine meadows at higher elevations. Many of these are protected due to the presence of endangered snow leopards.

Himalayan marmots have a lifespan between 12 and 17 years in the wild, with an average of 15 years. Like other marmots, Himalayan marmots dig large burrows, which generally means their range is restricted to areas with light-textured and adequately deep soil. The burrows of Himalayan marmots are unusually deep, typically ranging from 2.0 to 3.5 meters in depth. In preparation for winter hibernation, they sometimes dig burrows that reach depths of 10 meters. Such burrows are shared by all members of a colony during the hibernation period. /=\

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Himalayan marmots are listed as a species of Least Concern because they range over a large area and appear to have a large population. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Himalayan marmots are locally abundant throughout their range, which is often in places where humans are scarce, and show no signs of decline. Many live in areas protected for snow leopards, which are classified as endangered by the IUCN. Historically, Himalayan marmots have been eaten as food, trapped for fur and their flesh has reportedly been used in traditional Tibetan medicine, for treatment of renal disease. /=\

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MARMOTS IN CENTRAL ASIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, RANGE factsanddetails.com

MONGOLIAN MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, THE PLAGUE AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BLACK-CAPPED MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Himalayan Marmot Characteristics

Himalayan marmots range in weight from four to 9.2 kilograms (8.81 to 20.26 pounds) and range in length from 47.5 to 67 centimeters (18.7 to 26.4 inches), excluding their tail which is 12.5 to 15 centimeters (4.9 to 5.9 inches) in length. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Marmots — sometimes referred to as large ground squirrels — are large terrestrial rodents with stout limbs and short tails. Himalayan marmots are similar in size housecats and are larger than other marmot species. They are particularly stout-bodied and have relatively large skulls, ranging from 9.6 to centimeters in length, and exceptionally large hind feet, which range in length from 7.6 to 10 centimeter and are well-suited for digging. Like other marmots, each forefoot has four-toes with long concave claws for burrowing, and each hind foot has five toes. Their tails are shorter than many other marmot species. Their ears, ranging from 2.3 to 3 centimeters in length, are also relatively short compared to other marmot species.

The back fur of Himalayas marmots ranges in color from yellow to brown. These rodents often have irregular black or blackish brown spots, particularly on the face and snout. Fur on their chest is buff yellow to russet. Two subspecies of Himalayan marmots have been described: 1) m. himalayana himalayana and 2) m. himalayana robusta. Marmota himalayana robusta is especially large, with individuals reportedly weighing over six kilograms./=\

Himalayan Marmot Eating Behavior and Predators

Himalayan marmots are primarily herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts) and are also recognized as folivores (eat leaves), frugivores (eat fruits), and granivores (eats seeds and grain). Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, roots, tubers, seeds, grains, nuts and fruit. [Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Old plant growth is commonly avoided due to the presence of alkaloids, which emit a bitter, metallic taste. Most marmots prefer flowering flora because they are more palatable, and select plants containing higher amounts of protein, fatty acids and minerals. Plant selection differs throughout the year as certain flora species are only available seasonally. Himalayan marmots are sometimes sympatric with livestock such as domesticated yaks and feed in the same pastures.

Predators of Himalayan marmots include snow leopards, Tibetan wolves, and large birds of prey like bearded vultures and golden eagles. Himalayan marmots are important foof sources for snow leopards, making up nearly 20 percent of the snow leopard diet in some places..Brown bears may also prey on Himalayan marmots.

Marmots keep on eye for predators when they are out of their burrows. Distances that marmots venture from their burrows are correlated with colony size and time spent scanning for predators. Members of smaller spend more time scanning for predators and don’t venture as far from their burrows as members of large colonies. When Himalayan marmots sense a predator approaching, they use a distinct series of calls to warn other members of their group. These alarm calls consist of rapidly repeating sounds, beginning with a low frequency call. Each call typically lasts less than 80 milliseconds. A single series of calls continues for less than one second. Alarm calls are repeated usually every five to 20 seconds. Alarm calls in Himalayan marmots can be distinguished from those produced by other marmots, as the first and second sounds in each series occur in much more rapid succession. /=\

Himalayan Marmot Behavior

Himalayan marmots are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing),diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), hibernate (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups) and colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other). [Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Activity of Himalayan marmots peaks during morning and late afternoon. Most marmots live in colonies with up to 30 individuals. The size of Himalayan marmot colonies depends on the availability food and other resources. One social interaction frequently observed among marmots is their greeting — a behavior common to many rodents — that occurs after a period of separation when individuals emerge from their burrows in the morning or afternoon. The greeting consists of a nose-to-nose, nose-to-mouth or nose-to-cheek exchange. Marmots also engage in "play fights", which sometimes look violent and aggressive but usually typically are not. The length of play fights varies with age and sex. Those of female marmots and yearlings typically last longer duration than those of adult males and infants.

