LEMMINGS

Lemmings are small, short-tailed rodents that look like fat, furry mouses. Usually found in or near the Arctic in tundra biomes, they form the subfamily Arvicolinae (also known as Microtinae and sometimes referred to as the meadow mouse family) together with voles and muskrats. Residing in some of the world's coldest places without hibernating, lemmings survive in the summer by eating lichens and mosses and survive the winter by burrowing themselves under the snow. Lemming are 1) Muroidea, a large and complex superfamily of rodents, including mice, rats, voles, hamsters, lemmings, gerbils, and many other relatives, and 2) Cricetidae, a family of rodents within Muroidea. Muroidea includes true hamsters, voles, lemmings, muskrats, and New World rats and mice. At over 870 species, it is either the largest or second-largest family of mammals, and has members throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia.

Arctic lemmings include true lemmings, of the genus Lemmus, and collared lemmings, of the genus Dicrostonyx. Although both have a circumpolar — though not identical — distribution, the two genera differ in many respects. Collared lemmings are much more resistant to extreme low temperatures than true lemmings. Consequently, its distribution extends farther north: collared lemmings are found on the northernmost islands of the Canadian Arctic and in northern Greenland, whereas the range of true lemmings reaches down to the boreal zone and does not include Greenland or the northern Canadian islands. [Source: barentsinfo.org]

True lemmings eat mosses, supplemented by grasses and sedges. Collared lemmings prefer forbs and shrubs like avens and willows. This distinction is reflected in habitat use. In the Arctic tundra, Lemmus is usually found on wet lowlands or moist patches. Dicrostonyx lives almost exclusively on dry and sandy hills and ridges. Most change color in the winter. Eskimos have traditionally used the soft white winter coats of collared lemmings for clothing decoration and toys for the children.

Lemming World: Arctic in the Winter

David Attenborough wrote: “Winter in the Arctic: The forests of fir and spruce are half buried in snow. Their sloping branches are burdened with it. It lies several feet deep all over the ground. The sun, when it comes, appears for only a few brief hours of the day, hanging red and sullen just above the horizon before dunking down and disappearing for another eighteen hours or so. And as it vanished, the bitter cold tightens its grip. There is no sound except for the distant muffled thud as some snow slides off one of the slanting branches to explode in a cloud of powder on the snowdrift beneath. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

“Few places are more hostile to animal life. Amphibians would freeze solid here. Nor can reptiles tolerate such extreme and continuous cold. Further south frogs and salamanders, lizards and snakes take shelter beneath the ground and relapse into torpor, their bodily processes suspended until the arrival of spring months later. But here the winter is so intense they would die,

“Yet there are animals here, A foot down beneath the surface of the a small entirely white creature the size of a pet hamster scurries along a tunnel. It is a collared lemming. It and other members of its family have excavated a complex home within the snow field. It has different kinds of accommodation. Some are sleeping chambers. Others are dinning rooms where the sparse leaves of half-frozen grass still rooted in the earth are exposed and can be cropped. Some of the passage-ways that connect these chambers run along the ground beneath the roof of the snow. Others tunnel their way through the snow itself and lead up to the outside world where one of the family may occasionally go to prospect for any vegetable food — a small seed perhaps — that might have arrived in the upper surface of the snow.

“It cost the lemmings a great deal to survive here. They pay by using some f their precious food to generate heat within their bodies. In order to keep their fuel costs to a minimum they have to conserve as much heat as they can. And they do that by insulating their bodies with fur. It is dense and fine and covers them entirely except for their eyes.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

LEMMING SPECIES factsanddetails.com

NORWAY LEMMINGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

STEPPE LEMMINGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Rapid Lemming Reproduction Rates and Explosive Population Fluctuations

Lemming are very prolific. They can became pregnant at the age of 14 days (more often around two months) and can reproduce five or six liters of 4 to 6 offspring annually. The gestation period is only thee weeks. According to the Guinness Book of Records, one pair produced eight litters in 167 days. Theoretically a single pair of lemmings could produce 10,000 lemmings in a single years, Oredatris and lack of food are the main factors that keep their numbers in check. Frequently the animals over produce to the point they outstrip the food supply.

