BUNRAKU

male puppet “Bunraku” is Japan’s professional puppet theater. Performed with chanting, a three-stringed shamisen and puppets, each of which is usually manipulated by three people, and also known as “joruri” (narrative chanting), it developed at the end of the of the 16th century, about the same time that the samisen was introduced from Okinawa and kabuki performances started in the Kyoto area. In 2003, bunraku was designated by UNESCO as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Bunraku is deeply associated with Osaka. [Source: Paul Jackson, Yomiuri Shimbun]

Bunraku is named after a promoter named Uemura Bunrakuken who popularized the form in the 19th century. Bunraka did not originate in Osaka but it was popularized there. Bunraku is performed only by men, and is performed mostly at national theaters in Osaka and Tokyo. Bunraku was once very popular and loved by ordinary people but these days its audience is in decline and many associate it with high-brow culture. Marionette versions of Noh and kabuki were once popular but these art forms have largely died out and are performed manly with knee-high puppets at the Yuki-za Marionetter Theater in Tokyo.

Developed primarily in the 17th and 18th centuries, “bunraku” is one of the four forms of Japanese classical theater, the others being “kabuki”, noh”, and “kyogen”. The term bunraku”comes from Bunrakuza, the name of the only commercial “bunraku”theater to survive into the modern era. Bunraku”is also called “ningyo joruri”, a name that points to its origins and essence. Ningyo”means “doll” or “puppet,” and “joruri”is the name of a style of dramatic narrative chanting accompanied by the threestringed shamisen”. Together with “kabuki”, “bunraku”developed as part of the vibrant merchant culture of the Edo period (1603-1868). Despite the use of puppets, it is not a children’s theater. Many of its most famous plays were written by Japan’s greatest dramatist, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), and the great skill of the operators make the puppet characters and their stories come alive on stage. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Bunraku, a form of puppet theater, created during the early Edo period (1603–1868), is without doubt the most spectacular tradition of puppetry in the whole world. Its puppets, approximately one meter high, are manipulated by black-robed puppeteers on a wide stage, while narrators chant the story in a highly expressive manner to the accompaniment of shamisen music. Either the stories are taken from the story collections depicting the bloody wars of Japan’s feudal period or they focus on the fates of townspeople in the Edo period. The plays include heartbreaking tragedies and represent Japanese dramatic literature of the highest order. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Good Websites and Sources: Bunraku Official Site bunraku.or.jp ; Japan Arts Council www2.ntj.jac.go.jp ; Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Bunraku in the Bay Area bunraku.org ; Books: “The Bunraku Handbook” by Hironaga Shuzaburo (Maison ds Arts, 1976). A variety of guides and booklets are also available from the Japanese National Tourist Office (JNTO) and Tourist Information Centers (TIC).

Bunraku Puppet Theater can be seen in Osaka at the National Bunraku Theater of Japan in Minami Ward. Tickets are generally around $35 to $50. English interpretations are available through earphones. Gion Corner at Yasaka Kaikan Hall in Kyoto features a one-hour show with quick demonstrations of seven different traditional art forms: the tea ceremony, flower arranging, koto music, “gagaku” (ancient court music), “kyogen” (traditionally comic drama), bunraku puppet drama and geisha-style women dances. Shows in English are conducted twice daily at 8:00pm and 9:10pm March through November. Website: Gion Corner kyoto-gion-corner.info

Links in this Website: NOH THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KABUKI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUNRAKU, JAPANESE PUPPET THEATER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KYOGEN, RAKUGO AND THEATER IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GEISHAS AND THE MODERN WORLD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FOLK MUSIC AND ENKA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DANCE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

History of Bunraku

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Puppetry has a long history in Japan. It is believed that it has its roots in ancient rites in which puppets served as representatives of deceased persons. When contacts with China were established in the 7th century, puppetry was also adopted from there, among other cultural elements. Written evidence exists from the Heian period 794–1185 that mentions travelling groups of puppeteers. They used simple, one-man-operated puppets. Another form of art, similarly practised by travelling artists, was storytelling. The storytellers narrated tales about famous battles of the feudal period.Bunraku, or hingyo joruri, as it was originally called, evolved when puppeteers and storytellers began co-operating by the end of the 16th century. A third group of artists, who participated in this creation of a new art form, were shamisen players. Shamisen, a plucked instrument, which was adopted from China, became the most fashionable instrument of the Edo period. ** [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

In the Heian period (794-1185), itinerant puppeteers known as “kugutsumawashi”traveled around Japan playing door-to-door for donations. In this form of street entertainment, which continued up through the Edo period, the puppeteer manipulated two hand puppets on a stage that consisted of a box suspended from his neck. A number of the “kugutsumawashi”are thought to have settled at Nishinomiya and on the island of Awaji, both near present-day Kobe. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In the 16th century, puppeteers from these groups were called to Kyoto to perform for the imperial family and military leaders. It was around this time that puppetry was combined with the art of “joruri”. A precursor of “joruri”can be found in the blind itinerant performers, called “biwa hoshi”, who chanted “The Tale of the Heike”, a military epic depicting the Taira-Minamoto War, while accompanying themselves on the “biwa”, a kind of lute. In the 16th century, the “shamisen”replaced the “biwa”as the instrument of choice, and the “joruri”style developed. The name “joruri”came from one of the earliest and most popular works chanted in this style, the legend of a romance between warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune and the beautiful Lady Joruri.

