PANGOLINS — THE WORLD'S MOST POACHED ANIMALS

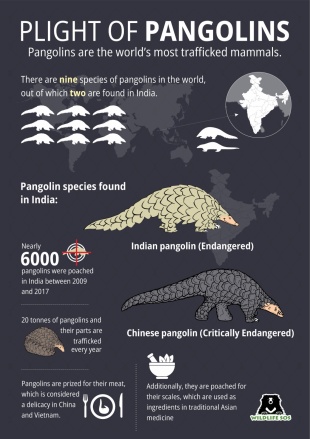

The biggest victim of the wildlife trade is not elephants, rhinos, or tigers — its pangolins, whose meat is a prized delicacy and scales are greatly sought after for traditional medicines. According to the World Wildlife Fund, pangolins are the most trafficked and poached animal in the world. An estimated 300 of them are poached every day on average. All eight species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List threatened species, most of as endangered or critically endangered. The Pangolin Specialist Group estimates that over one million pangolins were poached between 2014 and 2024. The animals rights group TRAFFIC estimated one million pangolins were poached from 2000 through 2013. According to a 2020 United Nations report on wildlife crime, between 2014 and 2018, more than 370,000 pangolins were seized, and that is only a fraction of those trafficked.

"Pangolins are by far the most common species of mammal in international trade, with animals being taken from all across Asia to meet the demand for use in traditional medicines, and for meat, largely in China," says Chris Shepherd, the Deputy Regional Director in Southeast Asia of TRAFFIC, an organization devoted to fighting illegal wildlife crime. No one knows exactly how big the illegal trade in pangolins has become, but it is undeniably massive and entirely unsustainable. "Since 2000, a minimum of tens of thousands of animals have been traded in each year internationally, from countries ranging from Pakistan to Indonesia in Asia and from Zimbabwe to Guinea in Africa," says Dan Challender, chair of the pangolin specialist group with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the global authority on the status of threatened species. [Source: Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com, February 11, 2013 -]

International trade in pangolins has been banned by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) since 2000; in addition pangolins are listed as a 'protected species' in every Asian home state, except Brunei. Still the trade—wholly condemned by the law both internationally and nationally—has only increased. Pangolin trafficking used to only be confined to Asia, but now Africa has begun trafficking scales to Asia. This is happening in extremely large quantities; tens of thousands of pangolins are impacted each year. In 2010, TRAFFIC released a report that estimated that one criminal syndicate in the Malaysian state of Sabah was responsible for taking 22,000 pangolins over 18 months. Meanwhile in 2011 it was estimated that 40,000-60,000 pangolins were stolen from the wild in Vietnam alone. But total estimates are largely guesses based on seizures of pangolins by law enforcement, which may only represent 10 percent of the total trade. "As the trade is illegal, making any accurate estimates of the size of the trade is impossible," says Shepherd. "It can be said, however, that the trade is great enough that these once widespread and common species have now been all but wiped out completely in many parts of their former range." -

The last stand of the four Asian species has shrunk to Sumatra and Kalimantan in Indonesia, Palawan in the southern Philippines and parts of Malaysia and India. The trade is driven primarily by two countries: Vietnam and China. Notably, these two are also the primary drivers of the illegal trade in rhino horn and play a major role in tiger and ivory trade as well. "Despite China being a party to CITES, the bulk of the pangolins taken from the wilds in Southeast Asia have illegally entered into China unchecked," says Shepherd.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PANGOLINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, TAXONOMY, UNIQUENESS factsanddetails.com

PANGOLIN SPECIES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

INDIAN PANGOLINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED PANGOLINS: CHINESE MEDICINE, MEAT AND EFFORTS TO HELP THEM factsanddetails.com

ILLEGAL ANIMAL TRADE factsanddetails.com;

ILLEGAL ANIMAL TRADE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com;

COMBATING THE ILLEGAL ANIMAL TRADE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Global Trade of Pangolins: Uncovering the Extent and Impact of Illegal Trafficking: Silent Victims of Greed: the Shocking Truth Behind the Illicit Pangolin Trade” by Steve Jordan Amazon.com; “Tiger Bone & Rhino Horn: The Destruction of Wildlife for Traditional Chinese Medicine” by Richard Ellis Amazon.com ; “Illicit Trade The Illegal Wildlife Trade in Southeast Asia Institutional Capacities in Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam” by OECD Amazon.com; “The Illegal Wildlife Trade in China: Understanding The Distribution Networks” by Rebecca W. Y. Wong Amazon.com; “Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade” by Julian Rademeyer Amazon.com; “International Illegal Trade in Wildlife: Threats and U.S. Policy” by Liana Sun Wyler and Pervase Sheikh Amazon.com; “Is CITES Protecting Wildlife?” by Tanya Wyatt Amazon.com “Security and Conservation: The Politics of the Illegal Wildlife Trade” by Rosaleen Duffy Amazon.com; “Strange Foods: Bush Meat, Bats, and Butterflies: An Epicurean Adventure Around the World” by Jerry Hopkins and Michael Freeman Amazon.com; “Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China” by Fuchsia Dunlop and Bee Wilson Amazon.com;

