METHODS OF WORSHIP IN CHINA

Offerings to the gods

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: “Worship generally takes the form of individual prayer or meditation. One form of spiritual practice that is very popular is physical exercise. There are three main traditions. Wushu, a self-defense technique known in the West as gong fu (or kung fu), combines aspects of boxing and weapon fighting. Tai chi chuan (or taijiquan), is a series of slow, graceful gestures combined with deep breathing. The exercises imitate the movements of animals, including the tiger, panther, snake, and crane. Qidong is a breathing technique that is intended to strengthen the body by controlling the qi, or life energy. These exercises are practiced by people of all ages and walks of life; large groups often gather in parks or other public spaces to perform the exercises together. [Source:Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: ““The gods of the Chinese being of this heterogeneous description, it is of importance to inquire what the Chinese do with them. To this question there are two answers, they worship them, and they neglect them. It is not very uncommon to meet with estimates of the amount which the whole Chinese nation expends for incense, paper money, etc., in the course of a year. Such estimates are of course based upon a calculation of the apparent facts in some special district, which is taken as a unit, and then used as a multiplier for all the other districts of the Empire. Nothing can be more precarious than so-called "statistics'' of this sort, which have literally no more validity than that census of a cloud of mosquitoes which was taken by a man who " counted until he was tired, and then estimated." [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 –1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, Chinese Characteristics was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there]

Multitudes of Chinese will testify that the only act of religious worship which they ever perform (aside from ancestral rites) is a prostration and an offering to heaven and earth on the first and fifteenth of each moon, or in some cases on the beginning of each new year. No prayer is uttered, and after a time the offering is removed, and as in other cases, eaten What is it that at such times' the people worship? Sometimes they affirm that the object of worship is " heaven and earth." Sometimes they say that it is "heaven," and again they call ti " the old man of the sky" (Jade Emperor).

In some places it is customary to offer worship to this "old man of the sky," on the nineteenth of the sixth moon, as that is his " birthday." But among a people who assign a " birthday" to the sun, it is superfluous to enquire who was the father of lao or when he was born, for on matters of this sort there is absolutely no opinion at all. It is difficult to make an ordinary Chinese understand that such questions have any practical bearing. He takes the tradition as he finds it, and never dreams of raising any enquiries upon this point or an/ other. We have seldom met any Chinese, who had an intelligible theory with regard to the antecedents or qualities of Jade Emperor, except that he is supposed to regulate the weather, and hence the crops. The wide currency among the Chinese people, of this term, hinting at a personality, to whom however, so far as we know, no temples are erected, and to whom no worship distinct from that to " heaven and earth" is offered, seems to remain thus far unexplained.

Lighting joss sticks

“As we have already had repeated occasion to point out, there is very little which one can be safe in predicating of the Chinese Empire as a whole. Of this truth the worship in Chinese temples is a conspicuous example. The traveller who lands in Canton, and who perceives the clouds of smoke arising from the incessant offerings to the divinities most popular there, will conclude that the Chinese are among the most idolatrous people in the world. But let him restrain his judgment until he has visited the other end of the Empire, and he will find multitudes of the temples neglected, absolutely unvisited except on the first and fifteenth of the moon, in many cases not then, and perhaps not even at New Year, when, if ever, the Chinese instinct of worship prevails. He will find hundreds of thousands of temples, the remote origin of which is totally lost in antiquity, and which are occasionally repaired, but of which the people can give no account, and for which they have no regard. He will find hundreds of square miles of populous territory, in which there is to be seen scarcely a single priest either Taoist or Buddhist. In these regions he will generally find no women in the temples, and the children allowed to grow up without the smallest instruction as to the necessity of propitiating the gods. In other parts of China, the condition of things is totally different, and the external rites of idolatry are interwoven into the smallest details of the life of each separate day.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE TEMPLES factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEMPLES, SACRIFICES AND RITES factsanddetails.com ; RELIGIOUS TAOISM, TEMPLES AND ART factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES, MONKS AND FUNERALS factsanddetails.com ; FOLK RELIGION IN CHINA: QI, YIN-YANG AND THE FIVE FORCES factsanddetails.com; RELIGION, DIVINATION AND BELIEFS IN SPIRITS AND MAGIC IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; GODS AND SPIRITUAL BEINGS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; SHAMANISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; QI AND QI GONG: POWER, QI MASTERS, BUSINESS AND MEDITATION factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Daoist Priests of the Li Family: Ritual Life in Village China” by Stephen Jones Amazon.com; Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of Southeast China (Princeton Legacy Library) by Kenneth Dean Amazon.com; “Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China” by James L. Watson and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com; Religions of China in Practice” by Donald S. Lopez Jr. Amazon.com “Shenism: Absolute Knowledge Of China's Earliest Folk Religion” by Eugene Alejandro Amazon.com; “Chinese Religion in Contemporary Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan: The Cult of the Two Grand Elders” by Fabian Graham Amazon.com; “In Search of the Folk Daoists of North China” by Stephen Jones Amazon.com; “Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits” by Red Pine Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Religions of China: The World As a Living System” by Daniel L. Overmyer Amazon.com; “Religion in China: Ties that Bind” by Adam Yuet Chau Amazon.com

