CRITICS OF THE GAOKAO

Studying hard in the 1920s Criticism of the gaoko — China’s university entrance exam — has grown and debate over it has become more heated in recent years. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “ Critics say the exam promotes the kind of rote learning that is endemic to education in China and that hobbles creativity. It leads to enormous psychological strain on students, especially in their final year of high school. In various ways, the system favors students from large cities and well-off families, even though it was designed to create a level playing field among all Chinese youth. " Dissatisfaction with the gaokao system is why some families choose to send their children abroad to study.

[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times June 30, 2012]

In May 2012, a 12-minute television segment railing against the exam by Zhong Shan, a well-known talk show host in Hunan Province, gained popularity on the Web and became a focal point for fury against the gaokao in particular and the Chinese educational system in general. Also widespread on the Internet were photographs taken in a Hubei Province classroom of students hooked up to intravenous drips. Perhaps most shocking to the public was the story of Liu Qing , a student from Xian, Shaanxi Province, whose family and teachers hid from her for two months the fact that her father had died so as not to upset her before the exam. Ms. Liu, according to reports in the Chinese news media, did not hear the news about her father until after she had completed the test. “We Chinese are indeed the most intelligent people in the world,” Mr. Zhong said near the end of his widely broadcast screed. “Is there no way at all we can avoid having the younger generation, the future of our nation, grow up in such a fearful, desperate and cruel atmosphere?”

See Separate Articles:THE GAOKAO: THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY ENTRANCE EXAM factsanddetails.com GAOKAO ESSAYS factsanddetails.com ; EXAMS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM: LAWS, REFORMS, COSTS factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA: RULES, REPORT CARDS, FILES, CLASSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Gaokao: A Personal Journey Behind China's Examination Culture” by Yanna Gong (2013) Amazon.com; “Gaokao Roadmap: Triumphing in China's College Entrance Exam” by Zhang Wei (2023) Amazon.com “Meritocracy and Its Discontents: Anxiety and the National College Entrance Exam in China” by Zachary M. Howlett (2021) Amazon.com; “Unveiling the Secrets of Gaokao Essays to Stand Out in IB Chinese Exams: Compilation of Chinese Gaokao Essay Topics, Sample Essays, and Writing Techniques Year 2023 Related to: IB Chinese Exam” by David YAO Amazon.com; “Government Education and the Examinations in Sung China, 960-1278" by Thomas H. C. Lee Amazon.com; “Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China” by Benjamin A. Elman Amazon.com

Defenders of the Gaokao

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian:“In China there are no illusions about the system being perfect. But, ultimately, most people support it, or at least see no alternative. “China has too many people,” is a common refrain, used to excuse everything from urban traffic to rural poverty. Given the intense competition for finite higher education resources, the argument goes, there has to be some way to separate the wheat from the chaff, and to give hardworking students from poorer backgrounds a chance to rise to the top. [Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: ““Standardized testing is common throughout the world, and students and parents in nations like the United States, Britain and France also complain loudly about the weight that admissions committees at universities place on such tests. But the admissions process in those countries is still considered much more flexible than that in Asian nations. The emphasis on entrance exams in China, South Korea and Japan induces widespread fear and frustration, leading more and more parents from elite families to look for alternatives, like sending their children abroad. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times June 30, 2012]

Defenders of the gaokao, which has its roots in the imperial exam system, say the test is a crucial component in a meritocracy, allowing students from poorer backgrounds or rural areas to compete for spots in top universities. Nevermind that the odds are heavily against those students, since a quota system based on residency means it is much easier for applicants in cities like Beijing and Shanghai to get into universities there, which are generally considered the best in China. Peking University, among the most prestigious, does not release admission rates, but Mr. Zhong said on his television program that a student from Anhui Province had a one in 7,826 chance of getting into Peking University, while a student from Beijing had one in 190 odds, or 0.5 percent. (Harvard had a 5.9 percent acceptance rate this year.)

Zhang Qianfan, a law professor Peking University who has studied the education system, said the main problem was the lack of slots at universities. Despite a boom in university construction in China, there is still a shortage. In 2012 there were seven million university slots, two million short of the number of gaokao test takers. The gap was much wider in 2006 — there were 5.3 million slots then for 9.5 million test takers. The drop in the number of students taking the gaokao can be attributed to demographic trends in China and the rise in the number of students opting to study abroad.”Many people are harsh critics of the gaokao, but I think they somewhat miss the most crucial point, which is that the supply from decent academic institutions falls short of the demand from the public,” Mr. Zhang said.