Lemmings are well-known for their explosive population fluctuations. The causes of these population cycles have long been a topic of research and often heated discussion. Food, predation, and intrinsic physiological factors are possible explanations, each of which has some scientific support. It may well be that in different areas different factors play the critical role. In the Canadian Arctic, for example, the longterm low density of Collared lemmings is explained by heavy predation. In Fennoscandia (Scandinavia and Karelia part of Russia), on the other hand, lemming crashes in alpine areas seem to be caused by shortage of food, but when lemmings migrate into the boreal forests, they are regulated by predation.

Lemming populations surge and crash with a high degree of regularity at intervals of about once every four years. In a very short period the numbers of lemmings dramatically increase and then virtually disappear. In the 1500s, it was seriously suggested that lemming dropped from the sky. No other plausible explanations could be offered as to why their population could increase so much so suddenly.

See Separate Article: NORWAY LEMMINGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Impact of Lemming Population Fluctuations On Arctic Ecosystems

The explosive lemming population fluctuations have a strong impact on the vegetation and affect the nutrient cycle. Shallow permafrost slows down soil processes, but when lemmings at peak densities graze away much of the vegetation cover, the summer thaw can penetrate deeper into the soil, making more nutrients available. Lemmings also have a strong impact on the biomass and species composition of the vegetation. [Source: barentsinfo.org]

Alexandria Stubblefield wrote in Animal Diversity Web: During population peaks, when there are up to 134 lemmings per acre, the damage that Norway lemmings inflict on vegetation can take the area up to four years to recover from. While the effect to the tundra landscape can be negative during these times, the effect on predator populations can be positive. For example, Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) have a higher probability of recolonizing an area when lemmings are abundant and when their competitor,red foxes (Red foxes), do not live in the area. Norway lemmings are hunted by both of these foxes, and Arctic foxes specialize in hunting lemmings specifically. It has been suggested that having more information on Norway lemming populations could help understand how to support threatened Arctic fox populations. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Arctic Fox Reproduction and Lemming Boom-and-Bust Cycle

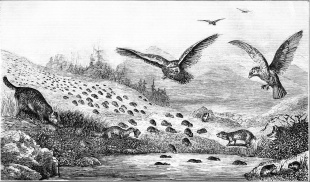

The numbers of both mammalian and avian predators depend on the lemming fluctuations. In low lemming years, resident mammalian predators, including the Arctic fox, ermine, and least weasel, hardly breed. During peak years, Arctic foxes can have litters of up to 20 kits, and ermine and weasel numbers increase rapidly. Many species of birds of prey move nomadically, or briefly visit their breeding grounds in the Arctic in the search of lemming peaks. Snowy owls and jaegers (or skuas) are particularly well-known for their dependence on lemmings, breeding only in years when lemmings are abundant. [Source: barentsinfo.org]

The population densities of Fennoscandia predators have been shown to be tied to the population cycles of lemmings and other small rodents with cyclic population changes. Alexandria Stubblefield wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Fall is a particularly opportune time for lemming predators because there is no snow cover and plant food sources are scarce due to freezing temperatures. With less available food, lemmings may stray further away from their burrows than usual and leave themselves vulnerable to predation. Their burrows, whether in the ground or under the snow, are a lemming's main defense against predators. Aerial predators and larger predators have a more difficult time accessing the burrows. Predators such as ermines and weasels may be able to find their way into the lemmings' burrows. [Source: Alexandria Stubblefield, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lemming numbers have a huge impact on litter size. of Arctic foxes. John L. Eliot wrote in National Geographic, “ In 2002, when lemmings crashed in much of Canada, photographer Rosing found two sleepy pups in a den of only seven on Victoria Island in the Canadian Arctic. The following year, when lemmings were plentiful, "this den near Churchill had 13 pups", says Rosing, "and it was littered with lemming and bird carcasses." One of the den's adults for ages to feed its young.[Source: John L. Eliot, National Geographic, October 2004]

In good lemming years one female may have up to 20 pups, and local arctic fox populations boom. When lemming numbers plummet, many arctic foxes starve in winter, leading to fewer and smaller litters. Critical to foxes during lean lemming years, about 100,000 snow geese nest on La Pérouse Bay near Churchill. "I found 72 geese feet in one Churchill den," says ecologist James Roth In years when food is abundant, adults feed their young through the summer until autumn, when the pups disperse. In lean years the pups leave the den earlier, to hunt on their own in a land where success is never a sure thing.

