SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT

Kuroda Kazushige

The main duty of a samurai was to give faithful service to his feudal lord. All samurai pledged an allegiance to the emperor and fought for the shogun or their local daimyo in time of war. The concept of unquestioning loyalty is rooted in Confucianism.

Basic tenants of the strict samurai code of conduct — known as “bushido”, or the way of the samurai — included loyalty, devotion to duty, rising early, having impeccable manners, maintaining a clean and modest demeanor, having skills in practical matters such as administration, showing courage in warfare, having compassion for the oppressed, exercising justice, and possessing a willingness to die for honor and for one’s lord. Daimyo and shogun were also expected to follow the same set of values and principals.

Honor was a samurai's life. Upholding one's honor through suicide was regarded as a virtue. Loss of face was regarded as an insult that had be avenged. Surrender was an unforgivable sin that resulted in exclusion from civilized society. Dying in battle was a virtue that samurai aspired to achieve.

Websites and Sources on the Samurai Era in Japan: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Samurai Women on About.com asianhistory.about.com ; Samurai Armor, Weapons, Swords and Castles Japanese Swords Blade Diagrams ksky.ne.jp ; Making the Blades www.metmuseum.org ; Wikipedia article wikipedia.org ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp ; Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Seppuku Wikipedia article on Seppuku Wikipedia ; Tale of 47 Loyal Samurai High School Student Project eonet.ne.jp/~chushingura and Columbia University site columbia.edu/~hds2/chushinguranew : Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Samurai scholar: Karl Friday at the University of Georgia.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTO YORITOMO, GEMPEI WAR AND THE TALE OF HEIKE factsanddetails.com; KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Way of the Samurai” (Arcturus Ornate Classics) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe, inspired by film “Last Samurai” Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Samurai: An Illustrated History” by Mitsuo Kure Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop Culture” by Gavin Blair and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Samurai: A History (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “The Book of Five Rings” by Miyamoto Musashi Amazon.com; “Musashi” , a novel about the legendary swordsman by Eiji Yoshikawa. (1995) Amazon.com; “The Lone Samurai: The Life of Miyamoto Musashi” by William Scott Wilson Amazon.com; “Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth that Shatters the Bushido Mystique” by Antony Cummins Amazon.com; “Vagabond”, a popular 27-volume manga based on “Miyamoto Musashi” by the famous mangaka Takehiro Inoue Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com; “The Birth of the Samurai: The Development of a Warrior Elite in Early Japanese Society by Andrew Griffiths Amazon.com; “The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan” by Catharina Blomberg Amazon.com; Films: “Seven Samurai” Amazon.com and “Throne of Blood” Amazon.com; by Akira Kurosawa; “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise Amazon.com; ; “Twilight of a Samurai” Amazon.com; , nominated for an Academy Award in 2004