Stress and Pressure of the Gaokao

The test-taking season is so stressful it is referred to as "Black July." Newspapers run many stories about students who have health problems while cramming of the test. Hepatitis and weight problems are especially common. In 2000, there was a news report about a schoolboy who bludgeoned his mother to death for badgering him about studying. On test day test takers make sure they show up on time. Parents crowd around the school where the test is held and stand around with blank expressions waiting for the test to finish. Schools that prepare students for exams is a big business.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “Even supporters of the gaokao system acknowledge the level of anxiety involved. It is not uncommon for Chinese to have recurring nightmares about cramming for and taking the gaokao years after they have graduated from university. Many schools in China set aside the final year of high school as a cram year for the test. Taoyuan Yang, a student in Kunming, said he spent 13 hours a day in his senior year studying, and his parents even rented an apartment for him near his school so he would not have to waste time traveling back and forth to his parents’ home. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times June 30, 2012]

“When I was getting close to the test, pretty much all I did besides eat and sleep was study,” Zhao Xiang, a high school graduate from Zunyi, Guizhou Province, said in an Internet chat interview. He said students’ lives before the gaokao were full of suffering: “Sometimes it was pressure from my family, sometimes it was the expectations from my teacher, sometimes it was pressure from myself. I was constantly in a really bad mood in the period before the gaokao. I was really confused.”

One student who did poorly the first time he took the gao kao told the New York Times the night before the exam, he lingered at his parents’ bedside, unable to sleep for hours. I was so nervous during the exam my mind went blank, he said. He scored 432 points out of a possible 750, too low to be admitted even to a second-tier institution. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, June 13, 2009]

“Silence reigned in the house for days afterward. My mother was very angry, he said. She said, “All these years of raising you and washing your clothes and cooking for you, and you earn such a bad score.”...I cried for half a month.Then the family arrived at a new plan: He would enroll in a military-style boarding school in Tianjin, devoting himself exclusively to test preparation, and retake the test.”

Lasting Impact of the Gaokao

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker: Most of my” university “students seemed traumatized in some way by the gaokao experience. A few described having had suicidal thoughts, and one boy wrote a personal essay about being hospitalized for stress-related heart trouble. In 2020, I asked students in a freshman class how they had reacted to learning their gaokao scores, and seventeen out of eighteen said they had been disappointed. Leslie and I sometimes joked that in America every child is a winner; in China, every child is a loser. [Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, May 9, 2022]

“Everything came down to numbers, because that’s the principle of the gaokao... When a student applies to university, scores are all that matter — no teacher recommendations, no list of extracurriculars. One attraction of scupi was that its cutoff gaokao score was lower than that of other departments. In order to enter scupi [Hessler’s program] in the fall of 2019, a student in Sichuan Province needed 632 points out of 750. The next-lowest cutoff was 649, which allowed a student to enter a number of less prestigious departments, including Water Resources, Sanitation Testing and Quarantine, and Marxism. English was 660, econ 663, math 667. The university’s Web site listed the numbers, and status was measured accordingly. The ultimate campus élite, the Brahmins of Sichuan University, occupied the School of Stomatology. At first, this mystified me — why such a fuss about oral medicine? But the School of Stomatology at Sichuan University’s West China Medical School is recognized as the best in the nation, and it took a remarkable 696 points to enter its program in clinical medicine. Other undergrads resented the stomatologists; my students said they held themselves apart. If asked about his major, a stomatologist might coyly avoid answering, like a Harvard grad who says he went to school “in Boston.”

“Yet students generally supported the Chinese system. Each semester, my freshman classes debated whether the gaokao should be significantly changed, and the majority answered in the negative. Many came to the same conclusion in argumentative essays. (Spring of 2020: “We cannot give up eating for fear of choking, we should treat gaokao dialectically. On the whole, its advantages far outweigh its disadvantages.”) One major reason was that numbers are incorruptible — the richest man in Sichuan might buy that Porsche, but he can’t buy his kid’s way into stomatology. And, despite their youth, many students were realists. A nonfiction student named Sarinstein— he created this name because he admired Sartre and Einstein — profiled a ten-year-old schoolboy. He observed how, in the classroom, the boy’s cohort had been seated, from front to back, according to their exam scores.

