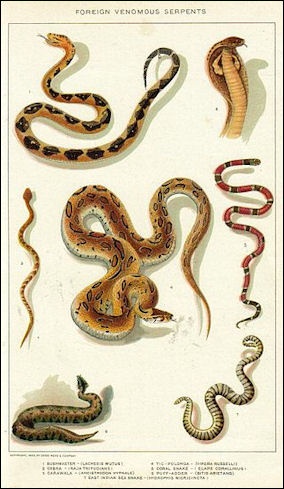

VENOMOUS SNAKES

There are 250 to 400 venomous snakes depending on how they are counted. They include true vipers, pit vipers, cobras, and sea snakes . Even snakes like garter snakes that are not regarded as venomous actually are. Garter snakes produce a small amounts of venom, just enough to slow down prey such as frogs so they can immobilize and swallow them. The development of venom was seen as key to snake evolution, allowing them to shed their muscles and become more mobile and quick by negating their reliance on constriction as a means of subduing their prey.

Primitive back-fanged snakes have poisonous glands above their teeth and inject poison via grooves in their teeth. These snakes often have very potent poison but the need to maintain a grip and chew for a while to inject enough to kill or immobilize their prey.More advanced snakes have fangs on the front of their upper jaws and enclose venom glands that connect to tubes in the fangs that enable them to inject poison. Cobras, mambas and sea snakes have short and immobile fangs.

The fangs of vipers, which includes rattlesnakes, are much longer. They are so long they have hinges and lie folded up on the roof of the mouth until they are needed: then they flip into position when the mouth opens wide and the bone to which they fangs are connected rotates. The fangs are ready immediately. When they strike their prey they inject their venom like hypodermic needles. The fangs are periodically changed. Rattlesnakes shed their fangs every 60 days.

Venomous (poisonous snakes) need their venom to immobilize prey (they don't use it to kill prey necessarily) and defend themselves. To avoid injury from the claws and bites of large prey, snakes aim to immobilize it as quickly as possible with venom. According to Live Science: Pretty much every person on Earth lives within range of an area inhabited by snakes, researchers reported in 2018 in a study published in the journal The Lancet. Snakes make their homes in deserts, mountains, river deltas, grasslands, swamps and forests, as well as saltwater and freshwater habitats. After natural disasters, such as floods or wildfires, snakes often move into populated areas that they previously avoided — they may even seek shelter in houses, according to the CDC. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science, June 2, 2019]

RELATED ARTICLES:

VENOMOUS SNAKE BITES: ANTIVENOMS, WHAT TO DO AND NOT DO factsanddetails.com

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN ASIA: KRAITS AND RUSSELL'S, SAW-SCALED AND PIT VIPERS factsanddetails.com

SNAKES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, LARGEST, SENSES, FEEDING, BREEDING factsanddetails.com

SNAKE BEHAVIOR: MOVEMENT, FEEDING, BREEDING factsanddetails.com

COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM, BITES, TREATMENTS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS IN ASIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, VENOM factsanddetails.com

INDIAN COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITES factsanddetails.com

KING COBRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

COBRAS AND HUMANS: FESTIVALS, SNAKE CHARMERS, ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

UNUSUAL SNAKES IN ASIA: FLYING, CARTWHEELING AND TENTACLED ONES factsanddetails.com

PYTHONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HUNTING, PREY factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Snakes: Snake World snakesworld.info ; National Geographic snake pictures National Geographic ; Snake Species List snaketracks.com ; Herpetology Database artedi.nrm.se/nrmherps ; Big Snakes reptileknowledge.com ; Snake Taxonomy at Life is Short but Snakes are Long snakesarelong.blogspot.com; Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Difference Between Poisonous and Venomous

