CARTWHEELING SNAKE OF SOUTHEAST ASIA

In April 2013, scientists in Malaysia said in a study published in the journal Biotropica that they had discovered a snake that intentionally does cartwheels, likey as a way to escape potential predators. The snake — the dwarf reed snake (Pseudorabdion longiceps) — is a small, non-venomous, black to reddish snake found widely through parts of Southeast Asia. Though it is common it is rarely seen by humans because of its semi-burrowing and nocturnal lifestyle and fact that during the day, it’s usually hiding under rocks or leaf litter. The trait may be common among other, similar species. [Source:Ed Cara, Gizmodo, April 5, 2023]

Ed Cara wrote in Gizmodo: A few years ago, study author Evan Seng Huat Quah spotted a dwarf reed snake actively launching itself into the air and rolling away in a coil-like fashion — a cartwheel, in other words. Quah, a herpetologist at the University of Malaysia of Sabah, wasn’t the first person to ever report seeing a cartwheeling snake. Unfortunately, like others before him, he didn’t have any way to record the behavior at the time, meaning the sighting was purely anecdotal. But luck would eventually shine upon him and his colleagues in August 2019, while they were on an unrelated research trip to the mountains of Kedah, Malaysia.

“We were thrilled when we came across the specimen we recorded in this instance, when we were conducting herpetological surveys for other species at the site,” Quah told Gizmodo in an email. “This time, we had our camera gear in hand and were able to take the images used in this publication.”

The snake was startled by the scientists and tried to quickly cartwheel away from them down a hilly road. But they were then able to capture the animal and place it on a flat surface, where it again cartwheeled several times in full view of their cameras. The team published their findings on Wednesday They also cite a YouTube video of another dwarf reed snake cartwheeling that was uploaded last year.

Rolling as a form of movement has rarely been seen among other land-dwelling animals. No animal that does roll seems to use it as a primary means of locomotion, the scientists note, and these animals usually deploy passive rolling, where they use external forces, like the wind or gravity, to do the heavy lifting. So the dwarf reed snake’s willingness to fling itself is unusual even among rollers.

The snakes likely only cartwheel to escape or confuse potential predators, Quah explained, since they slither just like any other snake when traveling through leaf litter or foraging for food. But they might not be the only cartwheeling reptile in town; there have been other anecdotal sightings of different snake species, including that of a closely related member belonging to the same genus. “We believe that this behavior has long gone unnoticed due to the secretive nature of these snakes. These snakes are small in size and semi-fossorial, meaning they usually hide in the leaf litter or burrow into debris. This helps them remain undetected,” Quah said.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SNAKES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, LARGEST, SENSES, FEEDING, BREEDING factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES: VENOM, PHYSIOLOGY, DEADLIEST SPECIES factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKE BITES: ANTIVENOMS, WHAT TO DO AND NOT DO factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN ASIA: KRAITS AND RUSSELL'S, SAW-SCALED AND PIT VIPERS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM, BITES, TREATMENTS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS IN ASIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM factsanddetails.com

INDIAN COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITES factsanddetails.com

KING COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS AND HUMANS: FESTIVALS, SNAKE CHARMERS, ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HUNTING, PREY factsanddetails.com

INDIAN PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BURMESE PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, BEHAVIOR, PREY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

RETICULATED PYTHON: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SIZE, PREY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS AND HUMANS: HUNTERS, PETS, AND FLORIDA INVASIONS factsanddetails.com

PYTHON ATTACKS ON HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Flying Snakes of South and Southeast Asia

Three species of snakes in the genus Chrysopelea are known to glide, and one, the paradise tree snake has even been seen turning in mid-air. Genus Chrysopelea: Species: 1) Golden Flying Snake (Chrysopelea ornata); 2) Paradise Tree Snake, Paradise Flying Snake (Chrysopelea paradisi); 3) Twin-barred Tree Snake, Banded Flying Snake (Chrysopelea pelias); 4) Moluccan Flying Snake (Chrysopelea rhodopleuron); 5) Indian Flying Snake (Chrysopelea taprobanica)

Borneo is arguably the best place to see flying snake. These creatures were long regarded as fantasies created by explorers that had been in the jungle too long. The paradise tree snake (paradise flying snake, Chrysopelea paradisi) of Borneo can glide from tree to tree through the upper canopy of the rain forest. It is shaped like a ribbon and has blue, green scales with flecks of red and gold. The snakes are believed to have developed their ability to fly to escape from predators but they may also their extraordinary talent to surprise prey. [Source: Tim Laman, National Geographic, October 2000]

