SNAKES

Ball python

Snakes are scaled reptiles classified in the Order Squamata, which also includes their close relatives the lizards. There are over 3,000 species of snake, ranging in size from pencil-size African thread snakes to 25-foot anacondas large enough to swallow a human child. They live in almost every ecological niche, except the polar regions, and are particularly plentiful in tropical regions and deserts. [Source: Adrian Forsyth, Smithsonian, February 1988; Frederick Golden, Time magazine, October 13, 1997; Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, June 21, 2012]

Snakes are vertebrates. Among reptiles, snakes are most closely related to monitor lizards and Gila monsters. All these creatures have forked tongues and sense organs on the roofs of their mouth.

Colubrids, sometimes referred to as typical snakes, are the largest snake family, accounting for almost two thirds of all species. Common features among colubrids include a lack of a left lung, and backlimb girdel. Garter snakes, grass snakes, whip snakes and all rear-fanged venomous snakes are Colubrids. Colubrids are regarded as more developed than primitive blind snakes, thread snakes, and boas and pythons. Most dangerous venomous snakes are not Colubrids. They are front-fanged snakes.

Some snakes are easily killed by prolonged shelter to the sun that is why they often seek shade in the middle of the day. In temperate climates many snakes hibernate for three or four months in the winter: they don’t eat that entire time yet emerge at about the same weight as when they started. In some places some species gather in large numbers and live in the same den, which they return to year after year.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SNAKE BEHAVIOR: MOVEMENT, FEEDING, BREEDING factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

UNUSUAL SNAKES IN ASIA: FLYING, CARTWHEELING AND TENTACLED ONES factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES: VENOM, PHYSIOLOGY, DEADLIEST SPECIES factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKE BITES: ANTIVENOMS, WHAT TO DO AND NOT DO factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN ASIA: KRAITS AND RUSSELL'S, SAW-SCALED AND PIT VIPERS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM, BITES, TREATMENTS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS IN ASIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM factsanddetails.com

INDIAN COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITES factsanddetails.com

KING COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS AND HUMANS: FESTIVALS, SNAKE CHARMERS, ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN AUSTRALIA: VENOM, SPECIES, BITES, AVOIDANCE, TREATMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com

TAIPANS (WORLD'S DEADLIEST SNAKES): SPECIES, VENOM, BITES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIGER SNAKES: CHARACTERISTICS, REGIONAL MORPHS, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BROWN SNAKES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HUNTING, PREY factsanddetails.com

INDIAN PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BURMESE PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, BEHAVIOR, PREY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

RETICULATED PYTHON: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SIZE, PREY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS AND HUMANS: HUNTERS, PETS, AND FLORIDA INVASIONS factsanddetails.com

PYTHON ATTACKS ON HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Snakes: Snake World snakesworld.info ; National Geographic snake pictures National Geographic ; Snake Species List snaketracks.com ; Herpetology Database artedi.nrm.se/nrmherps ; Big Snakes reptileknowledge.com ; Snake Taxonomy at Life is Short but Snakes are Long snakesarelong.blogspot.com; Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Snake History

russell's viper

Herpetologists believe snakes developed from a group of lizardlike creatures that took up a burrowing lifestyle. Living in loose soil or leaf litter, these animals gave up their legs for a slithering style of locomotion, using the movable scales on their stomach as anchors for pulling themselves along the substrate. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, June 21, 2012]

Snakes most likely evolved about 90 million years ago from lizards that took to living underground or in forest litter and lost the use of their legs. Evidence of this includes the snake's lack of an eardrum (underground animals generally have no use for hearing) and the remnant of leg and pelvic bones still found in many snakes. Pythons, for example, have tiny leg bones which may be visible as minuscule claws at the base of their tails.

But the matter of how snakes evolved is far from settled. For some time there has been a debate on whether the first snakes evolved on land or in the sea. Some think they evolved from monsaurs, an extinct group of large marine reptiles. Even if this case it clear from anatomical evidence that modern aquatic snakes descended from terrestrial snakes.