Venomous is the correct term for snakes with poison. If you call them poisonous technically that means they are poisonous to eat, like poisonous mushrooms. Ethan Freedman told Live Science, The terms "venom" and "poison" are not interchangeable. Venom is injected directly by an animal, whereas poison is delivered passively, such as by being touched or ingested. "If you bite it and you get sick, it's poisonous. If it bites or stings you and you get sick, then it's venomous," said Jason Strickland, a biologist at the University of South Alabama who studies venom. In a research article published in 2013 in the journal Biological Reviews, scientists proposed a third category of natural toxins: the "toxungens." Toxungens are actively sprayed or hurled toward their victim without an injection. For example, spitting cobras can spew toxins from their fangs.[Source:Ethan Freedman, Live Science, March 27, 2023]

Poison and venom don't always work the same way. For example, venom won't necessarily hurt someone unless it enters the bloodstream, according to the University of Florida Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation. No matter how they're delivered, these toxic chemicals are highly effective weapons in the evolutionary arms race between predator and prey. And in some cases, a single animal can employ its toxins on both offense and defense.

Spitting cobras, like the black-necked spitting cobra (Naja nigricollis) and the Philippine cobra (Naja philippinensis), spit out toxins in self-defense when confronting a threat and inject venom into their prey to hunt, making them both toxungenous and venomous creatures. Sometimes, two different methods are used for the same purpose. The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) defends itself with toxins on its skin and toxins squirted from its eyes, making it both toxungenous and poisonous.

extracting venom

Biologically, all of these toxic substances are also incredibly diverse. Venom alone has independently evolved more than 100 times, in creatures as varied as snakes, scorpions, spiders and cone snails, Strickland said. They're also pretty common — by at least one estimate, around 15 percent of all animal species on Earth are venomous. And many of these natural toxins are made up of compounds that work in different ways. For example, the neurotoxins (like those found in mamba snake venom) assault the nervous system, while the hemotoxins (like those found in copperhead snake venom) wage war on an animal's blood. Some Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) venom actually has both neurotoxins and hemotoxins, making these venomous animals potentially "a very unpleasant species to get bitten by," Strickland said.

These different attack modes can reflect how the toxin is used. For example, venomous ants often use their venom as a defense mechanism, so it causes immediate pain to banish intruders. Snake venom, by contrast, incapacitates its victim so the snake can feed, Strickland pointed out. Meanwhile, some poisonous animals can cause immediate death if ingested, such as poison dart frogs in the genus Phyllobates. These creatures use batrachotoxin, which impairs electrical signaling in the body, effectively stopping cardiac and neuronal activity. Any predator that eats them won't live to eat another poison frog.

Yet some nontoxic creatures have managed to keep pace with their toxic adversaries. Opossums seem to have developed resistance to snake venoms, and grasshopper mice actually appear to get a pain-relieving effect from the stings of bark scorpions. If the distinctions between poisons, venoms and toxungens seem a little arbitrary, it's because they sort of are; in some languages, there is only one word for both "venom" and "poison." In Spanish, for example, both are translated as "veneno," and in German, both are translated as "Gift."

Snake Venoms

Bites by venomous (poisonous) snakes can result in a wide range of symptoms, from simple puncture wounds to life-threatening illness and death.There are many kinds of venom. The two main types are 1) neurotoxins, which paralyze parts of the nervous system, especially those governing breathing and heart activity, and 2) hemotoxins, which destroy blood and tissue. Some snakes have poison with both neurotoxins and hemotoxins. Others have coagulants, which cause clotting of the blood, or anticoagulants, which prevent clotting and cause extensive bleeding. The tiger snake and taipan of Australia and certain species of sea snake possess the most toxic poisons. While toxicity is a concern some scientist believe that the viper family can be deadlier because even though their toxicity level is lower they inject a lot more venom.