Chinese Temple Practices

Busy Chinese temples are smokey places crowded with people lighting bouquets of smoking joss sticks, saying prayers, leaving jade orchid blossoms as offerings, throwing sheng bei (fortune-telling wooden blocks) and donating ghost money to variety of ancient gods in return for things like good luck on the lottery, good scores for children on important exams and good business.

Temples in China are not good places to visit if you have respiratory problems: burning incense coils, some of them 50-feet in length when unraveled, hang from the ceiling; joss sticks smoke away in urns; and pieces of ignited rice paper are tossed into the air by worshipers. Temple goers burn fake money for longevity and set fire to paper cars and TV sets at funerals. In 1995, the Chinese government banned the practice of burning money during ancestor worship ceremonies because the custom was officially deemed a fire hazard and a superstition. In January 2006, 36 people were killed in an explosion when devout Buddhists in the central province of Henan burned incense and prayed at a temple near warehouse storing firecrackers, igniting the fireworks.

Reporting from Beijing, Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: In the northern suburbs of this city is a small temple to a Chinese folk deity, Lord Guan, a famous warrior deified more than a millennium ago. Renovated five years ago at the government’s expense, the temple is used by a group of retirees who run pilgrimages to a holy mountain, schoolchildren who come to learn traditional culture and a Taoist priest who preaches to wealthy urbanites about the traditional values of ancient China. During a visit” there “I saw a dozen or so people, mostly in their 30s and 40s, reading works by Wang Yangming, a philosopher born in the late 15th century. On the face of it, this was in line with government policy: The party has embraced Wang for exemplifying an incorruptible spirit and matching words with deeds. But after reading a passage of Wang’s work, the men and women sat around a big wooden table, wielding brushes to write out, over and over again, his most famous phrase: “zhi xing he yi” (knowledge and action are one). This knowledge, according to Wang, comes from an inner light, a conscience — one that no government, no matter how powerful, can control. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, December 21, 2019; Johnson is the author of“The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao”]

Kowtows

kowtowing to an altar

K’o t’ous (kowtows) are bows performed as acts of worship. Worshipers at local temples for the Dragon King bow three times before an image of deity, place incense sticks before it, cast lots of numbered bamboo sticks and make donations. Pilgrims visiting temples sometimes line up and stop every few steps and bow.

Kowtowing was a kind of daily etiquette in the feudal society. According to the ancient book Zhouli Chunguan Dazhu, there were 9 kinds of kowtow, illustrating that the etiquette was popular as far back as in the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC-256 BC). In the following year of the Revolution of 1911 (also known as the Xinhai Revolution), Sun Yat-sen (first president and founding father of the Republic of China) abolished the etiquette. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “When the emperor worshipped at the Temple of Heaven, he worshipped through a ritual called the “three prostrations and nine kowtows.” The emperor would be commanded by a high-ranking bureaucrat to prostrate himself, which he would do. He would then be told to kowtow once, then to kowtow a second time, then a third time. Each time he did so, he would touch his head to the ground. (The word “kowtow” is an Anglicized rendering of the Chinese word ketou, meaning “to knock the head” against the ground.) The emperor would then be told to arise, then to prostrate himself again and begin another cycle of this sequence, which would have to be repeated a total of three times — three successive prostrations, each with three kowtows, for a total of nine kowtows. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos ]

“This ritual of the Three Prostrations and the Nine Kowtows was an important one, for it was also what an ordinary farmer would perform at the funeral of his father. Indeed, the phrase “from the imperial court down to our village” was commonly found in widely circulated documents during those days. People used this phrase again and again to express the interconnection and commonality amongst all Chinese people, regardless of social position.