Bunraku, the result of the fusion of three art forms—puppetry, music and storytelling — reached its artistic peak in the early 17th century. During the early 18th century the originally rather small puppets grew to their present dimensions. Their mechanism became so delicate and complex that three puppeteers were required to manipulate one puppet. It was of the utmost importance for bunraku’s popularity that leading dramatists wrote plays for its repertoire. Among them was Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724), who originally wrote plays for the sensational kabuki theater. It developed side by side with bunraku. He became fed up, however, with kabuki’s commercial and erotic populism and started to write plays for bunraku. **

“The art of puppetry combined with chanting and “shamisen”accompaniment grew in popularity in the early 17th century in Edo (now Tokyo), where it received the patronage of the “shogun”and other military leaders. Many of the plays at this time presented the adventures of Kimpira, a legendary hero renowned for his bold, outlandish exploits.

The decline in bunraku’s popularity began during the early Meiji period (1868–1912), when Westernised forms of entertainment became fashionable. Kabuki, however, was able to maintain its popularity and it included in its repertoire many plays originally written for bunraku. The continuation of the tradition was, however, ensured by a prolific bunraku artist, Masai Kahei (1737–1810), with the stage name of Ueamura Bunrakuken. He founded his own puppet theater in Osaka in 1871, and he gave the art form, originally called ningyo joruri, its present name, bunraku. Thus Osaka became the home of bunraku. There the tradition was continued during the Meiji period and further on until our times. Osaka’s Bunraku-za or Bunraku Theater is still the centre of the art form, although performances can also be seen at the National Theater of Tokyo. **

Chikamatsu Era in Bunraku

It was in the merchant city of Osaka, however, that the golden age of “ningyo joruri”was inaugurated through the talents of two men: “tayu”(chanter) Takemoto Gidayu (1651-1714) and the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon. After he opened the Takemotoza puppet theater in Osaka in 1684, Gidayu’s powerful chanting style, called “gidayu-bushi”, came to dominate “joruri”. Chikamatsu began writing historical dramas (“jidai-mono”) for Gidayu in 1685. Later he spent more than a decade writing mostly for “kabuki”, but in 1703 Chikamatsu returned to the Takemotoza, and from 1705 to the end of his life he wrote exclusively for the puppet theater. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“There has been much debate as to why Chikamatsu turned to writing for “kabuki”and then returned to “bunraku”, but this may have been the result of dissatisfaction with the relative position of the playwright and actor in “kabuki”. Famous “kabuki”actors of the day considered the play raw material to be molded to better display their own talents. In 1703, Chikamatsu pioneered a new kind of puppet play, the domestic drama (“sewa-mono”), which brought new prosperity to the Takemotoza. Only one month after a shop clerk and a courtesan committed double suicide, Chikamatsu dramatized the incident in “Sonezaki shinju”(“The Love Suicides at Sonezaki”). The conflict between social obligations (“giri”) and human feelings (“ninjo”) found in this play greatly moved audiences of the time and became a central theme for “bunraku”.

Bunraku, Kabuki and 47 Ronin

Throughout the 18th century, “bunraku”developed in both a competitive and cooperative relationship with “kabuki”. At the individual role level, “kabuki”actors imitated the distinctive movements of “bunraku”puppets and the chanting style of the “tayu”, while puppeteers adapted the stylistic flourishes of famous “kabuki”actors to their own performances. At the play level, many “bunraku”works, especially those of Chikamatsu, were adapted for “kabuki”, while lavish “kabuki”-style productions were staged as “bunraku”. Gradually eclipsed in popularity by “kabuki”, from the late 18th century “bunraku”went into commercial decline and theaters closed one by one until only the Bunrakuza was left. Since World War II, “bunraku”has had to depend on government support for its survival, although its popularity has been increasing in recent years. Under the auspices of the Bunraku Association, regular performances are held today at the National Theater in Tokyo and the National Bunraku Theater in Osaka. “Bunraku”performance tours have been enthusiastically received in cities around the world. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Domestic dramas such as Chikamatsu’s series of love-suicide plays became a favorite subject for the puppet theater. Historical dramas, however, also continued to be popular and became more sophisticated as audiences came to expect the psychological depth found in the domestic plays. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“One example of this is “Kanadehon Chushingura”, perhaps the most famous “bunraku”play. Based on the true story of the 47 “ronin”(masterless “samurai”) incident of 1701-1703, it was first staged 47 years later in 1748. After drawing his sword in Edo castle in response to insults by the Tokugawa “shogun”’s chief of protocol (Kira Yoshinaka), the feudal lord Asano Naganori was forced to commit suicide and his clan was disbanded. The 47 loyal retainers carefully plotted and carried out their revenge by killing Kira nearly two years later. Even though many years had elapsed since the incident, playwrights still changed the time, location, and character names in order to avoid offending the Tokugawa “shogun”. This popular play was soon adapted to the kabuki”stage and continues to be an important part of both repertoires.