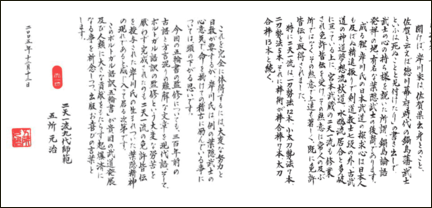

Articles of Admonition by Imagawa Ryôshun: a Guide for Samurai

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Imagawa Sadayo (1325-1420), also known as Imagawa Ryōshun, was a noted poet, literary critic, and military leader. The son of a “shugo “(military governor) of two provinces on Japan’s eastern seaboard, Ryōshun distinguished himself for his learning as well as his exploits on the battlefield. Following a series of intrigues involving the Ashikaga shogunate, Ryōshun was stripped of his military office and retired to Kyoto to write and reflect. This letter was written in 1412 by the elderly Ryōshun to his brother, Imagawa Nakaaki, who served as “shugo “of the province of Tōtōmi and who failed to live up to Ryōshun’s high standards. Ryōshun’s letter was widely admired and was used as a primer for young retainers in the Imagawa and other clans during the Muromachi and “sengoku “periods. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, the letter was used extensively as a textbook of morals (as well as fine writing) in schools for samurai as well as commoners. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Excerpts from Articles of Admonition by Imagawa Ryōshunto His Son1 Nakaaki: 1) As you do not understand the Arts of Peace, your skill in the Arts of War will not, in the end, achieve victory. 2) You like to roam about, hawking and cormorant.fishing, relishing the purposeless taking of life. 3) You have minor offenders put to death without trial. 4) But out of favoritism you pardon grave offenders. [1 Nakaaki was Ryōshun’s younger brother, but Ryōshun had adopted him. This is why Nakaaki is called ‘son.’] [Source: “The Imagawa Letter: A Muromachi Warrior’s Code of Conduct Which Became a Tokugawa Schoolbook,” by Carl Steenstrup, in “Monumenta Nipponica, “Vol. 28, No. 3 (Autumn, 1973): 299-315. 1973 Sophia University.

Satake Yoshinobu

5) You live in luxury by fleecing the people and plundering the shrines. 6) In your actions you disregard the moral law by evading your public duties and considering your private benefit first.... 8) You do not discriminate between good and bad behavior of your retainers, but reward or punish them without justice. 9) You permit yourself to forget the kindness that our lord and father showed us; thus you destroy the principles of loyalty and filial piety.”

9) You do not understand the difference in status between yourself and others; sometimes you make too much of other people, sometimes too little...12) You disregard other people’s viewpoints; you bully them and rely on force....16) Deluded by belief in your own sagacity, you scoff at others’ advice in any matter...22) A lord should scrutinize his own conduct as critically as that of his retainers.

The above articles should be kept constantly in mind. (a) Expertise in archery, horsemanship and strategy is the warrior’s routine. What first of all makes him distinguished is his capacity for management. (b) It appears clearly from the Four Books, the Five Classics, and the Military Literature that he who can only defend his territory but has no learning, cannot govern well. (c) Therefore, from childhood you should associate with upright companions, and not for a moment submit to the influence of bad friends...(p) Just as the Buddhist scriptures tell us that the Buddha incessantly strives to save mankind, in the same way you should exert your mind to the utmost in all your activities, be they civil or military, and never fall into negligence. (q) It should be regarded as dangerous if the ruler of the people in a province is deficient even in a single of the cardinal virtues of human-heartedness, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and good faith.

Way of the Samurai by Yamaga Soko

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Yamaga Sokō (1622-1685) was a Confucian philosopher and expert in military techniques and strategy. He was particularly concerned with the fate of Japan's warrior elite in an era of extended peace: after the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638, Tokugawa Japan would enjoy more than two centuries without any large-scale wars or uprisings. In his mid-sixteenth-century work “The Way of the Samurai “(“Shidō”), Sokō outlined a role for samurai in Japanese society that combined moral cultivation and civil responsibility with military preparedness. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Excerpts of “Way of the Samurai” (Shîdo) by Yamaga Sokô: “For generation after generation, men have taken their livelihood from tilling the soil, or devised and manufactured tools, or produced profit from mutual trade, so that peoples’ needs were satisfied. Thus the occupations of farmer, artisan, and merchant necessarily grew up as complementary to one another. But the samurai eats food without growing it, uses utensils without manufacturing them, and profits without buying or selling. What is the justification for this? When I reflect today on my pursuit in life, [I realize that] I was born into a family whose ancestors for generations have been warriors and whose pursuit is service at court. The samurai is one who does not cultivate, does not manufacture, and does not engage in trade, but it cannot be that he has no function at all as a samurai. He who satisfies his needs without performing any function at all would more properly be called an idler. Therefore one must devote all one’s mind to the detailed examination of one’s calling.” [Source: “Yamaga Sokō bunshū,” pp. 45.48; RT, WtdB; “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 192-194]

