MANCHU CONQUESTS AND EXPANSION

Kangxi and the pacification of the Dzungars

The Manchus of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) expanded Chinese control to it greatest extent in Central and Southeast Asia and also brought Tibet and Mongolia under Chinese control. Conquests in the 18th century in western and southern China nearly doubled China's size. In doing this the Qing Dynasty created a wide corridor, connecting many different peoples and cultures under their rule and beyond.

Manchu expansion into the West started in 1760, dramatically increasing the population of the empire and providing a "buffer for the heartland." In less than 70 years (between 1762 and 1830) the population of China nearly doubled, from 200 million people to 395 million people. The empire was expanded to the west and south by granting trade concessions to Islamic rulers in Central Asia and monarchs in Southeast Asia.

The Qing regime was determined to protect itself not only from internal rebellion but also from foreign invasion. After China Proper had been subdued, the Manchus conquered Outer Mongolia (now the Mongolian People's Republic) in the late seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century they gained control of Central Asia as far as the Pamir Mountains and established a protectorate over the area the Chinese call Xizang but commonly known in the West as Tibet. The Qing thus became the first dynasty to eliminate successfully all danger to China Proper from across its land borders. Under Manchu rule the empire grew to include a larger area than before or since; Taiwan, the last outpost of anti-Manchu resistance, was also incorporated into China for the first time. In addition, Qing emperors received tribute from the various border states. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

The chief threat to China's integrity did not come overland, as it had so often in the past, but by sea, reaching the southern coastal area first. Western traders, missionaries, and soldiers of fortune began to arrive in large numbers even before the Qing, in the sixteenth century. The empire's inability to evaluate correctly the nature of the new challenge or to respond flexibly to it resulted in the demise of the Qing and the collapse of the entire millennia-old framework of dynastic rule. *

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu ; Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; MANCHUS — THE RULERS OF THE QING DYNASTY — AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; KANXI (ruled 1662–1722) factsanddetails.com; YONGZHENG EMPEROR (ruled 1722-1735) factsanddetails.com; QIANLONG EMPEROR (ruled 1736–95) factsanddetails.com; QING LIFE factsanddetails.com; QING GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com; QING- AND MING-ERA ECONOMY factsanddetails.com; MING-QING ECONOMY AND FOREIGN TRADE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE SHIPS, SEA DEFENSES AND MARITIME TRADE IN THE QING DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; QING-ERA CHINESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com; PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under the Qing Dynasty” by Joanna Waley- Amazon.com; The Army of the Manchu Empire: The Conquest Army and the Imperial Army of Qing China, 1600-1727 by Michael Fredholm von Essen Amazon.com; “China's Last Empire: The Great Qing” by William T. Rowe and Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: The Ch'ing Dynasty, Part 1: To 1800" by Willard J. Peterson Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Part 2" by Willard J. Peterson Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 11: Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911, Part 2" by John K. Fairbank and Kwang-Ching Liu Amazon.com; “Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of K'ang-His” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com; “The Brilliant Reign of the Kangxi Emperor: China's Qing Dynasty” by Hing Ming Hung Amazon.com; “Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World” by Mark Elliott and Peter N. Stearns Amazon.com; “Splendors of China's Forbidden City: The Glorious Reign of Emperor Qianlong” by Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson Amazon.com; “The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture” by Richard J. Smith Amazon.com; "The Last Emperors: A Social History of the Qing Imperial Institutions" by Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com

