TRADITIONAL CHINESE VIEW OF THE STATE

Emperor Qin

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The traditional Chinese state was a powerful force throughout Chinese history, with the king or emperor a central concern of individuals at every level of society. In many ways, the state was pictured as a larger version of the family. The king or emperor was, himself, the leader of a family, and owed his ruling position to the status of that clan and his position within it. From a very early date, the populace of China under the ruler’s control was referred to as “the hundred surnames” – picturing the ruler’s subjects in terms of their family identities. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“The earliest formal ideology of the Chinese state – a system of thought we now call “Confucianism” – began by making a very clear distinction between the unqualified obedience to one’s parents and one’s obligations towards a ruler. In the case of a ruler, one owed not unqualified obedience of filiality, but rather unqualified loyalty, which included an obligation to argue against bad policies and to refuse to act on immoral orders. But over the centuries, as the power of the imperial state grew, this distinction grew increasingly unclear to most people and most government officers. Early Confucianism had spoken of the ruler as “the father and mother of the people.” Originally, this had pointed to the ruler’s obligation to treat the people with as much care as he would treat his children, but in time it came equally to suggest that people owed to the ruler the same unquestioning obedience they owed to their fathers. /+/

“In practice the state’s attitude towards the people was much closer to a master-servant relationship than a family one, and enormous resources were devoted to providing the state with tools of social control that would ensure obedience. While China was far too large and communications far too undeveloped for the state to be truly “totalitarian,” in the modern sense, there was no belief that individuals had “rights” that the government could not violate without strong justification, and the basis for a true totalitarian period that China underwent in the 20th century was well laid in the structures and ideology of the traditional state. In a sense, the strong concept of the group and the relatively weak concept of the individual as a formally independent being that lay at the center of the Chinese family enabled the state to make claims on people almost as strong as those of the family. /+/

“By contrast, social forms that tend to be more closely tied to notions of “free association” – councils of elders, neighborhood groups, trade associations, guilds – these did not flourish in traditional China, except as the state sponsored their formation as government-mandated social control instruments. In Europe, organizations of this type were important in building an arena of civil society that individuals encountered outside the family and apart from state sponsorship. One of the problems often identified as an obstacle to the development of a fully modern, democratic China is the relative absence, even now, of a rich social culture of non-familial voluntary associations. /+/

Good Chinese History Websites: 1) Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia 4) China Knowledge; 5) Gutenberg.org e-book gutenberg.org/files ; Links in this Website: Main China Page factsanddetails.com/china (Click History);

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FIRSTS, ACHIEVEMENTS AND THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com; THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY: CIVILIZATION, FOREIGNERS AND THE DEFINITION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE HISTORICAL THEMES RELATED TO GEOGRAPHY, WEATHER AND THE ENVIRONMENT factsanddetails.com; SIMA QIAN AND THE HISTORY OF CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com; MEDIEVAL CHINESE WARFARE AND MILITARY TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com; SUN TZU AND THE ART OF WAR factsanddetails.com; FIRST HALF OF THE ART OF WAR: PLANS, STRATEGIES AND TACTICS factsanddetails.com; SECOND HALF OF THE ART OF WAR: PRACTICAL MATTERS AND SPIES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com ; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com ; "China: A History" by John Keay Amazon.com ; "Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Idea of Strong Chinese State

Historian Francis Fukuyama of Johns Hopkins wrote: “China was the first society in the world to recruit public officials not on the basis of their family connections, but because they passed a demanding examination. It governed a huge territory through a system of prefectures 1,800 years before France developed a comparable system and implemented a uniform system of weights and measures, It also developed a sophisticated literary culture by which current generations could learn from the past.”

Historian Francis Fukuyama of Johns Hopkins wrote: “China was the first society in the world to recruit public officials not on the basis of their family connections, but because they passed a demanding examination. It governed a huge territory through a system of prefectures 1,800 years before France developed a comparable system and implemented a uniform system of weights and measures, It also developed a sophisticated literary culture by which current generations could learn from the past.”

”As a result of the 500 years of intensive warfare that occurred during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period (the eastern Zhou dynasty, 711-211 B.C.),” Fukuyama wrote, “Chinese states formed and began ti consolidate into a smaller number of larger polities. As a result of the desperate need to mobilize resources for war, they developed bureaucratic administrations that relied increasingly on impersonal administration rather than patrimonial recruitment that was typical of earlier periods of Chinese history.”

Some have asserted that China’s rise debunks Fukuyama’s 1989 thesis that the fall of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc was “The End of History.” Some have gone as far as to say that China’s rise is ushering in a New Age of Authoritarianism in which Chinese authoritarianism will offer a model that developing countries will chose instead of liberal democracy.

