MONGOLIAN MARMOTS

Mongolian marmots (Marmota sibirica) are also known Tarbagan marmots, Siberian marmots, Tarvaga in Mongolian and Tarbagan in Russian. They are a kind of large ground squirrel and species of rodent in the Sciuridae (squirrel) family. [Source: Wikipedia]

Mongolian marmots are active about six months a year and hibernate an equal amount of time. They have a single alarm call, but there is also individual variability. Little is know about the lifespan of Mongolian marmots. Lifespan of marmot species ranges ranges from 13 to 15 years in the wild and from seven to 21 years in captivity.

Mongolians prize the meat and oil of Mongolian marmots and export their fur to Russia. Hunting them is a major pastime. According to Dr. J. Batbold, a Mongolian marmot expert, hunters shoot them from horseback and camouflage themselves with large "bunny-like" ears and also "dance" and wave a white yak-tail to get the marmots to stand up and be more easily shot. Marmots in some parts of Mongolia carry the bubonic plague (Yersina pestis) and have passed it on to humans via infected meat. Dr. Batbold's research has shown that plague-resistant populations have a higher body temperature. Tarvaga have a single alarm call, reminisent of their close relatives bobak and gray marmots.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MARMOTS IN CENTRAL ASIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, RANGE factsanddetails.com

HIMALAYAN MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BLACK-CAPPED MARMOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Mongolian Marmot Habitat, Range and Subspecies

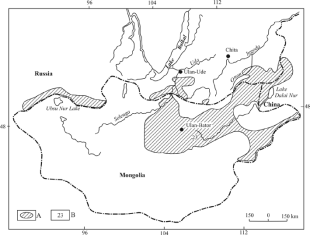

Mongolian marmots live mainly in northern and western Mongolia at elevations of 600 to 3,800 meters (1,970 to 12,470 feet). They are are found in Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang in the Manchurian region of China and in southwest Siberia, Tuva and Transbaikalia in Russia. In the Mongolian Altai Mountains, their range overlaps with that of Gray marmots.

Mongolian marmots live grasslands, shrublands, mountain steppes, alpine meadows, open steppes, forest steppes, mountain slopes, semi-deserts, river basins, and valleys — places with enough vegetation for grazing and foraging. ongolian marmots occasionally forage at elevations higher than 3000 meters (9,842 feet) when vegetation is scarce. [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

There are two subspecies:Marmota sibirica sibirica and Marmota sibirica caliginosous. Within Mongolia, M. s. sibirica lives on the eastern steppes and the Hentii mountain range while M. s. caliginosous occupies the northern, western, and central regions of Mongolia, as well as the Hangai, Hövsgöl, and Mongol Altai mountain ranges. The two subspecies typically reside at different elevations, with M. s. sibirica occupies living lower steppes and grasslands whileM. s. caliginous occupies higher mountain ranges and slopes.

Mongolian Marmot Characteristics

Mongolian marmots are rodents with stout bodies and short limbs. They range in weight from six to eight kilograms (13.2 to 17.6 pounds) and have a head and body length that ranges from 50 to 60 centimeters (19.7 to 23.6 inches). Their tails are bushy and approximately one half of their body length. /=\ Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females and have significantly larger mandibles (jawbones) than females. . [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The fur of Mongolian marmots is primarily brown in color, medium length, and fine in texture. On their back side, their fur is light brown to light rusty colored, often with hints of light, whitish yellow. The color of the fur undergoes minor seasonal changes — from light grayish brown in the spring to reddish brown in late autumn. The fur on the rostrum (frontal structures projecting out from the head) and around the eyes as well as the tail is darker brown. The ears are light orange-brown.

Harry VanDusen wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Mongolian marmots has robust post-orbital processes. The lateral side of the anterior zygomatic arch is lozenge-shaped. The crown of the second upper premolar and the crown of the first molar are equal in size, but are both smaller than the crowns of the last two molars. One of the most important skeletal features of this species is the mandible, both in size and shape. This feature helps to place the species within morphologically-based phylogenetic trees. Mongolian marmots and gray marmots have extremely similar mandibles, and this similarity has been put forth as evidence for a close phylogenetic relationship between the two taxa. The two species also have similar external characteristics and are know to have hybridized. point. However, gray marmots are larger than Mongolian marmots, and they lack the pronounced sexual dimorphism is present: in the mandibles of Mongolian marmots.