In April 2006, scientists, announced the discovery of the oldest known snake in Patagonia. Measuring less than a meter in length and given the name Najash rionegrina, the fossil back up the case that snakes evolved on land. The skeleton contains a bone structure that support the pelvis, a feature lost by sea creature long before, two small rear legs and anatomical features suggesting that it lived in burrows. The deposits in which it was found also indicate it came from a terrestrial environment. The creature likely moved around like a snake. The purpose of the two legs is unknown.

In February 2009, Jonathan Block, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Florida, announced the discovery of a fossil of the most enormous snake ever found: a giant boalike snake that lived 60 million years ago that was as long as a bus and large enough to eat crocodiles and 150-kilogram giant turtles. Based on the size of it vertebrae the creature weighed between 730 kilograms and two tons and measures between 11 and 15 meters and was more than 1.25 meters wide at is widest point. The fossil was found in one of the world’s largest open cast coal mine in Cerrejon, Columbia. It was named Titanoboa, more or less meaning gigantic snake (See Below). Block told AFP, “Truly enormous snakes really spark people’s imagination but reality has exceeded the fantasies of Hollywood. The snake that tried to eat Jennifer Lopez in the movie “Anaconda” is not as big as the one we found.

Biggest, Longest and Smallest Snakes

According to Britannica, the smallest identified snake in the world is the Barbados thread snake, which reaches a length of 10.4 centimeters (4.1 inches). The reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) of Southeast Asia is the longest snake in the world, according to the Natural History Museum. On average, it reaches 6.25 meters, (20.5 feet) and weighs around 158 kilograms (350 pounds). One measuring 6.95 meters (22.8 feet) is the longest, reliably-measured wild reticulated python. Larger sizes have been reported, some claims reach up to over 10 meters (33 feet) in length, but these are considered controversial or unreliable. A captive reticulated python named "Medusa" was reported to measure 7.67 meters (25.2 feet) and weighed 158.8 kilograms (350 pounds).

The longest snake ever recorded was a 10-meter (32-foot, 9-inch) python — longer than the height of a giraffe — killed on the island of Celebes (Sulawesi, Indonesia) in 1912. In 2008, a seven meter reticulated python named Fluffy, kept at the Columbus, Ohio zoo, was said to be the largest snake in captivity. The python was as thick as a telephone pole. According to Wikipedia at the time of her death in 1999, a Burmese python named "Baby" was the heaviest snake recorded in the world at the time. She weighed at 182.8 kilograms (403 pounds) and was 5.74 meters (18 feet 10 inches) in length.

snake scales

The green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) is generally considered the most massive extant snake. One measuring 5.21 meters (17.1 feet) was the longest individual out of more than 780 anacondas measured around a cattle ranch by Jesús Antonio Rivas. There are reports of exceptionally large anacondas, some claimed up to 9 to 11 meters (30 to 36 feet), but these are controversial. Rivas cast doubt on the existence of exceptionally large anacondas due to factors such as constraints on body size and breeding ability. However, they suggested that sizes larger than those observed in the study area may be possible in habitats with permanent water bodies and little human intervention. In 2024, a large anaconda was found dead in Bonito, Brazil, which was initially measured around 6.45 meters (21.2 feet) by a rope and later reportedly measured more precisely at 6.32 meters (20.7 feet). The heaviest snake ever recorded, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, was an anaconda killed in Brazil that was 8.38 meters (27 feet, 6 inches), with a girth of 1.12 meters (44 inches) and weighed over 227 kilograms (500 pounds). Generally, green anacondas reach lengths of six to nine meters (20 to 30 feet), according to National Geographic. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

Biggest Snakes Ever

The biggest snake ever by one reckoning was the Titanoboa, which lived during the Paleocene Epoch (66 million to 56 million years ago) and is considered "the largest known member of the suborder Serpentes," according to Britannica. Adult Titanoboa are estimated to have been 13 meters, (42.7 feet) in length and weighed approximately 1,135 kilograms (1.25 tons). The Titanoboa was the largest predator on Earth following the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago and until the first appearance of the Megalodon around 23 million years ago, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History. Titanoboa cerrejonensis, the biggest Titanoboa, lived around 60 million years ago and was unearthed in 2002 in northeastern Colombia.