Civilization State and Tributary System

"The Chinese do not think of themselves in terms of nation but civilization; it is the latter that gives them their sense of identity...The maxim of a nation state is "one nation, one system"; that of a civilization state is, of necessity, "one country, several systems."...Think back to the constitutional formula that underpinned the handover of Hong Kong : "one country, two systems." Despite Western skepticism, the Chinese really mean it, as the Hong Kong of today clearly illustrates."

Jacques also said that China can be viewed as it was in Imperial times as the center of a tributary state system, which organized inter-state relations in East Asia for thousands of years. Jacques wrote: "It was a loose and flexible system of states that was organized around the dominance of China, the acceptance of the latter's cultural superiority and a symbolic tribute that was paid in return for protection of the Chinese Emperor. That system lasted into about 1900."

"The deeply rooted attitudes that formed the tributary system have never really gone away, whether on the part of the Chinese or others. Furthermore, the conditions that swept it away"the decline of China and the arrival of European colonialism (and the subsequent influence of the United States) have disappeared....We are now witnessing the rapid reconfiguration of the region around a resurgent China. It is entirely plausible that we might once again see the return, in a modern context, of some element of the tributary state system, thereby challenging the global dominance of that European 1295 invention (the westphalian system of sovereign, independent states."

Traditional Political Culture in China

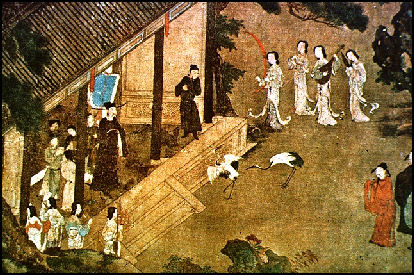

Ming era tribute Dr. Eno wrote: “The political culture of traditional China from the beginnings of the historical era until the beginnings of this century treated "social harmony" as the most desirable of all political outcomes. Values that the modern West has come to see as absolute requirements, such as the preservation of individual rights and the freedom to develop one’s unique talents to the fullest, were never clearly articulated in traditional China. In large part, this was a product of the mainstream Chinese concept of the individual that laid such great stress upon the organic links that bound each person to his or her family and community. When individuals are defined largely in terms of their roles in larger communities, it is more difficult to see why a strong concept of individual rights and freedom make sense, and much more difficult to see people as possessing natural responsibilities towards the larger community that shaped their identities and nurtured their well being. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Traditional China tended to conceive the goal of social harmony in terms of an ideal picture of the perfect society. Such an ideal society would be "homeostatic", which means that it would represent a self-regulating system. Should the harmony of this homeostatic system be unbalanced by natural or human disasters, the political institutions that structured it would be capable of responding automatically to restore harmony. The political ideals of most of the thinkers we will encounter in this course tend to reflect this traditional vision. (Note how different this is from our contemporary American excitement about the unpredictable nature of the future, and our willingness to undertake social experiments. In the course of human history, to the degree these represent our present attitudes, our society is an unusual exception.) /+/

“For most people in traditional China, the ideal homeostatic society was structured according to the principle of a complex hierarchy of social roles, culminating in a single powerful ruler — a king or emperor — at the apex. This was not just a theoretical model; this was the shape of Chinese politics from before 1000 B.C. on. China is the home of bureaucracy. Complex structures of court and regional appointments may be discovered in the earliest written records of China, and one of the outcomes of the political debates of the Classical period was the invention of the civil service examination system in China shortly thereafter. Moreover, the concept of a single, Heaven-mandated ruler did not flag in China until the end of the 19th century — some people would say until the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. /+/

“Traditionally, the Chinese pictured their past and future in terms of a succession of kings. There was no calendar of consecutive years in China until 1949; instead, years were numbered according to the reigns of kings, and the sequence began anew with the accession of each new ruler. Moreover, the past was always described in terms of long eras marked by continuous dynasties of rulers, who handed the throne from father to son for generations. Even as early as the Classical period this was so. Our thinkers spoke of themselves as living in the period of the Zhou Dynasty, and described the past in terms of the preceding Shang Dynasty, and before that the Xia Dynasty. Only when thinking beyond the long distant beginnings of the Xia did Classical people describe the past differently. And still, though this primitive past included no dynasties, it was still marked as a succession of kings, legendary figures whom Classical folklore had borrowed from the realm of myth and recreated as the 10 imaginary cultural creators and first rulers of China. (We will discuss pre-philosophical history in a subsequent section.)