Pangolin Trade in Asia

pangolin scale armor from 19th century India

Denis D. Gray of Associated Press wrote: “ Conservationists first took serious notice of the pangolin trade in the 1990s when massive harvesting in China and its borderlands, driven by skyrocketing prices, was sweeping southwards, decimating the slow-breeding animals in Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. "In many places, hunters tell us they don't even look for them any more," Shepherd says. On why they were harvested to begin with Crawford Allan, senior director of the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC at World Wildlife Fund, said “Anything that is really rare and exotic is desirable. It’s a symbol of wealth, anything seen to be delicacy is now in vogue." [Source: Lulu Morris, National Geographic, May 9, 2017; Denis D. Gray, Associated Press, September 14, 2011]

By the early 2000s, supplies in Thailand were drying up, as evidenced by the development of an unusual barter trade: Thai smugglers would give insurgents in Indonesia's Aceh province up to five AK-47 rifles in exchange for one pangolin, according to the International Crisis Group, which monitors conflicts globally.

The pangolin trade resembles a pyramid. At the base are poor rural hunters, including workers on Indonesia's vast palm oil plantations. They use dogs or smoke to flush the pangolins out or shake the solitary, nocturnal animals from trees in often protected forests."Everything is against them. ... They have no teeth. Their only defense is to roll up in a ball that fits perfectly into a bag," Shepherd says. Middlemen set up buying stations in rural areas and deliver the animals through secretive networks to the less than dozen kingpins in Asia suspected of handling the international connections. Factories in Sumatra butcher the pangolins, slitting their throats, then stripping off and drying the valuable scales.

The smuggling routes almost all end in China, Shepherd says. Other destinations include Vietnam, the top wildlife consuming nation in Southeast Asia, and South Korea. Pangolins from Indonesia are sent to mainland Southeast Asia, then trucked up the Thai-Malaysian peninsula through Thailand and Laos to southern China. Chinese fishing boats ferry those from the Philippines directly to home ports. Smugglers in the eastern Malaysian state of Sabah ship theirs to Vietnam's seaport of Haiphong or to mainland Malaysia to join the trucking routes. From India, they pass overland through Nepal and Myanmar.

Demand for Pangolins

According to the New York Times: In Vietnam, many see pangolin meat as a luxury that conveys social status and health benefits, according to a survey conducted by WildAid in 2015. In China, about 70 percent of people surveyed by WildAid believed that the pangolin could cure ailments ranging from rheumatism to skin diseases; consumers often drink it in wine or in powder form as part of traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions. [Source: Tiffany May, New York Times, April 8, 2019]

According to the Los Angeles Times: Though not a significant consumer of pangolin products, the U.S. is not immune to illicit trafficking of the animal. Statistics confirmed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service show that 30,000 products made from pangolins were seized coming into the U.S. between 2005 and 2015. An agency spokesperson said the products were predominantly “manufactured medicinal items that are labeled to contain pangolin as an ingredient,” but the import of such products is illegal without a permit. [Source: Anne M. Simmons, Los Angeles Times, September 1, 2016]

The trade in pangolin parts has a long history: In 1820, King George III of England was presented with a suit of armor made from pangolin scales. Their skins have been used for making shoes and boots. Between 1980 and 1985, 175,000 pangolin hides were imported into the United States, The practice has since been discontinued.

David Quammen wrote in The New Yorker: Although pangolins are hard to find, they must have once seemed endlessly abundant. Between 1975 and 2000, according to the German biologist Sarah Heinrich and her colleagues, drawing on the database of CITES roughly seven hundred and seventy-six thousand pangolins became merchandise that was traded legally on the international market. That flow of products included almost 613,000 pangolin skins, exported from countries including Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand.[Source: David Quammen, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020]

“There’s a lot of finger-pointing at other cultures,” Heinrich said recently from her home near Potsdam. The finger could point in many directions. Most of the pangolin skins exported between 1975 and 2000 went to North America, where they were turned into handbags, belts, wallets, and fancy cowboy boots. Pangolin leather was especially prized because the animal’s skin bears an eye-catching, almost reptilian, diamond-grid pattern. The Lucchese boot company, bootmaker to Lyndon Johnson, among others, produced pangolin-leather boots before 2000, when cites set the export quota for wild-caught Asian pangolins to zero, essentially making the international commerce illegal.

