SIMA QIAN

Sima Qian

Sima Qian is regarded as China's 'grand historian'. Born between 145 and 135 B.C. to a family of court astrologers and the son of Sima Tan, the prefect of grand scribes to Emperor Wu of Han, Sima Qian becomes grand historian three years after his father's death in 110 B.C. He created an advanced form of calendar in 104 B.C.. In 99 B.C. he offended the emperor and chose castration as his punishment. "Among defilements, none is so great as castration. Any man who continues to live having suffered such a punishment is accounted as a nothing," Sima wrote. He later became a palace eunuch His “The Records of the Grand Historian” cover a period of 2,500 years [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 7, 2012 /*]

Much of what we know about China before the first century B.C. is what Sima described. Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “In a nation obsessed by its history, Sima Qian was the first and some say the greatest historian. In today's China, Sima Qian's book, The Records of the Grand Historian, is regarded as the grandest history of them all. What Herodotus is to Europeans, so Sima Qian is to Chinese.” /*\

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “In the study of early China we owe the greatest debt to Sima Qian, the Grand Historian of the court of Wu-di.” It is important “to acknowledge the contribution that Sima Qian has made to all later understanding of ancient China. The scale of his text (which runs over 3000 pages in modern commentary editions) and its pervasive sensitivity, intelligence, and sense of value are unmatched anywhere in the ancient world. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Our vision of ancient China has been overwhelmingly shaped by the perspective of this one man. We know that Sima Qian’s failings as a historian, many of which he was the first to admit, have led later historians into many important errors, and surely continue to blind us to certain aspects of ancient China. However, most of us who work in the field of early China believe that Sima Qian’s intellectual honesty and devotion to distinguishing between truth and fantasy as best he could make his history, the “Shiji”, an invaluable gift to us. In some ways, Sima Qian’s own tragic relationship to Wu-di serves as a symbol for the greatness and failure of the Chinese imperial system. For all these reasons, we will close this course with the reign of Wu-di, and later close these readings with an account of Sima Qian himself.”

Ban Gu (Pan Ku, A.D. 32–92) wrote Qian Hanshu (Ch'ienHan shu; History of the Han Dynasty), a continuation of Sima Qian's work.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FIRSTS, ACHIEVEMENTS AND THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com; THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY: CIVILIZATION, FOREIGNERS AND THE DEFINITION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE HISTORICAL THEMES RELATED TO GEOGRAPHY, WEATHER AND THE ENVIRONMENT factsanddetails.com; CHINESE HISTORY, RELIGION AND POLITICS: MANDATE OF HEAVEN AND VIEWS OF THE STATE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE DYNASTIES AND RULERS factsanddetails.com FAMILY AND GENDER IN TRADITIONAL CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The First Emperor: Selections from the Historical Records (Oxford World's Classics) by Sima Qian, Raymond Dawson Amazon.com ; “Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty I” by Qian Sima and Burton Watson Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com; “Life in Ancient China (Peoples of the Ancient World)” by Paul Challen Amazon.com ; “DK Eyewitness Books: Ancient China:” by Arthur Cotterell and Laura Buller Amazon.com; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com

Sima Qian’s Life

Another rending of Sima Qian long after he was dead

Dr. Eno wrote: “Sima Qian was the son of the Han court historian and inherited the position of his father, Sima Tan. The office of historian was not at that time confined to issues that we now think of as historical. The historian was principally an archivist and an astrologer. In an age when the rhythms of the heavens and of the earth were considered to bear so closely on the conduct of government, the position of court astrologer was an important one, and prior to Sima Tan it is likely that “historians” had paid little attention to organizing the records of the past.” /+/ [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University/+/ ]