“Sarinstein wrote: China’s system cannot afford individualized education, caring for one’s all-around and healthy growth. . . . Our system is merely a machine helping the enormous and somewhat cumbersome Chinese society to function—to continuously supply sufficient human resources for the whole society. It is cruel. But it is also probably the fairest choice under China’s current circumstances. An unsatisfying compromise. I haven’t seen or come up with a better way.

They often used the term neijuan, or involution, a point at which intense competition produces diminishing returns. For them, this was unavoidable in a vast country. For one writing assignment, a freshman engineering student named Milo returned to a Chongqing auto-parts factory that he had first visited eight years earlier, for an elementary-school project. This time, when Milo interviewed the boss, he was struck by how old the man looked. The boss explained that booming business required frequent travel and many alcohol-fuelled banquets with clients. “I had no time to take care of my family,” he told Milo. “My kids do not understand me and even dislike me, since I seldom show up. What’s more, after drinking so much alcohol, I sometimes have a terrible stomachache.”

Cheating on the Gaokao Exam in China

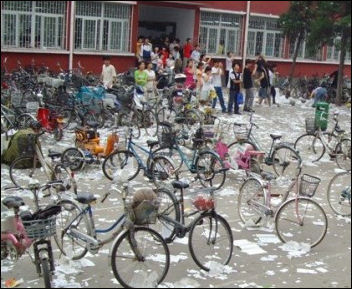

parents waiting Despite stiff penalties, stories of cheating on the gaokao surface every year, ranging from leaked exam papers to fake candidates. Spy cameras, radio devices and earpieces that transmit questions and receive answers have been found hidden in wallets, pens, glasses, jewellery, rulers and underwear. In all, 2,645 cheaters were caught in 2008. Three separate scams were uncovered at single school in Zhejiang province. In 2009 organized cheating was found in the college exam venues of northeast Jilin province, western Guizhou province, northern Shanxi province and central Hunan province.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “Each year, cheating scandals become the talk of China. One common tactic was for students to give their identification cards to look-alikes hired to take the test; later, many provinces installed fingerprint scanners at test centers. In 2008, three girls in Jiangsu Province were caught with mini-cameras inside their bras; their aim was to transmit images of the exam to people outside the classroom who would then provide answers. In 2012, the big scandal involved students in Huanggang, Hubei Province, famous in the past decade for churning out students with high scores; several dozen students were caught there using small monitors, costing nearly $2,500 that resembled erasers and that allowed the students to receive electronic messages with test answers. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times June 30, 2012]

According to the New York Times: Some parents hire companies to surreptitiously transmit answers to their children on exam day. Others bribe local officials to get a peek at the test before it is administered. Officials in many provinces have tried to crack down on cheating in recent years, going so far as to ban bras with a metal underwire, worried that they might hide transmission devices. In 2015, in the city of Luoyang, in central China, the authorities used drones to catch people using radios to broadcast answers. But the ranks of cheaters have only grown, and they have excelled at finding ways around the government’s restrictions, creating products like pens equipped with cameras and tank tops outfitted with audio receivers. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 7, 2016]

After the 2008 exam, eight parents and teachers were jailed on state secret charges after using hi-tech communication devices to help pupils cheat on the gaokao. Those involved used scanners and wireless earpieces to transmit exam answers. They were sentenced to between six months and three years for illegally obtaining state secrets. It is not revealed whether any students were punished. The Legal Daily newspaper said the parents began plotting in 2007 because their children's achievements were “not ideal”. One group bribed a teacher to fax them the test paper and paid university students to provide answers, which were transmitted to the children through earpieces. The ruse was discovered when police detected “abnormal radio signals” near the school. Another man had created an even more elaborate - and expensive - system. He bribed a student to send him the questions using a miniature scanner and hired nine teachers to answer them. He then sent their work back to his son and the other boy. A teacher was also jailed for charging parents to deliver answers to students. The equipment he used failed on the day. [Source: The Guardian, Tania Branigan, April 3, 2009]

In 2009, eight parents and teachers were jailed on state secret charges after using communication devices - including scanners and wireless earpieces - to help pupils cheat. In June 2011 several days the gaokao took place, AP reported: “China's Education Ministry says police have detained 62 people for selling wireless headphones, two-way radios and other electronic devices to cheat on this week's nationwide college entrance exam. The ministry said the detentions are intended to protect the exam's integrity.