Paradise tree snakes are very common in some places in Borneo. They feed on lizards, frogs and bats. They ‘fly’ by climbing to the end of a branch and then thrusting themselves towards their destination. Whilst in flight it maintains a concave shape to aid the gliding whilst also undulating its body. ‘Flying’ between trees uses less energy than climbing down trees to the ground, moving on the ground and climbing back up trees. Describing it, Tim Laman wrote in National Geographic, “The snake moved along the tree branch...Suddenly it dropped over the edge, just holding on by its tail, and then pushed off into the damp air. It changed shape as it began to drop, ribs spreading and body flattening as it swam through the air.” Flying snakes are also adept tree climbers. They can climb vertically at great speeds, David Attenborough wrote, by “gripping the bark using the edge of a “broad traverse scales beneath the body and bracing itself by the coils sideways against any roughness in the bark.”

Around 450 B.C., the ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote about winged serpents in Arabia. He described them as small, water-snake-like creatures with wing membranes similar to bat wings. Herodotus did not see them himself; he said he heard about them in Arabia and saw bones and spines of them. He said the serpents had variegated markings and were pests but their population remained small due to their reproductive life and the fact that when flew east from the desert toward Egypt in the spring, they were eaten by ibises. [Source: Google A1]

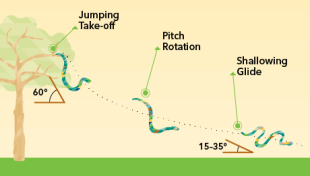

How the Flying Snakes in Borneo Fly

Flying snakes push off from tree branches while rotating their ribs to flatten their bodies, making side-to-side movements as they glide. Describing a flying Borneo snake, David Attenborough wrote, "Once up in the tree it moves from one form on a branch to another by racing along a branch and launching itself off. In the air, it flattens its body so instead of being round, it is broad and ribbon like. At the same time, it draws its length into a series of S-shaped coils...When it takes off in the air, it pulls up its abdomen towards its spine so that its underside becomes concave, and bends its log body into zigzags so that it forms a squarish rectangle that is surprisingly effective in catching the air...It even seems able, by writhing, to bank and change course in mid-air so that, to some degree at least, it can determine where it will land.”

Jake Socha, a biomechanics professor at Virginia Tech, has studied the paradise tree snakes in captivity and in ts natural habitat. Ones that are nudged off a perch dangle like a “J” and fling themselves upwards and away. After plunging less than 10 feet is takes on a S-shape and begins undulating in a similar fashion to the way its crawls on the ground, only more slowly and more laterally. The snakes descend at an angle as slight as 13 percent. A snake launched from 20 feet in the air can traverse a distance of 69 feet

When the paradise tree snake is on a tree or the ground its body is round like other snakes. It achieves it ribbon-like concave shaped by flaring out the ribs so that it nearly doubles it width. The flattening effect turns the snake into an airfoil and effectively doubles its underside to create a makeshift wing that is more aerodynamic than that of many birds. The S-shaped adopted by the snakes when they are in flight is similar aerodynamically to planes with slotted wings (wings with periodic gaps that give it more lift at low speeds).

Studying Flying Snake Gliding

Socha and Lorena Barba, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering in the George Washington University School of Engineering and Applied Science, have studied how snakes fly (glide) using a experiments in their habitat and computer modelingwith graphic processing units (GPUs) and computational fluid dynamics. [Source: Lauren Ingeno, George Washington University, March 5, 2014]

Socha, has been studying and filming the movement of flying snakes for years, by launching them from cranes in their natural habitats. To begin to understand the aerodynamic characteristics of the snake body profile, his team built physical models made of tubing and tested them in a wind tunnel to measure the lift force of the flight. These experiments revealed something unusual. Researchers expected the aerodynamic lift of the snake to increase with the angle of attack (the angle between the profile and the trajectory of flight) and then to drop suddenly after a stall. But Dr. Socha measured lift increasing up to an angle of 30 degrees, a sharp boost at an angle of 35 degrees, then a gentle decrease. This suggests that flying snakes use a mechanism called lift enhancement to get an extra boost, explained Dr. Barba.