All snake venom has both neurotoxins and hemotoxins in it, but some snakes have more neurotoxic venom and others have more hemotoxic venom. There are antivenoms (antivenins) to treat mot but not all snake venoms. Neurotoxins affects the nervous system (the brain and nerves). They can destroy or paralyze the nerves that control the heart and breathing. Victims may die from lack of air or heart failure. Hemotoxins attack blood cells and also destroy both muscles and blood vessels. Hemotoxic venoms allow blood to leak into the surrounding tissue, causing severe swelling, pain, and discoloration at the site of the snakebite. Victims may die from kidney failure or shock. [Source: United States Army, Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine (USACHPPM), Entomological Sciences Program, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md 21010-5403]

Venom is first and foremost a feeding adaption used to subdue prey. Victims of snake bites are paralyzed and can do nothing as they are swallowed head first. By using venom to immobilize its prey, a venomous snake has to rely even less on a strong bite to achieve the same objective. Venomous snakes manufacture their poison internally unlike poison dart frogs and some sea creatures which acquire their toxins from the food they eat. Snakes have a dozen or so different glands in their head and many of these produce toxic secretions. Venom production can vary with the season and takes approximately a month to replenish itself after it has been used. Studies of the Persian and African Saw-scaled vipers indicate that production of venom increases in the summer and falls off in the autumn and winter, a cycle that parallels the natural feeding and fasting rhythm of snakes.

How is the potency of snake venom measured. One method is to inject venom into a group of mice. the amount of venom that kills 50 percent of the mice in 24 hours is called the lethal dose, or LD50, and is measured in milligrams of venom per kilogram of mouse. The lower the LD50 number the more powerful the toxin is. The LD50 of a taipan from Australia is 0.25 milligrams. For the king cobra and western diamondback rattlesnake it is 1.7 milligrams and 18.5 milligrams respectively.

How Snake Venoms Work

snake bite

Herpetologist and toxinologist Zoltan Takacs, a research associate and assistant professor at the University of Chicago, said purpose of venom is to immobilize and kill. It aims precisely at vital targets, including the connections between nerve and muscle cells, or the circulatory system. Toxin-target contact can cause respiratory paralysis or shock. If this contact is disrupted, the toxin has no effect. When venom is injected into the snake that produces it, nothing happens. Takacs' team discovered why, by comparing the targets of toxins (receptors) on muscle cells in cobras with receptors in humans and other mammals. [Source: University of Chicago News, May 19, 2010]

Snake venoms begin acting in seconds: with enzymes in the venom breaking down tissues; blood and other fluids beginning to leak into tissues; and blood losing its ability to clot. Snake venom strength varies depending on the age of the snake, when it last ate, the time of day the strike occurs, how deeply the fangs penetrate the skin and how much venom is injected.

Some venoms contain 130 ingredients and scientist still don’t understand how they interact and cause the reactions they do. "There are blood clotting agents," Adrian Forsyth wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "substances that reduce blood clotting; others that specifically destroy red blood cells, white blood cells and the cells of other tissues; bacterial agents; and compounds that stimulate digestion. Cobras, kraits and coral snakes have a toxin that can stop a prey's heartbeat."

Carl Zimmer wrote in the New York Times: “The intricate shape of snake venom molecules allow them to lock onto particular receptors on the surface of the cells or onto specific proteins floating in the blood stream. Some venom molecule can plug the channels that muscle cells use to receive signals from neurons to contact. Without the signals the muscles go flaccid, leading to asphyxiation. Other venoms send the immune system into a tailspin, making it attack the prey’s organs. Still others loosen blood vessel walls, leading to shock and bleeding. Rather than rely on one of these attacks most venomous snakes produce a cocktail of molecules.”

Advances in DNA analysis have greatly aided the study of snake venom. Sequencing the proteins found in venom used to be done at a rate of three a month but new technologies have enabled scientists to do them at about 2,000 a month. Scientists have been able to identify all the genes that are active in venom glands cells; realize that snake venoms originated in one ancient species and was passed on to ancestor species rather than evolving independently in different species; and that many of the toxins developed in other part of the body such as brain, liver and blood not the venom glands.

Many snakes venoms contain coagulants and anticoagulants. Compounds similar to snake venom are now being used to treat anti-blood clotting disorders in humans. Venom from the saw-scaled viper has been used to design drugs that treat blood clots by prevented the blood from coagulating by keeping the blood platelets from sticking together.

