WOLVES

Wolves are the largest of the wild canids, which include jackals and coyotes. They are ancestors of dogs and rank with bears and large cats such as cougars and snow leopards as the largest predators in their ranges. They are the only animal that can routinely bring down large mammals several times their size such as moose and elk. [Source: Douglas Chadwick, National Geographic, May 1998, William Stevens, New York Times, January 31, 1995; David Nevin, Smithsonian magazine]

Jane Goodall wrote in the Washington Post: Wolves are highly intelligent, have a rich emotional life and are an intensely social species. They remain with their parents for at least three years, learning how to be good pack members, and they are likely to grieve over the death or disappearance of a companion. Wolves travel long distances in search of prey. each pack is composed of bonded individuals. When leaders are killed, the pack and its traditions may disintegrate. When breeders are killed, the pack’s survival is threatened even more directly. [Source: Jane Goodall, Washington Post, January 5, 2014]

For the most part what we call wolves are gray wolves (Canis lupus), which can also be spelled grey wolves. Wolves live above 15 degrees north latitude around the globe. They are found in Europe, Asia and North America, ranging from the Arctic to as far south as Mexico, India and Turkey. For thousands of years they were the most widespread carnivores after human beings. There are currently about 400,000 wolves in the world, compared to 400 million dogs.

Book: “Never Cry Wolf” by Farley Mowatt. “The Wolf” by David Mech a research biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and regarded as the world's most knowledgeable person about wolves

RELATED ARTICLES:

CANIDS, CANINES AND CANIS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

DOG AND WOLF HISTORY: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, HYBRIDS AND RECORDS europe.factsanddetails.com

WOLF BEHAVIOR: PACKS, HIERARCHIES, MATING, PUPS factsanddetails.com;

GRAY WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WOLF FOOD: DIET, HUNTING: PREY, TACTICS, FEEDING HABITS factsanddetails.com;

WOLVES AND HUMANS: STORIES, LIVESTOCK, REWILDING factsanddetails.com

WOLF ATTACKS ON HUMANS: WHERE, WHY, WHEN, HOW factsanddetails.com

WOLF ATTACKS ON HUMANS IN ASIA AND THE FORMER USSR factsanddetails.com

WOLF ATTACKS ON HUMANS IN INDIA factsanddetails.com

DOGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND INTELLIGENCE europe.factsanddetails.com

DOMESTICATION OF DOGS: THEORIES, EVIDENCE, WHY AND HOW europe.factsanddetails.com

WHEN AND WHERE DOGS WERE FIRST DOMESTICATED europe.factsanddetails.com

Wolf Evolution and History

Dogs and canids (wolf-like and dog-like animals) evolved from hesperocyons, predators that looked somewhat like jackals and lived 37 million years ago in North America. They had distinctive pairs of shearing teeth and ran down prey. Some regard the first canid as Prohesperocyon wilsoni , a creature that lived in what is now southwestern Texas about 40 million years and had teeth that were evolved towards a more shearing bite. It ancestors had more elongated limbs and toes packed close together which facilitated running faster. As their prey began runner faster they too adapted by running faster themselves They also developed the ability to crack and eat bones, which suggests that regularly scavenged carcasses. Early canids reached Europe about 7 million years ago. The Eucyon, a species that arose 7 million years and moved west 6 million to 4 million years ago, gave birth to most modern canids, including wolves, coyotes, jackals and dogs.

The ancestors of the first wolves are believed to have evolved in North America and crossed the Bering Strait during one of the Ice Ages (Glacial Maximum periods) and dispersed in Asia, then Europe and finally the Middle East and Africa. Modern gray wolves (C. lupus) are widely recognized as descending from the earlier C. mosbachensis (which lived around around 1.4 million to 400,000 years) and they in turn descended from Etruscan wolves (C. etruscus) (which lived around around 1.81 million to 781,000 years ago). The oldest fossils of the modern gray wolves include ones from Ponte Galeria in Italy, dating to 406,500 years ago. Remains from Cripple Creek Sump in Alaska may be considerably older, at around 1 million years old, but are not totally accepted as modern wolf fossils as differentiating between the remains of modern wolves and C. mosbachensis is difficult and ambiguous. [Source: Wikipedia]

Considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves by the Late Pleistocene Period (129,000 to 11,700 years ago). At that time wolf populations had more robust skulls and teeth than modern wolves, often with a shortened snout, a pronounced development of the temporalis muscle (used for jaw movements), and robust premolars. It has been hypothesized that these features were specialized adaptations for the processing of carcass and bone associated with the hunting and scavenging of large Pleistocene animals. Compared with modern wolves, some Pleistocene wolves had more broken teeth. This suggests they either often processed carcasses and cracked open bones like modern hyenas or they competed with other carnivores and needed to consume their prey quickly.

Genomic studies suggest modern wolves and dogs descend from a common ancestral wolf population. A 2021 study found that the Himalayan wolf and the Indian plains wolf are part of a lineage that split off from other wolves about 200,000 years ago. Other wolves appear to share most of their common ancestry within the last 23,000 years (around the time of the peak and the end of the Last Glacial Maximum) and originated from Siberia or Beringia. Some scientists have suggested that this was a result of a population bottleneck, but studies have also suggested it was a consequence of gene flow homogenising ancestry.

A 2016 genomic study suggests that Old World and New World wolves split around 12,500 years ago followed by the divergence of the lineage that led to dogs from other Old World wolves around 11,100–12,300 years ago. An extinct Late Pleistocene wolf may have been the ancestor of the dog, with the dog's similarity to the extant wolf being the result of genetic admixture between the two. The dingo, Basenji, Tibetan Mastiff and Chinese indigenous breeds are basal members of the domestic dog clade. The divergence time for wolves in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia is estimated to be fairly recent at around 1,600 years ago. Among New World wolves, the Mexican wolf diverged around 5,400 years ago.

See Separate Article: DOG AND WOLF HISTORY: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, HYBRIDS AND RECORDS europe.factsanddetails.com

32,000- and 44,000 Year-Old Wolves Found in Russian Permafrost

In June 2019, scientists announced the discovery of an intact head of a gigantic adult wolf which died about 32,000 years ago and was preserved in permafrost in the Russian Arctic. Found by a local on the banks of the Tirekhtyakh River in Russia's remote Arctic region of Yakutia in the summer of 2018, the head is covered with thick fur and features a well-preserved brain, soft tissue and a set of powerful teeth and measures 41.5 centimeters (16 inches) in length. By comparison, the kull of a modern gray wolves is 23 to 28-centimeters (9.1 to 11-inches) long and their torso is between 66 and 86 centimeters (26 to 34 inches) long. The head was taken to Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo to study. "It is the first ever such find," Albert Protopopov, head of mammoth fauna studies at the Yakutia Academy of Sciences, told AFP. "Only cubs have been discovered before." The wolf is believed to have been between two and four years old when it died and dates to a period in the Pleistocene epoch when megafauna such as woolly mammoths roamed the Earth. “Protopopov said the scientists from Russia, Japan and Sweden would continue to study the head. "We are hoping to understand whether this was a separate subspecies," he added. Several species of ancient wolf lived during the Ice Age including now-extinct dire wolf that featured in the popular TV series Game of Thrones, which lived in the Americas. [Source: AFP, June 15, 2019]

In 2021, a complete, 44,000-year-old mummified wolf was discovered in the Siberian permafrost by a river in the Republic of Sakha — also known as Yakutia. It was the first complete adult wolf dating to the late Pleistocene period ever discovered, according to a statement from the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, where a necropsy (animal autopsy) on it was performed. According to Live Science: Photos from the necropsy show the wolf's mummified body in exquisite detail. Animals are preserved in permafrost through a type of mummification involving cold and dry conditions. Soft tissues are dehydrated, allowing them to be preserved. Researchers took samples of the wolf's internal organs and gastrointestinal tract to detect to understand its diet when it died. "His stomach has been preserved in an isolated form, there are no contaminants, so the task is not trivial," Albert Protopopov, head of the department for the study of mammoth fauna of the Academy of Sciences of Yakutia, said in the statement. "We hope to obtain a snapshot of the biota of the ancient Pleistocene." [Source: Hannah Osborne, Live Science, June 26, 2024]

Tooth analysis revealed the wolf was a male and was an "active and large predator." The scientists should be able to find out what it was eating, along with the diet of its victims, which "also ended up in his stomach." Another key aspect of the necropsy is looking at the ancient viruses the wolf may have harbored. "We see that in the finds of fossil animals, living bacteria can survive for thousands of years, which are a kind of witnesses of those ancient times," Artemy Goncharov, who studies ancient viruses at the North-Western State Medical University in Russia, and is part of the team analyzing the wolf, said in the statement.