“The fact that high government officials were commanding the emperor himself to kowtow during the ritual of the Three Prostrations demonstrates how these two key institutions — the imperial and the bureaucratic — were intertwined and in fact, interdependent. Consider that by the time of the Qing dynasty the governmental bureaucracy in China had already been around for hundreds of years. The ceremonies that the new Qing emperors were taking up were not invented by the Qing, or even the Ming who preceded them. These rituals were ancient, and the continuity of these rituals and the traditions they expressed were in the hands of an enduring bureaucracy.”

Joss Sticks

Joss sticks (incense sticks) have traditionally been an important component of Taoist religious practice. Worshippers believe the smoke helps waft prayers towards their deities. Today the sticks are also fixtures of Confucian and Buddhist worship. Sometimes they are even part of Christian rituals. Worshippers normally light three joss sticks in the courtyard of the house of worship, and place them in sand-filled containers or in specially prepared racks. Then moving to the center of the patio or pagoda front, they perform the prayers three times. "Money" made of golden or red crepe paper may also be burned at this time in an outdoor fire so that the ascending smoke may supply the needs of the spirits or gods. Unless specifically invited to do so, it is not proper for non-adherents of the faith to light joss sticks. [Source: The Religions of South Vietnam in Faith and Fact, US Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Chaplains Division,1967 ++]

Joss sticks and incense burners are found in family altars, spirit houses, and temple courtyards and before the figures of Buddha. Not all joss sticks are fragrant as some are primarily for smoke and have only the faintest odor. However, the more favored joss sticks are the ones with incense which serves both as a means of veneration and as a practical deodorizer. Few homes are without a joss stick to be utilized for some reason. Traditionally, joss sticks have been handmade. Basically the joss stick is made with a thin bamboo stick, which is painted red, Part of the stick is rolled in a putty-like substance-the exact formulae are guarded by their owners. ++

The putty-like substance is composed of the sawdust of such materials as sandalwood and other fragrant plants mixed with water or another evaporating liquid. Normally at least three different kinds of sawdust are mixed for the best result. The ideal woods for this sawdust come from the mountain forests and from Laos. Once the sticky brown mixture is placed on 1/3 or more of the painted bamboo stick, it is placed in the drying racks in the sun. It takes about two days of sunshine to dry the mixture satisfactorily, and then these are brought indoors and placed so that several additional days of drying time is allowed. This helps to insure that all moisture has evaporated and makes a firmer better product.

Once completed, the joss sticks may be placed into packages along with a couple of candles for the altar, or placed loosely in larger boxes for wholesale or retail distribution. Most of the work is done by girls, who, with training and practice, can make about three thousand joss sticks a day. It is possible for a hard worker to earn perhaps the equal of a dollar for a full day's labor. ++

Joss sticks are very reasonably priced, and it is good for the common people that this is so, for few acts of devotion could be complete without the lighting of joss sticks. These may be placed in sand-filled containers either in the temple courtyard or in racks located in front or on top of an altar. Sometimes after burning joss sticks are placed in front of a Buddha statue, the ascending smoke from the burning joss stick is thought by some to have beneficial aid in pleasing that power to whom worship is made, or prayers offered. ++

It is possible to purchase spiral or circular joss sticks which will burn as long as one to three months with incense and smoke being cast off night and day. Quite often walls, the ceiling and sometimes the figures of devotion or veneration are smoked or darkened. Where the buildings do not have adequate ventilation, the spaces above the doorway level may be perpetually gray with smoke. The overwhelming fragrance of the burning joss sticks may also cloak any unpleasant odors that might detract the worshipper from his devotion, or which could offend the one to whom petitions are being made. ++

Chinese Spirit Tablets

spirit tablet

According to the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Missouri: “Chinese religion, with its complex blend of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and folk traditions, involves a wide variety of practices and related paraphernalia. Spirit tablets are one type of ritual object commonly seen in temples and shrines and on household altars. Usually of wood, these small plaques bear inscriptions honoring ancestors, gods, and other important figures. [Source: Ancestral Tablet,Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri ]

“Ancestor worship, which is found in many forms in cultures throughout the world, has long been a key religious belief and practice in China. Throughout China, ancestors have traditionally been worshipped with sacrifices, shrines, and ancestor tablets. Ancestor tablets vary in size and shape in different parts of the country, but typically consist of a one- or two-piece tablet set up on a pedestal. The tablets are inscribed with the title and name of the deceased, dates of birth and death, and additional information such as place of burial and the name of the son who erects the tablet.