While the experimental study revealed a phenomenon—that snakes’ bodies create a lot of lift—a computer simulation could better explain how this phenomenon occurs. “With simulation, you can really see the fine details of what is happening in the air as it moves around the object,” Dr. Barba said. “We decided it would be revealing to use this tool to find out, first of all, if we could observe the same feature of lift, and if so, if we would we be able to interrogate the flow by getting detailed quantities and visualizing it.” So Dr. Barba and her team—which included Mr. Krishnan, Dr. Socha and Pavlos Vlachos of Virginia Tech—successfully modeled a 2D cross-section of the snake body using GPU-accelerated computational fluid dynamics simulations. And lo and behold, the team observed the same lift enhancement mechanism, recreating with simulation what had happened in Dr. Socha’s previous experimental study.

Computer modeling acts as a “virtual microscope” for fluid mechanics, Dr. Barba said, and so the simulations enabled the researchers to zoom in very close to the body in order to understand how the air swirls around the snake. They saw that at certain angles of gliding, a snake’s curves can generate extra boosts of power. At this angle, small vortices, or whirlwinds, of air generated around the snake give it added suction.

Tentacled Snakes and Their Unique Hunting Method

Tentacled snakes (Erpeton tentaculatum) are also known as tentacle snake. Native to Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam in Southeast Asia, they are rear-fanged aquatic snakes that have tentacles on their nose that may help them find prey in muddy water. They are relatively small snakes, averaging about 50 to 90 centimeters (20 to 35 inches) and come in two color phases, striped or blotched, with both phases ranging from dark gray or brown to a light tan. [Source: Wikipedia]

The two tentacles on the snout of the tentacled snake is unique among snakes. The twin "tentacles" on the front have been shown to have mechanosensory function and help it catch fish — its main prey and food. Although it does have venomous fangs, the tentacled snake is not considered dangerous to humans. The fangs are small, only partially grooved, and positioned deep in the rear of the mouth. The venom is specific to the fish that the tentacled snake eats.[

Tentacled snakes live their entire lives in the murky water of lakes, rice paddies, and slow moving streams, and can be found in fresh, brackish, and sea water. A good example of its habitat is the Tonlé Sap lake in central Cambodia, which contains a lot silt and has a large fish population.

Tentacled snakes can stay underwater for up to 30 minutes without coming up for air. They move awkwardly on land. In dry times and at night, they may burrow itself in the mud. Tentacled snakes have a unique ambush method of hunting. Much of the time tentacled snakes assume a rigid posture, with their tail anchored while their body assumes a distinctive upside-down "J" shape. The snake will keep this shape even when grabbed or moved by a person, an apparent freeze response. The striking range is a narrow area downwards from its head, somewhat towards its body. Once a fish swims within that area the snake will strike by pulling itself down in one quick motion towards the prey.

High-speed cameras and hydrophones have revealed the snake's method of ambush in greater detail. The snake anticipates the movements of the fish as it attempts to escape. As the fish swims into range, the snake creates a disturbance in the water by moving part of its body posterior to the neck. This disturbance triggers an escape reflex in the fish called the C-start, in which the fish contorts its body into a "C" shape. Normally at this point the fish would swim quickly away from the disturbance by quickly straightening its body, but the snake grabs it, usually by the head, anticipating its movement. The snake catches fish by tricking them into reflexively attempting to escape in the wrong direction. Unlike most predators, the snake doesn't aim for the fish's initial position and then adjust its direction as the fish moves, it heads directly for the location where it expects the fish's head to be. The ability to predict the position of its prey appears to be innate. The tentacled snake retracts its eyes when it begins to strike.

Elephant Trunk Snakes

Elephant trunk snakes (Acrochordus javanicus) are also called Javan file snakes. Found in southern Thailand, the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Borneo (Kalimantan, Sarawak) and a number of Indonesian islands including Java, Sumatra, and possibly Bali), they comprise a species of snake in the family Acrochordidae — a group of primitive non-venomous aquatic snakes. [Source: Wikipedia]

Elephant trunk snakes have a wide and flat head that looks sort of like the trunk of an elephant, hence their name. The nostrils are situated on the top of the snout and they also look a little like. boas but their head is only as wide as their body. Females are bigger than males, and they reach 2.4 meters (94 inches) in length. Their back side is brown while their bottom side is pale yellow. Their skin is baggy and loose giving the impression that it is too big for the animal. The skin is covered with small rough adjacent scales and valued in the leather industry.