Vipers

pit organ of a viper

There are about 40 species of true vipers. Among them are the common adder of Europe, the puff adder and horned viper of northern Africa, the sand viper, and rattlesnakes of the Americas. With the exception of one African species all true vipers give birth to live young.

Vipers are regarded as the most highly evolved of all snakes. Other snakes have more potent toxins than vipers but vipers have longer fangs and a better system for delivering poisons deep into the victims flesh plus a spade-shaped head able to accommodate the large venom glands.

Vipers have enlarged fangs that spring up when the viper opens its mouth and point forward, ideal for inflicting a bite. They can also make their upper jaws which holds the fangs stand up. This springs the fangs close to the victims. This allows them to strike prey and recoil and track down the prey later and avoid being injured by claws or teeth in a fight.

The largest and most dangerous viper is the Russell's viper, or daboia of India and South Asia. A man in Sri Lanka that nearly died from a bite from this snake told Reuters, “I was seeing everything double, so I knew the venom had broken into my body. After that I threw up foul green stuff from by body.” He suffered from severe bleeding, neurological problems and kidney failure. It took a whopping 110 vials of antivenin to save him.

Pit Vipers

There are about 60 species of pit vipers. They live mostly in Latin America. Pit vipers look like rattlesnakes. They have: 1) huge poison glands that puff out their cheek and give their head a triangular shape; 2) long hollow fangs in the front of the mouth that are folded down when the mouth is closes but automatically open when the mouth opens. 3) hunts in day and at night. They have heat sensitive glands that allow them to locate birds and mammals in the dark.

Pit vipers hunt frogs and small mammals. Despite their fearsome appearance they are shy creatures that avoid human contact. Rattlesnakes give birth to live young.

Rattlesnakes and pit vipers are adept at detecting heat. They have infrared sensors near their nostrils that allow to locate prey by sensing their heat. Pit vipers can strikes a mouse using these sensors even when they are blindfolded.

Snakes and Animals

Many animals either have an innate fear os snakes or develop a fear at an early age. Even newborn monkeys jump back when they are shown an image of a snake.

Many animals such as hawks, eagles, other birds, mongooses and predatory cats feed on snakes, especially young snakes. For defense snakes try to avoid detection by being inconspicuous, quiet and hidden or positioned someplace they can quickly seek cover When under attack snakes use the same methods as defense that use when attacking.

Other techniques that snakes used to fend off attackers include: 1) intimidation, using a noisemaker such as a rattle, hissing or expand their bodies so they look bigger than they actually are); 2) defecating when they are attacked to gross out their attackers; 3) feigning death; 4) getting attackers to harmlessly attack the snakes tail.

Most Venomous Land Snakes in Australia

1) Inland Taipans by many reckonings are the world’s most venomous snakes. According to the International Journal of Neuropharmacology their venom is very toxic and little bit can go a long way. These snakes favor in the clay crevices in Queensland and South Australia's floodplains, often within the pre-dug burrows of other animals. Because they live in more remote locations than coastal taipans, inland taipans rarely come into contact with humans. When inland taipans feels threatened, they coils their body into a tight S-shape before darting out in one quick bite or multiple bites. A main ingredient of this venom, which sets it apart from other species, is the hyaluronidase enzyme. According to a 2020 issue of Toxins journal (Novel Strategies for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Snakebites), this enzyme increases the absorption rate of the toxins throughout the victim's body. [Source Jeanna Bryner, Live Science, August 31, 2021]

2) Eastern Brown Snakes live mostly in eastern Australia and are responsible for more human fatalities than any other snake species in Australia. Their venom is very powerful, containing powerful toxins that can cause paralysis and internal bleeding. The initial bite is often painless, according to the Australian Museum. "They're the only snakes in the world that regularly kill people in under 15 minutes," Bryan Fry, who studies venom at the University of Queensland, told ABC News in 2024. "Even more insidiously than that is that for the first 13 minutes, you're going to feel fine." They generally hunt during the day and are often found in the suburbs of cities and large towns, putting them in close contact with humans. Many eastern brown snake bites are the result of people trying to kill them.