“The customs involved in installing ancestor tablets in the family shrine also vary by region, although there are some common practices. Often two tablets are made – one of paper and one of wood. A ceremony takes place in which the ancestor’s spirit is transferred to the wooden tablet. Once the transfer is successful, the paper tablet is either burned or buried with the dead person. After the funeral service, the tablet is taken back to the family’s house and housed in a shrine. There are usually three shrines for ancestor tablets per house. The center shrine is reserved for the primary family ancestor, or Shin Chu, who is placed in the middle of the shrine. The rest of the middle shrine is filled with the next most important family members. All the other male family members’ tablets are housed in the other two shrines; occasionally their wives’ tablets join them.

“In addition to ancestor tablets, there are also spirit tablets devoted to the host of deities that preside over the cosmos. These are placed in temples or wayside shrines and serve to honor these figures and to protect the community. This online exhibit presents ancestor tablets and general spirit tablets collected in China in the early 20th century.”

Burning of Votive Paper Objects

burning joss paper

Temples of ancestor worship normally have a fire into which worshippers throw money made of tissue-like paper. History reveals that in times past, when a member of royalty died, and was buried, living persons were often buried along with him so that he might still be waited upon by servants. His personal possessions were often included in this rite. Such customs seem to have been practiced in many lands. In at least one land, the widow was also slain and cremated when the husband died, so that he might have a wife in the "next world". This custom was condemned by Confucius as being inhuman. [Source: The Religions of South Vietnam in Faith and Fact, US Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Chaplains Division,1967 ++]

Feeling that such a custom might be unkind, or at least expensive, someone came up with the idea of using wooden or straw figures, representing common objects used in the persons lifetime. These figures were burned or buried with the deceased. Incidentally, such burial customs have provided archeologists with valuable information of bygone ages. According to tradition, about the first century B.C. a government official developed the idea of making votive offerings from the bark of a palm tree. These were used to imitate silver, gold, clothing, common objects, and could be burned as an offering during the funeral in place of valuable objects or human beings. ++

Vuong-Du, the legendary inventor of the votive paper idea, was apparently not able to sell much of his product. But then struck by a "clever" idea, he decided upon a surefire gimmick to sell his product. By agreement with his fellow-makers of votive paper, he arranged for one of his sickly companions to be put to bed and told everyone that he was seriously ill, and a few days later that he was dead. Placed in a coffin (with a previously bored air hole) the funeral proceeded toward the tomb accompanied by a great number of figurines made of votive paper. Just as the heavy coffin was to be lowered into the tomb, the "dead" man was heard to groan and moan; then as the lid was raised, the haggard and pale "corpse" sat up and spoke to the mourners. He told them that while he had been taken to the Infernal Regions (Hell), he had been released because his family had substituted money and paper figures for his person. Apparently, the story was believed at the time, for sales boomed as many hurried to buy these votive items and burn them to the spirits of their ancestors. ++

Regardless of the truth of this legend which is recorded in a number of documents, the burning of votive paper seems to constitute one of the essential rites in homage or worship to the dead. In the courtyard or temples where worshippers may be found will be seen an open fire into which the worshipper casts votive objects including paper money as a part of their worship. Such votive paper, along with joss sticks and candles, can be purchased for a very small fee either on the sidewalk or in front of the temple, or sometimes in the temple itself. Votive paper burning in Vietnam preceded the arrival of Chinese colonists in the first centuries of the present era according to some students of culture. ++

Chinese Paper Gods

Hungry Ghost Festival paper gods

Paper god images are divided initially by usage: Those which were purchased to be burned immediately and serve as emissaries to heaven; and those which were purchased to be displayed for a year while offering protection to the family in a variety of ways, before being burned. The images are further divided by display locations and by the deities they represent. The prints included in this category would be pasted conspicuously throughout the home during the New Year's celebration and displayed throughout the year. At the end of the year, they were burned and replaced with a fresh print. These prints are generally more colorful and exquisitely designed than those intended for ceremonial use.[Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University columbia.edu ]

The majority of the prints in ceremonial use category formed part of a ceremony during which they would receive offerings and then be sent off by burning to the other realm to intercede there on behalf of those remaining behind. Others would be pasted on ceremonial altars, in stables, or other relatively inconspicuous places, where they would receive offerings for a period of time before being burned.