He said the research project will aid their understanding of ancient microbial communities and the role of harmful bacteria during this period. "It is possible that microorganisms will be discovered that can be used in medicine and biotechnology as promising producers of biologically active substances," he added. The wolf necropsy is part of an ongoing project to study the wildlife that lived in the region during the Pleistocene. Other species examined include ancient hares, horses and a bear from the Holocene. The team plans to study the wolf's genome to understand how it relates to other ancient wolves from the region, and how it compares to its living relatives. The team now plans to start studying another ancient wolf discovered in the Nizhnekolymsk region of northeast Siberia in 2023.

Wolf Species

There are three widely recognized species of wolves: 1) gray wolves (Canis lupus), 2) red wolves (Canis rufus), and Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis). Some researchers also consider eastern wolves (Canis lycaon) to be a distinct species, while others classify it as a subspecies of the gray wolf, according to the International Wolf Center. [Source: Google AI, Wikipedia]

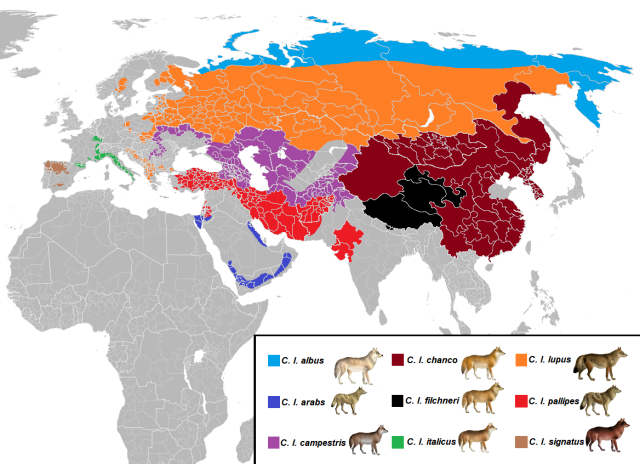

Gray Wolves (Canis lupus): are the most common and widely distributed wolf species. They found in North America, Europe, Asia and parts of Africa. Many wolves with their own names such as Arabian wolves, Arctic wolves and Indian wolves are subspecies of gray wolves.

Red Wolves (Canis rufus) are a relatively smaller wolf species primarily found in North America. They are facing significant conservation challenges and are labeled as critically endangered. There are thought to be 15 to 25 adults in the wild remaining from the reintroduction efforts in the late 1980s mostly in eastern North Carolina. Major issues concerning the Red wolf are hybridization with coyotes that also live within the area and habitat destruction, and human conflict issues within the South Eastern United States. |=|

Ethiopian Wolves (Canis simensis) are also known as Abyssinian wolves. They are a unique species found in the Ethiopian Highlands and labeled as endangered, with only a couple hundred left. The majority of Ethiopian wolves live within the Bale Mountains in Ethiopia. They sometimes live in relatively high population densities which means it is easier for diseases such as Canine Distemper Virus to spread and impact the entire population. According to ScienceAlert: With fewer than 500 individuals in the wild, the Ethiopian wolf is Africa's most endangered carnivore. Like many of Earth's most endangered species, this unique wolf is a specialized feeder, dining mostly on specific rodents found in the mountainous regions of Africa, and nectar from specific flowers. Just like its primary prey, the wolf is also only found over seven mountain ranges, isolated above altitudes of 3,000 meters. Genetics suggests these wolves are a remnant ancestral group of a line of canids that eventually became Gray wolves. [Source: Tessa Koumoundouros, ScienceAlert, December 1, 2024]

Maned Wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) are large canines that live South America in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay, and is almost extinct in Uruguay. They have long legs, almost like those of hyenas, and their markings resemble those of foxes, but it they neither foxes nor moves. They are the only species in the genus Chrysocyon (meaning "golden dog" in Ancient Greek)

Wolf Characteristics

Wolves generally weigh between 35 and 55 kilograms (80 and 120 pounds), with males typically weighing between 43 and 45 kilograms (95 and 100 pounds) and females between 35 and 37 kilograms (80 and 85 pounds). The largest wolf on record weighed 78 kilograms (172 pounds).