Qing Military

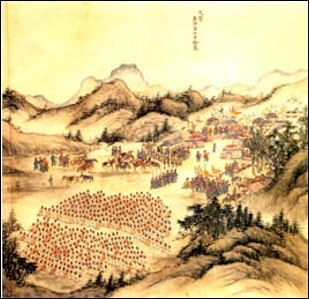

Qing soldiers around 1900According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “From the sudden rise of Nurhaci, founder of the Manchu state and grandfather of the first Qing emperor, to the collapse of the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century, there was hardly a single day in which imperial military forces were not engaged in some part of the empire or its surrounding borderlands. Among the campaigns were the pacification of the Dzunghars, Muslims, Chin-ch'uan (western Sichuan), the Lin Shuang-wen Rebellion (in Taiwan), Annam, Nepal, and the T'ai-p'ing Rebellion. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Prior to the establishment of the Qing, the Manchus, in their vie for the throne of China, engaged the forces of the Ming dynasty in a long war of epic scale. This war culminated in the Sa-erh-hu and Sung-shan campaigns, which demonstrated the field and siege capabilities of the Manchu bannermen. After crossing the Great Wall and seizing Peking, the Qing organized the so-called "Army of the Green Standard," composed of native Chinese soldiers, which in turn enabled their conquest of central and southern China. Under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1736-1795), the military further expanded and fortified the borders of the empire. The middle years of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign denote the high water mark of the Qing military. By the end of 18th century, its long decline was already underway. Beginning in the Tao-kuang reign (1821-1850), military encroachment by Western imperial powers led to a long series of Qing defeats and the eventual downfall of the dynasty. \=/

“During the early years of the dynasty, the Qing possessed a large and elite cavalry force. In open combat, these troops utilized a diverse and spirited array of assault and flanking maneuvers, powerful and accurate mounted archery, and awe-inspiring charging tactics. When besieging cities, the early Manchu emperor T'ai-tsung (1627-43) relied primarily on excellent cannon. This powerful combination of cavalry and firearms was maintained until the late 18th century. In military illustrations of the era, one can see the use of mounted archery, cavalry charges, and explosive projectiles, as appropriate, in open battle, sieges, and assaults on fortified positions. It was only with the Opium War (1840-42) and the conflicts of the subsequent decades that the power of the Qing military failed in the face of the advanced firearms, warships, and modern tactics of the Western imperial powers\=/

“The success and failure of the Qing military was closely linked to the factors of military power, strategy, military technology, and the quality of its officer corps. The success of the Manchu bannermen in the early years of the dynasty was primarily due to the skill of their cavalry and their possession of firearms. The infusion of Western technology during the Shun-chih (1644-1661) and K'ang-hsi (1662-1722) reigns enabled the Qing to further develop their firearms technology. However, during the mid and latter part of the 18th century, the government shifted to a closed and defensive military policy that hailed an end to advances in military thought, weaponry, and strategy. \=/

“This shift coincided, disastrously for the Chinese, with the scientific and technological surge of Western civilization. The crushing defeat inflicted by British imperial forces in the Opium War and other conflicts of the mid-19th century forced the Qing court to recognize the flaws and weakness of the Banner and Green Standard armies. In an anxious effort to place the military on par with that of the Western powers, the Qing established the Hsiang and Huai armies, founded naval facilities, and constructed the Northern and Southern navies. Yet the effort was too little, too late. Although the Qing succeeded in suppressing the Taiping Rebellion of the 1850s and 60s, they were soundly defeated by the Japanese army in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. The reasons for the fall of the Qing are many, yet from a military perspective, they can be summarized simply as the failures of weaponry, preparation, and leadership.” \=/

“During the early years of the Qing dynasty, the Banner cavalry relied primarily on mounted archery and charging tactics. Beginning in the reign of the T'ai-tsung emperor (1627-43), as the attentions of the Qing military shifted to assaults on walled cities and other fortifications, the army made increasing use of excellent cannon. Thus, the first half of the Qing dynasty saw the mixed use of both traditional weaponry and firearms. However, by the 18th century, the development of explosives stagnated and gradually fell behind the military technology innovations of the West. The resulting technological superiority of the European militaries was one of the key reasons for the military debacles suffered by the Qing in the 19th century. \=/