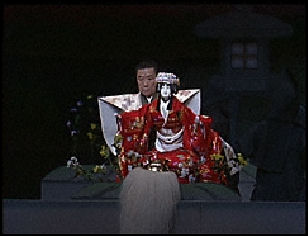

Bunraku Puppets

Bunkaru puppets are about one half to two thirds the size of human being. They appear in a raised dais near the stage with the puppeteers lurking behind them. The presence of the puppeteers is distracting until one learns to direct one’s attention at the puppets. Sometimes the puppeteers perform tasks that the puppets are supposed to do.

“Bunraku”puppets are assembled from several components: wooden head, shoulder board, trunk, arms, legs, and costume. The head has a grip with control strings to move the eyes, mouth, and eyebrows. This grip is inserted into a hole in the center of the shoulder board. Arms and legs are hung from the shoulder board with strings, and the costume fits over the shoulder board and trunk, from which a bamboo hoop is hung to form the hips. Female puppets often have immovable faces, and, since their long kimono completely cover the lower half of their bodies, most do not need to have legs. There are about 70 different puppet heads in use. Classified into various categories, such as young unmarried woman or young man of great strength, each head is usually used for a number of different characters, although they are often referred to by the name of the role in which they first appeared. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

It has been said the puppets are able convey more emotions than humans. Each puppet displays “kata” movements, typical of all human beings, and “fura” movements specific to the characters. A “mie” is a sudden pose struck in dramatic fashion, often accompanied\, off stage by strike of the clappers. Good furi requires flow while timing is critical to kata. Male puppets have bold sweeping moves while those of the females is more refined and detailed.

About 40 or 50 puppets are used in a single play. If taken care of properly a puppet can be used for 150 years. The hair for the puppets is made skilled craftsmen from human hair and yak hair. Individual strands are sewn into a copper doll mask, an arduous process that stretches out the making of a single wig to three weeks. There are 80 different hair styles for male puppets and 40 for females ones. The heads get their spring from the fins of right whales. Even though these whales are endangered enough old fins have been stockpiled to last 100 years.

Features of Bunraku Puppets

Each puppet has a generic frame. For a performance different heads and costumes are attached to create a character that weighs up to 10 kilograms. There about 50 wooden heads, or “kashira”, are available, depicting different character types ranging from tragic male heroes (“bunshichi”) to old grannies (“baba”).

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: result of a long process of evolution. Early bunraku puppets were rather simple and small in size, approximately half their present dimensions. It was in 1734, over a century after the birth of bunraku, that three puppeteers were employed to manipulate the puppets of the plays’ main characters. Soon the puppets grew to their present dimensions, while their mechanism was improved so that their fingers, mouths, and eyes could be moved. However, only some of the puppets have movable fingers or facial features. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

With their skilfully carved heads and period costuming the “actors” or puppets of bunraku are the The puppets are assembled for each production. At other times they are stored in pieces. The most dominant part of a puppet is, of course, its head (kashira). The size of the head varies according to the type of character. A powerful warlord has a bigger head than, for example, a humble villager. **

The puppets’ complexions also vary according to the character from brownish to pure white. Some heads represent stock types, such as a beautiful maiden, a young boy, a villager, a townsman etc., while some heads are reserved for particular roles. In the case of some characters, the puppet’s head is changed during the play in order to show, for example, the character’s ageing. **

The stylisation of the facial features reminds one of skilful caricatures, a characteristic that is also dominant in live actors’ facial expressions in bunraku’s sister form, kabuki. The puppet heads are attached to a rod with which the main puppeteers operate them. In the case of a puppet that has movable parts in its face, strings are added to the rod with which the movable facial features can be manipulated. **

The rod is attached to a shoulder board from which pieces of fabric hang. The puppet’s hips, in the form of a bamboo hoop, are attached to the pieces of fabric. The puppets are simply outlined by means of costuming. It replicates, in the case of plays dealing with feudal intrigues, the conventions of the Muromachi period and, in the case of plays dealing with contemporaneous events, the costumes of the Edo period. **

Puppets do not have arms. Only a string attaches the wooden hands and the forearms to the shoulder board. Both hands are connected to rods with which they are operated. Only male puppets have feet, similarly attached to the body. In the case of the female puppets, the impression of the feet movements is created by manipulating the hems of their kimonos. The puppets may handle various props, such as a sword, a fan etc. **