Hunting and Poaching Pangolins

range of Chinese pangolin

Poachers range from independent trappers to crime syndicates. When a pangolin is afraid it rolls itself into a ball, protecting its soft belly with its armor of scales. It’s good defense against a tiger or a leopard, but it’s about the worst thing to do when confronted with a poacher, who can pick up the animal with with bare hands. It is said that when pagolins do this hunters use machetes to kill them.[Source: Rachael Bale, National Geographic, June 2019]

Jeremy Hance of mongabay.com wrote: “Given that pangolins are nocturnal, small, burrowing, and rarely seen, hunters have had to devise ingenious methods, some used for centuries, to collect the mammals. "Poachers often use dogs to seek out pangolins, especially in areas where pangolin populations have already be reduced," says Shepherd. "Seasoned poachers, however, are very skilled in finding these animals, with some claiming to be able to find them by scent!" [Source: Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com, February 11, 2013 -]

Pangolins are sometimes caught in snares meant for other animals. In the Cardamom Mountains in Cambodia, they often arrive at a rescue center there with severed limbs from poachers’ snares or bites from hunting dogs.The EDGE program says that in northern China, pangolins are usually caught after emerging from winter burrowing. When bought at the market the pangolins "are then killed by crushing the skull, after which the tongue is quickly cut and bled so the warm blood can be drunk as a tonic."

Trading and Selling Poached Pangolins

Jeremy Hance of mongabay.com wrote: “Once caught pangolins are sometimes kept alive until sold. Living conditions can be harsh. Recently it has been reported by Cota-Larson's Project Pangolin that the animals are often force-fed starches in order to rapidly increase their weight. "The procedure must be done carefully and skillfully because if the spout is inserted incorrectly, into the windpipe for example, the starch could kill the pangolin instantly," according to Education for Nature-Vietnam. TRAFFIC has also reported that starches are injected under the skin of pangolins in order to -fatten them up artificially. - [Source: Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com, February 11, 2013 -]

“Pangolin trading comes in many different sizes and methods. says Ambika Khatiwada, who is studying the Chinese pangolin in Nepal. Khatiwada tells the story of how an illegal trader enlisted a local community into catching pangolins for him. "One trader in Nangkholyang village [arrived pretending to be a] simple businessman to sell women's [cosmetics] and started talking innocently about pangolin scales. He motivated the villagers to collect pangolin scales ensuring incentives in monetary form. Ultimately, he was able to collect about 15-20 kilogram of pangolin scales from the village," says Khatiwada, who heard the story from an anonymous source. "This scenario reflects the serious threat to pangolin for its long-term survival in its natural habitat." Where those scales ended up no one knows. But just last year, Nepalese officials arrested a man passing into China with 50 kilograms of scales. "There may be more cases of illegal trade but we don’t have sufficient information," Khatiwada notes. -

“Hard data on the pangolin trade is, like the pangolin itself, elusive. No one really knows how many pangolins are left nor how many exactly are being traded. But Shepherd says we don't need such data, to know that the trade is beginning to take a worrisome toll on some species. "A few years ago seizures of 15-20 tonnes were being made by authorities, but more recently seizures typically involve less than 100 animals. This, and anecdotal information from traders and hunters, strongly suggests that pangolins in Asia are in very serious trouble. Any animal that reproduces as slowly as pangolins do will not be able to withstand such extreme harvest pressures." -

Seizures of Tons of Pangolin Scales

pangolin defending itself from lions

Customs officers seize tons of pangolins and pangolin scales each year. Sometimes the animals are alive. Sometimes there're dead, stripped of scales and frozen gray. The scales are often disguised as other goods and are concealed in sacks or boxes within shipping containers, labelled as oyster shells, cashews, or scrap plastic. In January 2015, officials in Uganda seized two tons of pangolin skins packed in boxes identified as communications equipment. In France in the early 2010s, more than 200 pounds of pangolin scales were discovered buried in bags of dog biscuits. [Source: Erica Goode, New York Times, March 30, 2015; David Quammen, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020]

In November 2024, Indonesian authorities said they seized 1.2 tons of scales from at least 5.900 dead pangolins, worth $1.3 million in Asahan district of North Sumatra province and apparently were meant to be sent to China via Malaysia and Singapore. Associated Press reported: Four suspects, including three army members, were found with some of the scales and were charged with illegal possession of carcasses of protected animals. The four men, if found guilty, face up to 20 years in prison and $314,000 in fines. Indonesian authorities foiled eight plots to smuggle pangolin or its scales in 2024, mostly on Sumatra island. [Source Binsar Bakkara and Niniek Karmini, Associated Press, November 26, 2024]

In August 2023, Thai authorities seized more than a ton of pangolin scales worth over $1.4 million that are believed to have been headed out of the country through a land border. The were found in the northeastern province of Kalasin, and apparently were meant to be transported out through Mukdahan province, which shares a border with Laos, Thai police said. Associated Press reported: Two male suspects, who were on a truck with the scales, were arrested and charged with the illegal possession of carcasses of protected animals. The pangolin scales, which have an estimated price of around 40,000 baht ($1,129) per kilogram, are suspected to have been brought from Malaysia to Thailand, to be transported to Laos and then to China. [Source: Associated Press, August 17, 2023]