According to the Wall Street Journal: In 2014, a student—who had driven a BMW to test site in Liaoning province—was caught by an official when he tried to cheat by looking at his phone. Once exposed, the student kicked the official and continued with his assault until security guards came and took him away. All the while, reports said, he was yelling about his father and how untouchable he is. This brought memories of 2008 when the son of a senior police officer in China coined a catchphrase for spoiled bratdom when he fled the scene of a fatal car crash, shouting, “My dad is Li Gang!” [Source: China Real Time blog, Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2014]

Using A Marathon to Cheat on the Gaokao

In 2010, several participants in the Xiamen marathon were busted for gaming race times by hiring faster runners to carry the microchips that record their times across the finish line. An investigation revealed that many of the cheaters were students from Shandong province hoping to qualify for extra-credit athletic points to boost their gaokao scores.

According to The Guardian: “In January 2010, thirty runners — almost a third of the runners who finished in the top 100 — were disqualified from a marathon in the southern port city of Xiamen for cheating. Some of them hired imposters to compete in their place. Some competitors jumped into vehicles part way through the route, Chinese media reported, while others gave their time-recording microchips to faster runners. Numbers 8,892 and 8,897 both recorded good times — but only thanks to number 8,900, who carried their sensors across the finish line.” [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 21, 2010]

Jiefang Daily, the Shanghai Communist party newspaper, said organizers caught the cheats when they scanned video footage. The paper said most of those involved had apologized, but that those showing an “uncooperative attitude” would be prevented them from competing in future events. There was more than just prestige at stake in the marathon. Competitors stood to gain a crucial advantage in China's highly competitive university entrance exams. Those who finished in under two hours and 34 minutes could add extra points to their score in the gaokao, helping to explain why several of those disqualified came from a middle school in Shandong province.”

Measures Take Against Cheating on the Gaokao

Test centers in Inner Mongolia use finger vein recognition (as opposed to fingerprint recognition) to verify test takers’ identities, according to the South China Morning Post. Metal detectors, facial recognition, and fingerprint recognition have been employed around the country. Candidates in Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces will have their faces scanned to ensure they match a submitted photo. [Source: South China Morning Post, June 6, 2018; Lucy Best, Sup China, June 7, 2018]

Concern about cheating is such that papers are kept under armed guard. In 2008 their classification was upgraded from “Secret” to “Top Secret”. Stephen Wong wrote in the Asia Times, “Chinese authorities have tried everything to prevent cheating. They installed closed-circuit television networks at exam venues, sent police to patrol exam rooms and made candidates of the national college entrance examinations sign an honesty declaration. However, as the Chinese say: “Good is strong, but evil is 10 times stronger”, and cheaters continue to develop more sophisticated techniques.”[Source: Stephen Wong Asia Times, August 22, 2009]

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian: Most examination rooms install CCTV cameras, and some use metal detectors. In 2015, police busted a syndicate in Jiangxi province, where professional exam-takers were charging parents up to a million yuan ($150,000) to pose as students. Iris-matching has been used to verify the identity of students. Exam papers are escorted to schools by security guards and monitored with GPS trackers, while the examiners who draft them are kept under close scrutiny in order to avoid leaks.[Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

Cheating on the gaokao carries a penalty of up to seven years in jail in accordance with a law enacted in November 2015. According to the New York Times it “states that people caught cheating or facilitating cheating on national exams could face up to three years in prison and a fine for minor cases, or up to seven years in prison for more serious cases. Those people would also be banned from taking national exams for three years. Legal experts said that the law would probably be used to go after leaders of cheating rings and that students might not be a primary target. Still, human rights experts said it was worrisome that China would threaten to impose severe penalties on teenagers for cheating. “If it is true that students found guilty of cheating end up receiving seven-year criminal sentences, this would be fairly disproportionate compared with the gravity of the ‘crime,’ ” William Nee, a China researcher at Amnesty International said.[Source: Javier C. Hernández, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 7, 2016]

“Officials said the law was necessary to preserve fairness in the exam. Many students and parents praised the effort to impose severe punishments on cheaters, saying it would serve as a powerful deterrent. But several were less certain of the law’s merits, saying it was too harsh. Wang Yiran, 19, a freshman at Yangtze University in central China, said the law might discourage students from reporting incidents of cheating because they feared sending another student to jail. “It’s simply too strict,” Ms. Wang said. “Because the punishment is so severe, no one will want to say anything.” Bella Hou, 19, a freshman at the Beijing Institute of Technology, said she thought imposing a severe penalty was the only way to stop students from cheating. “It’s really necessary to eliminate cheating on the gaokao,” she said. “Cheating affects everyone.”