Mongolian Marmot Food, Predator and Ecosystem Roles

Mongolian marmots are herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts), and are also classified as folivores (eat leaves). Their diet is fairly basic and consists primarily of grasses. On top of this they eat 10 to 15 types of herbs as well as wood plants like sagebrush. Cellulose content of a typical diet is 20 to 25 percent. When this cellulose content is too high, food consumption and assimilation decreases. [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In order to forage for fresh vegetation, Mongolian marmots often climb higher in elevation to reach unspoiled food supplies. After hibernation and for the first half of their active season, they primarily eat grasses and some herbs. During the second half of their active season, however, they eat mostly herbs. Because of this, habitats completely dominated by grasses are avoided. preferred.

The most common predators of Mongolian marmots are red foxes, wolves, hawks, buzzards, brown bears, snow leopards, and eagles. Their anti-predator adaptions include brownish colored fur that blends in with the soil of their habitats. They emit alarm calls to warn others of the presence of predators. They also stay close to their burrows in case they have to make a quick escape. Juveniles experience the highest rates of mortality, especially in the spring when they often play around the burrows and are exposed to predators. Older marmots are catious and more vigilant and dart back into their burrows at the slightest hint of danger.

Mongolian marmots are keystone species, playing a pivotal role in the ecosystem they occupy. Their burrows help aerate soil, water drainage are used by animals such as corsac foxes, who are not as adept at digging as marmots. It is believed that if populations of Mongolian marmots decline, that populations of corsac foxes also decline. When burrowing, Mongolian marmots create mounds with unique vegetative characteristics that vary with level of disturbance. These mounds are usually dominated by one species of plant. In a Stipa steppe in Mongolia (a common habitat of Mongolian marmots), vegetation mounds were commonly comprised of Stipa krylovii, Artemisia adamsii, and Leymus chinensis. When there were disturbances to marmot populations declined species richness decreased in vegetation mounds, especially in those dominated by Leymus and Artemisiam, but the forage quality in Leymus and Artemisia mounds improved. /=\

Mongolian Marmot Behavior

Mongolian marmots are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), hibernate (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements), territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The size of Mongolian marmot range territory is generally around two to six hectares (2.5 to 15 acres). Some studies concluded that Mongolian marmots prefer to maintain a home range of three to six hectares, but can live unfavorably on two hectares . Other studies indicate that they live okay 1.7 hectares. This variation is explained to available vegetation. When resources are scarce, Mongolian marmots are more likely to expand their range to search for food.

Mongolian marmots are fairly strong and most active in before noon. They communicate with sound and sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. One of the most important forms of communication for marmots is their alarm call. The acoustic makeup of their alarm call is unique to this species and has been used to distinguish them from other kinds of marmots, particularly gray marmots. Mongolian marmots become more perceptive to predator approaches with age, allowing them to quickly retreat into their burrows.

Mongolian marmots begin hibernation in the fall in their burrows. They use dirt, sticks, feces, leaves, and urine to seal their burrows during hibernation. The length of hibernation is influenced by weather and summer food conditions. /=\

See Separate Article: HIBERNATION: PROCESSES, DIFFERENT TYPES, ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Mongolian Marmot Social Behavior

According to Animal Diversity Web: Mongolian marmots are social animals, living in large colonies of their extended family. This extended family is comprised of a dominant adult pair, subordinate adults, and all of their yearlings (offspring that have yet to be dispersed). Family behavior is largely determined by external factors. In favorable conditions, Mongolian marmots live in long-lasting, stable families of 13 to 18 individuals. Unfavorable conditions produce unstable, short-lived families of two to six marmots. Mongolian marmots are socially integrated in the summer, only separating for a short time. Population density can be influenced by the timing of vegetation growth; the earlier the vegetation begins to grow, the denser the marmot population. /=\

Mongolian marmots are very territorial. In an area of sympatry of Mongolian marmots and Gray marmots, Mongolian marmots forced the other species into bouldery screes. Through this territorial behavior, they were able to freely inhabit the most advantageous habitats. While remaining territorial, Mongolian marmots were found to coexist in the same territories as Gray marmots. This supports the theory that these two species occasionally live in mixed families, implying an increased chance of hybridization. /=\