Lack of Rule of Law in China

”But while China was precocious in developing a modern state...and was far more advanced in state administration than the contemporaneous Roman Republic, Fukuyama wrote: “it lacked other critical political developments, rule of law and accountable government. Rule of Law means that there is a body of law that is superior to the current ruler, which constrains the ruler’s decision making. This never existed in China the way it did in ancient Israel, Greece, Rome or India, in part because Chinese law was never grounded n religion. Rather the law was whatever the emperor said it was, and there was no institutional body in China that could over come his decrees.”

”The consequence of a lack f rule of law was that China could experience extreme forms of tyranny. The first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, uprooted thousands of aristocratic families, confiscated their property, instituted extremely harsh punishments and reportedly buried alive 400 Confucian scholars, as well as burning their books.”

”Accountable government, or what we call democracy, developed around the world at a much later time tham either the state or rule of law. Accountability does not necessarily depend on popular elections. Rulers can be educated to have a sense of moral responsibility to the people they govern, in the absence of procedural checks on their power. This existed in China, and was in many ways the essence of Confucian ideology. But procedural accountability, by which either elites or ordinary citizens can constrain rulers, never existed in China. The historical reason for his in my view was the fact that from an early date, there were never strong institutionalized actors apart from the state, like a landed aristocracy, independent commercial cities, or a well-organized peasantry, that would have formed a counterweight to the state.”

Strong State and Lack of Rule of Law

punishment in 1875

”China’s contemporary institutional legacy is thus a strong, centralized state and relatively good government. In the best of times, the Chinese state feels morally constrained to do the right things for its population in a way that is hard to replicate in other parts of the world. Thus virtually all the worlds— successful authoritarian modernizers, including South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam and modern China, itself, are all located in East Asia and have historically been under Chinese cultural influence. They have compiled impressive economic and social development records when compared to comparable governments in Latin American, Africa or the Middle East. But Chinese tradition has not included rule of law or democracy and as a result, there are no institutional checks to prevent Chinese government from descending into despotism, as occurred during the Maoist period.”

”Unaccountable Chinese-style architecture comes at a price. In traditional China, common people were subject t all sorts of injustices perpetrated by landlords, corrupt local officials, bandits and the like. When their land was taken by a corrupt official, they had no recourse other than to protest to the emperor, The emperor wanted his realm to well governed and would try to discipline corrupt or arbitrary officials. But unless the people petitioning him were powerful r had some means of access to the palace, they had little chance of achieving justice...In many ways things are not all that different in contemporary China.”

”A lack of constraint by either law or elections means accountability flows only in one direction, upwards towards the Communist Party and central government and not downwards toward the people. There is a whole range of problems in contemporary China regarding issues like corruption, environmental damage, property rights and the like that cannot be properly resolved by the existing political system.”

Early Chinese Political Philosophers

Tsinghua University professor Yan Xuetong wrote in the New York Times: "Ancient Chinese political theorists like Guanzi, Confucius, Xunzi and Mencius were writing in the pre-Qin period, before China was unified as an empire more than 2,000 years ago " a world in which small countries were competing ruthlessly for territorial advantage. [Source: Yan Xuetong, New York Times, November 20, 2011. Yan Xuetong, the author of "Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power," is a professor of political science and dean of the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua University.]

It was perhaps the greatest period for Chinese thought, and several schools competed for ideological supremacy and political influence. They converged on one crucial insight: The key to international influence was political power, and the central attribute of political power was morally informed leadership. Rulers who acted in accordance with moral norms whenever possible tended to win the race for leadership over the long term.

China was unified by the ruthless king of Qin in 221 B.C., but his short-lived rule was not nearly as successful as that of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty, who drew on a mixture of legalistic realism and Confucian 'soft power' to rule the country for over 50 years, from 140 B.C. until 86 B.C.

According to the ancient Chinese philosopher Xunzi, there were three types of leadership: humane authority, hegemony and tyranny. Humane authority won the hearts and minds of the people at home and abroad. Tyranny — based on military force — inevitably created enemies. Hegemonic powers lay in between: they did not cheat the people at home or cheat allies abroad. But they were frequently indifferent to moral concerns and often used violence against non-allies. The philosophers generally agreed that humane authority would win in any competition with hegemony or tyranny.