“Sima Qian was born about 145 B.C. His father, whose basic ideas and values were reported by his son in an autobiographical afterword to the “Shiji”, was inclined towards the values of the Daoists. But he was an intelligent and eclectic man, and he had his son study widely. Among the teachers to whom he sent Sima Qian was Dong Zhongshu, who would have been at the height of his influence at that time. “While we tend to associate Dong first with his influence on Wu-di’s personnel policies and second with his yin-yang omenology, in his own time he was chiefly celebrated as a master of the “Spring and Autumn Annals”. One of the features of early Han “Annals” scholarship was the belief that Confucius had chosen to edit the “Annals” and implant his wisdom therein because he felt that “to discuss the Dao through empty theory would not be so effective as to illustrate its workings through action and event.” We may assume that Sima Qian was thoroughly instructed in this notion, and it makes sense to see the “Shiji” as displaying his portrait of the eternal Dao through the coloration he gives to his account of the changing past. /+/

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see 4.12 SIMA QIAN AND OUR VIEW OF EARLY CHINA by Robert Eno scholarworks.iu.edu

Sima Qian and His Father’s Mission to Record the History of the World (China)

Sima Qian’s father Sima Tan appears to have been the one who first conceived of the project of writing a history of the world (which is to say, China). In his account of his father’s death, Sima Qian wrote: “Our ancestors were grand historians for the house of Zhou. From the most ancient times they were eminent and renowned when in the days of Yu and the Xia they were in charge of astronomical affairs.In later ages our family declined. Will this tradition end with me? If you in turn become grand historian, you must continue the work of your ancestors. [Source: “Shiji” 130.3295 -]

“You must not forget what I have desired to express through my writing. Filiality begins with the serving of your parents; next you must serve your sovereign; finally, you must make something of yourself so that your name may go down through the ages to the glory of your father and mother. This is the most important aspect of filiality. -

“Now the various feudal states have merged into one and the records of the old chronicles and records have become scattered and lost. The house of Han has arisen and all the world is united under one rule. I have been grand historian, and yet I have failed to make a record of all the enlightened rulers and wise lords, the faithful ministers and gentlemen who were prepared to die for what was right. I am fearful that the historical materials will be neglected and lost. You must remember and think of this!” -

Sima Qian records his own tearful response, in which he pledged that he would do as his father wished. From the time that Sima Tan died in 110 until his own death about the year 90 B.C., Sima Qian devoted himself whole-heartedly to the recovery of ancient records, their organization and verification, and the writing of the “Shiji”. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Sima Qian’s Castration

Wu Di

Dr. Eno wrote: “In 98, the incident that became the turning point of Sima Qian’s career occurred. A general named Li Ling, who was pursuing Wu-di’s campaigns against the Xiongnu, was ambushed by a far superior force. Facing certain defeat, he chose to surrender, thus, in Wu-di’s eyes, violating the code of conduct of a Han military leader. Li Ling was associated with certain factions at court, and their enemies seized the occasion of his failure to excoriate him in the hope of discrediting others. When Sima Qian, who was apparently connected with neither faction, sent a memo courageously supporting Li Ling, the emperor was led to understand that the historian was acting as the dupe of a party anxious to undermine Wu-di’s authority. Consequently, he ordered that Sima Qian be sentenced to castration. /+/

“This arbitrary and brutal response to what he himself regarded as a courageous memorial loyal to the interests of the throne threw Sima Qian into dismay. There existed two possible alternatives to undergoing the punishment of castration, which was the most shameful of all punishments short of execution. The first was to redeem his sentence through a cash payment (such as was noted in our examination of Qin law). The second was to follow the code of the gentleman and commit suicide. Unfortunately, the redemption price for his sentence was simply beyond his means. And to commit suicide, while honorable before the world, meant that Sima

Qian would be forswearing his deathbed promise to his father, and act whose unfiliality was past measure. In the end, Sima Qian chose to suffer disgrace, aware that he would be regarded as a coward not only for having failed to take his life honorably, but also for having behaved in this way as a consequence of defending a man who had likewise chosen dishonor over suicide. /+/