Qing Imperial banners

Qing Military Organization and Defense

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “During the early conquests of the dynasty, the Manchu military was composed of eight individual armies, each distinguished by a colored banner. These were the Eight Banners, and the soldiers in them, the so-called "bannermen." After crossing the Great Wall and seizing the capital, the Qing reorganized the surrendered remnants of the Ming military into the "Army of the Green Standard." Together, the Banner and Green Standard armies reunified China, expanded the frontiers of the empire, and reestablished firm defensive measures for the state. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“In the beginning, the Banner cavalry was primarily armed with bows, spears, and knives. During the reign of T'ai-tsung (1627-43), the army began to incorporate artillery units. The large-scale production of firearms continued through the Shun-chih (1644-61) and K'ang-hsi (1662-1722) reigns, substantially enhancing the military might of the imperial forces. However, the development of munitions gradually ground to halt during the Yung-cheng (1723-35) and Qianlong (1736-95) periods, and Chinese weapons technology fell far behind that of the West. \=/

“At the same time, the Banner armies were gradually becoming sinicized and losing their traditions of martial prowess, while corrupt leadership was taking its toll on the quality of training received by the Green Standard forces. In both cases, these armies suffered repeated losses in the Opium War and T'ai-p'ing Rebellion. As a result, the Qing government was forced to rely on the Hsiang and Huai armies (trained and commanded by Tseng Kuo-fan and Li Hung-chang, respectively) to put down the T'ai-p'ings and bring order to the state. In the wake of the assaults by joint British and French forces between 1856 and 1860, the Qing court began to take efforts to construct a modern navy. Yet the resulting Fukien and Northern navies were totally decimated by the Sino-French (1883-85) and Sino-Japanese (1894-95) wars, respectively. These losses led to the adoption of a new and reformed military system at the turn of the twentieth century.” \=/

“The Manchu's successful use of military power to conquer China gave them a strong appreciation for the importance of defense. They fortified major cities and other strategic points in the empire's transportation network, and bolstered these defenses with detachments of the Banner and Green Standard armies. They constructed gun emplacements along the coastline, which they staffed with naval units. In Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and other frontier areas, the government established outposts to protect and keep watch on the borderlands. They also built a network of courier routes and stations that spanned the empire, dispatched military units on regular tours of inspection, and maintained a constant flow of written memoranda between the capital and provincial officials; all in an effort to ensure that, despite the often great distance between the central and provincial governments, local authorities were kept firmly within the administrative apparatus of the state. The courier stations in the distant west, beyond the end of the Great Wall at Chia-yu-kuan, also served as watchtowers. \=/

See Banner System Under the Manchus

Qianlong's Victorious Return

Expansion and Pacification of the Qing Empire Under Kangxi

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The rise of the Qing Dynasty actually began under the Kangxi rule (1663-1722). The emperor had three tasks. The first was the removal of the last supporters of the Ming dynasty and of the generals, such as Wu Sangui, who had tried to make themselves independent. This necessitated a long series of campaigns, most of them in the south-west or south of China; these scarcely affected the population of China proper. In 1683 Formosa was occupied and the last of the insurgent army commanders was defeated. It was shown above that the situation of all these leaders became hopeless as soon as the Manchus had occupied the rich Yangtze region and the intelligentsia and the gentry of that region had gone over to them. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“A quite different type of insurgent commander was the Mongol prince Galdan. He, too, planned to make himself independent of Manchu overlordship. At first the Mongols had readily supported the Manchus, when the latter were making raids into China and there was plenty of booty. Now, however, the Manchus, under the influence of the Chinese gentry whom they brought, and could not but bring, to their court, were rapidly becoming Chinese in respect to culture. Even in the time of Kangxi the Manchus began to forget Manchurian; they brought tutors to court to teach the young Manchus Chinese. Later even the emperors did not understand Manchurian! As a result of this process, the Mongols became alienated from the Manchurians, and the situation began once more to be the same as at the time of the Ming rulers. Thus Galdan tried to found an independent Mongol realm, free from Chinese influence.