Confucianism and Government

Confucius as an administrator

Confucianism originated and developed as the ideology of professional administrators and continued to bear the impress of its origins. Imperial-era Confucianists concentrated on this world and had an agnostic attitude toward the supernatural. They approved of ritual and ceremony, but primarily for their supposed educational and psychological effects on those participating. Confucianists tended to regard religious specialists (who historically were often rivals for authority or imperial favor) as either misguided or intent on squeezing money from the credulous masses. The major metaphysical element in Confucian thought was the belief in an impersonal ultimate natural order that included the social order. Confucianists asserted that they understood the inherent pattern for social and political organization and therefore had the authority to run society and the state. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Confucianists claimed authority based on their knowledge, which came from direct mastery of a set of books. These books, the Confucian Classics, were thought to contain the distilled wisdom of the past and to apply to all human beings everywhere at all times. The mastery of the Classics was the highest form of education and the best possible qualification for holding public office. The way to achieve the ideal society was to teach the entire people as much of the content of the Classics as possible. It was assumed that everyone was educable and that everyone needed educating. The social order may have been natural, but it was not assumed to be instinctive. Confucianism put great stress on learning, study, and all aspects of socialization. Confucianists preferred internalized moral guidance to the external force of law, which they regarded as a punitive force applied to those unable to learn morality. *

Confucianists saw the ideal society as a hierarchy, in which everyone knew his or her proper place and duties. The existence of a ruler and of a state were taken for granted, but Confucianists held that rulers had to demonstrate their fitness to rule by their "merit." The essential point was that heredity was an insufficient qualification for legitimate authority. As practical administrators, Confucianists came to terms with hereditary kings and emperors but insisted on their right to educate rulers in the principles of Confucian thought. Traditional Chinese thought thus combined an ideally rigid and hierarchical social order with an appreciation for education, individual achievement, and mobility within the rigid structure. *

While ideally everyone would benefit from direct study of the Classics, this was not a realistic goal in a society composed largely of illiterate peasants. But Confucianists had a keen appreciation for the influence of social models and for the socializing and teaching functions of public rituals and ceremonies. The common people were thought to be influenced by the examples of their rulers and officials, as well as by public events. Vehicles of cultural transmission, such as folk songs, popular drama, and literature and the arts, were the objects of government and scholarly attention. Many scholars, even if they did not hold public office, put a great deal of effort into popularizing Confucian values by lecturing on morality, publicly praising local examples of proper conduct, and "reforming" local customs, such as bawdy harvest festivals. In this manner, over hundreds of years, the values of Confucianism were diffused across China and into scattered peasant villages and rural culture. *

See Separate Article CONFUCIANISM, GOVERNMENT AND EDUCATION factsanddetails.com

Legalism

The School of Law (fa), or Legalism was an unsentimental and authoritarian doctrine formulated by Han Fei Zi (d. 233 B.C.) and Li Si (d. 208 B.C.), who maintained that human nature was incorrigibly selfish and therefore the only way to preserve the social order was to impose discipline from above and to enforce laws strictly. The Legalists exalted the state and sought its prosperity and martial prowess above the welfare of the common people. Legalism became the philosophic basis for the imperial form of government. When the most practical and useful aspects of Confucianism and Legalism were synthesized in the Han period (206 B.C. - A.D. 220), a system of governance came into existence that was to survive largely intact until the late nineteenth century. Legalism was diametrically opposed to Mencius. Xun Zi (ca. 300-237 B.C.), a Confucian follower that influenced the Legalists, preached that man is innately selfish and evil and that goodness is attainable only through education and conduct befitting one's status. He also argued that the best government is one based on authoritarian control, not ethical or moral persuasion. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Legalism is a network of ideas concerning the art of statecraft. It looks at the problems of the Warring States period entirely from the perspective of rulers (although the authors of Legalist texts were not themselves rulers, but rather men who wished to be employed by rulers as their counselors and ministers). Legalism provides answers to the question, how can a ruler effectively organize and control his government so as to yield the greatest possible increase in state wealth and territory. Legalist arguments assume that these goods are only meaningful when they are under the absolute control of an autocrat, that is, a ruler whose personal power within his realm is absolute and unconstrained. If among all the ideologies of personal and political governance that flourished in contention during the Warring States period there was a winner, it was Legalism. Legalism was principally the development of the ideas that lay behind Shang Yang’s reforms, and these reforms were what led most materially to Qin’s ultimate conquest over the other states of Eastern Zhou China in 221 B.C. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

See Separate Article LEGALISM factsanddetails.com ; SHANG YANG AND LI SHI: THE IMPLEMENTORS OF LEGALISM factsanddetails.com ; HAN FEIZI: THE VOICE OF THE LEGALISTS factsanddetails.com