Wolves may stand one meter at the shoulder and live an average of five years or so in the wild if they reach maturity at age two or three. Under ideal conditions they can reach 15 years of age. Wolves come in a variety of colors including pure white, jet black, cream, grey, buff, tawny, reddish and even bluish. Those that live full time in the Arctic are often white.

Wolves have fur up several centimeters (inches) thick to keep them warm in winter and jaws powerful enough to crack open bones to extract the marrow. The have huge paws, that can make a print 10 centimeters (four inches) across in the snow. There long and thin legs make them look somewhat awkward when standing still but these legs are ideal for bounding through grasslands, brush and forest and through snow in the winter.

Wolves often die of hunger, especially when they are young. They are also affected by distemper, parovirus, heartworm, and intestinal parasites. As they get older their teeth wear down. Old wolves often have to rely on other member of the pack to tear off hunks of meat for them.

Black Wolves Got Their Color from Domestic Dogs

Black wolves — gray wolves found almost exclusively in North America — likely inherited their coats from breeding with domestic dogs, according to a study published in February 2009 in the journal Science. Dogs dogs of the earliest Native Americans or of European immigrants probably contributed to the genetic variability of their wild counterparts, researchers from Stanford University and the University of Calgary found, [Source: AFP, February 6, 2009]

Most canine geneticists believe that North American dogs today are all descended from European dogs, the study said. "Although it happened by accident, black wolves are the first example of wolves being genetically-engineered by people," said study co-author Marco Musiani, a University of Calgary professor and wolf expert. "Domestication of dogs has led to dark-colored coats in wolves, which has proven to be a valuable trait for wolf populations as their arctic habitat shrinks," Musiani said.

AFP reported: A darker coat helps wolves hide when chasing their prey in forested areas, where the black wolves make up about 62 percent of the wolf population. Wolves gray with age, and coats vary from white to gray to black. Lighter-colored wolves are more prevalent in the icy tundra, where only about seven percent of dark wolves are found. "I have spent a lot of time in tree-line areas at the southern edge of the tundra and it has always surprised me that there are white wolves and black wolves but no gray wolves in these areas," Musiani said. "This work may provide an explanation: Wolf populations are quickly adapting to conditions with less snow by taking advantage of the human-created shortcut of black coloration."

The researchers said the wolves acquired their dark coats at some point over the past 10 000 to 15 000 years, after the first humans migrated to North America across the Bering Strait with their dogs. The study compared DNA from 41 black, gray and white wolves in the Canadian Arctic and 224 black and gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park with the DNA of domestic dogs and gray and black coyotes.

The researchers set out to explain how pigmentation in dogs differs from most other mammals, but instead discovered the genetic mutation that accounts for wolves' pigmentation. "Wildlife biologists don't really think that wolves rely much on camouflage to protect themselves or to increase their hunting success," said genetics professor Greg Barsh. His laboratory discovered in 2007 that the gene responsible for black fur in dogs belongs to a family of genes believed to help fight infection. "It's possible there is something else going on here. For example, the protein responsible for the coat color difference has been implicated, in humans, in inflammation and infection, and therefore might give black animals an advantage that is distinct from its effect on pigmentation," Barsh said.

How Many Wolves Are There in the World Today?

It's estimated that there are around 200,000 to 250,000 wolves remaining in the world today, with the vast majority of them being grey wolves. Russia was estimated,to have about 67,000 wolves as of 2021. Canada has over 60,000 wolves, with 5,000 in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut 5,000 in the and Yukon, 8,500 in British Columbia, in Alberta 7,000, 4,300 in Saskatchewan, 4,000-6,000 in Manitoba, 9,000 in Ontario, 7,000 in Quebec and 2,000 in Labrador.