Bunraku Performers

The “omozukai”(principal operator) inserts his left hand through an opening in the back of the costume and holds the head grip. With his right hand he moves the puppet’s right arm. Holding a large warrior puppet can be an exercise in endurance since they weigh up to 20 kilograms. The left arm is operated by the hidarizukai”(first assistant), and the legs are operated by the “ashizukai”(second assistant), who also stamps his feet for sound effects and to punctuate the “shamisen”rhythm. For female puppets, the “ashizukai”manipulates the lower part of the “kimono”to simulate leg movement. In Chikamatsu’s day, puppets were operated by one person; the three-man puppet was not introduced until 1734. Originally this single operator was not seen on stage, but for “Sonezaki shinju”(“The Love Suicides at Sonezaki”), master puppeteer Tatsumatsu Hachirobei became the first to work in full view of the audience. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Today all three puppeteers are out on stage in full view. The operators usually wear black suits and hoods that make them symbolically invisible. A celebrity in the “bunraku”world, the principal operator often works without the black hood and in some cases even wears a brilliant white silk robe. Like the puppeteers, the “tayu”and the “shamisen”player were originally hidden from the audience but, in a new play in 1705, Takemoto Gidayu chanted in full view of the audience, and in 1715 both the “tayu”and “shamisen”player began performing on a special elevated platform at the right of the stage, where they appear today. The “tayu”has traditionally had the highest status in a “bunraku”troupe. As narrator, he creates the atmosphere of the play, and he must voice all parts, from a rough bass for men to a high falsetto for women and children. The “shamisen”player does not merely accompany the “tayu”. Since the puppeteers, “tayu”, and “shamisen”player do not watch each other during the performance, it is up to the “shamisen”player to set the pace of the play with his rhythmic strumming. In some largescale “bunraku”plays and extravaganzas adapted from “kabuki”, multiple “tayu-shamisen”pairs and “shamisen”ensembles are used.

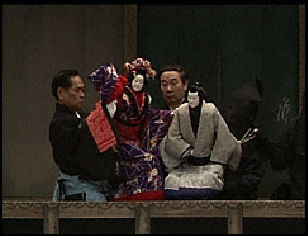

Bunraku Puppeteers

Each puppet is operated by three puppeteers: one for the legs, one for the left arm with the main puppeteer operating the body, right arm and head, including the toggle control for facial expressions. The three must be able to conduct their movements in unison. Typically the two assistants try to time their breathing with the main puppeteer to maintain coordination. Good puppeteers are able to bring drama and personality to their characters without overdoing it. The puppeteers are cloaked in black, with black head coverings over their faces, but are still visible manipulating the puppets. Only the master puppeteers show their faces. They perform wearing formal kimonos. They only appear without hoods in important scenes and maintain a Zen-like expression so as not to detract from the action.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Several puppeteers are often visible to the audience, on a wide bunraku stage. They are dressed in black robes and most of them wear black hoods, which cover their faces from the spectators. In Japanese theater, black is the colour of invisibility. For first-timers, the puppeteers dominate the stage for a while but soon the attention inevitably turns to the puppets and their surprisingly human-like actions, emotions, and even breathing. Minor characters, which have no movable fingers or facial features, are usually operated by only a single puppeteer. The more complicated puppets of the main characters are, however, usually operated by three puppeteers. This “three-man operation” is one of the specialities of bunraku and it culminates this complicated art form.[Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The coordination of these three puppeteers is of the utmost importance, as it makes it possible to create the illusion of life in the inanimated puppets. The puppeteers are divided into three ranks: the chief puppeteer (omozukai), who operates the doll’s head and right hand, the puppeteer (hidarizukai), who operates the puppet’s left hand, and the leg handler (ashizukai). It is said that ten years of training is needed before a puppeteer is able to operate the doll’s legs properly and another ten years before he is able to manipulate the left hand. Ten more years of training finally enables a manipulator to reach the rank of chief puppeteer. Of course, none of these puppeteers is a soloist. The illusion of a living puppet depends on the perfect coordination of the teamwork of these three puppeteers. **

It is said that to be a good puppeteer you need to start training by the age of 15. Puppeteers “learn through the body” and need to be flexible, especially to operate the awkward leg movements. To become a master requires 10 years of working as a leg puppeteer and then another 10 years as a left arm puppeteer. These days because of shortage of puppeteers — there are only about 40 bunraku puppeteers — the intervals between the levels is 15 and even 20 years.

Although family lineage is not a prerequisite like it often is in kabuki and Noh, puppeteers tend to belong to the Yoshida and Kirtale families, with distinctions made between masters and students. In the old days rank was expressed with different hood shapes. Today all performers wear a pointed headdress known the “kensaki” regardless of heir rank.