“The business of the samurai is to reflect on his own station in life, to give loyal service to his master if he has one, to strengthen his fidelity in associations with friends, and, with due consideration of his own position, to devote himself to duty above all. However, in his own life, he will unavoidably become involved in obligations between father and child, older and younger brother, and husband and wife. Although these are also the fundamental moral obligations of everyone in the land, the farmers, artisans, and merchants have no leisure from their occupations, and so they cannot constantly act in accordance with them and fully exemplify the Way. Because the samurai has dispensed with the business of the farmer, artisan, and merchant and confined himself to practicing this Way, if there is someone in the three classes of the common people who violates these moral principles, the samurai should punish him summarily and thus uphold the proper moral principles in the land. It would not do for the samurai to know martial and civil virtues without manifesting them. Since this is the case, outwardly he stands in physical readiness for any call to service, and inwardly he strives to fulfill the Way of the lord and subject, friend and friend, parent and child, older and younger brother, and husband and wife. Within his heart he keeps to the ways of peace, but without, he keeps his weapons ready for use. The three classes of the common people make him their teacher and respect him. By following his teachings, they are able to understand what is fundamental and what is secondary.”

Hagakure (Hidden Leaves): Guide to Bushido (Way of the Samurai)

Hagakure

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “After the unification of Japan in 1590 and the establishment of the Tokugawa Shōgunate in 1600, the samurai (warriors) remained at the top of the social scale but had fewer and fewer chances to prove their valor in battle. As opportunities to fight decreased, and samurai were employed in peacetime government positions, more attention was given to the values that defined their class. One of the most important was the loyalty samurai owed to the lord they served. In fact, the word “samurai “itself comes from a verb that means “to serve.” The lord or other high-ranking members of a clan often wrote out codes of behavior for the clan retainers. Among them, a work called “Hagakure”, or “Hidden Leaves,” has come to be seen as the one that best describes “bushidō”, “the way of the samurai.” It was written down in the early eighteenth century by a young samurai named Tashirō Tsuramoto (1678-1748), who was recording the wisdom he had learned over seven years of talks with an older, retired samurai of the Nabeshima clan named Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719). Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s ideas were expressed in conversations with his young disciple and so the resulting book is not a systematic code of rules. But some ideas are repeated often enough to be seen as essential to his thought.

The “Hagakure”(also translated as “In the Shadow of Leaves”)”“has come to be known as a foundational text of “bushidō”. Dictated between 1709 and 1716 by a retired samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719), to a young retainer, Tashirō Tsuramoto (1678-1748), “Hagakure” was less a rigorous philosophical exposition than the spirited reflections of a seasoned warrior. Although it became well known in the 1930s, when a young generation of nationalists embraced the supposed spirit of “bushidō”, “Hagakure” was not widely circulated in the Tokugawa period beyond Saga domain on the southern island of Kyushu, Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s home.” [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

According to the “Hagakure”: “”Bushido” is nothing but charging forward, without hesitation, unto death (“shinigurui”). A “bushi “in this state of mind is difficult to kill even if he is attacked by twenty or thirty people. This is what Lord Naoshige1 used to say, too. In a normal state of mind, you cannot accomplish a great task. You must become like a person crazed (“kichigai”) and throw yourself into it as if there were no turning back (“shinigurui”). Moreover, in the Way of the martial arts, as soon as discriminating thoughts (“funbetsu”) arise, you will already have fallen behind. There is no need to think of loyalty and filial piety. In” “bushidō “there is nothing but “shinigurui”. Loyalty and filial piety are already fully present on their own accord in the state of “shinigurui”. [part 1, no. 113]

Hagakure on True Bushido

Excerpts from “Hagakure” on bushido: “I have found that the Way of the samurai is death. This means that when you are compelled to choose between life and death, you must quickly choose death. There is nothing more to it than that. You just make up your mind and go forward. The idea that to die without accomplishing your purpose is undignified and meaningless, just dying like a dog, is the pretentious “bushido” of the city slickers of Kyoto and Osaka. In a situation when you have to choose between life and death, there is no way to make sure that your purpose will be accomplished. All of us prefer life over death, and you can always find more reasons for choosing what you like over what you dislike. If you fail and you survive, you are a coward. [Source: “Hagakure”, in NST, vol. 26; BS; “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 476-478; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Samurai in 1880