3) Coastal Taipans live in wet forests of temperate and tropical coastal regions in coastal areas of Australia. They are incredibly fast, able to jump into the air fangs-first to attack a victim multiple times before they are aware of what hit them, according to the Australian Museum. When threatened, coastal taipans lift their whole body off the ground and can jump with extraordinary precision. Before 1956, when an effective antivenom was produced, this snake's bite was nearly always fatal, according to Australian Geographic. The snake's venom contains neurotoxins, which prevent nerve transmission.

4) Tiger Snakes (Notechis scutatus) have powerful venom and kill an average of one human a year according to the University of Adelaide. Tiger snakes are fairly large and live mainly in southern Australia, including its coastal islands and Tasmania. Members of the genus Notechis,they are often observed and usually ground-dwelling, through they are able to swim and climb into trees and buildings. Tiger snakes are identifiable by their banding — black and yellow like a tiger — although their coloration and patterning can be highly variable. Their diverse characteristics have been classified either as distinct species or by subspecies and regional variation.

5) Common Death Adders are another deadly snake in Australia. Before the introduction of antivenom in the 1950s, about 60 percent of common death adder bites were fatal. According to Live Science: Common death adders are found across coastal areas of southern, eastern and northern Australia. They are recognizable thanks to their broad, triangular heads, short, thick bodies and thin tails. Common death adders are ambush predators and wait for prey — including frogs, lizards and birds — under leaves until they are ready to strike. Bites to humans are rare and normally involve a person stepping on one by accident. Their venom causes paralysis and can lead to death.

RELATED ARTICLES:

VENOMOUS SNAKES IN AUSTRALIA: VENOM, SPECIES, BITES, AVOIDANCE, TREATMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com

TAIPANS (WORLD'S DEADLIEST SNAKES): SPECIES, VENOM, BITES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

TIGER SNAKES: CHARACTERISTICS, REGIONAL MORPHS, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BROWN SNAKES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, VENOM, BITE VICTIMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Most Venomous Snakes in Asia

1) King Cobras are the longest venomous snakes in the world measuring up to 5.4 meters (18 feet), according to the Natural History Museum in London. Jeanna Bryner wrote in Live Science: The snake's impressive eyesight allows it to spot a moving person from nearly 100 meters (330 feet) away, according to the Smithsonian Institution. When threatened, a king cobra will use special ribs and muscles in its neck to flare out its "hood" or the skin around its head; these snakes can also lift their heads off the ground about a third of their body length, according to the San Diego Zoo. Its claim to fame is not so much the potency of its venom, but rather the amount injected into victims: Each bite delivers about 7 milliliters (about 0.24 fluid ounces) of venom, and the snake tends to attack with three or four bites in quick succession, the Fresno Zoo reported. Even a single bite can kill a human in 15 minutes and an adult elephant in just a few hours, Sean Carroll, molecular biologist at the University of Maryland, wrote in The New York Times. [Source Jeanna Bryner, Live Science, August 31, 2021]

2) Banded Kraits (Bungarus fasciatus) move slowly during the day and are much more likely to bite after dark. So named because its body has broad black bands mixed with white narrow bands in between, this mid-sized snake reaches maximum length of 1.9 meters and has a small but non-triangular head with no pit.The snake's venom can paralyze muscles and prevent the diaphragm from moving, according to a 2016 study published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. This stops air from entering the lungs, effectively resulting in suffocation.

banded krait

3) Saw-Scaled Vipers (carpet viper, Echis carinatus) cause more human fatalities that any other snake in the world. Reaching lengths of 60 centimeters (two feet) and ranging from West Africa to India, these relatively small snakes have a bite that causes severe bleeding and fever. The saw-scaled viper is mostly found in the dry regions of Africa, the Middle East, Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka. They have a characteristic threat display, rubbing sections of their body together to produce a "sizzling" warning sound. Eight species are currently recognized. There is an antivenin. Saw-scaled vipers are with brown, beige and white patterning, which helps camouflage it among dirt and dried grass. Saw-scaled vipers and the Russel's viper may be responsible for about 58,000 deaths a year in India alone.

