GUANGZHOU (CANTON)

Guangzhou (130 kilometers north of Hong Kong) is China's fifth largest city after Shanghai, Beijing. Chongqing and Tianjin, with 13.2 million people (two thirds of them residents and one third of them migrants). It has long a long history as a trading port and long been regarded as the most Westernized city in China. Trade between China and Europe was largely conducted from here. In the Mao era people picked up Hong Kong radio and television stations and could buy international newspapers on the streets.

Guangzhou (formerly Canton or Kwangchow) is the capital of Guangdong Province and the gateway to southern China. Over 2,000 years old, it lies at the heart of one of the world's busiest and most thriving economic regions: the Pearl River Delta and has close contact with Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Guangzhou is (1,850 kilometers (1,150 miles) south of Beijing and 1450 kilometers (900 miles) southwest of Shanghai.

Metropolitan Guangzhou encompasses an area of over 11,650 square kilometers (4,500 square miles). The city proper has an area of 54 square kilometers (21 square miles). The a population of the city is 11.5 million while the metro area is home to about 24 million people, including several million migrant workers.

See Separate Articles GUANGDONG PROVINCE factsanddetails.com ; GUANGZHOU TOURISM, SIGHTS, ENTERTAINMENT AND TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com ; SIGHTS IN GUANGZHOU factsanddetails.com NEAR GUANGZHOU factsanddetails.com ; SHENZHEN: SKYSCRAPERS, MINIATURE CITIES AND CHINA’S FASTEST-GROWING AND WEALTHIEST CITY factsanddetails.com

History of Guangzhou

According to legend Guangzhou was surrounded by barren land before five men riding five rams came to the city pronging prosperity. The legend is immortalized with a statue that stands at the center of Guangzhou. As early as the 7th century Guangzhou had 200,000 foreign resident, including Arabs, Persians, Indians, Africans and Turks. It was the main trading center between China and Europe before Opium Wars and was where the events that sparked the Opium Wars (1839-42) took place

A settlement now known as Nanwucheng was present in the Guangzhou area by 1100 B.C. A description of the place in the 4th century B.C. said it was little more than a stockade of bamboo and mud. In 214 B.C., Panyu was established on the east bank of the Pearl River to serve as a base for the Qin Empire's first failed invasion of the Baiyue lands in southern China. In 113 B.C., through marriage, Panyu was absorbed into China’s Han Dynasty.

In the Communist era, Guangzhou area was a focal point of Deng Xiaoping economic reforms. In the early 1980s, not long after Mao’s death and the end of the Cultural Revolution, Deng and his allies promoted China’s successful experiment with the free markets in Guangdong Province. In 1992, during his famous Southern Tour, Deng held up the achievements to symbolically challenge conservatives within the Communist Party who threatened his reforms. “People here are proud of Guangdong’s progressive streak,” Ding Li, a senior researcher at the Guangdong Academy of Social Sciences, told the New York Times. “We are also happy to be far away from Beijing — and the least controlled by it.”

This set of a huge surge or economic growth. Between 2001 and 2006, 58 buildings 30 stories or more were completed, under construction or proposed and much of the city was torn up by construction of a subway. In January 2007, Guangzhou became the first Chinese city to reach a per capita income of $10,000, often seen as the threshold for developed status, and considerably more than the $1,740 per capita income of the China at that time. Later the figure was lowered to $7,800 because the $10,000 figure only counted the city's 7.5 million residents and not the 3.7 migrants that lived there.

The city is now well-connected by high-speed railroads and subway lines. Progress has been made in the high number of flyovers crossing the Pearl River and the number of transmission lines that dot the city. In preparation for the Asian Games in 2010, a large amount of money was spent on cleaning up Pearl River and creating more green spaces.