Bunraku Narrator

A narrator (“tayu”) chants the story and the dialogue, providing the voices of the characters to the accompaniment of a samisen player, who is regarded as an integral part of the play, not just a provider of background accompaniment, and often serves as a kind of director. One bunraku fan, who is also a baseball fan said the tayu is like a pitcher, the samisen player is like the catcher and the puppeteers are the infielders.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Although the animated puppets are, without doubt, the visual focal point of a bunraku performance, many of the Japanese spectators focus their attention on the gidayu narrator, who together with the shamisen player sits in the full formal attire of the Edo period on a low stool on a small platform on the right side of the actual stage. The vocal range of a gidayu narrator is simply amazing. While he narrates the story, he also takes the lines of the puppet characters by speaking and singing. He uses both his vocal cords and a deep abdominal voice while changing his expression from whispers to heartbreaking declamations and further on to furious shouts. The narration technique is divided into three styles. Kotoba refers to the spoken sections; ji refers to the sung sections punctuated by the shamisen, while fushi refers to the emotion-filled songs melodically accompanied by the shamisen. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Both the narrator and samisen player are in full view of the audience, sitting on one side of the stage. The samisen player usually sits in a frozen position with dour expression on his face. The narrator usually has a broad vocal range and is the most animated participant in what is, for the most part, a very formal affair. Although they have the script n front of them and can refer it, they generally have all the lines memorized.

A tayu dictates the pace of the story and adopts a whole range of different voices for different characters. The lines are chanted rather than read using a technique that takes decades to master. Good narrators are said to express emotion through their breathing and tie a special belt weighted with beans and sand around their abdomen and back to make sure they breath deeply and maintain proper posture and balance. The belt is said to make the tayu’s voice deeper and more penetrating and prevent hernias.

The puppets move to the rhythm of the tayu who sometimes chant with so much energy it seems like he might pass out. A tayu’s face often become bright red when reading particularly emotional scenes and it is not unheard of for blood to spew from the throat splatter on the script.

Mastering the art of gidayu narration takes decades of arduous work and only an experienced master is allowed to make slight changes to the narration, which is bound by centuries of tradition. For many the soul of a bunraku performance is its narrator. It is no wonder that it is usually a venerable narrator who gets the most enthusiastic applause from the audience. **

Bunraku Music and Stage

The art of gidayu narration is organically bound to its shamisen accompaniment. Just as the close co-operation of the three puppeteers creates an impression of life in the puppets, the collaboration of the narrator and the shamisen player elevates the written text to the level of an expressive drama. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Shamisen, a three-stringed instrument, played with a large bone plectrum, accentuates and punctuates the chanted narration as well as the stage action. A century after its introduction from China, the shamisen lute became the fashionable instrument of the Edo period. It was adopted not only by bunraku, but also by kabuki theater, as well as the musical forms popular in the geisha houses. Besides the shamisen accompaniment, bunraku also uses atmospheric off-stage music, known as geza, which is also heard in kabuki performances. A particular aural effect is created by wooden clappers, which announce the beginning of the play. **

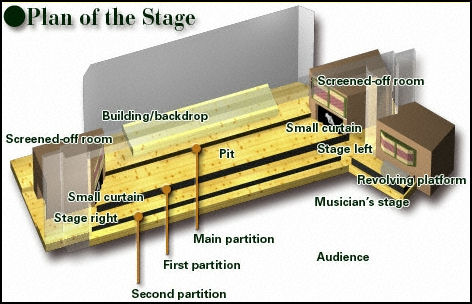

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: A bunraku stage is a rather complicated construction. Its main characteristic is its working space for the puppeteers, which is about one metre deeper than the actual stage. This enables the puppeteers to operate the puppets at the right height for the audience. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The stage structure includes several railings to which various painted backdrops and side drops may be attached. Bunraku usually uses painted scenery, which reflects the aesthetics of kabuki’s complicated stage decorations. The movable painted backdrop and side screens can be quickly changed in order to form, for example, a house with is garden and its cut-away interior, enabling the audience to see both the interior and exterior of the house. **

Special tricks may be employed. A stormy sea may be created by blue, movable waves. The impression of walking or travelling is evoked by rolling a backdrop with a landscape painting from one side to another. Illusions are created in much the same way as on the kabuki stage, although mini-sized. Side by side with the main stage, on the right side of the audience, stands a smaller stage or a platform, on which the narrators sit together with the samisen players. It has a revolving floor, which makes it possible to change the narrators and musicians in the blink of an eye according to the needs of the production. **

Bunraku Action

Like Noh, the pace of bunraku is slow and somewhat tedious and the plot is often rooted in Confucian morality and often feature characters torn between duty and love. The characters are often complex and multidimensional than characters in kabuki.

Sometimes the chanting of a single word can take four minutes. One tayu told the Daily Yomiuri, "Once you're in tune with the slower, peaceful rhythm you will enjoy the play. And of course some seemingly boring parts have been added deliberately to make the climax seem more intense."