“The Manchus could not permit this, as such a realm would have threatened the flank of their homeland, Manchuria, and would have attracted those Manchus who objected to sinification. Between 1690 and 1696 there were battles, in which the emperor actually took part in person. Galdan was defeated. In 1715, however, there were new disturbances, this time in western Mongolia. Tsewang Rabdan, whom the Chinese had made khan of the Ölöt, rose against the Chinese. The wars that followed, extending far into Turkestan (Xinjiang) and also involving its Turkish population together with the Dzungars, ended with the Chinese conquest of the whole of Mongolia and of parts of eastern Turkestan. As Tsewang Rabdan had tried to extend his power as far as Tibet, a campaign was undertaken also into Tibet, Lhasa was occupied, a new Dalai Lama was installed there as supreme ruler, and Tibet was made into a protectorate. Since then Tibet has remained to this day under some form of Chinese colonial rule.

Wars and Conflicts with Neighboring Groups and States in Qing Period

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “During the Yongzheng period there was long-continued guerrilla fighting with natives in south-west China. The pressure of population in China sought an outlet in emigration. More and more Chinese moved into the south-west, and took the land from the natives, and the fighting was the consequence of this. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“At the beginning of the Qianlong period (1736-1796), fighting started again in Turkestan (Xinjiang). Mongols, now called Kalmuks, defeated by the Chinese, had migrated to the Ili region, where after heavy fighting they gained supremacy over some of the Kazakhs and other Turkish peoples living there and in western Turkestan. Some Kazakh tribes went over to the Russians, and in 1735 the Russian colonialists founded the town of Orenburg in the western Kazakh region. The Kalmuks fought the Chinese without cessation until, in 1739, they entered into an agreement under which they ceded half their territory to Manchu China, retaining only the Ili region. The Kalmuks subsequently reunited with other sections of the Kazakhs against the Chinese. In 1754 peace was again concluded with China, but it was followed by raids on both sides, so that the Manchus determined to enter on a great campaign against the Ili region. This ended with a decisive victory for the Chinese (1755). In the years that followed, however, the Chinese began to be afraid that the various Kazakh tribes might unite in order to occupy the territory of the Kalmuks, which was almost unpopulated owing to the mass slaughter of Kalmuks by the Chinese. Unrest began among the Muslims throughout the neighboring western Turkestan, and the same Chinese generals who had fought the Kalmuks marched into Turkestan and captured the Muslim city states of Uch, Kashgar, and Yarkand.

“The reinforcements for these campaigns, and for the garrisons which in the following decades were stationed in the Ili region and in the west of eastern Turkestan, marched along the road from Beijing that leads northward through Mongolia to the far distant Uliassutai and Kobdo. The cost of transport for one shih (about 66 lb.) amounted to 120 pieces of silver. In 1781 certain economies were introduced, but between 1781 and 1791 over 30,000 tons, making some 8 tons a day, was transported to that region. The cost of transport for supplies alone amounted in the course of time to the not inconsiderable sum of 120,000,000 pieces of silver. In addition to this there was the cost of the transported goods and of the pay of soldiers and of the administration. These figures apply to the period of occupation, of relative peace: during the actual wars of conquest the expenditure was naturally far higher. Thus these campaigns, though I do not think they brought actual economic ruin to China, were nevertheless a costly enterprise, and one which produced little positive advantage.

“In addition to this, these wars brought China into conflict with the European colonial powers. In the years during which the Chinese armies were fighting in the Ili region, the Russians were putting out their feelers in that direction, and the Chinese annals show plainly how the Russians intervened in the fighting with the Kalmuks and Kazakhs. The Hi region remained thereafter a bone of contention between China and Russia, until it finally went to Russia, bit by bit, between 1847 and 1881. The Kalmuks and Kazakhs played a special part in Russo-Chinese relations. The Chinese had sent a mission to the Kalmuks farthest west, by the lower Volga, and had entered into relations with them, as early as 1714. As Russian pressure on the Volga region continually grew, these Kalmuks (mainly the Turgut tribe), who had lived there since 1630, decided to return into Chinese territory (1771). During this enormously difficult migration, almost entirely through hostile territory, a large number of the Turgut perished; 85,000, however, reached the Hi region, where they were settled by the Chinese on the lands of the eastern Kalmuks, who had been largely exterminated.