4) Russell's Vipers are found in Asia throughout the Indian subcontinent, much of Southeast Asia, southern China and Taiwan. They reach lengths of 1½ meters and are marked with dark-brown blotches, edged with white, on a lighter background. They have a well deserved reputation for aggressiveness and striking without warning. According to research published March 25, 2021, in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases these snakes are responsible for the majority of snake bite deaths in India. In Sri Lanka, where this nocturnal viper likes to rest in paddy fields, they cause high mortality among paddy farmers during harvest time.

Russell's viper venom causes internal bleeding. Bites from this snake are relatively common and the mortality rate is moderate. There is an Antivenin. The venom has a clotting agent that useful in the treatment of hemophilia. The snake's venom can cause acute kidney failure, severe bleeding and multi-organ damage, researchers reported in the Handbook of Clinical Neurology in 2014. Some components of the venom related to coagulation can also lead to acute strokes, and in rare cases, symptoms similar to Sheehan's syndrome in which the pituitary gland stops producing certain hormones. Victims typically die from renal failure, according to the handbook.

Most Venomous Snakes in Africa

1) Black Mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis) are Africa's deadliest snakes. Named for the dark, inky color inside of their mouths, black mambas are actually brownish in color. They average around 2.5 meters (8 feet) in length. Fast as well as deadly, these are thought to be responsible for up to 20,000 deaths a year, though precise numbers are hard to come by. They can kill a person with just two drops of venom. [Source Jeanna Bryner, Live Science, August 31, 2021]

According to Live Science: Black Mamba venom belongs to the class of three-finger toxins, meaning they kill by preventing nerve cells from working properly. The snakes are born with two to three drops of venom in each fang, so they are lethal biters right from the get-go. By adulthood, they can store up to 20 drops in each of their fangs, according to Kruger National Park. Without treatment, a bite from this African snake is just about always lethal. In the case of the black mamba, the venom prevents transmission at the junction between nerve cells and muscle cells, causing paralysis. The toxin may also have a direct effect on heart cells, causing cardiac arrest.

That was the case for a South African man who got bitten by a black mamba on his index finger, Ryan Blumenthal, of the University of Pretoria, reported in The Conversation. By the time he got to the hospital, within 20 minutes, he was already in cardiac arrest. Even though doctors treated him with antivenom, the man ended up dying days later, Blumenthal said.

Black mambas can move at around 19 kilometers per hour (12 mph). They live in savannas, open woodlands, and rocky hills, according to the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), and like to sleep in hollow trees, abandoned termite mounds and in the cracks between rocks. Black mambas live in large swaths of sub-Saharan Africa, in the following countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Mozambique, Eswatini, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Angola, according to SANBI.

2) Boomslangs (Dispholidus typus) are blue and green and produce a venom causes victims to bleed internally. According to Live Science: About 24 hours after being bitten on the thumb by a juvenile boomslang (also called a South African green tree snake), herpetologist Karl Patterson Schmidt died from internal bleeding from his eyes, lungs, kidneys, heart and brain, researchers reported in 2017 in the journal Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. The snake had been sent to Schmidt at The Field Museum in Chicago for identification. Like others in the field at the time (1890), Schmidt believed that rear-fanged snakes like the boomslang couldn't produce a venom dose big enough to be fatal to humans. They were wrong.

The boomslang, which can be found throughout Africa but lives primarily in Swaziland, Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, is one of the most venomous of the so-called rear-fanged snakes, according to the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Such snakes can fold their fangs back into their mouths when not in use. As in other deadly snakes, this one has hemotoxic venom that causes their victims to bleed out internally and externally, the Museum reported.