“On Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, the reaction was mixed. One user wrote that a seven-year sentence was too harsh, saying, “That’s almost the same as the punishment for a hit and run.” Global Times, a nationalistic Chinese newspaper, described the law as important to upholding a sense of “social justice” in Chinese society, given the gaokao’s role as a path to economic mobility for poorer families. In June 2016, Chinese news media reported the details of the first case to be subject to the new law, which involved cheating on a postgraduate entrance examination in December. Officials said they had shut down 11 educational organizations in connection with the case. Officials did not announce penalties for those named in the investigation, including a former worker at a printing house that produced test materials.

Chinese Protest for Their Right to Cheat on the Gaokao

In June 2013, ahead of that year’s gaokao, an angry crowd of 2,000 parents and students descended on a high school in Hubei province to protest a new education policy that banned cheating. They smashed cars and chanted outside. According to the Telegraph’s report of the riot, one educator inside the school posted on a messaging service, “We are trapped in the exam hall. Students are smashing things and trying to break in.” At least one teacher was punched in the face. [Source: Lily Kuo, Yahoo, Finance, June 21, 2013]

According to Yahoo News: Metal detectors had been installed in schools to route out students carrying hearing or transmitting devices. More invigilators were hired to monitor the college entrance exam and patrol campus for people transmitting answers to students. Female students were patted down. In response, angry parents and students championed their right to cheat. Not cheating, they said, would put them at a disadvantage in a country where student cheating has become standard practice. “We want fairness. There is no fairness if you do not let us cheat,” they chanted.

“The day’s protests sparked a broader debate about entrenched corruption in Chinese society. On the social media site Sina Weibo, a Chinese broadcaster, the Voice of China commented “Cheating isn’t what’s wrong. What’s wrong is when cheating becomes the standard. When people stop being ashamed of breaking the rules, and cheating becomes the unspoken rule and abiding by law becomes an alternative. What this society lacks isn’t just rules; society is an exam hall. Dreams depend on fairness and rules.”

“Nepotism and elitism among high-level officials and business heads has also served as justification for cheating. One blogger said, “Why can the leadership’s children cheat but the common people can’t?” Another blogger wrote(registration required), “When committing evil becomes a habit, of course it should become a right.” The official stance appeared to soften following the protests. The local government said that “exam supervision had been too strict and some students did not take it well.”

Favoritism in the Gaokao

gaokao stress In March 2018, the Ministry of Education said it would scrap awarding bonus points to students who held talent certificates in sports, had won a middle school Olympian competition in mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology or information, and for those who had been awarded provincial level moral titles. [Source: South China Morning Post, June 6, 2018]

A gaokao-scoring scandal in northern Liaoning province in 2014 took advantage of exam-graders being allowed to award extra-credit points to national-level student athletes and promising young scientists. According to Bloomberg: These points, apparently, are sometimes for sale. Liaoning authorities uncovered a cheating ring in which local exam administrators invited parents of test-takers to pay sums ranging from 40,000 yuan ($6,480) to 80,000 yuan to inflate their son’s or daughter’s exam scores with extra points intended for athletes. At least 74 students have admitted to cheating under this scheme, according to a report published in the Henan Business News. [Source: Christina Larson, Bloomberg, July 8, 2014]

In 2018, two top education officials in Zhejiang province were fired and others were under investigation amid accusations that results of English language test were manipulated on the gaokao. Protesters complained of unfairness and questioned the scores. According to the South China Morning Post: The exam scandal began when results for the English gaokao exam were released, prompting many students and parents to question the grading method. Some students, who had fared well on objective test questions, such as multiple choice, lost more points on essay questions, leading to a wide-ranging public outcry and suggestions of under-the-table manipulation of grades. [Source: Phoebe Zhang, South China Morning Post, December 5, 2018]

In response, the Zhejiang education examination authority issued a statement but this further fuelled public anger. The authority said that after the tests were graded it had found some of the test questions were significantly harder than the previous year’s. To level the different tests, the committee decided to “curve” the points for some of the reading and essay questions. “I have been studying until midnight every day and worked so hard that I lost so much of my hair. I was happy with the English exam because I lost only a couple of points on the objective questions, but I only got 136 out of 150, while those who didn’t study got 135, or even 140. How am I supposed to feel?” a student wrote online.