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: Wind back two millennia. It is 99 B.C.. On China's northern frontier, imperial forces have surrendered to barbarians. At court, the news is greeted with shock. The emperor is raging. But an upstart official defies court etiquette by speaking up for the defeated general. "He is a man with many famous victories to his credit, a man far above the ordinary, while these courtiers - whose sole concern has been preserving themselves and their families - seize on one mistake. I felt sick at heart to see it," writes Sima Qian in a letter to a friend afterwards. The general had committed treason by surrendering. And Sima Qian had committed treason by defending him. "None of my friends came to my aid, none of my colleagues spoke a word on my behalf," he writes. [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 7, 2012 /*]

“There is an interrogation. Sima Qian tells his friend his body is not made of wood or stone. "I was alone with my inquisitors, shut in the darkness of my cell." At the end he is offered an unenviable choice - death or castration. To his contemporaries, death was the only honourable option but Sima Qian had a bigger audience in mind than the Chinese court of the 1st Century B.C.. He was writing a history of humanity for posterity. Sima Qian's father had been court historian before him and had started the project. On his sickbed, with both of them in tears, the father extracted from the son a promise to complete the epic work. So he chose castration. "If I had followed custom and submitted to execution, how would it have made a difference greater than the loss of a strand of hair from a herd of oxen or the life of a solitary ant?" he wrote. "A man has only one death. That death may be as weighty as Mount Tai or it may be as light as a goose feather. It all depends on the way he uses it." /*\

“But neither in the letter nor in his autobiography can Sima Qian bring himself to describe the horror of castration. He talks instead of going down to the "silkworm chamber". It was already well known that a castrated man could easily die from blood loss or infection so after mutilation the victims were kept like silkworms in a warm, draught-free room. Sima Qian never recovered from the humiliation. "I look at myself now, mutilated in body and living in vile disgrace. Every time I think of this shame I find myself drenched in sweat." But he also wrote that if, as a result of his sacrifice, his work ended up being handed down to men who would appreciate it, reaching villages and great cities, then he would have no regrets even after suffering 1,000 mutilations.” /*\

Sima Qian on the Incident That Led to His Castration

Sima Qian wrote: “Li Ling and I were both officials in the palace, but we had had no opportunity to become friends. Our duties kept us busy in different offices and we had never so much as sipped a cup of wine together or enjoyed the slightest pleasure of friendship. But I observed that he conducted himself with extraordinary self-possession. [Source: “Han shu”67.2725-36 -]

“Now, the troops Li Ling led numbered fewer than 5,000. When they marched deep into the territory of the mounted nomads, they might as well have been marching straight into the Xiongnu court itself. It was like dangling bait in a tiger’s mouth. They challenged the barbarian strength on all sides, facing an army of millions. For over ten days they fought the shanyu, killing more than their own number. The enemy had no time to bear off their dead or succor their wounded. Their pelt-clad leaders trembled in fear. But then the commanders of their left and right divisions sent out a call for every able archer, and all the tribes joined as one to attack Li Ling together, and they surrounded his troops. Yet Li Ling’s army still fought on in retreat for a thousand "li", until all their arrows were gone, their path was blocked, and the armies of relief had failed to arrive. By then the dead and wounded lay in heaps. And still, when Li Ling called out to rouse his army not a soldier failed to leap to the fight, wiping their tears over their bloodied faces. Stifling their sobs they brandished empty bows and braved naked blades, facing north and fighting the enemy to the death, -

“Before Li Ling had been beset a messenger had brought news of his progress to the court and all the ministers and lords had raised their cups and toasted him with cries of “Long life!” When a few days later Li Ling’s report of his defeat arrived, the emperor lost all taste for food and interest in court; his high advisors were beset by fears, with no idea of what to do. Seeing my ruler so depressed and filled with regret, I lost sight of my own humble rank and my heart yearned to convey my frank thoughts to him. I felt that Li Ling had always been a man who led by giving up his own comforts and sharing what he had with those under his command, so that his men would fight for him to the death. Not even the famous generals of antiquity could surpass him. Although he had now fallen in defeat, his intent had clearly been to do the right thing and fulfill his duty to the Imperial House. There was nothing now that he could do, but the destruction that his troops had already wrought upon the enemy was plainly visible for the world to see. -