Extinct snakes are often known from fragmentary remains, so length estimates must be extrapolated using living species or more complete relatives. However, due to the large number of variables, these estimates can vary substantially between methods and should be treated with caution. Due to the lack of complete remains, the morphology of the extinct snakes is uncertain. P. colossus has been restored here with a small paddle at the end of the tail, a feature common in marine snakes. However, due to lack of remains this feature is speculative. Skull material is uncommon for fossil snakes. The heads of Gigantophis and Vasuki are inspired by a composite skull diagrams of Madtsoiidae snakes, Wonambi and Yurlunggur. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

Gigantophis garstini is a large member of the extinct snake family Madtsoiidae. Gigantophis is known from numerous vertebrae. In 2004, it was estimated between more than 9.3 and 10.7 meters (31 and 35 feet) in length by Jason Head & P. David Polly using regression analysis (10 meters (33 feet) shown here). A later study by Jonathan P. Rio & Philip D. Mannion used a regression analysis that compared the vertebral postzygapophyseal width to the total length in extant boine snakes. This regression estimated the largest vertebra of the Gigantophis type specimen at more than 6.9 meters (23 feet) (+/- 0.3 m). However, the authors urged caution due to uncertainties regarding the possible position of the vertebra in the spinal column, the lack of articulated madtsoiid remains, and the possibility that Gigantophis and extant boine snakes differ in the relationship between postzygapophyseal width and total length.

Palaeophis colossus is an extinct species of marine snake in the family Palaeophiidae. One vertebra, CNRST-SUNY 290, produced a length estimate of 8.1 meters (27 feet), comparing the trans-prezygapophyseal width to a variety of extant snake species. Using a different vertebral landmark of another vertebra, the the cotylar width of NHMUK PV R 9870, produced a length estimate of 12.3 meters (40 feet).

Titanoboa cerrejonensis is an extinct boid only known from large vertebrae and skull material, but size estimates suggest it is one of the largest snakes known. In 2009, Jason Head and colleagues estimated it at more than 12.8 meters (42 feet) (+/-2.18 m) by regression analysis that compared vertebral width against body lengths for extant boine snakes. In a later conference abstract, Head et al. estimated a length of more than 14.3 meters (47 feet) (+/-1.28 m) based on skull material and comparisons to anacondas.

Vasuki indicus is a large Madtsoiidae snake known from several large vertebrae. Datta & Bajpai applied two existing length estimation regressions on these vertebrae, producing estimates ranging from 10.9 and 12.2 meters (36 and 40 feet) and 14.5 and 15.2 meters (48 and 50 feet) (11.5 and 14.8 meters (38 and 49 feet) shown here). However, due to the incompleteness of the remains and limited knowledge of Madtsoiidae snake vertebral columns, Datta & Bajpai urged caution with the estimates.

A size comparison of various snakes living and extinct based on the best possible estimates (Human scaled to 180 cm (5 ft 11 in); The snakes are described above

New Contender for the Biggest Snakes Ever

In April 18, 2024 edition of the journal Scientific Reports, scientists in India announced that they had discovered the fossilized remains of a 47-million-year-old snake that appears to the largest known snake ever live. The massive snake — named Vasuki Indicus, with genus name taken from the mythical king of serpents in Hinduism and is associated with Shiva — measured 15 meters (50 feet) long, making it two meters (6.5 feet) longer than Titanoboa. Jacklin Kwan wrote in Live Science: A total of 27 fossilized vertebrae from the enormous snake were unearthed at the Panandhro Lignite Mine in Gujarat state. The Indian scientists think the fossils came from a fully grown adult. The team estimated the serpent's total body length using the width of the snake's spine bones and found that V. indicus could have ranged from between 36 feet and 50 feet (11 and 15 m) long, although they acknowledge there may be a possible error associated with their estimate. [Source: Jacklin Kwan, Live Science April 19, 2024]

The researchers used two methods to come up with possible ranges for V. indicus' body length. Both used present-day snakes to determine the relationship between the width of a snake's vertebrae and its length — but they differed in the datasets they used. One used data from modern snakes in the Boidae family, which includes boas and pythons and contains the largest snakes alive today. The other dataset used all types of living snakes. "Vasuki belongs to an extinct family of snakes, distantly related to pythons and anacondas, and so when you're using existing snakes to estimate body length, there may be uncertainties," study co-author Debajit Datta, a postdoctoral researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, told Live Science. The upper end of their estimations would make V. indicus even bigger than Titanoboa cerrejonensis.