Canton and Maritime Trade During the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), thousands of foreigners came and lived in numerous Chinese cities for trade and commercial ties with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Bengalis, Sinhalese, Khmers, Chams, Jews and Nestorian Christians of the Near East, and many others. In 748, the Buddhist monk Jian Zhen described Guangzhou as a bustling mercantile center where many large and impressive foreign ships came to dock. He wrote that "many big ships came from Borneo, Persia, Qunglun (Indonesia/Java)...with...spices, pearls, and jade piled up mountain high", as written in the Yue Jue Shu (Lost Records of the State of Yue). In 851 the Arab merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir observed the manufacturing of Chinese porcelain in Guangzhou and admired its transparent quality. He also provided a description of Guangzhou's mosque, its granaries, its local government administration, some of its written records, the treatment of travelers, along with the use of ceramics, rice-wine, and tea. [Source: Wikipedia +]

During the An Lushan Rebellion Arab and Persian pirates burned and looted Guangzhou in 758, and foreigners were massacred at Yangzhou in 760. The Tang government reacted by shutting the port of Canton down for roughly five decades, and foreign vessels docked at Hanoi instead. However, when the port reopened it continued to thrive. In another bloody episode at Guangzhou in 879, the Chinese rebel Huang Chao sacked the city, and purportedly slaughtered thousands of native Chinese, along with foreign Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Muslims in the process. Huang's rebellion was eventually suppressed in 884. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Chinese engaged in large-scale production for overseas export by at least the time of the Tang. This was proven by the discovery of the Belitung shipwreck, a silt-preserved shipwrecked Arabian dhow in the Gaspar Strait near Belitung, which had 63,000 pieces of Tang ceramics, silver, and gold (including a Changsha bowl inscribed with a date: "16th day of the seventh month of the second year of the Baoli reign", or 826, roughly confirmed by radiocarbon dating of star anise at the wreck). [Source: Wikipedia +]

Beginning in 785, the Chinese began to call regularly at Sufala on the East African coast in order to cut out Arab middlemen, with various contemporary Chinese sources giving detailed descriptions of trade in Africa. The official and geographer Jia Dan (730–805) wrote of two common sea trade routes in his day: one from the coast of the Bohai Sea towards Korea and another from Guangzhou through Malacca towards the Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka and India, the eastern and northern shores of the Arabian Sea to the Euphrates River. +

See Separate Articles MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com and MARITIME-SILK-ROAD-ERA SHIPS, EXPORT PORCELAINS AND SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Early Europeans in Canton Area

As elsewhere in Asia, in China the Portuguese were the pioneers, establishing a foothold at Macao (Aomen in pinyin), from which they monopolized foreign trade at the Chinese port of Guangzhou (Canton). Soon the Spanish arrived, followed by the British and the French. Trade between China and the West was carried on in the guise of tribute: foreigners were obliged to follow the elaborate, centuries-old ritual imposed on envoys from China's tributary states. There was no conception at the imperial court that the Europeans would expect or deserve to be treated as cultural or political equals. The sole exception was Russia, the most powerful inland neighbor.

According to Columbia University's Asia for Educators: “Many Europeans had contact with China over the centuries. When Marco Polo traveled to China in the thirteenth century, he found European artisans already at the court of the Great Khan. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, priests such as the Italian Matteo Ricci journeyed to China, learned Chinese, and tried to make their religion more acceptable to the Chinese. These contacts were made usually by individual entrepreneurs or solitary missionaries. Although some Western science, art, and architecture was welcomed by the Qing court, attempts to convert Chinese to Christianity were by and large unsuccessful. More importantly, the Chinese state did not lend its support to creating a significant number of specialists in Western thinking. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, consultants Drs. Madeleine Zelin and Sue Gronewold, specialists in modern Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu]

In 1636, King Charles I authorized a small fleet of four ships, under the command of Captain John Weddell, to sail to China and establish trade relations. At Canton the expedition got into a firefight with a Chinese fort. Other battles occurred after that. The British blamed the failure in part on their inability to communicate.

In 1820, China accounted for 29 percent of the world's gross domestic product and China and India together accounted for more than half of the world's output. Foreigners thought they could get rich in China. There is a famous story about an 18th century Englishman who thought he could make a fortune in the textile business by convincing every Chinese person to extend the length of their shirt tails by one inch. A Harvard historian told Smithsonian magazine, “People signing on to voyages to Asia weren't just looking to make a living, They were looking to make it big."