In December 2019, Vietnam seized two tonnes of ivory and pangolin scales hidden inside wooden boxes shipped from Nigeria. AFP reported: “Authorities in northern Hai Phong city found 330 kilograms (730 pounds) of ivory and 1.7 tonnes of pangolin scales after checking three container shipments from Nigeria, according to Hai Quan Online, the official mouthpiece of Vietnam's customs department. “The manifest listed the goods as high-end lumber, the online site said, adding that the haul was hidden in boxes at the back of the containers. Published photos showed a rectangular wooden box full of pangolin scales, with elephant tusks mixed in. [Source: AFP, December 24, 2019]

“In May 2019, Vietnamese police found 5.3 tonnes of pangolin scales hidden in a shipment from Nigeria at a southern port. Some two months later in July, authorities in Singapore seized nearly nine tonnes of ivory and a huge stash of pangolin scales destined for Vietnam. During the same month dozens of live pangolins smuggled from Laos were discovered dehydrated and weak on a bus in a central region of the country. In 2017 China intercepted a shipment from Africa of 13 tons of scales (about 30,000 pangolins).

Fourteen Tons of Pangolin Scales Seized in Singapore

In April 2019, in what conservation specialists described as the largest seizure of its kind, more than 14.2 tons of pangolin scales were sezed in Singapore. Approximately 36,000 pangolins were believed to have been killed for the shipment, according to Paul Thomson, an official with the Pangolin Specialist Group, an organization belonging to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. [Source: Tiffany May, New York Times, April 8, 2019]

“The news of this record-shattering seizure is deeply alarming and underscores the fact that pangolins are facing a crisis,” Mr. Thomson said of the seizure. “If we don’t stop the illegal wildlife trade, pangolins face the risk of going extinct.” Singaporean customs officials and the country’s national parks board said the scales, which had been shipped from Nigeria, were headed to Vietnam, home to the second-most lucrative black market for pangolin scales, after China. When Singaporean officials intercepted the pangolin scale shipment, they also found nearly 400 pounds of carved ivory

Seizures of Tons of Pangolin Scales in Hong Kong

In January 2019, officials in Hong Kong said they had intercepted a shipment of nine tons of pangolin scales along with a thousand elephant tusks. They were found hidden under slabs of frozen meat on a cargo ship that had stopped in Hong Kong on its way to Vietnam from Nigeria, said officials, who estimated the shipment’s value at nearly $8 million. Hong Kong officials estimated that the intercepted scales had come from nearly 14,000 pangolins. In 2018 Hong Kong confiscated almost twice as many pangolin scales, by volume, as it had in 2017. [Source: Tiffany May, New York Times, February 1, 2019]

The New York Times reported: “Officials said the 39-year-old owner of a Hong Kong trading company and his 29-year-old employee had been arrested in connection with the seizure. Under Hong Kong law, smuggling illegal wildlife products is punishable by up to ten years in prison and fines of up to $1.3 million. “Customs have done a great job,” said Alex Hofford, a wildlife campaigner for WildAid. “However, we want the Hong Kong government to take a step further. At the moment, they’re just catching the mules, the people who collect the containers — not the people at the top of the pyramid.” He urged the authorities to let investigators follow large consignments to their destinations and track the smugglers’ finances. Hong Kong has long been a port of entry for illegal wildlife products, including elephant tusks and rhino horns. In 2018, lawmakers voted last year to ban all ivory sales by 2021, bowing to pressure from environmental activists.

More than 11,000 pangolins were trafficked in a three month period in 2016, according to data collected by the , according to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). For example, In June, authorities in Hong Kong confiscated 4.4 tons of pangolin scales hidden in cargo labeled “sliced plastics” from Cameroon. The haul was estimated to involve between 1,100 and 6,600 African pangolins, and was valued at around $1.25 million on the black market IUCN Director General Inger Andersen said it was one of the largest seizures of pangolin scales, In July Hong Kong officials seized more than 10 tons of pangolin scales in shipping containers coming from Nigeria and Ghana. In August, Indonesian authorities confiscated more than 650 pangolin bodies hidden in freezers at a home on the island of Java, according to media reports. [Source: Anne M. Simmons, Los Angeles Times, September 1, 2016]

Seizures of Tons of Pangolin Meat

In February 2019, 33 tons of pangolin meat were seized in two processing facilities in Malaysia, according to Traffic, a wildlife conservation group. [Source: Tiffany May, New York Times, April 8, 2019]

