NORWAY LEMMINGS

Norway lemmings (Lemmus lemmus) and plump, mouse-sized creatures with thick brown fur patterned with black and orange. Also known as Norwegian lemmings, they live primarily in the tundra and birch woods of the Scandinavian mountains and are famous for their boom-and-bust population fluctuations, migrations and purportedly for following a leader and leaping en masse off cliffs, something which is not true. Lemmings are small rodents, usually found in or near the Arctic in tundra biomes. They form the subfamily Arvicolinae (also known as Microtinae) together with voles and muskrats, which in turn is part of the superfamily Muroidea, which also includes rats, mice, hamsters and gerbils. Lemmus species generally live for one to two years. The oldest recorded Norway lemming was a specimen in captivity which lived for 3.3 years.

A common species of lemming, Norway lemmings are found in northern Fennoscandia (Scandinavia and the Karelia part of Russia), where they are the only vertebrate species endemic to the region. These lemmings are active both day and night, alternating naps with periods of activity. They dwells in tundra and fells, and prefers to live near water. Adults feed primarily on sedges, grasses and moss. By some reckonings, Fennoscandia, where Norway lemmings live, stretches from the Russian Kola Peninsula in the east to the west coast of Norway in the west and from the northern coast of Norway south to the Baltic Sea. However, Norway lemmings may migrate further south than that during on of their population booms.

Norway lemmings are found in tundra and alpine regions. During the winter they live in insulated spaces under the snow, which them with warmth, shelter, access to food, and protection from predators. When there is no snow cover, Norway lemmings live in a variety of mainly wetlands habitats, including bog and marshes. They also make their home in areas where dwarf shrubs are the main vegetation. Norway lemmings seek safety and shelter in shallow underground spaces which may be burrows they dig themselves or burrows already dug by another animal or an already existing underground space. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Norway lemmings are not endangered. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The IUCN says their populations are stable and possible future threats include climate change and grazing of other herbivores which reduces lemming habitat.

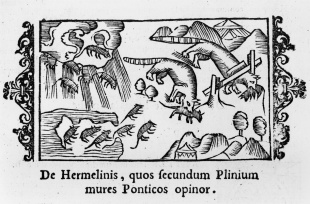

Norway lemmings have been useful to scientists who study population. The population cycles of Norway lemmings provide a foundation for understanding population dynamics and their impacts on vegetation growth, predator-prey relationships and environments changed by climate change. Norway lemming population cycles and migrations have also given birth to a number of myths and legends in Scandinavia. A Swedish Catholic priest named Olaus Magnus was among the first to illustrate lemmings marching across the land. In his Historia de gentibus septentionalibus ("History of the Northern Peoples", 1555) there is woodcut showing scary-looking giant rodents descending from the skies and attacking smaller creatures. Despite such legends, Norway lemmings have relatively little negative impact on human agriculture as they generally live in places humans don’t live and only migrate into more human populated areas during years of high population density, which are generally every three to five years.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LEMMING BOOM-AND-BUST REPRODUCTION AND MYTHS ABOUT MASS SUICIDE factsanddetails.com

LEMMING SPECIES factsanddetails.com

STEPPE LEMMINGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Norway Lemming Characteristics and Diet

Norway lemmings range in weight from 20 to 130 grams (0.7 to 4.6 ounces) and have a head and body length ranging from eight to 17.5 centimeters (3.15 to 6.9 inches). They do not have a noticeable tail. Their average basal metabolic rate is 1.071 cubic centimeters of oxygen per gram per hour. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Norway lemmings have thick bodies with heavy fur coats ideal for maintaining body heat in very cold environments. Their color is black and brown with some golden-yellow streaks. Theit underbelly is a lighter color than the rest of their fur. They retain the same fur color, regardless of season. Their teeth are characteristic of their subfamily — Microtinae — with 12 molars, four incisors, and flattened crowns. Their limbs are short and mostly tucked under the body. The claw of the first digit on each paw is larger and flatter than the rest of the claws. This modification helps lemmings to tunnel through snow.