See Separate Article EUROPEAN PRESENCE IN CHINA IN THE MING AND EARLY QING DYNASTY (16th-18th CENTURIES) factsanddetails.com

Trade in Canton

Up until the late 17th century, Western traders were allowed to conduct business only in Macau, a Portuguese enclave 75 miles south of Canton. In 1685, the powerful Qing emperor Kangxi was persuaded that he might profit from an expansion in trade and thus he permitted Western merchants to trade in Canton itself, which at that time was a bustling city along the Pearl River with about a million people.

Trade with Europe expanded in the 18th and 19th centuries. Favorable concessions were given to French and British traders, who set up shop on the East Coast of China. The reasoning was that if they were preoccupied with trade they would not cause mischief. Failure to keep pace with Western arms technology and the isolation of the Qing dynasty made it vulnerable to attacks from European weapons and exposed China to European expansion.

According to Columbia University's Asia for Educators: ““Direct oceanic trade between China and Europe began during the sixteenth century. At first it was dominated by the Portuguese and the Spanish, who brought silver from the Americas to exchange for Chinese silks. Later they were joined by the British and the Dutch. Initially trading took place at several ports along the Chinese coast, but gradually the state limited Western trade to the southern port of Canton (Guangzhou). Here there were wealthy Chinese merchants who had been given monopoly privileges by the emperor to trade with foreigners.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, consultants Drs. Madeleine Zelin and Sue Gronewold, specialists in modern Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu]

The lives of Western traders in Canton were greatly restricted. They could only come to Canton half of the year and then were forced to live in ghettos outside Canton's walls and were not permitted to bring their families (who were required to stay in Macau). They were also forbidden from boating on the river and trading with anyone other than authorized representatives of the Emperor, who tried to bilk the foreigners for everything he could get. The "foreign devils" worked out of offices called "factories" where the local people came by to stare at their big noses. Their vessels were required to anchor ten miles downstream on the Pearl River at Whampoa.

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “Foreigners— even on trade ships — were prohibited entry into Chinese territory. The exception to the rule was in Canton, the southeastern region centered on modern-day Guangdong Province, which adjoins Hong Kong and Macao. Foreigners were allowed to trade in the Thirteen Factories district in the city of Guangzhou, with payments made exclusively in silver. The British gave the East India Company a monopoly on trade with China, and soon ships based in colonial India were vigorously exchanging silver for tea and porcelain. But the British had a limited supply of silver. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

Merchant guilds trading with foreigners were known as "hongs," a Westernization of hang, or street. The original merchant associations had been organized by streets. The merchants of the selected hongs were also among the only Chinese merchants with enough money to buy large amounts of goods produced inland and have them ready for the foreign traders when they came once a year to make their purchases.

“The Chinese court also favored trading at one port because it could more easily collect taxes on the goods traded if all trade was carried on in one place under the supervision of an official appointed by the emperor. Such a system would make it easier to control the activities of the foreigners as well. So in the 1750s trade was restricted to Canton (Guangzhou), and foreigners coming to China in their sail-powered ships were allowed to reside only on the island of Macao as they awaited favorable winds to return home."

Canton Opium Trade and the Opium Wars

The British East India Company built up a huge debt for silk, tea and lacquerware.The unfavorable balance of trade between Britain and China and resentment over China's restrictive trading practices set in motion the chain of events that led to the Opium Wars When the United Kingdom could not sustain its growing deficits from the tea trade with China (partially also because the Qing imperial court refused to open the Chinese market for British goods), it smuggled opium into China.

The British had few things that the Chinese wanted so opium, grown in India, was introduced as a new medium of exchange. Opium was the perfect commodity for trading. It didn't rot or spoil, it was easy to transport and store, it created its own market and it was highly profitable. The standard measurement for opium was a 135-pound chest, which sold for as much as a thousand silver dollars. The Chinese referred to opium as "foreign mud" or "black smoke" and sometimes called it yan, which entered the English language as "yen" ("a sharp desire or craving"). [in Chinese, opium has usually been called ya-pian, a transliteration. It was also called Afurung, another, more elegant transliteration, and dayen, big smoke. Yan is the Cantonese pronunciation of Mandarin yin, which means addiction, not opium. Mandarin yen means smoke, as in dayen. Different words."