Colorful front door prints, usually produced in pairs, were pasted on adjacent double doors, side-by-side on a single door, or on the walls around the front door. Although they originally depicted fearsome gods who would chase away demons, they later came to include gentler images that promised prosperity and good tidings for the household., Back door prints, often depicting Zhong Kui, were placed near the back door to ensure that no demons would sneak in unnoticed by the guards of the front door.

The Kitchen (Stove) God, often depicted with his wife, was on duty in the kitchen throughout the year, keeping watch over the family. At the end of the year, he received ample offerings, and after his immolation he would return to heaven to report on the family. A yearly calendar was often included on prints of the Stove God. Bedroom door prints, which usually portray double happiness or happy children, were pasted on or near the bedroom door. They would assist the happy couple in their pursuit of progeny, encouraging especially the birth of sons.

Domestic shrines often featured colorful and elaborate depictions of the God of Wealth. They were likely displayed throughout the year to ensure prosperity, or at least financial stability. Some of these were produced in pairs like the door prints, and may have been displayed on or around a doorway rather than in a shrine.

Ceremonial Use Paper Gods

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: The majority of the prints used in ceremonies “formed part of a ceremony during which they would receive offerings and then be sent off by burning to the other realm to intercede there on behalf of those remaining behind. Others would be pasted on ceremonial altars, in stables, or other relatively inconspicuous places, where they would receive offerings for a period of time before being burned. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University columbia.edu ]

Pantheon prints — some of them enormous — depict "all the gods." “Although the inclusion and positioning of gods does vary from print to print, a number of norms surface after careful comparison. These norms, as well as the inconsistencies among the prints, can tell us a lot about the ways in which the realm of the gods was ordered. The subsections are arranged in a manner that corresponds roughly with the usual arrangement of the gods in the pantheons.

“Buddhas and bodhisattvas occupy an honored position, usually in the uppermost row of the pantheon. There does not, however, seem to be a clear hierarchy among them, and while Guanyin seems to be the most frequently represented in individual prints, she is not generally a central figure in the pantheon. The God of Wealth is included in almost every pantheon, and is well represented in individual prints. This group of prints of the God of Wealth seems to have been intended for ceremonial use rather than display, as were those images of the God of Wealth under "Domestic Shrine."

“Guandi and the Jade Emperor occupy the two most prominent positions in the majority of the pantheons. They are usually found in the center of the pantheon, and the figures that represent them are almost always significantly larger than the other gods. In addition, Guandi can be recognized by his red face. Heaven prints consists of gods that are associated with heaven in some way or another, but that in practice are not easily distinguished from the following category, "Earth." Many of the heavenly gods are anthropomorphic stars that are occasionally referred to by their titles (in characters) alone. In the pantheons, these gods are located along the midline, near Guandi.

The Earth God category is perhaps the most diverse and inclusive of the prints for ceremonial use. It includes all the gods in charge of the natural world (including mountains, water, animals, etc.) as well as those associated with specific pursuits or trades, such as Wenshu, the God of Literature. In the pantheons, these gods are usually located just below the gods associated with heaven. Underworld gods make up the bottom row of the pantheon. They are in charge of hell and care for the newly dead, and ancestors more generally. Also included among the individual prints are images of clothing and money to be burned for use by the deceased in the underworld.”

Mountains and Religion in China

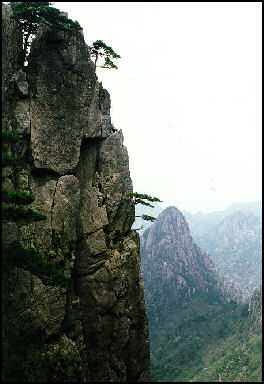

Huangshan, one of China's most sacred mountains

Sacred Mountains in China include 1) Tai Shan in Shandong Province; 2) Huang Shan in Anhui Province; 3) Jiuhua Shan in Anhui Province; 4) Wutai Shan in Shanxi Province; 5) Putuoshan in Zhejaing Province; 6) Emei Shan in Sichuan Province; 7) Song Shan in Henan Province; 8) Heng Shan in Hunan Province.