Norway lemmings are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts). Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, wood, bark, stems, seeds, grains, nuts, bryophytes (mosses) and lichens. They mainly eat mosses, lichens, bark, and some grasses. Mosses thrive when there has been a sufficient amount of snow over the winter. Food may be difficult or dangerous to obtain just before winter when there are rains and freezing temperatures without snow cover.

Norway Lemming Behavior

Norway lemmings are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). Home Range: When populations are low there may be three to 50 Norway lemmings per hectares (1.2 to 20 lemmings per acre), and when the population is high there may be up to 330 lemmings per hectares (134 lemmings per acre). [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Norway lemmings are active during day the night. They spend their waking periods (6 hours on average) foraging and moving about. They live in northern latitudes where there can be up to 24 hours of daylight in the summer and the same with darkness in the winter and thus their periods of activity and inactivity are likely an adaptive response to their environment. During the winter they live in insulated spaces under the snow. This provides them with warmth, shelter, access to food, and protection from predators. Having this shelter gives young lemmings a better chance of survival.

Norway lemmings prefer to live independently of each other, and they can become aggressive toward each other during periods of overcrowding. Male lemmings are known to engage in boxing, wrestling, and threatening behavior. Their independent nature may be one of the driving factors in dispersal during their population peaks.

Norway Lemming Senses and Communication

Norway lemmings sense and communicate with touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. Voles and lemmings have well-developed senses of smell and hearing. Some lemming species use scents to mark boundaries, and many species of lemmings can recognize members of their own species by their scents. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Voles and lemmings use different calls for distress, aggression, and mating. Each species has a unique set of calls. When they are provoked Norway lemmings can be quite aggrissive. Sandrine Ceurstemont wrote in New Scientist: Don’t mess with this lemming. Its ferocious calls and multicolored fur set it apart from most other small rodents, which are typically docile and drab. Malte Andersson from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden has been testing whether Norway lemmings deter predators by warning them of their aggressive nature with their shrieks. [Source: Sandrine Ceurstemont, New Scientist, February 6, 2015]

The vivid markings on the fur also indicate to predators that this critter isn’t for eating. Having such warning colors — a phenomenon known as aposematism — is common in insects, snakes and frogs, but unusual in herbivorous mammals. This combination of hues made the lemmings easier to spot than their plain-looking neighbors, grey-sided voles.

When a predator, played by humans in Andersson’s test, is far away, these lemmings prefer to go unnoticed, he found. But when predators get closer, to within a few meters, these lemmings were much more likely to give out a warning call than their browner relatives. The conspicuous colors, aggressive calls and threatening postures together let predators know to expect a fight, and potentially damage, if they attempt to eat a Norway lemming. In contrast with the voles, these lemmings aggressively resist attacks by predatory birds.

Norway Lemming Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Norway lemmings are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. |They engage in year-round breeding and females have an estrus cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females. Norway lemmings can produce a litter every three to four weeks. The average gestation period is 16 to 19 days. The number of offspring ranges from five to 13, with the average number of offspring being seven. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity between two to four weeks; males do so at four to six weeks. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Norway lemmings generally live independently of each other but they do come in contact for mating. David Attenborough wrote: “In any population there are more females than males and it is they that form the stable social groups — mother, sisters, daughters and granddaughters, all living together. The males are wanderers. One of them will venture down a tunnel to visit these all-female groups but initially he is not welcomed. The females set upon him and bite him so cruelly that he may well retreat. The females thus ensure that the father of their offspring will not only be lustful but strong. If the male is persistent and stoical enough to withstand this onslaught, he is allowed to take up temporary residence. Then he copulates with all the females, one after another.” [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

The reproductive ability of lemming females is truely something to behold. Their gestation period is only sixteen days and they may produce up to a dozen offspring in one birth. The young grow up fast and become sexually mature on only three weeks. “Meanwhile the first female has mated again and will reproduce yet another litter within a month of giving birth to her first. If there is sufficient food and space. She can breed throughout the years. Not surprisingly therefore, as the vegetation on which lemmings live increases through the spring and summer, the population grows rapidly. Even allowing for great losses in the following winter when conditions are harder and food is more difficult to find, the process can not go on indefinitely. After about four or five years, there is not enough food to withstand cropping by such huge numbers and the population suddenly crashes.