In 2011, eight tons of pangolin meat and scales were found in the boxes at Jakarta airport and at a warehouse raided the following day. Four people were arrested. Denis D. Gray of Associated Press wrote: “As the 20 cardboard boxes bound for China rolled through the X-ray machine at Jakarta's airport, Indonesian customs officials suspected what was inside didn't match what was declared. Instead of fresh fish, a closer look revealed the meat and scales of the most illegally trafficked mammal in Asia: the pangolin.” "I am trying hard to win the war," says Brig. Gen. Raffles Brotestes Panjaitan, Indonesia's top wildlife police officer, citing the July seizure. But he lists a host of obstacles: poverty, corruption, an inadequate force and weak international cooperation. [Source: Denis D. Gray, Associated Press, September 14, 2011]

In April 2013, a Chinese boat filled with 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) of pangolin meat ran into a coral reef in the southwestern Philippines. Teresa Cerojano of Associated Press wrote; The steel-hulled vessel hit an atoll at the Tubbataha National Marine Park off Palawan island. Coast guard spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Armand Balilo said that 400 boxes, each containing 25 to 30 kilograms of frozen pangolins, were discovered during a second inspection of the boat. [Source: Teresa Cerojano, Associated Press, April 15, 2013]

The World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines said the Chinese vessel F/N Min Long Yu could have been carrying up to 2,000 of the toothless, insect-eating animals rolled up in the boxes, with their scales already removed. "It is bad enough that the Chinese have illegally entered our seas, navigated without boat papers and crashed recklessly into a national marine park and World Heritage Site," said WWF-Philippines chief executive officer Jose Ma. Lorenzo Tan. "It is simply deplorable that they appear to be posing as fishermen to trade in illegal wildlife."

The boat's 12 Chinese crewmen are being detained on charges of poaching and attempted bribery, said Adelina Villena, the marine park's lawyer. She said more charges are being prepared against them, including damaging the corals and violating the country's wildlife law for being found in possession of the pangolin meat. It is not yet clear which of the four Asian pangolin species the meat comes from. The International Union of Conservation of Nature lists two as endangered: the Sunda, or Malayan, pangolin, and the Chinese pangolin. Two others, including the Philippine pangolin endemic to Palawan, are classified as near threatened.

Alex Marcaida, an officer of the government's Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, Philippine authorities consider the Philippine pangolin threatened because of unabated illicit trade. He said the Chinese crewmen have said the pangolins came from Indonesia, but officials were still verifying the claim. The Philippine military quoted the fishermen as saying they accidentally wandered into Philippine waters from Malaysia. They were being detained in southwestern Puerto Princesa city, where Chinese consular officials visited them. The fishermen face up to 12 years' imprisonment and fines of up to $300,000 for the poaching charge alone. For possession of the pangolin meat, they can be imprisoned up to six years and fined, Villena said.

African Pangolins and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

In recent years, Africa has become a major source of pangolins and pangolin body parts. African pangolins, comprising four species, have been hunted locally for bushmeat and medicine for a long time. Two African species are listed as endangered and the other two are listed as vulnerable as a result over-hunting locally and Asian pangolin trade.

David Quammen wrote in The New Yorker: “Since early times, many peoples of sub-Saharan Africa have “harvested” pangolins, trapping the animals with snares, tracking them with dogs, or coming across them in the forest. The hunters traditionally consumed their catch or sold it into local bush-meat markets. Eventually, the meat became popular in cities, too, such as Libreville, in Gabon, and Yaoundé, in Cameroon, and that led to rising prices around the start of the twenty-first century. [Source: David Quammen, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020]

Rachael Bale wrote in National Geographic: ““Pangolins are eaten as bushmeat in western and central Africa and by some indigenous groups in South and Southeast Asia. Their parts also are used in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa as traditional medicine. Pangolins are not hard to find in Cameroon. They’re for sale at outdoor bushmeat markets, where they lie dead next to monkeys and pythons on folding tables. They’re for sale on the sides of the roads, where vendors hold them upside down by the tails for passing drivers to see. They’re a common enough sight for you to think: None of these people seem to be having trouble finding pangolins, so how close to extinction can they be? [Source: Rachael Bale, National Geographic, June 2019]

Africa and and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

At least 67 countries and territories on six continents have been involved in the pangolin trade, but the shipments with the biggest quantities of scales have originated in Cameroon, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Uganda, according to an analysis by Traffic. And they’ve mainly been heading to China. In the last decade, there’s been a massive growth in intercontinental trade in pangolins, especially their scales,” says Challender. This shift means that Asian pangolins are becoming difficult to find but that the value of scales makes it worth the extra cost to smuggle pangolins from Africa to Asia.[Source: Rachael Bale, National Geographic, June 2019]

David Quammen wrote in The New Yorker: “As the Asian populations declined, African pangolins began flowing east in large quantities. The scales mostly moved through the ports and airports of Nigeria and Cameroon to Asia, especially China and Vietnam. “I know we’re serving as a transit point,” Olajumoke Morenikeji told me recently. She’s a zoologist, and a founder of the Pangolin Conservation Guild Nigeria. To judge from the thousands of kilograms of scales seized, she said, “you can’t have all that just coming from Nigeria.”[Source: David Quammen, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020]