Sacred Mountains: Name — Location — Height — Religion

Bei Heng Shan — Shanxi Province — 3,060 meters (10,095 feet) — Taoism

Nan Heng Shan — Hunan Province — 1,282 meters (4,232 feet) — Taoism

Hua Shan — Shanxi Province — (along the Yellow River) — 1,985 meters (6,552 feet) — Taoism

Song Shan — Henan Province — (along the Yellow River) — 1,485 meters (4,900 feet) — Taoism

Tai Shan — Shandong Province — 1,530 meters (5,069 feet) — Taoism

Emei Shan — Sichuan Provnice 3,060 meters (10,095 feet) — Buddhism

Jiuhua Shan — Anhui Province — 1,322 meters (4,340 feet) — Buddhism

Putuo Shan — Zhejiang Province — 282 meters (932 feet) — Buddhism

[Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of Physical Geography, Gale Group, Inc., 2003]

Huangshan is important in China's religions. The Kun-lun Shan, a range of mountains in northern Tibet, is where Taoists believe paradise can be found. The Kimkang mountains in Tibet are an important pilgrimage site for Buddhists. China has five sacred mountains, and many Chinese hope that in their lifetime they can climb all five. Most of these mountains have stairways to the summit, where there are nice views and noodle stands and postcards-selling monks.

Taishan (near Qufu) is China's most sacred mountain and one of China's most popular tourist sites. Revered by Taoists and Confucians, it covers an area of 426 square kilometers and is 4,700 feet high. Many emperors came here to make offerings and pray to heaven. Poets and philosophers drew inspiration from it. Pilgrims prayed on an alter said to be the highest in China.

Confucius is said to have climbed Taishan and proclaimed “I feel the world is much smaller” when he reached the top. The Emperor Wu Di ascended it in his quest for immortality. Taishan means “big mountain” or “exalted mountain” It is the eastern peak among the five holy mountains associated with the cult of Confucius. The five peaks represent the directions — north, south, east, west and central — and Taishan is considered the holiest because it is in the east, the direction from which the sun rises. For many Chinese it is like Mecca. Climbing it is as much a nationalist and spiritual experience as a recreational one.

Celestial Immortal Holy Mother of Miaofengshan

Calum MacLeod wrote in The Times: “Zhao Baoqi, a martial arts master, was losing a bout with illness. He had spent 32 days in intensive care when a dozen of his friends and disciples trekked to a holy site in the hills outside Beijing seeking help from the Celestial Immortal Holy Mother of Miaofengshan.She saved his life, it is said, and for each of the past five years he has returned in the spring to pay his respects, and to lead other stick-fighters in a carnival-like pilgrimage. The event highlights the return of religion and Chinese tradition to a society whose ruling Communist Party retains a deep suspicion of faith and spirituality. [Source: Calum MacLeod, The Times, May 22, 2017]

Thousands of pilgrims visited Miaofengshan — the Mountain of the Marvellous Peak — 40 miles west of the Chinese capital this month to pray at the shrines and be entertained. Strongmen balanced heavy poles or tossed huge vases, performers cracked whips and cross-dressers paraded with bras outside their shirts. The “Immortal Stilts” troupe had to call off their act this time — “only four of us showed up in costume”, one apologised — and some of the lion dancers needed more practice, Mr Zhao, 64, said but he welcomed all their noisy efforts. We have to preserve these traditions. All the other temple fairs in Beijing at Chinese New Year are fake. Only this one is traditional, and attracts whole-hearted troupes and pilgrimage associations. It’s a matter of faith,” he added. The Holy Mother, a Taoist goddess, shares her temple with Buddhist and Confucian shrines and is known for boosting fertility. “If you want kids, this really works,” swore a stall vendor, offering a doll for £7 to present at the altar. “My sister-in-law got pregnant after doing this last year.”

“Famous since the 17th century, the Miaofengshan temple complex was destroyed during Mao’s Cultural Revolution when he mobilised the masses to eradicate religion. Only a single white pagoda “was too strong” for the wrecking gangs, claims a sign beside it. Long hidden, the people’s faith proved durable too. Ni Jintang, boasting a beard but no moustache, recalled his father’s role in reviving the Miaofengshan pilgrimage associations in the 1990s, as the temples were rebuilt.

“His Whole Heart Philanthropic Salvation Tea Association is among 80 groups now providing sustenance to pilgrims — free “sacred” tea, steamed buns and porridge — or venerating the shrines through performance. “Pilgrims feel they will bring good fortune,” said Mr Ni, a property developer who took leave for the full 16-day pilgrimage. “I have several disciples. We can definitely pass on these traditions to future generations.”