“In the south, too, the Chinese came into direct touch with the European powers. In 1757 the English occupied Calcutta, and in 1766 the province of Bengal. In 1767 a Manchu general, Ming Jui, who had been victorious in the fighting for eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang), marched against Burma, which was made a dependency once more in 1769. And in 1790-1791 the Chinese conquered Nepal, south of Tibet, because Nepalese had made two attacks on Tibet. Thus English and Chinese political interests came here into contact.

“For the Qianlong period's many wars of conquest there seem to have been two main reasons. The first was the need for security. The Mongols had to be overthrown because otherwise the homeland of the Manchus was menaced; in order to make sure of the suppression of the eastern Mongols, the western Mongols (Kalmuks) had to be overthrown; to make them harmless, Turkestan and the Ili region had to be conquered; Tibet was needed for the security of Turkestan and Mongolia—and so on. Vast territories, however, were conquered in this process which were of no economic value, and most of which actually cost a great deal of money and brought nothing in. They were conquered simply for security. That advantage had been gained: an aggressor would have to cross great areas of unproductive territory, with difficult conditions for reinforcements, before he could actually reach China. In the second place, the Chinese may actually have noticed the efforts that were being made by the European powers, especially Russia and England, to divide Asia among themselves, and accordingly they made sure of their own good share.

Rebellions and Wars in Southern China During the Qing Dynasty

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), Imperial China expanded central-government control to Taiwan relatively easily, but Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, and the northwest continued to be problematic. In the southwest, there were wide-scale “Miao Rebellions," a generic term for all indigenous uprisings in the area. There were major rebellions in the 1670s, the 1680s, and again in the late 1730s. Qing records list some 350 uprisings in Guizhou between 1796 and 1911, and this number may be an undercount.No sooner had the state established firmer control over the minority peoples of the southwest then they faced the armed uprisings ofMuslim ethnic and religious movements in Shaanxi and Gansu (1862-1875), and the “Panthay" Muslim Rebellion in Yunnan (1856-1873), which had set up its capital in Dali. Even after the status of Xinjiang was changed from a military colony to a province in 1884, Muslim resistance continued until the end of the dynasty. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

In late Qing, the Han too were in rebellion: the Taiping Rebellion, which began among the Hakka in Guangxi and Guangdong, held most of southeast China during the 1850s and 1860s and extended its influence into Guizhou and Sichuan. The Nien Rebellion in the same period dominated in the area north of the Huai River.What seems to have kept the Qing in power throughout was a firm alliance of interest with the Han literati-elites who filled the bureaucratic posts of empire. In time, the Qing emperors out-Confucianized the Chinese themselves, adopting and encouraging traditional Chinese political and social thought based on the Confucian canon and assimilating to Chinese cultural styles. One might even say that they identified with the Han in viewing all other ethnic groups as “barbarians."

See Miao Rebellions in the 1700s and 1800s Under MIAO MINORITY: HISTORY, GROUPS, RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; LEADERS OF THE TAIPING REBELLION AND THE IDEOLOGY BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com

Russians Versus Qing Chinese in Turkestan (Xinjiang, Western China)