“Luc Evouna Embolo, an officer for traffic, an international network that monitors the wildlife trade, gave a similar account from Yaoundé. Increasingly, middlemen incite local people to collect pangolins from the field and sell to them. The middlemen sell to urban businessmen who illegally export the animals. A villager might get paid three thousand C.F.A. francs (roughly five dollars) for a pangolin that will be worth thirty dollars in Douala, Cameroon’s economic capital, and much more in China. In 2017, police made one seizure amounting to more than five tons of scales, for which two Chinese traffickers were arrested.

Rachael Bale wrote in National Geographic: ““Right after I left Cameroon, police and wildlife officials intercepted a shipment of pangolin scales and arrested six people. The pangolin scales had arrived by truck from the Central African Republic, where it’s likely that traffickers had amassed them from many smaller-scale traders there, as well as from traders in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The plan, said Eric Kaba Tah, of Last Great Ape, was to drive the shipment to Douala, where the smugglers would sell it up a level on the supply chain. Often, the next destination for the scales would be Nigeria, Tah said, then on to China, Malaysia, or Vietnam. “More and more we are seeing wildlife products leave the central African subregion, passing through Cameroon to Nigeria, where traffickers believe wildlife law enforcement is not as strong,” Tah said.

“It helps traffickers that Africa-to-Asia smuggling routes already exist for other wildlife products. Shipments of pangolin scales have been discovered alongside ivory, hippo teeth, and other illicit animal parts.The organized criminal networks that move ivory also move pangolin scales, according to the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based research group that focuses on illicit networks, including organized wildlife crime. Such crimes are typically associated with money laundering, tax fraud, illegal arms possession, and other offenses.

Efforts to Crack on the Illegal Pangolin Trade

Pangolins are protected in many Asian nations and the international trade in the four species of Asian pangolins has been prohibited since 2000. In 2017 a ban on international commercial trade in all eight species went into effect, voted in place by the 183 governments that are party to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), the treaty that regulates cross-border trade in wild animals and their parts. [Source: Rachael Bale, National Geographic, June 2019]

"Sentencing to the full extent of the law" is also needed, according to Cota-Larson. Preservation efforts focus on strengthening often lackluster law enforcement in the region. "Everything is now set up to stop this from happening. The laws are good enough to put traders out of business and into jail," Shepherd says. "It boils down to corruption and enforcement agencies not having the will to act. Wildlife trafficking is still generally not taken seriously." [Source: Denis D. Gray, Associated Press, September 14, 2011]

In 2016, a coalition of conservation groups passed a motion calling for all eight pangolin species to receive the most stringent international protection available, a move that essentially would ban all international commercial trade and ramp up enforcement. "Saving pangolins is going to require a multi-pronged approach," says Shepherd. "Governments need to commit to increasing enforcement efforts to shut the trade down at all links along the chain. Poachers, middlemen, and large-scale traders. Penalties should be severe enough to serve as effective deterrents." Like many other species falling into the illegal wildlife trade trap, Shepherd and other experts suggest a mix of stepping-up law enforcement efforts and working on stemming demand. -

Obstacles to Cracking Down on the Illegal Pangolin Trade

Most countries have laws against hunting pangolins. But enforcement is often weak, and the incentive for local poachers in poor rural areas to catch and sell pangolins and other wildlife to middlemen for smuggling organizations is strong, Bunra Seng, Conservation International’s director in Cambodia, told the New York Times. [Source: Erica Goode, New York Times, March 30, 2015]

Jeremy Hance wrote on mongabay.com: Poachers and traders are often let go with more than a slap-on-the-wrist even in countries where laws are strong. This is starting to change for more well-known animals—such as tigers and rhinos—but pangolin dealers are still getting away with it. "Pangolin traders continue to operate with very little fear of serious penalties. Most pangolin traders that are caught have the animals confiscated, but do not receive a penalty that will sever as a deterrent. Many are not convicted at all. If enforcement efforts were sufficient, pangolins would not be in the critical state they are in now," explains Shepherd. [Source: Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com, February 11, 2013 -]

According to Associated Press: Weighed against the profits, the penalties for trafficking are low. Not long ago, an entire pangolin could be bought in Indonesia for $5 or less. Panjaitan, the Indonesian official, says just the scales from an average-sized animal now go for about $275. The scales fetch up to $750 a kilogram ($340 a pound) in China.Panjaitan, the director of Investigation and Forest Protection in the Ministry of Forestry, hopes Indonesia will greatly stiffen its jail term this year for major forest encroachment - directly linked to harvesting of pangolins and other wildlife - to a maximum of 20 years. [Source: Denis D. Gray, Associated Press, September 14, 2011]

Although seizures and arrests of low-level smugglers have increased substantially, almost none of the major players have been put behind bars. And as Asian stocks vanish, Africa's three pangolin species have emerged as substitutes - a similar pattern to other traditional Chinese medicines, such as subbing lion bones for those of the now rare tiger.