“I longed to set forth these ideas, but had no way to do so until it happened that I was summoned to give an opinion, and in just this way I spoke of Li Ling’s merits. My hope was to broaden my ruler’s perspective and block the words of jealous-eyed courtiers. But I was myself insufficiently clear and the emperor could not perceive my sense. He saw in my words a critique of General Li Guangli, who had led the relief brigade, and believing that I was speaking as a partisan of Li Ling he had me sent down for prosecution. Not all my earnest loyalty could justify myself to my inquisitors. I was convicted of attempting to delude my ruler and the sentence received imperial approval.” -

“Although the biography of Sima Qian that appears in the “History of the Former Han”indicates that Wu-di later regretted his harshness towards Sima Qian and honored him at court with many signs of personal favor, it is clear from a letter written by the historian shortly before his death that the pain of his disgrace remained keen to the end of his life. Nevertheless, he did persist in fulfilling his promise to his father, and when he died, the “Shiji” was substantially complete. /+/

Sima Qian on His Castration and Why He Submitted To It

Sima Qian wrote: “My family being poor, I was unable to raise funds to redeem my punishment. None of my friends came to my aid, none of my close colleagues spoke a word on my behalf. My body is not made of wood or stone. I was alone with my inquisitors, shut in the darkness of my cell. Whom could I appeal to? You have experienced this yourself, Shaoqing. How was it any different with me? In surrendering alive Li Ling destroyed the reputation of his family. When I followed by submitting to the “silkworm chamber” I became a second laughingstock. Oh, such shame! This is not something I could ever bring myself to recount to an ordinary person.” The “silkworm chamber” refers to the room where castration was inflicted, warmed like silkworm breeding chambers because of the chilling shock to the body that the punishment prompted. [Source: “Han shu”67.2725-36 -]

“My father never attained the tallies of court nobility that could protect his family, and my office of annalist and astrologer was not far in rank from those of the diviners and liturgists, mere amusements for the emperor, retained like singing girls and jesters, counting for nothing in the eyes of the world. If I had followed custom and submitted instead to execution, how would it have made a difference greater than the loss of a strand of hair from a herd of oxen or the life of a solitary ant? For no one would have ranked me with those who die out of loyalty to a code of principle; they would instead have believed that having exhausted my store of wisdom, branded a criminal offender, unable to find any way out of my predicament, I had simply let myself be led to slaughter. And why? Because of the station I had settled on in life. A man dies only once. His death may be a matter weighty as Mount Tai or light as a feather. It all depends on the reason for which he dies. The best of men die to avoid disgrace to their forbears; the next best to avoid disgrace to their persons; the next to avoid disgrace to their dignity; the next to avoid disgrace to their word. And then there are those who suffer the disgrace of being put in fetters; worse yet those disgraced by the prisoner’s suit; worse yet those in shackles; worse yet those who are flogged; worse yet those who with shaven heads and iron chains around their necks; worse yet those who suffer amputations and mutilations. But the very worst disgrace of all is castration. -

“The texts say, “Corporal punishment does not extend to those holding the rank of grandee.” This tells us that an officer cannot but be resolute in his integrity. When a fierce tiger roams deep in the mountains, all animals tremble in fear, but once he has fallen into captivity, through the gradual curtailment of his dignity he will come to wave his tail and beg for his food. Hence if you draw the outline of a jail on the ground, you cannot induce a man of resolve to step within it, and if you carve wood to the image of an inquisitor he will not address it, so set is his intent to have no such encounters. But cross his hands and feet to receive the shackles, bare his back to receive the whip, plunge him in the dark of the dungeon – now he sees his inquisitor and bows his face to the ground, sees the jail guards and gasps in terror. And why? It is the result of the gradual curtailment of his dignity. To have reached such a state and say there is in this no disgrace would be nothing but shamelessness, wholly unworthy of respect. -

Sima Qian on Other Great Men That Suffered

Sima Qian wrote: “King Wen of Zhou was an earl of the Shang state when he was imprisoned in Youli. Li Si was a prime minister and yet he was subjected to all five corporal punishments. Han Xin held the title of King of Huaiyin under the Han emperor, yet he was put in the stocks in Chen, and Peng Yue and Zhang Ao too faced south and held court as kings, yet the one was bound in prison and the other put to death. Lord Jiang had all the Lü clan executed – his power surpassed the Five Hegemons of old – but later he was mewed up in the prosecutor’s jail. The Lord of Weiqi was a great general, yet he had to don the convict’s scarlet gown and wear the wooden shackles. Ji Bu spent a term as the slave of the Zhu family, and Guan Fu was disgraced in prison.