“The pilgrimage “shows how China’s religious revival was largely unexpected by the government,” said Ian Johnson, who tells the Ni family story in his new book Souls of China. “These groups are self-organising and self-financing. Like much of China’s religious life it’s been created by ordinary people trying to reconnect with some sort of higher values, such as community.” Mei Weijun, a silk clothing salesman, drove 280,000 steamed buns to the peak in his four-wheel-drive vehicle. Cooked to order by a trusted company, each had the character for good fortune stamped on it. “We want everybody to be healthy and at peace,” he said. “If you have good fortune, then you will have everything else too.” After burning incense and kowtowing at several altars, Cheng Jinmei, an office worker, and her 12-year-old daughter prepared to return to the city, taking with them holy buns for her parents. “I’ve come every year since she was born, and always request the same thing — good health for our family,” Mrs Cheng, 42, said. “In China there’s no need to distinguish between Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian. This temple is known to be highly efficacious. If you ask, there will be a response.”

Religion Societies in 19th Century China

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “The genius of the Chinese for combination is nowhere more conspicuous than in their societies which have a religious object. Widely as they differ in the special purposes to which they are devoted, they all appear to share certain characteristics, which are generally four in number—the contribution of small sums at definite intervals by many persons; the superintendence of the finances by a very small number of the contributors; the loan of the contributions at a high rate of interest, which is again perpetually loaned and re-loaned so as to accumulate compound interest in a short time and in large amounts; and lastly, the employment of the accumulations in the religious observance for which the society was instituted, accompanied by a certain amount of feasting participated in by the contributors. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg. Smith (1845 –1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang,a village in Shandong.]

“The countless secret sects of China, are all of them examples of the Chinese talent for coöperation in the alleged “practice of virtue.” The general plan of procedure does not differ externally from that of a religious denomination in any Western land, except that there is an element of cloudiness about the basis upon which the whole superstructure rests, and great secrecy in the actual assembling at night. Masters and pupils, each in a graduated series, manuscript books containing doctrines, hymns which are recited or even composed to order, prayers, offerings, and ascetic observances are traits which many of these sects share in common with other forms of religion elsewhere. They have also definite assessments upon the members at fixed times without which, for lack of a motive power, no such society would long hold together.

See Rain Gods and Rituals in 19th Century China Under RAINMAKING AND MAN-MADE WEATHER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Mountain Pilgrimage Societies in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”:“A typical example of the numerous societies organized for religious purposes may be found in one of those which have for their object a pilgrimage to some of the five sacred mountains of China. The most famous and most frequented of them all is the Great Mountain (Tai Shan) in Shandong, which in the second month of the Chinese year is crowded with pilgrims from distant parts of the empire. For those who live at any considerable distance from this seat of worship, which according to Dr. Williamson is the most ancient historical mountain in the world, the expense of travel to visit the place is an obstacle of a serious character. To surmount this difficulty, societies are organized which levy a tax upon each member, of (say) one hundred cash a month. If there are fifty members this would result in the collection of 5,000 cash as a first 4payment. The managers who have organized the society, proceed to loan this amount to some one who is willing to pay for its use not less than two or three per cent. a month. Such loans are generally for short periods, and to those who are in the pressing need of financial help. When the time has expired, and principal and interest is collected, it is again loaned out, thus securing a very rapid accumulation of capital. Successive loans at a high rate of interest for short periods, are repeatedly effected during the three years, which are generally the limit of the period of accumulation. It constantly happens that those who have in extreme distress borrowed such funds, find themselves unable to repay the loan when it is called in, and as benevolence to the unfortunate forms no part of the “virtue practice” of those who organize these societies, the defaulters are then obliged to pull down their houses or to sell part of their farms to satisfy the claims of the “Mountain Society.” Even thus it is not always easy to raise the sum required, and in cases of this sort, the unfortunate debtor may even be driven to commit suicide.

““Mountain Societies” are of two sorts, the “Travelling,” (hsing-shan hui), and the “Stationary,” (tso-shan hui). The former lays plans for a visit to the sacred mountain, and for the offering of a certain amount of worship at the various temples there to be found. The latter is a device for accomplishing the principal results of the society, without the trouble and expense of an actual visit to a distant and more or less inaccessible mountain peak. The recent repeated outbreaks of the Yellow River which must be crossed by many of the pilgrims to the Great Mountain, have tended greatly to diminish the number of “Travelling Societies,” and to increase the number of the stationary variety.