Legalism Versus Confucianism

Li Si, a proponent of Legalism

David K. Schneider wrote in The National Interest: “Legalism has for centuries been the center of gravity of Chinese political culture. Even Confucianism, commonly believed to be China’s ruling ethos, was first articulated in the sixth through third centuries B.C. in opposition to the practice of establishing legal codes. The earliest of these were inscribed on bronze vessels in the sixth century B.C. in the states of Zheng and Jin. Confucius’s (551–479 B.C.) classic argument against this use of law as a tool of statecraft is recorded in the Analects: “When you govern them by means of administration and punishments, the people evade these measures and are without shame. When you govern them by means of virtue and ritual, they have shame and reform themselves.” [Source: David K. Schneider, The National Interest, April 20, 2016. David K. Schneider is associate professor of Chinese at University of Massachusetts Amherst, author of Confucian Prophet: Political Thought in Du Fu’s Poetry (752–57) (Cambria Press, 2012), and a Wikistrat senior analyst. His present research is on war and diplomacy in Chinese political thought and culture]

“Confucius advocates royal power based in morality and tradition. Moral education and self-cultivation would bring a restoration of the good society. These ideas are framed in direct opposition to the Legalist measures of bureaucratic administration and punishment, the political instruments most favored by the rulers of Confucius’s time. The Legalist answer to this argument is powerful. Han Fei (280–33 B.C.), one of Legalism’s foremost voices, posed the example of a recalcitrant boy. All the admonitions toward goodness by his parents, neighbors and teachers fail. But, once the district magistrate sends soldiers to enforce the law, he is brought by the sheer force of terror to reform his conduct. What all the moral suasion of a loving family and tradition could not achieve, the bureaucratic state brings about at a stroke.

“The vigorous debate between advocates of legal codes and followers of Confucius brought forth both the Confucian and Legalist schools of philosophy during the Warring States period (475–221 B.C.). Legalist thought received a full philosophical articulation in the writings of statesmen such as Shang Yang (fourth century B.C.) and Han Fei, both associated with the state of Qin, which succeeded in the military conquest of all the Warring States and the founding of the first Chinese empire in 221 B.C.. It was Legalist thought and practice that propelled the centralization of power in the hands of a single monarch, laid the foundations for the state bureaucracy and established the efficient and effective legal codes that became the pattern for Chinese politics for the next two millennia.

“No subsequent dynasty ever dismantled the Qin bureaucratic-Legalist state. In the second century B.C., Legalist methods were used by the succeeding Han dynasty Emperor Wu to consolidate the power and authority of the Han government, which lasted from the third century B.C. to the third century AD. The Tang dynasty (618–907) implemented Legalist ideas again in the early seventh century with the promulgation of the Great Tang Legal Code, which served as the foundation of Chinese law through the rest of its dynastic history, into the twentieth century. Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the Ming dynasty (1368–644), and known to posterity as Ming Taizu, left detailed instructions to his successors that attempted to make permanent for all time his code of laws and regulations. He also famously abolished the office of the prime minister in a move to concentrate all power in the hands of the emperor himself and a secretariat that worked closely with him, a reenactment of the centralization of the Qin state and an anticipation of Xi Jinping’s successful accumulation of political and military authority with the establishment of the National Security Committee.

Ancient Chinese History Based on Moral Messages Rather Than Historical Facts?

In the 1970s, a sinologist named J. I. Crump convincingly argued that the classical historical texts "Zhanguo ce" was not written as a historical record. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ Rather, it was a collection of imaginative accounts, some based on historical fact, others pure fiction, that were intended not for students of history but for students of rhetoric. The text was an exercise book for young men aspiring to status and wealth through rhetorical skills. Crump’s hypothesis undermined our confidence in our sources for Warring States history, by suggesting how presentation of “facts” and persuasion were linked in the classical narrative, but it also opened a window to understanding the “professional” profile of rhetorical arts in early China (resembling, in some ways, the role played by Sophism in Greece during the same age). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Upon examination, sections of certain other Warring States texts that seem to preserve historical facts turn out instead to be storehouses of conventional anecdotes explicitly presented as literary tropes useful in persuasions. One very influential text, the Legalist work "Han Feizi", includes many chapters which are collections of anecdotes ordered under headers which mark appropriate issues in convincing a ruler to adopt a Legalist point of view. /+/

“For example, in one of these chapters, “The Seven Tactics,” an introductory section lists very tersely seven precepts which a ruler ought to adopt in administration, according to the tenets of Legalism. The first of these is, “Comparing and inspecting different points of view.” Each of the tactics is then explained in more detail somewhat further on. In the case of the first, we read, “If the ruler does not compare things he sees and hears he will never get at the truth. If what he hears all derives from one particular conduit, he will be deceived by his ministers.” Then there follow a list of evidentiary sources, beginning, “This rule is proved by the dwarf’s dream of the cooking stove.” The main body of the chapter consists of a long series of anecdotes. The first runs like this:Mi Zixia was a favorite of Duke Ling of Wei, who entrusted to him the administration of all public affairs. One day, the Duke’s dwarf jester said, “Your humble servant’s dream has come true!”“What did you dream?” asked the Duke. /+/