“This being understood, the conduct of these men is nothing to wonder at. Once having failed to do away with themselves before falling into the clutches of the law, and having then been worn down by degrees between the whip and the bastinado, committing suicide on principle had moved far beyond their reach. This is surely why the ancients viewed corporal punishment for men of grandee rank as excessive. “By nature, no man will fail to cling to life and avoid death, be concerned for the welfare of his parents, and look after and protect his wife and children. When a man who is passionate about righteousness acts contrary to it, it is due to the force of such inescapable dispositions. Now, I had the misfortune to lose my father and mother early. I have no brothers and so stand alone, without such family – and you can see, can’t you, Shaoqing, how little I had attended to the good of my wife and children in speaking out. -

“But if a brave man will not always die for a code of principle, so too a coward may find great resolve if what is right is dear to him. Though I may be a coward who could cling to life by self-serving conduct, surely I know the difference between flagrant right and wrong. How could I have plunged myself into the ignominy of bring tied and bound? Even a captive slave-girl is capable of putting an end to herself, and surely I could have done so as well, had it been the inescapably correct path. The reason why I bore the intolerable and clung to my life, refusing to release myself from the filth into which I had been cast, was the remorse I felt at the prospect of leaving the achievement dearest my heart incomplete, quitting the world like a vulgar nonentity with the written emblem of my lifework unrevealed to posterity. /+/

Sima Qian, the Historian

Dr. Eno wrote: “The task that Sima Qian undertook in writing a universal history was prodigious. No one had attempted anything like it before. He had to plan the organization of the text and read widely to become fully informed about the outline of the past. But more than that, he had to search out evidence. There existed no catalogue of texts, no libraries, no bibliographies or footnotes. He must have unearthed some of his evidence in the imperial archives. For example, he draws heavily from the "Zuozhuan", which was at this time unknown in China. Sima Qian probably unearthed the base texts of the "Zuozhuan" by searching through the palace archives in Chang’an, where bolts of silk texts and strings of inscribed bamboo strips had long been piled. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“But in addition to reading what was available at the capital, Sima Qian traveled all over China searching for texts, inquiring about local traditions, and journeying to the places where events had occurred so that he could better understand exactly what had transpired. As he collected evidence, Sima Qian carefully sifted it for reliability. In cases where evidence was abundant, he formed judgments concerning the actual course of events and eliminated evidence that appeared to him to be fabricated. In cases where evidence was very scarce, such as in the biography of Laozi, he simply brought together all available traditions, alerted readers as to his own uncertainty, and left the judgment to the future. Sima Qian viewed this sort of judicious skepticism as part of the Confucian tradition, for Confucius himself had, in the “Analects” , praised historians who were willing to put aside what was of doubtful veracity and leave blanks in their accounts rather than perpetuate gossip. /+/

Sima Qin’s Effort to Ascertain “The Truth”

Dr. Eno wrote: “Here we can also ask to what degree Sima Qian may have followed the practices of Confucius in editing the “Spring and Autumn Annals”, as they were understood during the early Han. Confucius, the tradition claimed, had viewed history writing as a means of conveying the Dao rather than as a means of preserving facts. He had actually tampered with the completed annals of the court of Lu, altering the words of the scribes in order to enable the reader to see through the facts to the “Truth.” When the case of the “Monograph on the "fengshan" Sacrifices” was discussed earlier, we noted that it was possible that its grossly unflattering portrait of Wu-di could have been a product of Sima Qian’s personal resentment. Alternatively, the material could be true, or the chapter could be a later forgery, inserted in the “Shiji” to support latter day court factions opposed to the example of Wu-di. While we cannot determine the answer with certainty, we can note one additional factor which makes it less likely that the “Monograph” was part of an attempt by Sima Qian to model his work on the “Spring and Autumn Annals”. /+/