With an egg-shaped head, oversized eyes and a bright-green patterned body, the boomslang is quite the looker. When threatened, the snake will inflate its neck to twice its size and expose a brightly colored flap of skin between its scales, according to the SANBI. Death from a boomslang bite can be gruesome. As Scientific American describes it: "Victims suffer extensive muscle and brain hemorrhaging, and on top of that, blood will start seeping out of every possible exit, including the gums and nostrils, and even the tiniest of cuts. Blood will also start passing through the body via the victim's stools, urine, saliva, and vomit until they die." Luckily, there is antivenom for the boomslang if a victim can get it in time.

Most Venomous Snakes in the Americas

9) Fer-de-Lances are grey and brown pit vipers from Central and South America. A bite from a fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper) can turn a person's body tissue black as it begins to die, according to a 1984 paper published in the journal Toxicon. These pit vipers, which live in Central and South America and are between 3.9 and 8.2 feet (1.2 and 2.5 m) long and weigh up to 13 pounds (6 kg), are responsible for about half of all snakebite venom poisonings in Central America, according to a 2001 study published in the journal Toxicon.

Viper venom belongs to a class of proteins called metalloproteases. These can digest tissue, causing tissue to die (necrosis), swell (edema) or bleed, Barua said. Fer-de-lance venom is also an anticoagulant (a substance that hinders blood clotting), a bite from this snake can cause a person to hemorrhage. And if that didn't scare you off, consider this: A female can give birth to 90 fierce offspring, according to the University of Costa Rica.

2) Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes (Crotalus adamanteus) are the biggest venomous snake in the U.S., and is found across southeastern states, including Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi and Louisiana. According to Live Science: They are ambush predators and tend to lie quietly coiled away waiting for prey to approach. They can strike a victim up to two-thirds of their body length away, injecting a large quantity of venom with each bite. The species is not aggressive to humans, and bites tend to occur if a snake is intentionally harassed or accidentally stepped on, according to the Florida Museum. Their venom, which the snakes administer in about 75 percent to 80 percent of bites, kills red blood cells and causes severe tissue damage. If left untreated, the fatality rate for an eastern diamondback bite is between 10 percent and 20 percent.

Venomous Snake Scientist Zoltan Takacs

Herpetologist and toxinologist Zoltan Takacs, a research associate and assistant professor at the University of Chicago, was named to the 2010 class of National Geographic Emerging Explorers. Takacs. Combines his interest in drug development with exotic travel, venomous snakes and professional photography, is one of 14 "visionary, young trailblazers" from around the world making a "significant contribution to world knowledge through exploration while still early in their careers." [Source: University of Chicago News, May 19, 2010]

Fascinated from a young age with nature, Takacs captured and bred snakes in his room as a boy (and fortunately recaptured one viper that escaped to his parents' bedroom for a few days). He studied pharmacology in Hungary, then earned a PhD from Columbia University in New York. Analyzing venom may confine Takacs to a lab, but collecting it takes him to the far corners of the world. "Since I need venom and DNA samples from snakes, their prey and predators, my work requires unconventional travel strategies and ventures into unfamiliar territories-exploration I absolutely love." Takacs usually travels solo with only a backpack, camera bag and a tissue-collecting kit, often piloting small planes or riding camels to reach remote destinations. His quest for venomous creatures has taken him to 133 countries. The expeditions are never uneventful.

One of his first, as a teen, landed him in a Bulgarian military jail near the Greek border. He has used military escort against pirates while diving for sea snakes in the Philippines; helicopter evacuation from civil war in Laos; dodged stampeding elephants in the jungles of Congo; survived his due number of bites by an assortment of venomous vipers and venom spewed in his face by a spitting cobra. Repeated exposure made Takacs allergic to snake venom, snake antivenom and snake saliva. Yet he doesn't wear much protective gear. "Gloves limit my fine-motor movement, and I need that," he said. I only wear gloves underwater when catching sea snakes. This is the norm in this business.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Natural History magazine, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, The Economist, BBC, and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025