““Your servant dreamed of your majesty, but saw a cooking stove.”“What!” shouted the Duke. “I have always heard that anyone who dreams of a ruler sees the sun. Why would you have seen me as a cooking stove?”“Indeed,” replied the dwarf, “the sun shines upon everything under Heaven. Nothing can obscure it. And a ruler reigns over everyone in the state and nothing can delude him. This is why it is so that one who dreams of a ruler dreams he sees the sun. The light from a cooking stove, on the other hand, can be obscured if someone stands in front of it. Now, let us say that there were someone standing in front of your majesty. Would it not be possible for your servant to dream of your majesty as a cooking stove?” /+/

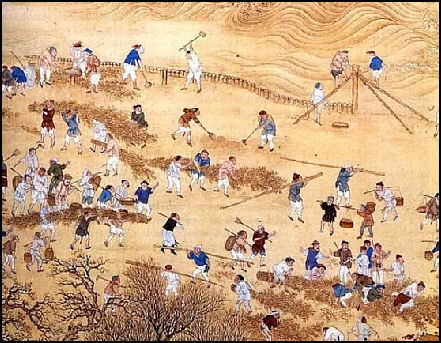

Making dikes on the Yellow River

"Clearly, the tale itself is fiction, though in this case, some of the background facts are correct. The point of the tale is to provide the Legalist courtier with ammunition for convincing a ruler of the wisdom of the Legalist dictum that no ruler should allow too much power to devolve to any one minister. The text is an “insider’s” handbook – if you’re looking for just the right rhetorical trick to engage a ruler and convince of your wisdom, it seems to say, just try one of these. The history of the Classical period has been “constructed” from thousands of anecdotes such as this one, preserved as tools of rhetoric in the texts of the various intellectual factions. It seems near impossible to determine how much of our detailed knowledge of” ancient China “is based on facts and how much on the collective imagination of courtiers whose speech-making anecdotes are actually the beginning of fiction in China. /+/

“Nevertheless, it would be correct to say that this ongoing process of recreating the past as didactic fiction was a means by which the literate class of "shi" created its own view of the Eastern Zhou era.What actually “happened,” even in the very recent past, may have had less impact on the times than the way in which character and event were re-embroidered into string after string of moral and political lessons. In some ways, the characters of this world of anecdotes – even the ones who never lived – may have had more influence on the Classical elite than the men and women as they really were.” /+/

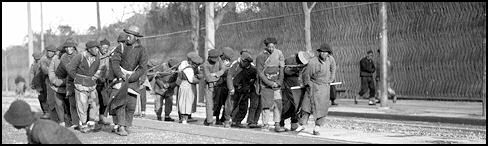

Authoritarian Rule and Labor in China

Huge labor forces of commoners were mobilized to build grand projects like the Grand Canal and the Great Wall of China. Intense labor also produced elaborate crafts that took generations to complete.

The iron-fisted authoritarian rule of the Communist Party is nothing new. China has a long history of authoritarian rule which goes back to its inception 4,000 years ago. In the imperial era, Chinese society was rigidly stratified with the emperor and the scholar class at the top and a child-like general population expected to follow orders of their paternal leaders. There is a widespread belief that emperors and leaders were great if they moved the country forward even if many people suffered. Under these conditions it is surprising that China has endured for as long a sit has.

Many historians believe the pattern of Chinese-style authoritarian rule was established by China's first great leader, Emperor Qin. Journalist Sheryl Wudunn wrote in the New York Times magazine, "Partly because the Qin emperor was so harsh his dynasty lasted just a few years after his death. Yet the Qin emperor laid a foundation that served China well. The next dynasty was the Han, which lasted more than four centuries and was a golden era—a flourishing age for the arts and scholarship as well as for the economy."

"Mao Zedong," wrote Wudunn, "acknowledged (and was flattered by) the similarities in vision and ruthlessness between him and the Qin emperor.” Both Qin and the Communists killed hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Chinese with their brutality and incompetence but they “also united China, redistributed land wealth and destroyed the special interests that were stifling economic growth” and paved the way for China to attain superpower status.