In December 1838, after years of debate and ineffective action, the emperor appointed Lin Zexu as commissioner in Canton with instructions to stamp out the opium trade. According to Columbia University's Asia for Educators: ““Lin was able to put his first two proposals into effect easily. Addicts were rounded up, forcibly treated, and taken off the habit, and domestic drug dealers were harshly punished. His third objective — to confiscate foreign stores and force foreign merchants to sign pledges of good conduct, agreeing never to trade in opium and to be punished by Chinese law if ever found in violation — eventually brought war." [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu]

The First Opium War (1839-42) began in March 1839, when Lin Zexu, ordered British merchants to stop trading opium "forever" and surrender "every article" of opium in their possession. The Chinese navy surrounded opium-carrying British ships near Canton, cutting off their food supply, while Lin prohibited all foreigners from leaving Canton, in effect holding them hostage, until the opium was turned over. [Source: Stanley Karnow, Smithsonian magazine]

The British held off the Chinese for six weeks until British naval officer Charles Elliot advised the British merchants to hand over their entire inventory of opium, some 20,000 chests (2.7 million pounds, about 95 percent British and 5 percent American), telling them that the British government promised to reimburse them at the going prices. The merchants were willing to go along with the offer, figuring they would get their money and that a shortage would only boost the demand and the price of the drug.

See Separate Articles OPIUM WARS PERIOD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com

People from Guangzhou

People from Guangzhou have a reputation for being ambitious, good at business and good cooks. A slogan commonly written on the billboards in Guangzhou is Look to the Future. The Chinese word for "future" sounds almost the same as the one for "money," and many Chinese say Guangzhou's real slogan is Look to the Money!

Cantonese are regarded as very materialistic. One Chinese man told The New Yorker, “All people think is, “I just what to get rich." The richer you get, the more respect you'll get. And the first people to get rich n the 1990s, were the Cantonese. Then people in other provinces started to copy the Cantonese life style, part of which is to eat a lot of seafood to show how much money you have."

The people from Fujian and Guangdong are regarded as hard working and are famous for their entrepreneurial and counterfeiting skills. Many of the Chinese in Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the United States are decedents of people that emigrated from Fujian and Guangdong Provinces. Fujians and people from Guangzhou and Guangdong have traditionally been among the most ambitious go-getters in China. Many of the rich Chinese that made their fortune in the Hong Kong, United States and Southeast Asia have been Fujians or people from Guangdong..

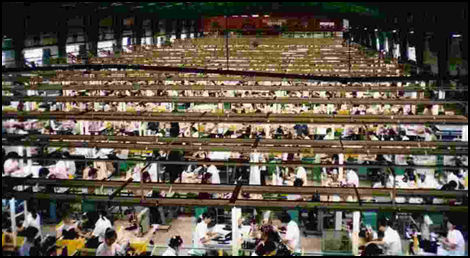

Nike factory

Economy of Guangzhou and the Pearl River Delta

Pearl River Delta (northwest of Hong Kong) embraces the industrial towns of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Huizhou, Dongguan, Foshan, Jiangmen, Zhongshan and Zhuia. The region has a population of around 120 million, made up of permanent residents and a "floating population" of migrant laborers. If Hong Kong and Macau are included the Pearl River Area were an independent country it would be East Asia's forth largest economy and its second largest exporter. The Pearl Delta area exports as much as Mexico or South Korea.