V. indicus belongs to a group of snakes known as Madtsoiidae, which first appeared in the late Cretaceous period (100.5 million to 66 million years ago), in South America, Africa, India, Australia and Southern Europe. Looking at the sites where ribs would attach to the vertebrae, the researchers think V. indicus had a broad, cylindrical body and mostly lived on land. Aquatic snakes, in comparison, tend to have very flat, streamline bodies. Due to its large size, the researchers say the snake was likely an ambush predator, subduing its prey by constriction, similar to modern-day anacondas.

The scientists estimate that V. indicus thrived in a warm climate with an average of around 82 degrees Fahrenheit (28 degrees Celsius) — significantly warmer than the present day. "There are still many things we don't know about Vasuki. We don't know about its muscles, how it used them or what it ate," Datta said. Sunil Bajpai, study co-author and a vertebrate paleontologist at IIT Roorkee, said the team hopes to have the fossils analyzed for their carbon and oxygen content, which may reveal more about the snake's diet.

Snake Characteristics

A snake's internal organ have been shrunken, stacked on top of one another and ingeniously engineered to fit in their body. Their skeleton consists of flexible backbones and dozens of pairs of ribs. Their skins is covered by scales and is generally dry to the touch.

Most snakes have only one lung. It is exceptionally long, reaching well into the snake’s body. When the lung is full of air it looks almost as if the snake has swallowed another snake. Snakes lack a diaphragm muscle to push their lungs. Their rib muscles which expand the chest during each breath also propel the body forward when the snake moves.

Snake scales don't grow so the skin has to be shed when the snake gets bigger. Snakes shed their skin several times a year. Before this occurs their skin color is dull and their eyes are milk colored. Snakes are partially blind at this time and usually try to stay hidden. A couple of days before the shedding begins, the color returns to the skin and eyes. An oily secretion collects under the old skin and loosens it, and the skin cracks at the lips. The snake rolls back the skin, often with the help of a rock, and begins crawling out, rolling the skin inside out like a glove as it moves out. The eyes covers are shed along with the skin.

The skins from cobras, pythons, lizards, water snakes and other snakes has a beautiful texture and patterns. They are used to make expensive shoes, handbags, luggage, belts and garments. The bright colors found on some poisonous snakes is a warning to potential predators that the snake is dangerous to them. Some non-poisonous snakes have patterns that mimic poisonous snakes , which are intended to scare off predators. Occasionally you get bright blue rattlesnakes due to a genetic defect.

Some snakes dig burrows. Most of those that do — along with other legless creatures that dig burrows — usually rely on their heads to excavate or compact earth. The eastern hognose snake has a protuberance on its head that helps it scrape away the soil and compact it upwards, The Louisiana pine snake loosens sand and soil with its “nose” and “hoes” it out by bending its head downward. The shield nose cobra move sits head from side to side, scraping the soil and with its flat shield, the Saharan pit viper buries itself by flexing its side and twisting to scoop out sand. [Source: Natural History, December 2006]

The only vocal sounds that most snakes make are hisses. Some growl. Snakes of all species shake their tails when agitated, but only rattlesnakes can make a noise with their tails. Some species of snake play dead when they sense danger.

Lizard and Snake Senses

Lizards have movable eyelids (snakes don't have these) and most species have excellent eyesight. Some species of lizard even have a "third eye." on top of their head. This eye does not form an image but may help a lizard distinguish between light and dark. Lizards also have external eardrums and can hear very well.

Lizards and snakes are both very good at sensing and analyzing smells and message-carrying chemicals Many have a vomeronasal organ embedded in the roof of the mouth that detects heavy non-airborne molecules taken in through the mouth. It supplements olfaction which is the ability to smell airborne molecules that enter the nostrils and is distinct from taste, which analyzes chemicals that come into contact with taste buds on the tongue. These senses help reptiles locate prey and help warn them or potential prey that might be toxic. It also frees up the eyes to locate prey and find mates.