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The penetration of the Chinese into Turkestan (Xinjiang) took place just at the time when the Russians were enormously expanding their empire in Asia, and this formed the third problem for the Manchus. In 1650 the Russians had established a fort by the river Amur. The Manchus regarded the Amur (which they called the "River of the Black Dragon") as part of their own territory, and in 1685 they destroyed the Russian settlement. After this there were negotiations, which culminated in 1689 in the Treaty of Nerchinsk. This treaty was the first concluded by the Chinese state with a European power. Jesuit missionaries played a part in the negotiations as interpreters. Owing to the difficulties of translation the text of the treaty, in Chinese, Russian, and Manchurian, contained some obscurities, particularly in regard to the frontier line. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Accordingly, in 1727 the Russians asked for a revision of the old treaty. The Chinese emperor, whose rule name was Yongzheng, arranged for the negotiations to be carried on at the frontier, in the town of Kyakhta, in Mongolia, where after long discussions a new treaty was concluded. Under this treaty the Russians received permission to set up a legation and a commercial agency in Beijing, and also to maintain a church. This was the beginning of the foreign Capitulations. From the Chinese point of view there was nothing special in a facility of this sort. For some fifteen centuries all the "barbarians" who had to bring tribute had been given houses in the capital, where their envoys could wait until the emperor would receive them—usually on New Year's Day. The custom had sprung up at the reception of the Huns. Moreover, permission had always been given for envoys to be accompanied by a few merchants, who during the envoy's stay did a certain amount of business. Furthermore the time had been when the Uighurs were permitted to set up a temple of their own.

At the time of the permission given to the Russians to set up a "legation", a similar office was set up (in 1729) for "Uighur" peoples (meaning Muslims), again under the control of an office, called the Office for Regulation of Barbarians. The Muslim office was placed under two Muslim leaders who lived in Beijing. The Europeans, however, had quite different ideas about a "legation", and about the significance of permission to trade. They regarded this as the opening of diplomatic relations between states on terms of equality, and the carrying on of trade as a special privilege, a sort of Capitulation. This reciprocal misunderstanding produced in the nineteenth century a number of serious political conflicts. The Europeans charged the Chinese with breach of treaties, failure to meet their obligations, and other such things, while the Chinese considered that they had acted with perfect correctness.

Russians Versus Qing Chinese in Turkestan (Xinjiang) and Northern China

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The penetration of the Chinese into Turkestan (Xinjiang) took place just at the time when the Russians were enormously expanding their empire in Asia, and this formed the third problem for the Manchus. In 1650 the Russians had established a fort by the river Amur. The Manchus regarded the Amur (which they called the "River of the Black Dragon") as part of their own territory, and in 1685 they destroyed the Russian settlement. After this there were negotiations, which culminated in 1689 in the Treaty of Nerchinsk. This treaty was the first concluded by the Chinese state with a European power. Jesuit missionaries played a part in the negotiations as interpreters. Owing to the difficulties of translation the text of the treaty, in Chinese, Russian, and Manchurian, contained some obscurities, particularly in regard to the frontier line. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Accordingly, in 1727 the Russians asked for a revision of the old treaty. The Chinese emperor, whose rule name was Yongzheng, arranged for the negotiations to be carried on at the frontier, in the town of Kyakhta, in Mongolia, where after long discussions a new treaty was concluded. Under this treaty the Russians received permission to set up a legation and a commercial agency in Beijing, and also to maintain a church. This was the beginning of the foreign Capitulations. From the Chinese point of view there was nothing special in a facility of this sort. For some fifteen centuries all the "barbarians" who had to bring tribute had been given houses in the capital, where their envoys could wait until the emperor would receive them—usually on New Year's Day. The custom had sprung up at the reception of the Huns. Moreover, permission had always been given for envoys to be accompanied by a few merchants, who during the envoy's stay did a certain amount of business. Furthermore the time had been when the Uighurs were permitted to set up a temple of their own.