Still, Steven Galster, executive director of Bangkok-based FREELAND, a group fighting wildlife and human trafficking, points to some progress. Suspecting that a private zoo was a cover for wildlife trafficking, Thai officials charged Daoruang Kongpitakin in July with illegal possession of two leopards. Her brother and sister had been arrested several times for pangolin smuggling.

Wildlife investigators are also tracking a shadowy company in Southeast Asia, which wields influence with both senior Lao and Vietnamese officials and could be among the region's biggest traffickers. ASEAN-WEN, a wildlife enforcement network of the 10 Southeast Asian nations, has also notched successes since its 2005 inception. Such developments across several countries could be a game changer, Galster says. "But will they move fast enough for the species to survive?"

Did Trafficked Pangolin Cause the Coronavirus Pandemic?

Pangolins are susceptible to coronaviruses like humans and some believe they may have played a role in emergence of SARS and Covid-19 in humans, perhaps by serving as an intermediary between Covid-19-carrying bats and humans. David Quammen wrote in The New Yorker: Sampling of tissues from dead pangolins has shown that some carry viruses very similar to sars-CoV-2. Did a population of these animals serve as intermediate hosts, within which a bat virus lived briefly — or maybe for some decades, acquiring adaptations that could make it devastating to humans? The evidence is complicated.[Source: David Quammen, The New Yorker, August 24, 2020]

There was an unheeded signal nine months before th coronavirus outbreak began. On March 24, 2019, the Guangdong Wildlife Rescue Center, in Guangzhou, took custody of twenty-one live Sunda pangolins that had been seized by customs police. Most of the animals were in bad health, with skin eruptions and in respiratory distress; sixteen died. Necropsies showed a pattern of swollen lungs containing frothy fluid, and in some cases a swollen liver and spleen. A trio of scientists based at a Guangzhou governmental laboratory and at the Guangzhou Zoo, led by Jin-Ping Chen, took tissue samples from eleven of the animals and searched for genomic evidence of viruses. They found signs of Sendai virus, harmless to people but known for causing illness in rodents. They also found fragments of coronaviruses. Still, this was not big news when the Chen group published its report, on October 24th. The scientists noted that either Sendai or a coronavirus might have killed these pangolins, that further study could help with pangolin conservation, and that such viruses might be capable of crossing into other mammals.

“Three months later, the word “coronavirus” carried a different ring. An initial small cluster of “abnormal pneumonia” cases had appeared in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province; soon the number had exploded to thousands, and the city was in lockdown; Chinese sources had revealed that a “novel coronavirus” was the cause of this disease...Scientists who understand zoonotic diseases — the diseases caused by pathogens that pass from nonhuman animals into humans — had begun asking, Which animal was the source? Everything comes from somewhere, and novel viruses come to people from wildlife, sometimes through an intermediary animal that may or may not be wild.

“Bats were prime suspects, because the sars virus that surfaced in 2002 — highly lethal and transmissible, but quickly contained by the middle of 2003 — had been a coronavirus hosted by bats. The mers virus, which emerged on the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, even more lethal but less transmissible than sars-CoV (as that first virus became known), was also a coronavirus traceable to bats. On February 7th, 2020, the president of South China Agricultural University (South China Ag.) in Guangzhou, declared that a team from her institution had found what may be an intermediate host of the virus, bridging the gap between bats and humans: pangolins. According to a report by Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency, the pangolin virus that the researchers had investigated was a ninety-nine-per-cent match with the coronavirus showing up in people. The announcement was an overstatement of what the researchers had found, but it caused a flurry of headlines. Even the cites secretariat, based in Geneva, echoed the claim, tweeting the next day that “Pangolins may have spread coronavirus to humans,” and sugaring that sour tweet with video footage of cute pangolins.

The implication was: these adorable animals carry lethal viruses, so best to leave them alone. When the study from South China Ag. went online, the big result was not quite as big as advertised, though it was still dramatic. The coronavirus genome that these researchers had assembled, from pangolin lung-tissue samples, contained some gene regions that were ninety-nine per cent similar to equivalent parts of the sars-CoV-2 genome — but the over-all match wasn’t that close. Maybe two coronaviruses had merged in a single animal, the researchers wrote, and swapped sections of their genomes — a “recombination event.” Such an event may even have proved fateful, by patching one genomic section of a pangolin coronavirus together with a bat coronavirus. That section, known as the receptor binding domain (R.B.D.), endowed the composite virus with an extraordinary capacity to seize and infect certain human cells, including some in the respiratory tract.