Lemmings are known to be aggressive toward one another, especially when they are crowded together. Under such circumstances they have have been observed boxing and wrestling with each other. Other lemming species engage in such behavior as parts of their mating rituals and Norway lemmings may do so as well. Females of the genus Lemmus undergo post-partum estrus, so a female may be receptive to mating shortly after giving birth to a litter and can produce a litter every three to four weeks .

Parental care is provided by females. The birth weight of Lemmus young is 3.3 grams. Time to weaning for this genus is usually 14 to 16 dayss. Because females experience post-partum estrus, they may be pregnant with their next litter while still caring for the young from her previous litter. Lemming and vole mothers are usually very protective of their young and keep their offspring close to them until they become independent..

Norway Lemming Migrations

Norway lemmings have both spring and fall movements. Spring movements are caused by snow melt and last only two or three weeks, whereas fall migrations are density-dependent, and may last two to three months. Such remarkable movements in the fall have not been reported for other lemming species. [Source: barentsinfo.org]

During peaks lemming population disperse beyond their normal range in search of more space and more food. They may even move into the taiga and forests which are not their usual habitat. When there is a lot of them they can eat up the heath shrubs, mosses and lichens that they commonly eat. Generally, the population peaks occur every three to five years. However, some studies have found that the number of years between the peaks have been increasing and peaks are less regular in occurrence. This irregularity is attributed to climate change. With shorter winters, there is less snow cover and lemmings rely on the snow cover during the winter to provide safe access to food and shelter while breeding and raising their young.[Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

While many other rodents experience population peaks, Norway lemmings are the only species that will embark on long distance migrations. The famous mass migrations of the Norway lemmings can temporarily extend their range by 200 kilometers into the boreal forest but they only occur about three times a century.

Norway Lemming Mass Migration

David Attenborough wrote: “Every thirty or forty years or so in the autumn there is a population explosion on an altogether different scale. It’s causes are still not properly understood. Suddenly from the upland forests of Scandinavia, a great tide of lemmings emerges and starts to flow down towards the valleys, advancing by a s much as ten miles a day. The animals invade cultivated fields, destroying the crops. They swarm into gardens and houses, They tumble down wells where their rotting bodies foul the water. In 1970, on a 120-mile stretch of road, 20,000 were killed by cars. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

“The lemmings as they search frantically for food, become very aggressive. Indeed, they are so ferocious that they will attack creatures many time their size — including human beings. Fights may break out between them as they rush wildly onwards, searching for new territory and more food..

“If they reach a river, the pressure of those advancing behind them may force the leaders to take to the water. They are very competent swimmers. Their dense buoyant fur causes them to ride high in the air with their backs fully exposed, so the surface of the water appear to be clotted with them. The animals are able to avoid swimming in circles for they can orientate themselves,

“A migration that took place in northern Finland in 1961 led to the establishment of lemming colonies as far away as the of the Baltic Sea, a hundred miles or so away from their pervious territory, Those colonies flourished for a few years, but such behavior could clearly be important for the survival of a species living in a part of the world where the climate changes consistently over long periods. In recent centuries in the Arctic, glaciers have advanced and retreated, snow fields appeared and disappeared, and land that was once frozen and barren has again become habitable. If such changes become long lasting, the lemmings will be among the first to discern it and so will be able to rapidly take control of new territory.”

Norway lemming migrations have become famous through legends and stories. One common fable is that lemmings set out on these migrations with the intent to committing mass suicide in the sea. Although mass drowning of lemmings do occur on these migrations (it is the number one cause of death on the journey), lemmings are not suicidal. Although lemmings are good swimmers, the sheer number of them and the back ups that occur when obstacles such as rivers are encountered seems to trigger a panic that causes the animals to drown during the crossing. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

See Separate Article: LEMMING BOOM-AND-BUST REPRODUCTION AND MYTHS ABOUT MASS SUICIDE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025