Human-powered street rollers in the 1920s

Ancient Roots of Chinese Liberalism

Liu Junning, an independent scholar in Beijing, wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “What we now call Western-style liberalism has featured in China's own culture for millennia. We first see it with philosopher Laozi, the founder of Taoism, in the sixth century B.C. Laozi articulated a political philosophy that has come to be known as wuwei, or inaction. "Rule a big country as you would fry a small fish," he said. That is, don't stir too much. "The more prohibitions there are, the poorer the people become," he wrote in his magnum opus, the "Daodejing." [Source: Liu Junning, Wall Street Journal, July 6, 2011]

For Mencius, a fourth-century B.C. philosopher and the most famous student of Confucius, a kingdom would be able to defend itself from outside attack if the king "runs a government benevolent to the people, sparing of punishments and fines, reducing taxes and levies. . . ." When asked by the King of Hui, "What virtue must there be to win the unification of the world”" Mencius replied, "It is the protection of the people." [Ibid]

Much later we find the writings of Huang Zongxi (1610-1695), known as "The Father of Chinese Enlightenment." A fierce critic of despotism and the divine rights of sovereigns, Huang once rhetorically asked, "Is it that the heaven and the earth with all their magnitude are destined only in favor of one person or one family among all the people?" His "Waiting for the Dawn: A Plan for the Prince," it should be noted, was written more than 50 years before John Locke's "Two Treatises of Government."

These are only a few of the many Chinese thinkers and intellectuals who over the centuries have investigated the nature of political power and the obligations owed by a ruler to a country's citizens. Note that Laozi and other classical thinkers also drew a connection between good, limited government in general and prosperity in particular.

To say that the narrative of liberty vs. power is uniquely "Western" is to turn a blind eye to the struggles of those who have gone before us. Individual rights are not a Western development any more than paper and gunpowder are inventions that are uniquely Chinese. Is Marxism "German"? Is Buddhism "Indian"? Of course not. When ideas are born, they take flight into the world to be used, improved or discarded by all of humanity. Constraints on political power and the protection of individual rights belong to all.

Imperial banners

Religion and History in China

Ancient Chinese agrarian religion revolved around the worship of natural forces and spirits who controlled the elements and presided over rivers, fields and mountains. Shaman known as wu acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds and performed rites to insure good weather and harvests and keep evil spirits at bay.

Even though China is regarded officially as an atheist state today, it has had an officially recognized religion since 2356 B.C., when science, religion, mythology and government were all linked together. Taoism and Confucianism began to take shape around the 5th and 6th centuries B.C. but evolved from religions that had been around in China for at least a thousand years before that.

The four centuries after the Han dynasty (3rd to 7th centuries A.D.) were characterized by disunity and chaos, which in turn lead to a receptivity to new religious ideas. This was the beginning of the Age of Faith, when Taoism flourished, Confucianism became a philosophy of the wealthy, and Buddhism took root. In the Age of Faith, Taoists and Buddhists fought over souls for salvation. Many Buddhist converts were formerly Taoists.

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “For the most part, China's emperors had not bothered much with religions. Buddhism had become very popular at a time of upheaval in the 6th Century, but it appealed mostly to people at the bottom of society. Christianity was one of the novelties which had come in with the colonial powers. They used gunboats to open China to trade, and shattered the image of order and invincibility cultivated by the Qing emperors. Vernacular translations of the Bible helped loosen the grip of the Confucian elites. [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, September 17, 2012]

Mandate of Heaven

Early Chinese monarchs were both priests and kings. The Chinese people believed that their rulers were chosen to lead with a "mandate of heaven" — the Chinese belief that a dynasty was ordained to rule, based on its demonstrated ability to do so. It was a kind of political legitimacy based on the notion that the overthrow of ruler was justified if the ruler became wicked, lost the trust of the people or double-crossed the supreme being.

The “mandate of heaven” was first adopted during the Zhou Dynasty (1100-221 B.C.) and was described as a divine right to rule. The philosopher Mencius (372-289 B.C.) wrote about it at length and framed it in both moral and cosmic terms, stating that if a ruler was just and carried out the prescribed rituals to the ancestors then his rule and the cosmic, natural and human order would be maintained.

Later the mandate idea was incorporated into the Taoist concept that the collapse of a dynasty was preceded by "Disapprovals of heaven," natural disasters such as great earthquakes, floods or fires and these were often preceded by certain cosmic signs. According to these beliefs on September 8, 2040 five planets will gather within the space of fewer than degrees "signaling the conferral of heaven's mandate."

The legendary emperors did not need to govern at all because the moral certitude that emanated from them was enough to bring about peace and prosperity. One ruler is said to have done nothing but reverently face the south.

See Separate Article MANDATE OF HEAVEN AND TIANXIA factsanddetails.com

Taiping Rebellion battle in 1854

Peasant Rebellions in China

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “Chinese history can be read as a series of peasant rebellions” and “for every Chinese rebellion which succeeds, there are scores which fail. Rebellions brought an end to the Qin dynasty in the Third Century B.C., the Mongol Yuan dynasty in the 14th Century, and nearly brought down the mighty Han dynasty, points out Beijing commentator Kaiser Kuo. Peasants are "passive actors" throughout most of history, he says, but occasionally they rise up to keep the dynasty in line. As in these earlier rebellions, many of those who joined Hong's Heavenly Army in the Taiping Rebellion (described a little bit below) had nothing to lose. Population growth had deprived them of a stake in society.”