Regional and Socioeconomic Unfairness of the Gaokao System

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian:“In China, the gaokao is sometimes described as a dumuqiao, which translates as “single-lo — a difficult path that everyone has to walk. But some have better shoes than others. Rich families lay on extra tutoring for their children in what Jiang Xueqin, a Canadian-Chinese education scholar, described as an “arms race” among households looking to increase their child’s chances. Provinces with larger populations have tougher standards of entry into the best universities, while those that are sparsely populated set a lower bar. (This loophole has led to illegal “gaokao migrants” transferring to schools in Inner Mongolia just before the exam.) Students in Beijing and — they are the beneficiaries of generous local — despite being more likely to be privileged anyway. “Scores are highly correlated with socioeconomic status,” Trey Menefee, a lecturer at the Hong Kong Institute of Education, told me. I asked if he considered the exam meritocratic. “I don’t,” he replied, “but almost every Chinese person does … Or it’s meritocratic only because it’s equally bad for everyone.”[Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

Dissatisfaction with regional gaokao unfairness is rising. According to the New York Times the test was intended to enhance social mobility and open up the universities to anyone who scored high enough. But critics say the system now has the opposite effect, reinforcing the divide between urban and rural students. The top universities in big cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing are the most likely to lead to jobs and the hardest to get into. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, June 11, 2016]

Students from less developed regions are vastly underrepresented at these colleges. That is because they attended schools with less money for good teachers or modern technology and because the admissions preference for local applicants means they often need higher scores on the gaokao than urban students. “It is a system that benefits the privileged at the expense of the disadvantaged,” Sida Liu, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, wrote in an email. “Without the improvement of schools in these regions, I would not expect any major change in educational inequality in China.”

“At issue is China’s state-run system of higher education, in which top schools are concentrated in big prosperous cities, mostly on the coast, and weaker, underfunded schools dominate the nation’s interior. The exam gives the admissions system a meritocratic sheen, but the government also reserves most spaces in universities for students in the same city or province, in effect making it harder for applicants from the hinterlands to get into the nation’s best schools.

Protests Over Efforts to Reform the Regional Unfairness of the Gaokao System

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: Chinese “authorities have sought to address the problem in recent years by admitting more students from underrepresented regions to the top colleges. Some provinces also award extra points on the test to students representing ethnic minorities. In the spring of 2016, the Ministry of Education announced that it would set aside a record 140,000 spaces — about 6.5 percent of spots in the top schools — for students from less developed provinces. But the ministry said it would force the schools to admit fewer local students to make room. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, June 11, 2016]

Not everyone is happy the decision. “Cheng Nan has spent years trying to ensure that her 16-year-old daughter gets into a college near their home in Nanjing, an affluent city in eastern China. She wakes her at 5:30 a.m. to study math and Chinese poetry and packs her schedule so tightly that she has only 20 days of summer vacation. So when officials announced a plan to admit more students from impoverished regions and fewer from Nanjing to local universities, Ms. Cheng was furious. She joined more than 1,000 parents to protest outside government offices, chanting slogans like “Fairness in education!” and demanding a meeting with the provincial governor. “Why should they eat from our bowls?” Ms. Cheng, 46, an art editor at a newspaper, said in an interview. “We are just as hard-working as other families.”

“Parents in at least two dozen Chinese cities have taken to the streets in recent weeks to denounce a government effort to expand access to higher education for students from less developed regions. The unusually fierce backlash is testing the Communist Party’s ability to manage class conflict, as well as the political acumen of its leader, Xi Jinping. The nation’s cutthroat university admissions process has long been a source of anxiety and acrimony. But the breadth and intensity of the demonstrations, many of them organized on social media, appear to have taken the authorities by surprise. In Wuhan, a major city in central China known for its good universities, parents surrounded government offices to demand more spots for local students. In Harbin, a northeastern city, parents marched through the streets, calling the new admissions mandate unjust.

“But in Luoyang, a city in Henan Province, one of China’s poorest and most populous, protesters countered that children should be treated with “equal love.” And in Baoding, a few hours’ drive southwest of Beijing, parents accused the government of coddling the urban elite at the expense of rural students. When they need water, land and crops, they come and take it,” said Lu Jian, 42, an electrician who participated in the protests in Baoding. “But they won’t let our kids study in Beijing.”