The puppets look as if they are standings or walking on the stage but actually they are hoisted in mid-air by puppeteers standings in a submerged stage pit known as the “funazoko”. The illusion is achieved by a low wall in front of the puppets and the puppeteers that suggests the ground levels and fools almost everyone. The platform rotates at the end of each scene.

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “When I first saw a performance of puppet theater I was blown away — not by technique, which is respected greatly — but because I was able to completely forget the fact that the puppeteers were even employing any particularly special technique...When Obatsu wept because he imagined indifference of her lover. It was all about the dolls. Those men in black behind them were simply there to help make possible their theatrical art...I was filled with grief for her, and the guy lurking near her seemed a totally irrelevant bystander.”

Bunraku Plays

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Bunraku and its contemporaneous sister art form, sensational kabuki, share the same repertoire to a great extent. The plays can be divided into two categories, jidaimono or “historical plays” and sewamono or “domestic” plays, which recount the fates of ordinary people. Jidaimono is the older of these two types of play, since it had been customary for the joruri storytellers to narrate the great epics of the feudal period, such as The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari) and the Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari). This tradition was then transformed into the historical bunraku plays. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Plays that originally had six acts were later formed into five-act plays. In their structure they follow the principle of jo-ha-kyu, which is already found in noh. It refers to the play’s structure, which should consist of a beginning, a middle part, and a finale. Nowadays it is common for only one act of a full play to be staged as a bunraku production. Sewmanono, or the domestic plays, are slightly simpler in their structure. They came into being thanks to the fruitful co-operation of the celebrated playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) and the joruri narrator Takemoto Gidayu (1651–1714). Chikamatsu was born into a samurai family and was familiar with noh singing. He later specialised in writing joruri narration. He wrote plays for a famous kabuki actor of the period, but at the very beginning of the 18th century in Osaka he started his collaboration with Takemoto. **

It had been customary for bunraku plays to be kinds of collaborative works by several authors including narrators, puppet masters etc. However, now Chikamatsu focused on writing and Takemoto specialised in narration, which led to the golden age of bunraku and to the birth of sewamono plays. Sewamono indicates a play which deals with the loves, longings, and tragedies of ordinary people of the Edo period. Although the feudal period and its strict samurai ideology already belonged to the past, society was still hierarchical and ruled by rigid moral codes. **

The basic conflict between social obligation (giri) and an individual’s personal longings, passions and emotions (ninjo) became the basic theme for the sewamono plays, as has also been the case in many Indian, Chinese and Western dramas too. Chikamatsu’s plays are characterised by deep humanism and the understanding of the human condition of ordinary people. The theme of suicide became extremely popular, describing the exploits of individuals who were unable to solve the conflict of giri and ninjo otherwise than by killing themselves. **

Plays with a suicide theme were often based on cases in real life. The plays, on the other hand, inspired many people to follow their example and end their lives in suicide. This led to an official ban on these kinds of plays. One special branch of suicide plays is those that recount lovers’ double suicides (shinju). The most famous is Chikamatsu’s early play Sonezaki shinju (Double Suicide in the Garden of Sonezaki Temple), which was based on true events. In its touching, almost melodramatic pathos, the last act of the play, in which the lovers, in the darkness of the night, head for the temple garden, then make their double seppuku, is among the pearls of world drama. **

Bunraku productions generally open after only one or two full days of rehearsals. A limited number of performances and a limited amount of time between productions means time can not be wasted. It is has been said that this kind of pressure keeps performers on their toes.

Famous Bunraku Plays

The most famous bunraku plays were written in the18th century and are based on history, literature, current events and the lives or ordinary people at the time they were written. Classic puppet plays were developed by famous chanter Talemoto Gidayu (1651-1714) and the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1654-1724), who also wrote kabuki plays.

One of the most famous plays, “Kanadehon Chushingura” (1748) is a 10-hour tale with 10 acts and a prologue. Based on a real event that occurred in 1702, it is about 47 samurai who avenged the death of their lord and then committed suicide. “Sonzezaki Shinju” climaxes with a double suicide and is based on a real story.

Other well known plays include “Shinju Ten ni Amijima” (“Love Suicides at Amijima”) and “Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura” (“Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees”). The later was written in 1748 and draws on the ancient feud between Heike and Genji families with much of the action revolving around three on-the-run generals who stop at a sushi shop and are served up, among other things, the severed head of a servant killed earlier in the day.

“Imoseyama Onna Teiken” by Chikamatsu Hanji is sometimes referred to as Japan’s “Romeo and Juliet” even though the reconciliation to two feuding families through the death of a young couple is only part of a story filled deceit, bullying and jealousy. Central acts in the story are the killing of a daughter by her mother and the stabbing death of a jealous woman with a magic flute so her blood can mixed with that of a deer to break the spell protecting an evil leader who controls Japan after his father’s suicide.