“One of the features of the “Annals”, once again, as it was understood in the Han, was the surpassing subtlety of its alterations of literal history. The change of a preposition here, the choice of a different form of appellation there – these were the methods that Confucius had supposedly used to embed moral meaning in history. That was why “Annals” studies had generated exegetical schools that fought tooth and nail over the significance of every exclamatory particle in the text. Confucius was writing in times of trouble, when speech was dangerous. He wrote between the lines for the “sages” of the future, a message to utopia from hell. /+/

“The portrait of Wu-di that emerges from the “Monograph” hardly conforms to those criteria, and if Sima Qian were indeed writing history as a form of protest against autocratic tyranny – with which he had profound experience – he would surely have been more careful. And he was careful. Close examination of other chapters in the text does indeed reveal places where Sima Qian, by an apt but unstressed phrase, conveys very pointed judgment of the people and events about which he writes. One example would be the closing remark in his discussion of Wen-di, where he praises as "ren" Wen-di’s restraint in declining to stage the "fengshan" sacrifices. What more pointed rebuke of Wu-di’s attitude towards his religious role need there be? The historian’s judgment is plain enough, and the subtlety of the remark resonates with the training that Sima Qian would have received from Dong Zhongshu. /+/

“An example of the ways in which such notions of historiography may have influenced the actual narratives themselves may perhaps be seen in the biographical accounts of Xiang Yu and Liu Bang. Both portraits include many contradictions. Some readers claim that we can read from these Sima Qian’s preference for one or the other of these men, and that would be bias indeed. But perhaps what we see is more subtle again. It is more consistent with the narratives to see Sima Qian as attempting to select evidence that illustrates all aspects of the personalities of these two adversaries without selecting between them, instead marking clearly what is praiseworthy in each and what may be deplored. /+/

“In Sima Qian’s portrait of Liu Bang, for example, we read both about his personal obnoxiousness and also about his modesty and willingness to give credit to others. We see his bravery in denouncing Xiang Yu’s misbehaviors, point by point, to his face, but we also see his matchless cowardice in thrice kicking his own children out of his chariot as he fled from his pursuers after the battle of Pengcheng. What emerges from this is an image of the Han founder that, while perhaps including as much legend as fact, may actually capture the complexity of the man as he was, while allowing the reader to view him through the ethically appraising eye of the historian.

Sima Qian’s Historical Writings

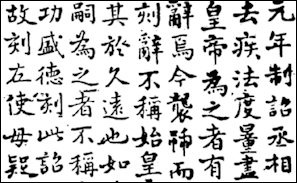

Passage from the Shiji

Sima Qian wrote: "Probing into events, connecting their narrative flow, finding patterns governing victory and defeat, prosperity and decay, I have composed 10 historical tables, 12 royal annals, eight monographs, 30 genealogies of noble houses, 70 biographical accounts - 130 chapters in all. I have sought, through examination of the interface of heaven and man, and comprehension of change from past through present, to found a new tradition of philosophy."

According to Carrie Gracie of the BBC News: “What is special about Sima Qian's history is that, even when he wrote about the court, it was not just flattery. Here is his verdict on an emperor from the Shang dynasty 1,000 years earlier: "Emperor Zhou's disposition was sharp, his discernment was keen, and his physical strength excelled that of other people. He fought ferocious animals with his bare hands. He considered everyone beneath him. He was fond of wine, licentious in pleasure and doted on women… He then ordered his Music Master to compose new licentious music and depraved songs. By a pool filled with wine, through meat hanging like a forest, he made naked men and women chase one another and engage in drinking long into the night." The emperor had critics turned into mincemeat, and nobles who were not up for the party roasted alive. [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 7, 2012 /*]

“Zhou was a good illustration of a theory Sima Qian had about dynastic change, as Frances Wood, curator of the Chinese collection at the British Library, explains. "He introduced the idea… that dynasties begin with the very virtuous and noble founder, and then they continue through a series of rulers until they come to a bad last ruler, and he is so morally depraved that he is overthrown." No suprises - Zhou was the last of the Shang dynasty. Sima Qian thought the purpose of history was to teach rulers how to govern well.