Taking the gaokao

Reforming the Gaokao

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian:“There has been talk of reforming the gaokao for as long as it has existed, but little ever comes of it. The major concession in the early 2000s was to allow separate provinces to draft their own exam papers. In 2016, top universities trialled interviews with students who show special promise at school. Those who impress may be awarded extra points, which are added to their final exam score. Many students and their families have also called for the English paper – a stumbling block for many without access to private tuition – to be made optional.[Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

Jiang Xueqin, deputy principal of the Peking University High School, wrote in The Diplomat: “Everyone’s in agreement: the national college entrance examination (gaokao) robs Chinese students of their curiosity, creativity, and childhood. So as gaokao students, with their thick textbooks and memory pills, sequester themselves in four-star hotels while their parents prowl the neighbourhood for construction noise and rambunctious restaurant patrons, now might be a good time to devise an alternative to the gaokao.” [Source: Jiang Xueqin The Diplomat. June 3, 2011]

On reforming the gaokao Jiang wrote: “First, this alternative must be an objective indicator of a student’s academic performance. College admissions committees or admission interviews would be unacceptable because it would offer too much power to individuals and institutions that can’t be trusted. No one would agree to a college lottery whereby qualified students are just randomly assigned a college. And artificial intelligence technology hasn’t yet advanced to the point where computers can replace college admissions officers. Thus, the only alternative seems to be a series of tests.”

“But even with tests we need to consider what we want to test. If we were to test writing and thinking ability, then that would mean an automatic bias towards the children of well-educated parents who have from an early age discuss books, current affairs, and travel plans with their child over the dinner table. Moreover, to teach thinking and writing (or any soft skills such as creativity and collaboration) would require highly specialised and highly professional teachers who would naturally congregate in expensive private schools or prestigious public schools in Beijing and Shanghai. And if this were the case, China would just be like the United States, where education is monopolised by the self-perpetuating and self-interested educated elite, and social mobility through education becomes a distant dream for everyone else.”

Resistance to Reforming

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian:“Meanwhile, relatively small changes can meet fierce resistance. In May, the government announced that a quota of 80,000 university places in Jiangsu and Hubei provinces would be reserved for students from poorer regions, in an effort to address provincial inequality. But mobs of middle-class parents took to the streets in six cities to protest against the measures, fearful that positive discrimination in favour of poorer families meant their own children would lose out. “The gaokao isn’t for everyone,” Jiang Xueqin told me. “It’s for the middle class.” [Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

“When it comes to more comprehensive reform, the general consensus among education scholars in China is that any alternative would be too easily manipulated by the rich. Were coursework or regular school marks to be taken into account alongside exam grades, bribery would be even more rampant than it already is (parents often give “red packages” stuffed with banknotes to teachers in return for special attention for their child in class, or simply a seat nearer the front). The same goes for direct university admission. And so, futures are still decided by how well each child performs at a cramped desk in a closed room for two days in early June.

Jiang wrote: China has 800 million peasants who depend on schooling as their child’s only chance out of the rice fields. Rural children don’t have access to the libraries, well-trained teachers, and intellectual spaces that wealthy cities can offer — all they have is their willingness to work hard to improve themselves. If Chinese believe in fairness and social mobility, then tests must be more about the student’s ability to memorise the textbooks he has access to, rather than about his ability to think critically, which is the result of making the most of a special set of resources available only to society’s elite.” [Source: Jiang Xueqin The Diplomat. June 3, 2011]

“So, if we were to start from scratch and try to build an alternative to the gaokao, we would end up with as the only viable alternative — the gaokao. That’s what a lot of people tend to forget: that given the complete lack of trust in each other and in institutions, given the stifling poverty that most Chinese find themselves in, and given China’s endemic corruption and inequality, the gaokao, for better or worse, is the fairest and most humane way to distribute China’s scare education resources.”

“Yes, the images of children memorising and regurgitating away for 18 years may be disheartening. The poor eyesight, bad posture, and crushing of imagination, independence, and initiative will haunt them for the rest of their lives. But we must remember that many of these children and their families find themselves fortunate just to be able to dream of a better life.”

Image Sources: China Smacks, Shanghaiist, China Daily, Wall Street Journal, Xinhua, Photobucket

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022