“Ehon Taikoo” (1799) by Chikamatsu Yanagi is regarded as the last great bunraku work. Even though the title, which means “Chronicle of Taiko,” suggests the play is about Toyotomi Hideyoshi, known by the name Taiko, it is actually more about Akechi Mitsuhide, the general who suddenly turned against the brutal leader Oda Nobunaga and brought about his death in 1582, before falling to Hideyoshi days later. In one tragic scene Akechi (known as Takechi in the play) kills his mother with a homemade bamboo spear thinking she is a disguised Hideyoshi (Hisayoshi in the play) just before Akechi’s son shows up, mortally wounded and breathes his last breath at his father’s feet.

Sonezaki Shinju (The Love Suicides at Sonezaki)

“Sonezaki Shinju” (“The Love Suicides at Sonezaki”) is a seminal piece of traditional bunraku puppet theater. Based on a real incident from the Edo period (1603-1867), it is a tragic love story between Tokubei, a young soy sauce shop clerk, and the courtesan Ohatsu. The piece is frequently performed in Japan and is also popular overseas. A modern performance of the recently found complete script was first undertaken by master puppeteer Kiritake Kanjuro, who performed the opening sequence alone, a style that originated in the Edo period. In many modern performances the major characters are each operated by a team of three puppeteers. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 21, 2013]

This masterpiece of Chikamatsu Monzaemon was the first of the new genre of domestic drama (“sewa-mono”) plays focusing on the conflicts between human emotions and the severe restrictions and obligations of contemporary society. The great success of this play led to many more dramas on the tragic love affairs of merchants and courtesans, and it is also said to have spawned a string of copycat love suicides. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Scene 1: Making the rounds of his customers, Tokubei, clerk at a soy sauce dealer, meets his beloved, the courtesan Ohatsu, by chance at Ikutama Shrine in Osaka. Weeping, she criticizes him for neglecting to write or visit. Tokubei explains that he has had some problems, and at her urging he tells the whole story. Tokubei’s uncle, the owner of the soy sauce business, had asked him to marry his wife’s niece, but Tokubei refused because of his love for Ohatsu. However, Tokubei’s stepmother agreed to the marriage behind his back and took the large dowry with her to the country. When Tokubei again refused the marriage, his angry uncle demanded the return of the dowry money. After finally managing to get the money from his stepmother, Tokubei lent it to his good friend Kuheiji, who is late paying it back. Just then a drunken Kuheiji arrives at the shrine with a couple of friends. When Tokubei urges him to return the money, Kuheiji denies borrowing it, and he and his friends beat up Tokubei. When Kuheiji has gone, Tokubei proclaims his innocence to bystanders and hints that he will make amends by killing himself.

Scene 2: It is the evening of the same day and Ohatsu is back at Temma House, the brothel where she works. Still distraught at what has happened, she slips outside after catching a glimpse of Tokubei. They weep and he tells her that the only option left for him is suicide. Ohatsu helps Tokubei hide under the porch on which she sits, and soon Kuheiji and his friends arrive. Kuheiji continues to proclaim Tokubei’s guilt, but Ohatsu says she knows he is innocent. Then, as if talking to herself, she asks if Tokubei is resolved to die. Unseen by the others, he answers by drawing her foot across his neck. (Since female puppets do not have legs, a specially made foot is used for this scene.) Kuheiji says that if Tokubei kills himself he will take care of Ohatsu, but she rebukes him, calling him a thief and a liar. She says she is sure that Tokubei intends to die with her as she does with him. Overwhelmed by her love,Tokubei responds by touching her foot to his forehead. Once Kuheiji has left and the house is quiet, Ohatsu manages to slip out.

Scene 3: On their journey to Sonezaki Wood, Tokubei and Ohatsu speak of their love, and a lyrical passage spoken by the narrator comments on the transience of life. Hearing revelers in a roadside teahouse singing about an earlier love suicide, Tokubei wonders if he and Ohatsu will be the subject of such songs. After reaching Sonezaki Wood, Ohatsu cuts her sash and they use it to bind themselves together so they will be beautiful in death. Tokubei apologizes to his uncle, and Ohatsu to her parents, for the trouble they are causing. Chanting an invocation to Amida Buddha, he stabs her and then himself.