“This is a perilous situation to be in. If you fail and you die, people may say your death was meaningless or that you were crazy, but there will be no shame. Such is the power of the martial way. When every morning and every evening you die anew, constantly making yourself one with death, you will obtain freedom in the martial way, and you will be able to fulfill your calling throughout your life without falling into error. [part 1, nos. 2-3]

“A man of service (“hōkōnin”) is a person who thinks fervently and intently of his lord from the bottom of his heart and regards his lord as more important than anything else. This is to be a retainer of the highest type. You should be grateful to be born in a clan that has established a glorious name for many generations and for the boundless favor received from the ancestors of the clan, [and you should] just throw away your body and mind in a single.minded devotion to the service of your lord. On top of this, if you also have wisdom, arts, and skills and make yourself useful in such ways as these permit, that is even better. However, even if a humble bloke who cannot make himself useful at all, who is clumsy and unskilled at everything, is determined to cherish his lord fervently and exclusively, he can be a reliable retainer. The retainer who tries to make himself useful only in accordance with his wisdom and skills is of a lower order.”

“There is really nothing other than the thought that is right before you at this very moment. Life is just a concatenation of one thought-moment after another. If one truly realizes this, then there is nothing else to be in a hurry about, nothing else that one must seek. Living is just a matter of holding on to this thought.moment right here and now and getting on with it. But everyone seems to forget this, seeking and grasping for this and that as if there were something somewhere else but missing what is right there in front of their eyes. Actually, it takes many years of practice and experience before one becomes able to stay with this present moment without drifting away. However, if you attain that state of mind just once, even if you cannot hold onto it for very long, you will find that you have a different attitude toward life. For once you really understand that everything comes down to this one thought.moment right here and now. You will know that there are not many things you need to be concerned about. All that we know of as loyalty and integrity are present completely in this one thought-moment. [part 2, no. 17]

Hagakure on Death and Living in the Moment

scene from 47 Ronin

Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves) on Death: From the 1st Chapter The Way of the Samurai is found in death. When it comes to either/or, there is only the quick choice of death. It is not particularly difficult. Be determined and advance. To say that dying without reaching one’s aim is to die a dog’s death is the frivolous way of sophisticates. When pressed with the choice of life or death, it is not necessary to gain one’s aim. We all want to live. And in large part we make our logic according to what we like. But not having attained our aim and continuing to live is cowardice. This is a thin dangerous line. To die without gaining one’s aim "is" a dog’s death and fanaticism. But there is no shame in this. This is the substance of the Way of the Samurai. If by setting ones heart right every morning and evening, one is able to live as though his body were already dead, he gains freedom in the Way. His whole life will be without blame, and he will succeed in his calling.” [Source: “Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai,” by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, translated by William Scott Wilson (Kodansha International, 1992); Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

From the 11th Chapter: “Meditation on inevitable death should be performed daily. Every day when one’s body and mind are at peace, one should meditate upon being ripped apart by arrows, rifles, spears and swords, being carried away by surging waves, being thrown into the midst of a great fire, being struck by lightning, being shaken to death by a great earthquake, falling from thousand-foot cliffs, dying of disease or committing seppuku [ritual suicide] at the death of one’s master. And every day without fail one should consider himself as dead. There is a saying of the elders that goes, “Step from under the eaves and you’re a dead man. Leave the gate and the enemy is waiting.” This is not a matter of being careful. It is to consider oneself as dead beforehand.”