Do Lemmings Explode?

According to Encyclopedia Britannica: Some people thought that lemmings explode if they become sufficiently angry. This is a myth, of course — lemmings are indeed one of the more irascible rodents, but they mostly channel their rage into fights with other lemmings. People probably came up with the notion of exploding lemmings after seeing the picked-over lemming carcasses that were left behind following a migration.

At the peak of their reproductive cycle, lemmings become noticeably more aggressive. "A person walking across the meadow would cause the lemmings, several meters away, to give themselves away by unexpectedly shrieking and jumping about," noted one group of researchers. "Even the farm tractor was greeted in this way, leaving a trail of infuriated lemmings behind." [Source:Henry Nicholls, BBC, November 21, 2014]

Henry Nicholls of the BBC wrote: In the months after a reproductive boom, lemming predators will have a field day, slaying but not eating their victims. Once ravens have pecked their way through these killing fields, the eviscerated lemmings do look like they might have burst with anger. What's more, Nils Christian Stenseth of the University of Olso in Norway, and co-author of The Biology of Lemming, points out, "no one has seen a lemming explode."

Mystery of Lemming Mass Migrations

Lemmings have large population booms every three or four years. When the concentration of lemmings becomes too high in one area, a large group sets out in search of a new home. Seventeenth century naturalists were bewildered by the habit of Norway lemmings to suddenly appear in large numbers, seemingly out of nowhere, and concluded that the animals were being spontaneously generated in the sky and fell to earth like rain. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

In 1823, one explorer wrote of seeing "such inconceivable numbers" in his Scandinavian travels "that the country is literally covered with them". An army of lemmings advanced with extraordinary purpose, "never suffering itself to be diverted from its course by any opposing obstacles," not even when confronted by rivers, or even the branches of narrow fjords.

David Attenborough wrote: “Every thirty or forty years or so in the autumn there is a population explosion on an altogether different scale. It’s causes are still not properly understood. Suddenly from the upland forests of Scandinavia, a great tide of lemmings emerges and starts to flow down towards the valleys, advancing by a s much as ten miles a day. The animals invade cultivated fields, destroying the crops. They swarm into gardens and houses, They tumble down wells where their rotting bodies foul the water. In 1970, on a 120-mile stretch of road, 20,000 were killed by cars. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

“The lemmings as they search frantically for food, become very aggressive. Indeed, they are so ferocious that they will attack creatures many time their size — including human beings. Fights may break out between them as they rush wildly onwards, searching for new territory and more food. If they reach a river, the pressure of those advancing behind them may force the leaders to take to the water. They are very competent swimmers. Their dense buoyant fur causes them to ride high in the air with their backs fully exposed, so the surface of the water appear to be clotted with them. The animals are able to avoid swimming in circles for they can orientate themselves

Lemming Mass Suicides?

It has been suggested that lemmings die off in mass suicides by jumping off seaside cliffs. Instinct, it has been said, drives them to kill themselves whenever their population becomes unsustainably large. According to one take on this view massive groups of lemmings march in a straight line to some unknown destination, devouring everything in their path. If the lemmings come to a lake, they try to swim across it, with many drowning in the process. If they encounter a boat they climb over it and continue in their straight line. "If they come across a man they glide between the legs," one scientist wrote. "if they meet with a haystack they gnaw through it. If a rock stands in their way they go around it in a semicircle and then resume the straight line of their match."

Any attempt to disrupt their march is met with great resistant—fighting and barking. Finally when the multitude reaches the sea, they continue right on marching to their deaths, or fall en mass from cliffs. A few stay behind and return to their home range to breed. There are so few of them at this point that they are rarely seen until their population begins growing once again and the cycle continues.

Why is the myth of mass lemming suicide so widely believed? According to Encyclopedia Britannica; For one, it provides an irresistible metaphor for human behavior. Someone who blindly follows a crowd — maybe even toward catastrophe — is called a lemming. Over the past century, the myth has been invoked to express modern anxieties about how individuality could be submerged and destroyed by mass phenomena, such as political movements or consumer culture.