Elephant trunk snakes live in coastal habitats such as rivers, estuaries and lagoons and prefer freshwater and brackish environments to saltwater ones. They are nocturnal and rarely come on land. They can stay under water for up to 40 minutes. They are so adapted to life underwater their body cannot support their weight out of water and staying out of the water too long can cause serious injury. Elephant trunk snakes are ambush predators that prey on fish and amphibians. They usually catch prey by folding their body firmly around the prey. Their loose, baggy skin and its sharp scales prevent prey from escaping and is particularly effective against fish that cover their bodies with viscous, protective mucus.

In Southeast Asia, one small snake aquatic feeds on mudskippers and small crabs. They can close their nostrils underwater and have a venom particularly good at killing their prey. They also have a special valve on their throats that closes when they underwater and allow the snake to open is mouth for hunting without taking in water.

Snakes That Insert Their Heads into Living Frogs' Bodies to Swallow Their Organs

Mindy Weisberger wrote in Live Science: For knife-toothed kukri snakes, the tastiest parts of a frog are its organs, preferably sliced out of the body cavity and eaten while the frog is still alive. After observing this grisly habit for the first time in Thailand, scientists have spotted two more kukri snake species that feast on the organs of living frogs and toads. The new (and gory) observations suggested that this behavior is more widespread in this snake group than expected. Two snakes also eventually swallowed their prey whole, raising new questions about why they would extract the living animals' organs first. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science: February 26, 2021]

The scientists documented a Taiwanese kukri snake (Oligodon formosanus) and an ocellated kukri snake (Oligodon ocellatus) pursuing amphibian organ meals, tearing open frogs' and toads' abdomens and burying their heads inside, according to the studies. O. formosanus would even perform "death rolls" while clutching its prey, perhaps to shake the organs loose. As the snakes swallowed the organs one by one, the amphibians were still alive. Sometimes, the process would take hours, the researchers reported.

There are 83 species of kukri snakes in the Oligodon genus in Asia. The snakes typically measure no more than 3 feet (100 centimeters) long, and the group's name comes from the kukri, a curved machete from Nepal, as its shape is reminiscent of the snakes' large, highly modified rear teeth. Kukri snakes use these teeth for slicing into eggs, but they can also be formidable slashing weapons (as some very unfortunate frogs have discovered).

In one study, published February 15 2023 in the journal Herpetozoa, scientists described three snake attacks on rotund banded bullfrogs (Kaloula pulchra), which are so round that they are also known as bubble frogs or chubby frogs. They have brown backs with lighter stripes down their sides and cream-colored stomachs, and they measure up to 3 inches (8 cm) long, according to Thai National Parks.

Two of the attacks were by Taiwanese kukri snakes, and took place in Hong Kong in October 2020. One snake, filmed on Oct. 2 in a residential neighborhood garden, emerged from a hole in the ground to bite a passing bubble frog, slicing open the frog and stuffing its head inside. Snake and frog tussled for about 40 minutes; the snake performed about 15 body rotations, or "death rolls," during the battle, according to the study. "We believe that the purpose of these death rolls was to tear out organs to be subsequently swallowed," Henrik Bringsøe, lead author of both studies and an amateur herpetologist and naturalist, said in a statement.

A second Taiwanese kukri snake was discovered on Oct. 8 in an urban park while "energetically" dining on a frog's organs that were "exposed and visible," the study authors wrote. The third attack on a bubble frog was by a small-banded kukri snake — the species that was first documented exhibiting this behavior — on Sept. 15, at a factory site outside a small village in northeastern Thailand. During the struggle, the snake performed 11 death rolls, its teeth buried firmly in the frog's belly. "The snake’s efforts resulted in its teeth penetrating the abdomen to such an extent that blood and possibly some organ tissue appeared," the scientists reported. "Eventually, the frog was swallowed whole while still alive."

Another study, published on the same day in Herpetozoa, presented an observation of an ocellated kukri snake feasting on an Asian common toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) inside a lodge in a national park in southern Vietnam. These toads are stout, thick-skinned and variably colored, and they measure about 3 inches (8.5 cm) long, according to Animal Diversity Web, a biodiversity database maintained by the University of Michigan's Museum of Zoology. Observers recorded this attack on May 31, 2020. The toad was already dead at the time, "and the snake was moving its head and neck side to side as if trying to work its way inside," the study authors wrote. Minutes later, the snake gulped down the toad whole.

In the 2020 study about small-banded kukri snakes eviscerating Asian common toads, the scientists hypothesized that the snakes selectively ate the organs to avoid the toads' deadly toxins. However, the ocellated kukri snake swallowed the toad after its organ appetizer, hinting that the snakes might have some natural resistance to the toads' poison. Chubby frogs also have a built-in deterrent that may encourage predators to go straight for their organs. While the frogs aren't toxic, they defensively secrete a sticky mucous that has an unpleasant taste, according to the University of California, Berkeley's AmphibiaWeb.