From the 2nd Chapter on living for the moment: “There is surely nothing other than the single purpose of the present moment. A man’s whole life is a succession of moment after moment. If one fully understands the present moment, there will be nothing else to do, and nothing else to pursue. Live being true to the single purpose of the moment. Everyone lets the present moment slip by, then looks for it as though he thought it were somewhere else. No one seems to notice this fact. But grasping this firmly, one must pile experience upon experience. And once one has come to this understanding he will be a different person from that point on, though he may not always bear it in mind. When one understands this settling into single-mindedness well, his affairs will thin out. Loyalty is also contained within this single-mindedness.”

Hagakure on A Good Retainer

scene from 47 Ronin

Excerpts from Hagakure on a good retainer: From the 11th Chapter: “Nakano Jin’emon constantly said, “A person who serves when treated kindly by the master is not a retainer. But one who serves when the master is being heartless and unreasonable is a retainer. You should understand this principle well.” When Hotta Kaga no kami Masamori was a page to the shōgun, he was so headstrong that the shōgun wished to test what was at the bottom of his heart. To do this, the shōgun heated a pair of tongs and placed them in the hearth. Masamori’s custom was to go to the other side of the hearth, take the tongs, and greet the master. This time, when he unsuspectingly picked up the tongs, his hands were immediately burned. As he did obeisance in his usualmanner, however, the shōgun quickly got up and took the tongs from him.” [Source: “Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai,” by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, translated by William Scott Wilson (Kodansha International, 1992); Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

From the 1st Chapter: “A man is a good retainer to the extent that he earnestly places importance in his master. This is the highest sort of retainer. If one is born into a prominent family that goes back for generations, it is sufficient to deeply consider the matter of obligation to one’s ancestors, to lay down one’s body and mind, and to earnestly esteem ones master. It is further good fortune if, more than this, one had wisdom and talent and can use them appropriately. But even a person who is good for nothing and exceedingly clumsy will be a reliable retainer if only he has the determination to think earnestly of his master. Having only wisdom and talent is the lowest tier of usefulness.”

From the 11th Chapter: “A certain general said, “For soldiers other than officers, if they would test their armor, they should test only the front. Furthermore, while ornamentation on armor is unnecessary, one should be very careful about the appearance of his helmet. It is something that accompanies his head to the enemy’s camp.”

Hagakure on Speaking and the Teachings of Yamamoto Jin’emon

Excerpts from Hagakure on speaking: From the 2nd Chapter: “At times of great trouble or disaster, one word will suffice. At times of happiness, too, one word will be enough. And when meeting or talking with others, one word will do. Oneshould think well and then speak. This is clear and firm, and one should learn it with no doubts. It is a matter of pouring forth one’s whole effort and having the correct attitude previously. This is very difficult to explain but is something that everyone should work on in his heart. If a person has not learned this in his heart, it is not likely that he will understand it. [Source: “Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai,” by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, translated by William Scott Wilson (Kodansha International, 1992); Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

From the 11th Chapter: “The essentials of speaking are in not speaking at all. If you think that you can finish something without speaking, finish it without saying a single word. If there is something that cannot be accomplished without speaking, one should speak with few words, in a way that will accord well with reason. To open ones mouth indiscriminately brings shame, and there are many times when people will turn their backs on such a person.”

From the 11th Chapter: “These are the teachings of Yamamoto Jin’emon: 1) Single-mindedness is all-powerful. 2) Tether even a roasted chicken. 3) Continue to spur a running horse. 4) A man who will criticize you openly carries no connivance. 5) A man exists for a generation, but his name lasts to the end of time. 6) Money is a thing that will be there when asked for. A good man is not so easily found. 7) Walk with a real man one hundred years and he’ll tell you at least seven lies. 8) To ask when you already know is politeness. To ask when you don’t know is the rule. 9) Wrap your intentions in needles of pine. 10) One should not open his mouth wide or yawn in front of another. Do this behind your fan or sleeve. 11) A straw hat or helmet should be worn tilted toward the front.”

Image Sources: 1) Battle reenactments JNTO; 2) armor and sword, Tokyo National Museum and samurai blogs and websites; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016