Bunraku Budget Cuts

The bunraku world is currently facing subsidy cuts from the Osaka prefectural and municipal governments. In 2012, Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto cut the amount of subsidies paid to bunraku by 25 percent and also announced a possible freeze on subsidies to the Bunraku Association. Although Hashimoto finally agreed to pay the money after discussions with bunraku performers, he has suggested the current lump-sum subsidy payment system be abolished in the 2012-2013 fiscal year and instead money be paid to each project to promote bunraku. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 5, 2012]

Many bunraku performers--tayu narrators, puppeteers and shamisen players--are experiencing financial hardship. Although they receive fees for their participation in more than 130 performances a year by theaters in Tokyo and Osaka, their monthly income is little more than 120,000 yen-130,000 yen, even counting the "fostering fees" they are paid by the association from subsidies and revenues earned on local tours. [Source: Takumi Harada, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 24, 2012]

Bunraku Deals with Budget Cuts

Bunraku was rocked by Hashimoto's announcement that the theater's subsidies might be frozen in 2012. Undaunted, the troupe performed the entire epic of the Kanadehon Chushingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers) in November at the National Bunraku Theater in Osaka. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 28, 2012]

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: The subsidy cut shocked bunraku performers, fans and others. The performers began making efforts to cope with the situation by increasing its public presence and popularity and also adopting an unconventional publicity approach."Bunraku is traditionally supposed to be performed as a team, so we hadn't thought of promoting individual performers this way," said Toyotake Rosetayu, 46, one of the performers. Yoshida Ichisuke, 42, who also performed in the event, said, "Bunraku performers are getting more and more enthusiastic about increasing the fan base outside bunraku theater." Toshimi Matsubara, 61, a theatrical producer who organized the event, said, "The performers' desire to do something [to overcome recent problems] has become a driving force. I want to hold regular events in the future." [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 5, 2012]

The number of visitors to the annual summer bunraku puppet theater performances at the National Bunraku Theatre in Osaka in 2012 increased by 40 percent from the previous year. The performances, held from July 21 to Aug. 7, attracted 25,508 people, the second-highest number since 1993, when the annual summer event began giving three shows a day. Following the successful summer performance, there was a sold-out bunraku event. It featured five bunraku performers in their 30s and 40s, who are regarded as young in the bunraku world. The event, titled Sakuya Hanagata Bunraku (Blooming bunraku stars), held at Osaka Club Hall in Chuo Ward, was intended to promote promising performers. The idea was modeled after similar events for kabuki. This was the first such event for bunraku.

When preparing the event, the theater staff racked their brains to make promotional leaflets for the performance more eye-catching. They usually use stage photos of several plays in the program that feature master performers. This time, however, they used photos only for Sonezaki Shinju (The Love Suicides at Sonezaki), the highlight play of the summer show. Eiji Mizuno, director of the Japan Arts Council that operates the bunraku theater, said: "We ventured to use the more appealing method. Nobody objected to it." Performers were also active in attracting visitors to the event. Twenty-one of them gave a demonstration of bunraku at JR Osaka Station and provided leaflets to passersby.

The theater's November performance staged Kanadehon Chushingura (The Treasury of the Loyal Retainers) in its entirety. It is one of the most spectacular and popular pieces in the bunraku repertoire. It was be the first performance of the piece in its entirety in Osaka in eight years. The theater hosted some events at subway stations to publicize the performance.

Life of a Bunraku Student

Takumi Harada wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Sitting up straight, Takemoto Kosumidayu, 24, opens a training textbook he borrowed from his master and starts carefully copying the words written in unique gidayu characters on his washi Japanese paper. The textbook is based on Kanadehon Chushingura, a famous and beloved story of 47 loyal samurai who avenged their master after he was forced to commit harakiri ritual suicide over a conflict with another lord. [Source: Takumi Harada, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 24, 2012]

Kosumidayu works as a tayu narrator in bunraku, a traditional performing art also known as ningyo joruri, which uses puppets, gidayu narration and shamisen music to convincingly and powerfully tell stories that reveal human nature. He lives in a six-mat studio apartment where his stage wardrobe, including hakama trousers, is hung on a curtain rail. It has been less than three years since he became a disciple of living national treasure Takemoto Sumitayu, 88, a leading tayu narrator. Kosumidayu, a native of Fukuoka, is the second-youngest among 24 tayu of the Bunraku-Kyokai association.

When he was a university student he became fascinated with and absorbed in traditional arts, such as kabuki and bunraku, and often went to see live performances. The day he first saw his current master's performance, he was mesmerized by Sumitayu's overwhelming power of expression. Although Sumitayu said at that time he was too old to take on an apprentice, Kosumidayu incessantly bowed to him and fought to quell his parents' opposition to his dream. Kosumidayu literally means "little Sumitayu.”

Kosumidayu has no pocket money after paying his rent and buying stage costumes. Until recently he was financially supported by his parents. "I spend a lot of time practicing to immerse myself in joruri narrative performance, and I have no time left for other things," Kosumidayu said. Therefore, he cannot get a job on the side. Nevertheless, he said he feels fulfilled, because he has been able to realize anew the greatness of bunraku since becoming a performer. "My own life experiences and the techniques I've honed are expressed in my performance. I have to accept this challenge, even [if it means] sacrificing my whole life." Kosumidayu has already decided to devote his entire life to bunraku.

Image Sources: 1) 4) 5) 6) Japan Arts Council; 2) 3) JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014