As of 2017, the United States was home to 18,000 wolves, with about two thirds of them in Alaska. Wolves in the continental U.S. in the early 2010s: A) Gray Wolves: 27 in Washington; 59 in Oregon; 1 in California; 653 in Montana; 328 in Wyoming; 746 in Idaho; 2,921 in Minnesota; 782 in Wisconsin; 703 in Michigan; B) Mexican gray wolves: 58 in Arizona; 26 in New Mexico; Red Wolves: 100 in North Carolina

Kazakhstan had a stable population of about 30,000 wolves in the 2000s. Lider et al. (2020) estimated the population of wolves in the country in 2018 as 13,200 animals. Before that it had been said there 150,000 wolves in Kazakhstan. Mongolia has a stable population of 10,000–20,000 wolves. [Source: Wikipedia

A large percentage percent of the world’s wolves live in the circumpolar countries, although the number actually living in the Arctic is unknown. Wolf management practices reflect a long history of exploitation and predator control by humans. The high reproductive potential and dispersal behavior of wolves, however, contribute to their persistence in many areas and to their repopulation of historical range in others. [Source: barentsinfo.org]

In, Russia wolves are found across about three-quarters of the country. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, wolf research and monitoring declined. Russia has no legal protection for wolves except in nature reserves. Hunting can occur throughout the year. An estimated 15,000 wolves are killed annually. Although wolf populations in most areas are thought to be stable or increasing, recent estimates in northwestern Russia (Kola and Karelia regions) show declines in the late 1990s.

While wolves are abundant in Alaska, northern Canada, and Russia, local overharvests may occur. Habitat loss continues to be a concern for wolf conservation, especially in areas with recovering wolf populations. Wolves are also regarded by many as a nuisance species, hampering management and recovery plans. The challenge continues to be the development and public acceptance of a flexible conservation plan that accommodates wolves in wilderness, but allows for local conflict management.

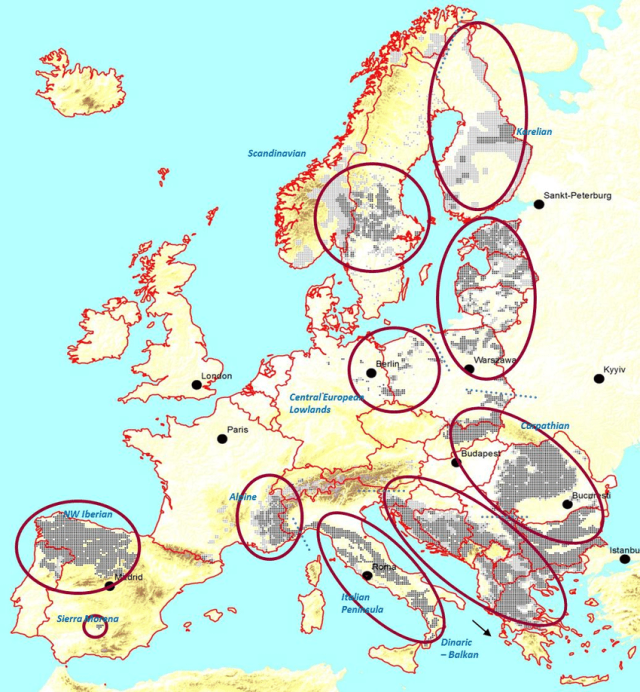

The total wolf population in Finland is estimated to be 100 animals, about 30 of which are shared with Russia. They are protected south of the reindeer areas, and subject to a five-month harvest season within the reindeer herding areas. The total kill ranges from 5-15 wolves per year. In winter 2000-2001, 29 animals were killed, which was about 25 percent of the total population. Sweden currently has about 50-70 wolves. Wolves have been protected throughout the country since 1966, but negative attitudes still persist. Norway has approximately 22-24 wolves. Wolves have been protected in Norway since 1973, although conflicts with livestock led to culling of nine wolves in early 2001. The wolf populations in the northern parts of all three countries are unstable, and consist mostly of animals wandering from other regions. Conflicts with reindeer herding complicate the protection of wolves in the CAFF region of Fennoscandia. A recently proposed policy would facilitate the dispersal of wolves from Finland and Russia to both Norway and Sweden.