Disney and the Lemming Mass Suicides Myth

Disney has played a big role in the perpetuation of lemming suicide myth. For the 1958 Disney nature film “White Wilderness”, according to Encyclopedia Britannica filmmakers eager for dramatic footage staged a lemming death plunge, pushing dozens of lemmings off a cliff while cameras were rolling. The images — shocking at the time for what they seemed to show about the cruelty of nature and shocking now for what they actually show about the cruelty of humans — convinced several generations of moviegoers that these little rodents do, in fact, possess a bizarre instinct to destroy themselves. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

“White Wilderness”, made by filmmaker James Alga, won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. It wasn’t until 1983, when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's investigative journalism program The Fifth Estate did an expose called “Cruel Camera “, was it revealed that the lemming scenes in the film were staged.

Andrew Tarantola wrote in gizmondo.com: The Disney film :White Wilderness” was made in Alberta, Canada. Lemmings aren't native to that region so the production crew imported a few dozen of the animals for the shoot. Also, the species of lemming that they lined up do not migrate. Some species of lemmings do migrate but you'll never see a herd of migrating lemmings like you do in the film As such, the crew actually had to employ a snow-covered turntable to make it appear that they were "migrating" when they were really just running in circles. After the crew had a sufficient number of these migratory shots, the animals were herded over to the bank of a nearby river and unceremoniously chucked into the water, where they drowned.

Henry Nicholls of the BBC wrote: Stenseth is generous about the movie. "It is a nice film actually," he says. "But there are some bits and pieces that are wrong with it. The accounts of mass movements were all based on observations of Norway lemmings, not the West Siberian lemmings that Disney used. They paid Eskimos "$1 a live lemming," says Stenseth. [Source: Henry Nicholls, BBC, November 21, 2014]

They didn't march to the sea. They were tipped into it from the truck In an infamous sequence, the lemmings reach the edge of a precipitous cliff, and the voiceover tells us that "this is the last chance to turn back, yet over they go, casting themselves bodily out into space." It certainly looks like suicide. "Only they didn't march to the sea," says Stenseth. "They were tipped into it from the truck." Once you know the sequence has been faked, it makes for rather awkward viewing. Several of the West Siberian lemmings pause at the edge. One or two look like they are trying to turn back. They don't want to be there at all. They don't want to jump. It looks less like suicide and more like murder.

Explanation for Lemming Population Booms and Mass Die-Offs

Henry Nicholls of the BBC wrote: Based on data collected between 1970 and 1997, Stenseth and his colleagues were able to demonstrate in 2008 that what lemmings really need to thrive is the right kind of snow. "If the snow is soft and dry then a space under the snow builds up within which the lemmings can survive very well during the winter and reproduce very well," says Stenseth. If there are a couple of consecutive winters like this, vast numbers of lemmings can emerge in the spring, as if from nowhere. That's when the trouble starts. With too many hungry lemmings about, the vegetation quickly gets overgrazed and the animals are forced to seek pastures new. It is in these circumstances, as they move from higher to lower ground, that they can occasionally tumble down a slope. "By way of gravitation they tend to move downwards," says Stenseth. [Source: Henry Nicholls, BBC,November 21, 2014]

A study released in 2003 on lemmings in Greenland indicated that the primary reason that lemming populations crash so suddenly and dramatically is because of predators not mass suicides. Observations of collared lemmings over a 1 year period showed that the decimation of lemming populations was the result of four primary predators: snowy owls, long-tailed skuas (a kind of seabird), arctic foxes and stoats (short-tailed weasels or ermines).

The study found that tundra where the lemmings lived provided abundant food sources and soft soil for them to burrow in. Their high reproduction rates meant that they could quickly produce large numbers of themselves. When their numbers rose to a certain level the animals mentioned above began eating more and more and more of them. One pair of snowy owls brought up to 50 lemmings a day aback to their nest to feed their chicks. Stoats also can reproduce frequently so that when lemming offered a plentiful food source they began reproducing more quickly and ate more lemmings.

Another theory for the lemming boom and bust cycle that has been given some serious consideration is the lemming’s eating habits. The animals mostly eat sedges and grasses which produce a chemical that neutralizes the lemmings digestive juices. If the lemming eat moderately, which they do in most situations, the plants stop producing the chemical after 30 hours. When the animals eat intensely, which they do when the population explodes, the plants keep producing the chemical, which causes the lemmings to eat continuously but still be hungry, According to the theory, they swim into lakes and drown themselves as they search of food after the land has been stripped.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025