The Records of the Grand Historian almost didn’t see the light of day and only did after powerful people it might have hurt had passed on. After Sima’s death, his daughter risked her own safety to hide his secret history. And two emperors later, his grandson took another risk in revealing the book's existence. The rest, as they say, is history.

Sima Qian’s Accomplishments as a Historian

Sima Qian wrote: “It has been over twenty years since I assumed the yoke of service to carry forward my father’s merit at court. My own view is this: First, I have not been able to accomplish great things through loyal devotion or great acts of faithfulness, not to earn a reputation for exceptional advice or talent in service to my enlightened lord. Second, I have not been able to make good the court’s lapses or supply its wants, nor to attract worthy men or advance the able, nor to bring to light men of wisdom who have withdrawn to the cliffs and caves. And in foreign service too, I have been unable to win merit by serving in the ranks, attacking cities, or fighting in the field, beheading enemy commanders or capturing their banners. And even in the least of things I have no accomplishments, never rising to high office or salary through years of labor, bringing no glory or favor to family and friends. I have nothing to show in any of these four respects. You can see therefore how I have contributed nothing of value, merely bending to the general will and attempting to give no offense. [Source: “Han shu”67.2725-36 -]

“Formerly, when I held the rank of a lower grandee, I would sometimes participate in the minor deliberations of the outer court. But I did not then stand on principle or speak what was on my mind. So if now, as a mutilated slave sweeping the floors, a weed defiling the court, I should with earnest brow raise my head to set forth my views of truth and error, would this not be an insult to the court and to the gentlemen of this age? Oh, alas! What could there be for a man like me to say – what could there be? -

“How this all came to be is not easy to explain. As a youth I relied on my untutored abilities and upon coming of age I had earned no recognition from the people of my district. However, on account of my father’s service I was so lucky as to have the emperor call upon me to contribute my shallow talents, allowing me to come and go within the palace precincts. I believed the old saying that one can’t see the sky carrying a platter on one’s head, so I broke off relations with friends and neglected family affairs, day and night devoting the weak force of my talents to my official duties, hoping to gain the confidence and approval of the emperor. But events did not unfold as I had planned. I committed an egregious error. “ -

Sima Qian’s Letter to Ren An

Dr. Eno wrote: “Shortly before he died, a personal friend of Sima Qian named Ren An (his polite name was Ren Shaoqing) addressed to him a plea for help. Ren An had been caught up in the early stages of the witchcraft scandal of 91 B.C. and was under indictment for a capital offense. He hoped that Sima Qian would use his influence at court to help him evade the penalty to which he had been sentenced. In reply, Sima Qian wrote Ren An a long letter, explaining why he did not believe he would be able to help, and detailing the history of his own sad encounter with Wu-di’s vengeance. Together with the concluding chapter of the “Shiji”, which Sima Qian devoted to the story of his own life, the letter to Ren An is the earliest piece of sustained autobiographical writing that we possess from China The letter includes a number of extended passages that appear nearly verbatim in Sima Qian’s “Shiji” autobiography, and so it would seem, if our record of it is indeed accurate, that although it was a personal letter to a friend, it was also represents Sima Qian’s reflective effort to portray and justify himself to the world. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Ren An did not manage to evade the consequences of the scandal, and he was executed soon after Sima Qian’s letter was written. Sima Qian himself probably died within the year. The letter that he wrote somehow was conveyed years later to the hands of Ban Gu, the author of the "History of the Former Han". Ban Gu, who was himself engaged in emulating Sima Qian’s example of writing a great history, included the entire letter in his biography of Sima Qian. /+/

See Sima Qian's Letter to Ren An [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated June 2022