“When the three years of accumulation have expired, the managers call in all the money, and give notice to the members who hold a feast. It is then determined at what date a theatrical exhibition shall be given, which is paid for by the accumulation of the assessments and the interest. If the members are natives of several different villages, a site may be chosen for the theatricals convenient for them all, but without being actually in any one of them. At other times the place is fixed by lot.

“The “travelling” like the “sitting” society gathers in its money at the end of three years, and those who can arrange to do so, accompany the expedition which sets out soon after New Year for the Great Mountain. The expenses at the inns, as well as those of the carts employed, are defrayed from the common fund, but whatever purchases each member wishes to make must be paid for with his own money. On reaching their destination, another in the long series of feasts is held, an4 immense quantity of mock money is purchased and sent on in advance of the party, who are sure to find the six hundred steps of the sacred mount, (popularly supposed to be “forty li” from the base to the summit), a weariness to the flesh. At whatever point the mock money is burnt, a flag is raised to denote that this end has been accomplished. By the time the party of pilgrims have reached this spot, they are informed that the paper has already been consumed long ago, the wily priests taking care that much the larger portion is not wasted by being burnt, but only laid aside to be sold again to other confiding pilgrims.

“If any contributor to the travelling society, or to any other of a like nature, should be unable to attend the procession to the mountain, or to go to the temple where worship is to be offered, his contribution is returned to him intact, but the interest he is supposed to devote to the virtuous object of the society, for he never sees any of it.

Temple Fairs and Stationary Mountain Pilgrimage Societies

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “During the performance of the theatricals, generally three days or four, the members of the society are present, and may be said to be their own guests and their own hosts. For the essential part of the ceremony is the eating, without which nothing in China can make the smallest progress. The members frequently treat themselves to three excellent feasts each day, and in the intervals of eating and witnessing theatricals, they find time to do more or less worshipping of an image of the mountain goddess (T‘ai Shan niang-niang) at a paper “mountain,” which by a simple fiction is held to be, for all intents and purposes, the real Great Mountain. While there does not appear to be any deeply-seated conviction that there is greater merit in actually going to the real mountain than in worshipping at its paper representative at home, this almost inevitable feeling certainly does exist, and it expresses itself forcibly in nicknaming the stationary kind “squatting and fattening societies” (tun-piao hui). But while the Chinese are keenly alive to the inconsistencies and absurdities of their practices and professions, they are still more sensible of the delights of compliance with such customs as they happen to possess, without a too close scrutiny of “severe realities.” The religious societies of the Chinese, faulty as they are from whatever point of view, do at least satisfy many social instincts of the people, and are the media by which an inconceivable amount of wealth is annually much worse than wasted. It is a notorious fact, that some of those which have the largest revenues and expenditures, are intimately connected with gambling practices. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

“Many large fairs, especially those held in the spring, which is a time of comparative leisure, are attended by thousands of4 persons whose real motive is to gamble with a freedom and on a scale impossible at home. In some towns where such fairs are held, the principal income of the inhabitants is derived from the rent of their houses to those who attend the fair, and no rents are so large as those received from persons whose occupation is mainly gambling. These are not necessarily professional gamblers, however, but simply country people who embrace this special opportunity to indulge their taste for risking their hard-earned money. In all such cases it is necessary to spend a certain sum upon the underlings of the nearest yamên, in order to secure immunity from arrest, but the profits to the keeper of the establishment (who generally does not gamble himself) are so great, that he can well afford all it costs. It is probably a safe estimate that as much money changes hands at some of the large fairs in the payment of gambling debts, as in the course of all the ordinary business arising from the trade with the tens of thousands of customers. In many places both men and women meet in the same apartments to gamble (a thing which would scarcely ever be tolerated at other times), and the passion is so consuming that even the clothes of the players are staked, the women making their appearance clad in several sets of trousers for this express purpose!

“The routine acts of devotion to whatever god or goddess may be the object of worship are hurried through with, and both men and women spend the rest of their time struggling to conquer fate at the gaming-table. It is not without a certain propriety, therefore, that such fairs are styled “gambling fairs.”

Image Sources: 7) Temple, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html; 8) Temple construction, kowtowing child and joss sticks, beifan.com, Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021