Demand for Snakes in Asia Rises in the Chinese Year of the Snake

Natalie Heng wrote in The Star, “In demand: Snakes with unique colours and skin patterns, such as those of the corn snake, are popular among pet owners. But this hobby is said to be driving an illegal trade in wild-caught snakes. In demand: Snakes with unique colours and skin patterns, such as those of the corn snake, are popular among pet owners. But this hobby is said to be driving an illegal trade in wild-caught snakes. [Source: Natalie Heng, The Star, January 29, 2013]

As Chinese New Year dawns, consumers are caught up in a frenzy of owning all things snake — with dire consequences. With the Year of the Snake drawing near, some animal lovers are seeking out snakes as pets, just like how rabbits were popular in 2011, the Year of the Rabbit. Even without being churned through the Chinese New Year branding machinery however, snakes are already in demand for their meat, in traditional medicine, and in high-end fashion.

In January, over 47,350 pieces of cobra bile and 1,680 cobra eggs were seized at Jakarta’s Soekarno-Hatta International Airport. In November, a report estimated that half a million python skins are exported from South-East Asia annually, in a trade worth $1 billion. “There is a higher demand for snakes right now, probably more than there has ever been,” says Chris Shepherd, deputy director of wildlife trade monitoring network Traffic South-East Asia. “The global reptile trade right now, for pets, is huge, and the trade in skins is really huge.”

Snakes and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Chinese snake dish

Natalie Heng wrote in The Star, “Scientists admit that few studies have attempted, or been able to determine, the scale of the illegal trade in snakes, and the effects of illegal harvest. What we do know is that there are hundreds of species of reptiles and amphibians harvested from the wild every year for trade. From the few studies that have been done, it looks like there is good reason for consumers to be cautious. The green tree python (Morelia viridis) is a popular snake in the global pet trade. It is one of Indonesia’s top exports, and stocks are declared as captive breds.

In 2011, however, scientists Jessica Lyons and Daniel Natusch from the University of New South Wales found that at least 80 percent of Indonesia’s green tree python exports were poached from the wild. This find highlights two important points: the potential for widespread fraud in the reptile export market and the difficulties pet owners face in differentiating between wild-caught and captive-bred stock. [Source: Natalie Heng, The Star, January 29, 2013]

There are many responsible snake owners who genuinely care for their pets and think that their hobby is harmless to populations in the wild. After all, snakes like the green tree python are not classified as a “threatened” species. Unfortunately, simply looking at an animal’s global conservation status does not reflect the damaging impact that harvesting might have on local wild populations. For example, the green tree python is listed as of “least concern” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List but the assessment is based on global distributions. In Indonesia’s Papua province and Maluku Islands, the researchers say traders have reported a decline in snake numbers, which indicates over-harvesting on a local scale.

Last year, both scientists conducted another survey in the same area but discovered that efforts to find out the long-term impacts of the pet trade on local populations were hampered by poor understanding of the biology and trade of the snake species, and the fact that they inhabit remote provinces. They found a great need for increased monitoring and enforcement to curb illegal trading activities. Aside from improving our knowledge of the species being traded, there is also a need to educate consumers. Pet owners need to be aware of the effects their demand for exotic wildlife can have on species and their habitats, as well as the illegal means used to supply animals for the trade, such as wild-caught animals being passed off as captive breds.

snake blood dish

According to the Wildlife and National Parks Department (Perhilitan), nine species of snakes are traded locally – the reticulated python, Burmese python, blood python, Borneo short-tailed python, ball python (or royal python), Oriental rat snake, king cobra, monocled cobra and equatorial spitting cobra. Perhilitan said 406 live snakes, 297,956 pieces of skin, 12,508 kg of meat, and 82 snake-based products were exported from Malaysia in 2011. Eight Malaysian snake species listed were in CITES Appendix II and so, subjected to controlled trade.

The local trade in snakes will soon be affected by an amendment to the Pet Shop Regulations 2012 under the Wildlife Conservation Act 2010. Perhilitan says not all local species will be allowed for trade under the regulation, citing this as a way to control the possession of harmful and dangerous snakes. Currently, the Act lists 169 species as “protected” (permit is required for any trade) and 14 as “totally protected” (no trade allowed).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; flying snakes from George Washington University

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, CNN, BBC, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025