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “Rebellions are indeed of constant occurrencebut the wonder is that they are not far more numerous. Things must have come to a desperate pass when the mass of the Chinese population deliberately defy the government. Even in cases of local disturbance, when there appears to the Chinese to be no safety except such as may be got by the protection of earthen walls thrown up around villages. The instinct of self-preservation does of course lead to efforts to put. down every rebellion, and in the end these efforts always succeed. But in the meantime, for long periods before the dilatory, movements of the officials, even bring relief in sight, the poor people suffer many miseries. And it not infrequently happens that the oppression of those sent to put down the uprising is an evil so much greater than the -rebellion, that the poor people are driven in self-defence to join the rebels. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“That local anarchy of the worst type may coexist with a government which is so strong as to be perfectly able to put down rebellions when its strength is brought to bear, is one of the strange phenomena of the Chinese Empire. Without specifying details, it must suffice to mention the significant existence in such widely sundered provinces as Shanxi, Sichuan and Shandong, of great numbers of mountain fortresses, into which the people make a practice of retreating as soon as a period of lawlessness sets in, abandoning all that is not moveable to the bands of pillagers, In some regions these forts on the tops of almost inaccessible mountains are the most conspicuous objects in the landscape, and in some of these enclosures, we have been assured, terrible massacres have taken place within the past quarter of a century. The people have learned ages ago that if it is desirable to avoid extermination, it can only be accomplished by doing for themselves as well as they can what the government ought to do for them.

Taoist Uprisings and the Taiping Rebellion

Taoism has been associated with a number of rebellions. Some of these were linked to political insurrections such as the Yellow Turban Rebellion of the A.D. 2nd century and Taping Rebellion of the 19th century. The fall of the first Sung dynasty was precipitated by a rebellion of Taoists responding to a crackdown on some of their esoteric rituals.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion occurred at a time when there was a great deal of discontent and economic hardship. The movement was led by one Chang Chio, who encouraged his followers to wear yellow robes and yellow turbans and told them if the current government was overthrown the present “Blue Heaven” period would be replaced by a “Yellow Heaven” period beginning in A.D. 184.

Yellow Turban followers were given a kind of baptism in which they confessed their sins and consumed a drink of water blessed with ashes from a charm, after which they were told they were protected from any kind of harm. Provided with information from a traitor, the movement was brutally put down by the government in A.D. 183, Chang Chio died before 184 but the rebellion carried on for another 20 years.

The Taiping rebellion was the world's bloodiest civil war. Lasting for 13 years from 1851 to 1864, it nearly toppled the Qing Dynasty and resulted in the death of 10 million to 20 million people — more than the entire population of England at that time. The conflict began as an uprising and a rebellion but became ‘simply a descent into anarchy.” It is also viewed by many historians as a precursor to the Long March and the Cultural Revolution. According to the BBC It taught the Communists lessons a century later, and is one reason why China's leaders keep a close eye on rural unrest today. [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, September 17, 2012 /]

The leader of Taiping Rebellion was Hong Xiuquan, who thought he was Christ's brother. "When people of this earth keep nothing for their private use, but give all things to God for all to use in common, then every place shall have equal shares, and everyone be clothed and fed," Hong declared. In many ways, he says, it was a message that was mirrored by another creed to arrive in China from outside a century later - Marxism. Mao took Marxism and bolted it on to this ancient yearning of China's farmers for land and justice. /

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In the 1840s a young man from Guangdong named Hong Xiuquan (1813-1864) created his own version of Christianity and made converts in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. Hong believed that he was the Younger Brother of Jesus and that his mission, and that of his followers, was to cleanse China of the Manchus and others who stood in their way and “return” the Chinese people to the worship of the Biblical God. Led by Hong, the “Godworshippers” in rural Guangxi rose in rebellion in 1856 in hopes of creating a new “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace” (Taiping Tianguo). Their movement is known in English as the Taiping movement (“taiping” meaning “great peace” in Chinese). The rebels swept through southern China and up to the Yangzi River, and then down the Yangzi to Nanjing, where they made their capital. Attempts to take northern China were unsuccessful, and the Taiping were eventually crushed in 1864. By that time, the Taiping Rebellion had caused devastation ranging over sixteen provinces with tremendous loss of life and the destruction of more than 600 cities. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

See Separate Article TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University/+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021