Because of their relatively large body size and short active season, Mongolian marmots exhibit a behavior called delayed dispersion. The growing season after birth is very short, and juveniles cannot reach a maturity index that would allow them to successfully disperse before their first hibernation. They require an additional summer to reach this maturity index. However, by that time, the individuals have become solidified in a social group. They are dominated by older marmots in the extended family colony, causing them to suppress reproduction and participate in alloparental care of offspring. This care comes primarily in the form of group hibernation (social thermoregulation). When they finally have the opportunity to reproduce, they are well beyond sexual maturity. Mongolian marmots usually disperse at age three. /=\

Mongolian Marmot Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Mongolian marmots are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polyandrous (with females mating with several males during one breeding season). They engage in seasonal breeding — mating in April and breeding approximately every other year. The number of offspring ranges from four to eight. The gestation period ranges from 40 to 42 days. Births occur at the end of May, and young emerge from the burrow in June. Weaning in other marmot takes place after 28 to 46 days. On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two years but they generally don’t start breeding until they are three years old or older. [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Mongolian marmots mate in-group, meaning they reproduce with individuals from the extended family colonies in which they live. The marmots pair off within their colony to reproduce, forming either monogamous or polyandrous relationships. In any given year, the percentage of females who reproduce ranges from 17 to 77 percent, although usually no more than 50 percent reproduce. During years with abundant rainfall, a higher percentage of females reproduce. /=\

Mongolian marmots engage in delayed reproduction, meaning they are capable giving birth much later than when their normal reproduction cycle says they should. This ability is measured by the maturity index, which is a ratio of an animal’s size to the size of a mature adult. At a maturity index of 0.65, Mongolian marmots should be able to reproduce. Instead, females usually reproduce at the age of two or three, at which time their maturity index is greater than 0.65. /=\

Parental care is provided by both females and males. Both sexes do provisioning and protecting are during the pre-independence and post-independence stages of their offsping’s development. Although weaning of marmots usually occurs between a month and a month and a half, juveniles often stay in their parent’s family group for three years. This late date of independence is sometimes called dispersal. Extended family members within a colony sometimes help out with parenting. Family groups engage in group hibernation in the winter. This alloparental care increases overall species survival. /=\

Mongolian Marmots, Humans, the Plague and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Mongolian marmots are listed as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Mongolian marmots in Russia are particularly threatened, as they rarely occur in the wild. This species is protected under the Mongolian Protected Area Laws and Hunting Laws, though these laws do not specifically focus on Mongolian marmots. [Source: Harry VanDusen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Humans utilize Mongolian marmots for food and their body parts are source of valuable materials and medicines. Mongolian herders eat the meat of Mongolian marmot for food and use oil harvested from them because as it contains high levels of corticosterone, traditionally used as a leather conditioner, dietary supplement, and a remedy for burns, frostbite, anemia, and tuberculosis. Furs are used locally and sold for profit in national and international trade. Sport hunting of Mongolian marmots also occurs.

Mongolian marmots are carriers of the bubonic plague (Yersina pestis). They have been known to cause outbreaks in their environments when infected with parasites such as Certrophyllus silantievi (fleas) and ticks of the genus Rhipicephalis. An outbreak of the plague in 1911 caused the deaths of 50,000 people; an outbreak in 1921 caused 9,000 deaths. Both outbreaks were attributed to disease-carrying Mongolian marmots. Studies have indicated that infected marmots need not be spread out over a large area to to cause a wide-scale impact. Humans can get the plague by eating the meat of diseased marmots. Some populations of Mongolian marmots develop a rapid genetic immunity to the plague, indicated by higher body temperature. /=\

Mongolian marmot populations have experienced a long term decline. About 70 percent of the population was lost in the 1990s. This decline is primarily attributed to human hunting food, fur, sport that increased after the Soviet Union fells and to disease (the plague). Between 1906 and 1994, 104.2 million Mongolian marmot skins were prepared in Mongolia alone. Fear of the plague has led to massive extermination campaigns, killing off both infected and healthy marmots. /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025