“The South China Ag. team got its samples from pangolins at the Guangdong rescue center, some of which had previously been sampled by Jin-Ping Chen’s group. The team’s study, of which Yongyi Shen was a senior author, gave vividness to a technical report when it noted that the rescued pangolins “gradually showed signs of respiratory disease, including shortness of breath, emaciation, lack of appetite, inactivity, and crying.” Pangolins are sensitive, hard to keep alive in captivity even under solicitous care; the harsh conditions of being trafficked internationally would make them especially susceptible to infection. But what killed those sixteen pangolins? Was it Sendai virus, or a coronavirus, or some other cause unrelated to concerns about human health? We’ll probably never know. Later in the paper, buried in a section on methodology, Shen and his co-authors added that the animals “were mostly inactive and sobbing, and eventually died in custody despite exhausting rescue efforts.” Sobbing might be taken as a metaphor for respiratory struggle, but, then again, sometimes a sob is just a sob.

At least three more scientific papers on the subject appeared between February and May, two from Chinese teams and one from a group at the Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston. All three based their analyses, as had Yongyi Shen’s group at South China Ag., on genomic data from pangolins at the rescue center in Guangdong. One group reported that pangolins seem to carry a coronavirus so similar to sars-CoV-2 that it might be the source of the pandemic. Part of their evidence was that crucial section of the pangolin coronavirus genome, the receptor binding domain, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the R.B.D. in the pandemic virus. Another group said, No, our analyses do not support the idea that the pandemic virus came directly from a pangolin. The third group, posting their report as a preprint, before peer review, agreed with Yongyi Shen: this sars virus looks as though it could be the result of a recombination event — a switching of genome segments in the body of one animal — or maybe several such events, accidentally combining genes from bat viruses, pangolin viruses, and even other viruses to become the extremely well-adapted virus causing the nightmare of covid-19.

“There’s also a possibility that the viruses carried by smuggled pangolins do not reflect the typical viral burden of wild pangolins. They might not really be pangolin viruses at all, but infections acquired from other wild animals under the conditions of the trafficking chain — stress caused by shortage of food and water and oxygen, human handling, temperatures too hot or too cold, close confinement in cages adjacent to various doomed creatures. That could explain the respiratory symptoms: pangolins, unlike bats, may be unaccustomed to these viruses. One group of scientists looked at pangolins near the supply end of the trade flowing toward China, collecting throat and rectal swabs from three hundred and thirty-four Sunda pangolins in Peninsular Malaysia and the state of Sabah (Malaysian Borneo) that had either been seized from smugglers, or otherwise rescued, between 2009 and 2019. Not one sample tested positive for a coronavirus.

Still another paper, published this spring by Nature, examined samples from a different batch of rescued pangolins — from Guangxi Province — as well as genomic evidence from the much studied Guangdong pangolins. These scientists found two distinct lineages of coronavirus closely related to sars-CoV-2. Two coronaviruses, both resembling our nemesis bug? It seemed to suggest that pangolins are brimming with invisible menace. The first author on the Nature paper was Tommy Tsan-Yuk Lam; the senior author was a famed virus hunter in Hong Kong, Yi Guan; and among the other authors was Edward C. Holmes, who brokered the release of the first sars-CoV-2 genome.

Lam explained that he and Guan had obtained viral genome sequences from pangolins confiscated by customs authorities in two different provinces — not just the rescue-center ones but also some seized during 2017 and 2018 in Guangxi Province, which shares a border with Vietnam and therefore lies along a pangolin-trafficking route. Two things were notable about the animals, Lam told Holmes: “They’ve got this respiratory disease. And guess what. They’ve got, like, this coronavirus in them.” Another coronavirus, not a familiar one, but also resembling sars-CoV-2. Holmes told me, “I thought, Well, that’s extraordinary.”

“Edward C. Holmes is a brilliant evolutionary biologist, the author of an authoritative book, from 2009, titled “The Evolution and Emergence of RNA Viruses” (they are the fastest-evolving and most dangerous kinds of virus, and include the coronaviruses). Holmes signed on to assist with his specialty, analyzing genomic data. What surprised him was not just that two distinct groups of pangolins both carried coronavirus infections, or that both viruses were similar to the human virus, but that they were distinct from each other. “That’s what is so striking,” he said. “There are two lineages, and the Guangdong ones are closer to sars-CoV-2 than the Guangxi ones. But they’re both close. Right? So it’s not that there’s one outbreak in pangolins.” Two distinct coronaviruses, each similar to sars-CoV-2, one with a receptor binding domain to which human-lung cells are highly susceptible, had travelled into southern China in smuggled pangolins. “What are the odds?” Holmes said. The odds are low. The finding suggests, he added, that there are many more dangerous viruses lurking in pangolins than we have detected so far.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, CNN, BBC, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2025