The vomeronasal organ is sometimes called the Jacobsen's organs. Lizards and snakes with forked tongues have these on either side of the roof of their mouth. Chemicals are picked up from the environment with their forked tongues then transfer to these organs.

Lizards and snakes with forked tongues constantly flick their tongues in and out of their mouths, bringing in new samples of chemicals on either side of the tongue through the chemical equivalent of stereoscopic vision. Not only can they determine the presence of chemicals they can also determine the direction which they are coming from and detect edges and dimensions of the sources. .

Snakes use forked tongue and sense organs in their mouth to locate food, enemies and mates . And this they can do without even opening their mouths. Predators rely on smells and message-carrying chemicals to locate their prey and use eyes to determine the location of the prey for the final lung.

Snake Senses

Snakes have keen senses of smell, temperature and touch but generally have poor eyesight (except night snakes that have catlike eyes). Snakes don't have movable eyelids, and consequently they can not blink. Their eyes are covered and protected by transparent scale called a brille. Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: In their process of adapting to an underground lifestyle, snakes gave up their external ears and eyelids. Like most reptiles, snake vision is designed for picking up movement of potential prey, rather than separating stationary objects. Their finest sense, however, rests in their very well-developed Jacobson's organs. These organs, which sense pheromones and other invisible chemical messengers, come in pairs, and are located to the right and left inside the mouth. The forked tongue so characteristic of snakes is actually designed to collect pheromone samples from the air and ground. When retracted the respective tongue tips are placed against the right and left Jacobson's organs, allowing the snake to compare the results and compute from which direction the pheromones are coming.

Like most reptiles, snake vision is designed for picking up movement of potential prey, rather than separating stationary objects. Their finest sense, however, rests in their very well-developed Jacobson's organs. These organs, which sense pheromones and other invisible chemical messengers, come in pairs, and are located to the right and left inside the mouth. The forked tongue so characteristic of snakes is actually designed to collect pheromone samples from the air and ground. When retracted the respective tongue tips are placed against the right and left Jacobson's organs, allowing the snake to compare the results and compute from which direction the pheromones are coming.

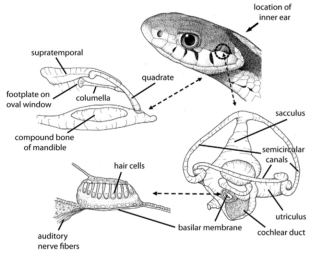

Unlike lizards, snakes don't hear very well. Although most snakes are deaf or nearly deaf, they do have internal ear-bones that enable them to hear some very low frequency sounds, but function mainly to detect minute ground vibrations. Snakes lack eardrums external ears, which are believed to have been lost from when they first evolved underground from burrowing reptiles millions of years ago. They have retained some of their ear bones and can sense vibrations through their jaws.

Rattlesnakes, pit vipers and other snakes have heat-sensitive, infra-red-detecting facial pits that allow them to detect prey several meters away. Information from the pits and eyes is processed in same area of the brain, allowing the snakes to “see the body heat of an animal perhaps as a brighter image.” Some animals have built in defenses against a rattlesnakes heat sensing capabilities. Ground squirrels keep their tail cool when they sense most kinds of snakes. But if a rattlesnake comes near they heat up their tails and furiously move them from side to side — a process called tail wagging — to thwart an attack.