China’s first Special Economic Zones (SEZ) opened here in Shenzhen and Zhuhai — as well as in Shantou in Guangdong and Xiamen (Amoy) in Fujian Province — in 1979. In the beginning factories here did most of the manufacturing once performed in Hong Kong. In the early 2000s, the Pearl River Industrial Area drew an astonishing $2 billion of foreign investment a month and accounted for one third of China's exports. Investors and companies are still attracted by cheap labor, good managers and easy access to the outside world. Labor-intensive, export-oriented industries include makers of toys, shoes, Christmas decorations, small gifts and textiles. More advanced factories assemble computer keyboards, televisions, watches motorcycles, and dishwashers. IBM, Samsung, Honda and Wal-Mart are among the companies tat have a major stake here,

Special Economic Zones in Guangdong Province, the Hong Kong area and the Pearl River Delta is sometimes referred to as the “world's factory." As of 2006, there were more than 200,000 factories here. At that time the factories in and around Shenzhen, Dongguan Guangzhou and the Pearl River Delta annually churned out $36 billion worth of goods, nearly a third of all the goods that are exported abroad. They produced 40 percent of the playthings sold in the U.S., including Barbies, Ninja Turtles and Mickey Mouse.

There area now embraces Nansha Port Area in the Port of Guangzhou and large container ports in Shenzhen at Guangzhou. There were plans for a tunnel linking Shenzhen and Zhuhui. But in the end it was decided to build 32-kilometer Shenzhen–Zhongshan Bridge connecting those two major cities and expected to be completed in 2024. As the Pearl River itself: in Guangzhou (Canton) it is such a thick dark soup it looks like one could walk across it.

Guangzhou's industrial, commercial, and residential areas have greatly expanded, particularly to the south and east of the city. Goods made in the Guangzhou area are sold all over the world marketed in nearly all countries. Light industrial manufacturing, including textiles, shoes, toys, furniture, and exportable consumer products, accounts for most of these exports. Principal heavy industries include shipbuilding, sugar refining equipment, and tool and motorcycle manufacturing. The metropolis has several auto factories, and aspires to be China's Detroit. The region between Guangzhou and Hong Kong is home to Special Economic Zones like Shenzhen and Zhuhai. The highway between the two cities has been described as one long construction project and some people joke that the local bird is the crane. The Pearl River Delta is a fertile agricultural region supporting two rice crops yearly. Agricultural mainstays traditionally produced here include jute, sugarcane, oil-producing plants, pigs, chickens, ducks, and fish.

Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge: World's Longest Sea Bridge

The Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge and Tunnel — a 55-kilometer-long bridge linking Hong Kong Island to mainland China via Macau — opened in 2018, years after it was supposed to. Stretching more than 55 kilometers (34 miles), series of bridges and undersea tunnels links Hong Kong and Macau with Zhuhai, a city on the southern coast of Guangdong province in mainland China located in the Pearl River Delta.

The sixth longest bridge in the world and world’s longest sea bridge, it now links Hong Kong’s New Territories, Lantau Island and Hong Kong International Airport with Macau to the west and its and sister city Zhuhai, which sits just over the border in mainland China. The Pearl River Delta is a huge area and spanning it and the open water around it is an unparalleled engineering feat. [Source: Megan Eaves, Lonely Planet, October 23, 2018]

Megan Eaves of Lonely Planet wrote:“Traffic on the bridge has been restricted to vehicles with special permits, meaning that regular drivers from Hong Kong and Macau cannot make the crossing in their own private cars. However, a shuttle bus service connects to Hong Kong port, meaning travellers can now avail of regular bus crossings between the two cities. Travellers will continue to have to pass border control and have their passports stamped or visas checked between Macau and Hong Kong. Travellers planning to visit Zhuhai can obtain 24hr visas at the border, but anyone wishing to stay longer or travel further afield in mainland China will need to apply for a visa in advance from the Chinese embassy in their home country, or through a service in Hong Kong.”

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Province maps from the Nolls China Web site. Photographs of places from 1) CNTO (China National Tourist Organization; 2) Nolls China Web site; 3) Perrochon photo site; 4) Beifan.com; 5) tourist and government offices linked with the place shown; 6) Mongabey.com; 7) University of Washington, Purdue University, Ohio State University; 8) UNESCO; 9) Wikipedia; 10) Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in May 2020