At the time of the permission given to the Russians to set up a "legation", a similar office was set up (in 1729) for "Uighur" peoples (meaning Muslims), again under the control of an office, called the Office for Regulation of Barbarians. The Muslim office was placed under two Muslim leaders who lived in Beijing. The Europeans, however, had quite different ideas about a "legation", and about the significance of permission to trade. They regarded this as the opening of diplomatic relations between states on terms of equality, and the carrying on of trade as a special privilege, a sort of Capitulation. This reciprocal misunderstanding produced in the nineteenth century a number of serious political conflicts. The Europeans charged the Chinese with breach of treaties, failure to meet their obligations, and other such things, while the Chinese considered that they had acted with perfect correctness.

Rebellions Against the Qing Dynasty

After the Ming Dynasty collapsed, the emperor and his court fled to southern China, where they hoped to regroup and drive the barbarian Manchus from the country. One of the most successful rebellions against the Manchus was led by a half-Japanese warrior pirate named Koxinga who had befriended a Ming prince. Koxinga commanded a fighting force of 8,000 war junks, 240,000 Ming warriors and 500,000 South China Sea pirates. His warriors — who reportedly had to lift a 600 pound stone lion before they were recruited — fought with iron masks and used long swords to maim cavalry horses. Although he failed to overthrow the Manchus, he was successful in driving the Dutch from Taiwan, and for this he is regarded as a national hero.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The period of Qianlong is not only that of the greatest expansion of the Chinese empire, but also that of the greatest prosperity under the Manchu regime. But there began at the same time to be signs of internal decline. If we are to fix a particular year for this, perhaps it should be the year 1774, in which came the first great popular rising, in the province of Shandong. In 1775 there came another popular rising, in Henan—that of the "Society of the White Lotus". This society, which had long existed as a secret organization and had played a part in the Ming epoch, had been reorganized by a man named Liu Song. Liu Song was captured and was condemned to penal servitude. His followers, however, regrouped themselves, particularly in the province of Anhui. These risings had been produced, as always, by excessive oppression of the people by the government or the governing class. As, however, the anger of the population was naturally directed also against the idle Manchus of the cities, who lived on their state pensions, did no work, and behaved as a ruling class, the government saw in these movements a nationalist spirit, and took drastic steps against them. The popular leaders now altered their program, and acclaimed a supposed descendant from the Ming dynasty as the future emperor. Government troops caught the leader of the "White Lotus" agitation, but he succeeded in escaping. In the regions through which the society had spread, there then began a sort of Inquisition, of exceptional ferocity. Six provinces were affected, and in and around the single city of Wuch'ang in four months more than 20,000 people were beheaded. The cost of the rising to the government ran into millions. In answer to this oppression, the popular leaders tightened their organization and marched north-west from the western provinces of which they had gained control. The rising was suppressed only by a very big military operation, and not until 1802. There had been very heavy fighting between 1793 and 1802—just when in Europe, in the French Revolution, another oppressed population won its freedom. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The Qianlong emperor abdicated on New Year's Day, 1795, after ruling for sixty years. He died in 1799. His successor was Jen Tsung (1796-1821; reign name: Chia-Qing). In the course of his reign the rising of the "White Lotus" was suppressed, but in 1813 there began a new rising, this time in North China—again that of a secret organization, the "Society of Heaven's Law". One of its leaders bribed some eunuchs, and penetrated with a group of followers into the palace; he threw himself upon the emperor, who was only saved through the intervention of his son. At the same time the rising spread in the provinces. Once more the government succeeded in suppressing it and capturing the leaders. But the memory of these risings was kept alive among the Chinese people. For the government failed to realize that the actual cause of the risings was the general impoverishment, and saw in them a nationalist movement, thus actually arousing a national consciousness, stronger than in the Ming epoch, among the middle and lower classes of the people, together with hatred of the Manchus. They were held responsible for every evil suffered, regardless of the fact that similar evils had existed earlier.

Mafia-like Chinese triads, which now rule much of the heroin trade out of east Asia and control organized crime in Hong Kong, descend from secret societies established to fight the Manchus.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Qing soldiers, Columbia University;

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021