The behavior of Himalayan marmots varies with the seasons. They hibernate for a long period — typically for six to eight months during the coldest times of the year. They are active in spring, summer, and early autumn. Adult females and yearlings spend more time inside their burrows during late spring and early summer. Adult males spend more time outside their burrows. They appear alert and presumably are th ones with the primary duty of scanning for potential predators. They do this until August. By mid- to late-August, both sexes spend more time in their burrows. /=\

See Separate Article: HIBERNATION: PROCESSES, DIFFERENT TYPES, ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Himalayan Marmot Senses and Communication

Himalayan marmots sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). [Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Marmots have strong tactile senses, well-developed for burrowing. Quick reflexes also allow marmots to respond rapidly to their wide range of environmental influences and social interactions. Marmots are highly alert and rely heavily on visual and auditory senses to alert them to potential predators. Per-capita time spent scanning decreases as colony size increases.” Marmots that forage in groups tend to spend less time watching for predators while those that forage alone continually pause, scanning the surrounding environment for predators. Marmots that feed individually often spend nearly twice the amount of time watching for predators. Distance from their home burrow also affects alertness. Marmots that stay close to their burrows, tend to be less vigilant in scanning their surroundings than those foraging at greater distances. /=\

Himalayan marmots communicate by whistling or chirping, and using physical behaviors. When a predator is detected, many marmot species produce a series of alarm calls. It is unclear if there is a distinct vocalization associated with mating. In some species, such as woodchucks, males attract reproductive females using pheromones.

Himalayan Marmot Mating and Reproduction

Himalayan marmots are monogamous (having one mate at a time), polyandrous (with females mating with several males during one breeding season) and cooperative breeders (helpers provide assistance in raising young that are not their own). They engage in seasonal breeding — mating once yearly, typically during February and March. The number of offspring ranges from two to 11, with the average number being six .The average gestation period is one months. On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two years.[Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Many marmot species live in family groups consisting of a reproductive territorial pair, subordinate adults, yearlings and young. Most marmots are monogamous but in some species, females have multiple mates. Because of their burrowing tendencies, Himalayan marmots are difficult to observe in their natural habitat and few detailed studies of their mating behavior have been undertaken. However, certain physical interactions, such as nestling and nibbling, appear indicate an individual is ready and willing mate.

All species of marmots reach reproductive maturity by the age of two. However, reproduction typically is delayed another year or more. According to Animal Diversity Web: When marmots reproduce early in the year, it is more physically stressful. Because female marmots do not gain body mass during lactation (and may lose body mass), early reproduction presents risks, as they have to rely on favorable food availability and weather conditions in the future to sustain their reproductive effort. Reproductive females gain mass at least three weeks later than females that don’t have young, but generally within a relatively short period of time the reach weights similar to those of barren females. The inability of pregnant females to gain weight may lead to the failure of weaning their young.

Himalayan Marmot Offspring and Parenting

Himalayan marmot young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. Parental care is provided by females. The average weaning age is 15 days. During the pre-weaning and pre-independence stage of development provisioning and protecting are done by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. [Source: Lacey Padgett and Christine Small, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

As is true with most marmots, Himalayan marmots give birth in late spring and early summer. This coincides with the end or near end of hibernation. Himalayan marmots typically produce two to 11 offspring in each litter. Variation in litter size often reflects overall population density. When population density is high, females yield an average of 4.8 offspring per litter. In less dense populations, females average seven pups per litter. After offspring become independent, they maintain permanent residences in their familial communities — typical behavior among most marmot species. /=\

Most marmots provide considerable care to their offspring. Special care is provided during hibernation, when adults aid the social thermoregulation of the young. This may be a form of alloparental care, whereby unrelated adults aid in care of the offspring. Among Olympic marmots, offspring remain in the burrow for at least one month after birth. Most marmots receive nearly constant care from the mother, both while in the burrow and for several weeks after emerging. After several weeks, offspring of most species are capable of foraging independently. There are are similarities and differences in cooperative breeding and alloparental care of different marmot species.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025