Never Cry Wolf

“Never Cry Wolf” by Farley Mowat is an account of the author’s experience observing wolves in subarctic Canada. It was first published in 1963 and was adapted into a film of the same name in 1983. It has been credited for dramatically changing the public image of the wolf to a more positive one. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the book, Mowat describes his experiences in a first-person narrative that sheds light on his research into the nature of the Arctic wolf. In 1948–1949, the Dominion Wildlife Service assigns the author to investigate the cause of declining caribou populations and determine whether wolves are to blame for the shortage. Upon finding his quarry near Nueltin Lake, Mowat discovers that rather than being wanton killers of caribou, the wolves subsisted quite heavily on small mammals such as rodents and hares, "even choosing them over caribou when available."

He concluded: "We have doomed the wolf not for what it is but for what we deliberately and mistakenly perceive it to be: the mythologized epitome of a savage, ruthless killer — which is, in reality, not more than the reflected image of ourselves. We have made it the scapewolf for our own sins." Mowat writes to expose the onslaught of wolfers and government exterminators who are out to erase the wolves from the Arctic.

Mowat's book says that: The main reason for declining population of caribou is human hunters from civilization. Wolves that hunt a large herd animal would rather attack weaker, injured, or older animals, which helps rid the herd of members that slow its migration. Arctic wolves usually prey on Arctic ox, caribou, smaller mammals, and rodents — but since they rely on stamina instead of speed, it would be logical for the wolves to choose smaller prey instead of large animals like caribou, which are faster and stronger, and therefore a more formidable target. One of these animals may include mice.A lone Arctic wolf has a better chance of killing small prey by running alongside it and attacking its neck. The wolf would be at a disadvantage if it attacked large prey from behind, because the animal's powerful hind legs could injure the wolf. However, a group of wolves may successfully attack large prey from a number of positions. Since Arctic wolves often travel in a group, their best strategy is not to kill surplus prey, since the whole group can sate themselves on one or two large animals. There are, however, exceptions to this. There are many local Eskimos, the majority of whom are traders. The Eskimos can interpret wolves' howls. They can tell things such as whether a herd or a human is passing through the wolves' territory, the direction of travel, and more.

Barry Lopez in his 1978 work Of Wolves and Men called the book a dated, but still good introduction to wolf behaviour. In "Never Cry Wolf: Science, Sentiment, and the Literary Rehabilitation of Gray wolves", Karen Jones wrote in The Canadian Historical Review vol.84 (2001)lauded the work as "an important chapter in the history of Canadian environmentalism": The deluge of letters received by the Canadian Wildlife Service from concerned citizens opposing the killing of wolves testifies to the growing significance of literature as a protest medium. Modern Canadians roused to defend a species that their predecessors sought to eradicate. By the 1960s the wolf had made the transition from the beast of waste and desolation (in the words of Theodore Roosevelt) to a conservationist cause celebre....Never Cry Wolf played a key role in fostering that change.”

At the time it was published, Mowat's book received criticism, often politically-motivated, about the veracity of his work and its conclusions. Canadian Wildlife Service official Alexander William Francis Banfield, who supervised Mowat's field work, characterised the book as "semi-fictional", and accused Mowat of blatantly lying about his expedition. He pointed out that contrary to what is written in the book, Mowat was part of an expedition of three biologists, and was never alone. Banfield also pointed out that a lot of what was written in Never Cry Wolf was not derived from Mowat's first hand observations, but were plagiarised from Banfield's own works, as well as from Adolph Murie's The Wolves of Mount McKinley.. In a 1964 article published in the Canadian Field-Naturalist, he compared “Never Cry Wolf” to Little Red Riding Hood, claiming that, "I hope that readers of Never Cry Wolf will realize that both stories have about the same factual content."

In 2012, Mowat spoke to the Toronto Star about his self-acknowledged reputation as a storyteller: “For years I felt the Toronto media were out to bury me alive," referring to latter-day efforts in the literary community to reassess his work according to the standards of modern journalism as opposed to memoir. “That was never my game,” he said. “I took some pride in having it known that I never let facts get in the way of a good story. I was writing subjective non-fiction all along.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025