Snakes Have the Ability to Evolve Very Fast

snake pit organs

Snakes appear to evolve very quickly — at much faster rates than other reptiles —allowing them to adapt and diversify and spread across the world. "Snakes are like the Big Bang 'singularity' in cosmology — a dramatic expansion of diversity in species and their ecologies, linked to some event that might have occurred early in the evolutionary history of snakes," Pascal Title, a evolutionary macroecologist at Stony Brook University in New York, said in a statement released in conjunction with a study published February 22, 2024 in the journal Science. [Source:Hannah Osborne, Live Science, February 23, 2024]

Hannah Osborne wrote in Live Science: The researchers investigated what makes animal groups evolutionary winners — in particular, why certain groups are able to diversify into more species and appear better at surviving events like mass extinctions — study author Daniel Rabosky, an evolutionary biology at the University of Michigan, whose research focuses on macroevolution, told Live Science. The scientists looked at squamates, the order of reptiles that includes snakes and lizards and includes over 11,000 species. In this group, snakes, in particular, are widely diverse — the roughly 4,000 known snake species vary from venomous sea snakes, giant constrictors and hooded cobras to tiny threadsnakes that burrow to feed on ants and termites.

To find out why snakes are such an evolutionary success story, the researchers carried out a huge study of the genomes of almost 1,000 snakes and lizards. They also examined dietary preferences by looking at the stomach contents of over 60,000 museum specimens and field observations. With this data, they built up a comprehensive evolutionary tree of bodily and dietary changes in the group over time. They then used mathematical and statistical models to look at how snakes and lizards evolved.

Their findings suggest that snakes underwent several evolutionary explosions and evolved three times faster than lizards, in terms of diversity. After likely first emerging about 128 million years ago, there was a huge burst at some point between then and 70 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago), and another major pulse after the dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous.

This fast rate of evolution continues to this day, the team's models show. "Compared to lizards, they have changed relatively rapidly, and they've continued to do so through time," Rabosky said. "So we would also say that the continued 'evolutionary explosion' of snakes is still ongoing today and appears partly driven by the fact that the rate of evolution — their 'evolutionary clock' so to speak — is just ticking a lot faster than many other groups of animals. This fast-ticking-evolutionary-clock is really important because it lets snakes evolve new traits quickly that can take advantage of opportunities that come up."

Snakes' evolutionary flexibility enables them to change their body shape and diets "very quickly," he said. The initial "singularity" that led to snakes' success appears to have started with them developing limbless bodies, flexible skulls and advanced chemical-detection systems.

These changes enabled them to target a huge array of prey, providing the framework for individual species to develop and specialize. Previous research published in 2021 shows the diversity in their diets exploded after the dinosaurs went extinct, with snakes quickly evolving new adaptations to take advantage of the new world they found themselves in — a dinosaur-less world in which mammals were starting to gain a foothold. But why snakes ended up with a fast evolutionary clock in the first place is still a mystery. "This is the big question for us," Rabosky said. "We can’t really explain this yet.”

Legless Lizards

Legless lizards refer members of several groups of lizards that have independently lost limbs or have limbs so small you can barely see and can not be used to move around. Ones belonging to the family Pygopodidae look just like snakes except they have eyelids and external ear openings which snakes don’t have and lack broad belly scales which snakes have. Legless lizards also often have a notched rather than forked tongue, two more-or-less-equal lungs (most snakes have one) and have a very long tail (by contrast snakes have a long body and short tail). [Source: Wikipedia]

Most legless lizards are either long-tailed surface dwellers that “swim” through grass or short-tailed burrowers. The surface dwellers have long tails that can be bitten off by predators without causing serious harm to the lizard. Burrowers that live underground don’t need this defense. Every stage of reduction of the shoulder girdle — including complete loss — occurs among limbless squamates, but the pelvic girdle is never completely lost regardless of the degree of limb reduction or loss. At least the ilium is retained in limbless lizards.

Many families of lizards have independently evolved limblessness or greatly reduced limbs including the following examples: 1) Anguinae, an entirely legless subfamily native to Europe, Asia, North America and North Africa, that contains well-known species such as slowworms, glass snakes and glass lizards; 2) Cordylidae, an African family of 66 species, with one virtually legless genus Chamaesaura, containing five species with hindlimbs reduced to small scaly protuberances; 3) Pygopodidae, with 44 species, almost all of which are endemic to Australia. Pygopodids are not strictly legless since, although they lack forelimbs, they possess hindlimbs that are greatly reduced to small digitless flaps, hence the often used common names of "flap-footed lizards" or "scaly-foot".The pygopodids are considered an advanced evolutionary clade of the Gekkota, which also contains six families of geckos. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, CNN, BBC, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025