SAMURAI WARFARE

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: “Battle for the samurai was a ritual of personal and family honor. When two opposing sides confronted one another in the field, the mounted samurai would first discharge the twenty to thirty arrows at their disposal and then call out their family names in hopes of eliciting foes of similarly distinguished lineage. Two warriors would then charge one another brandishing their long swords until one was dismounted, whereupon hand-to-hand combat with short knives commenced. The loser’s head was taken as a trophy, since headgear proclaimed family and rank. To die a noble death in battle at the hands of a worthy foe brought no dishonor to one’s family, and cowardice in the face of death seems to have been as rare as it was humiliating. Frugality among these Zen-inspired warriors was as much admired as the soft living of aristocrats and merchants was scorned; and life itself was cheap, with warriors ever ready to commit ritual suicide (calledseppuku or harakiri) to preserve their honor or to register social protest. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977]

Samurai could be quite ruthless and brutal. While some saw them as well-mannered aristocrats others viewed them as thugs and organized gangsters. The samurai code is actually not all that different from the code of the yakuza, the Japanese Mafia.

Samurai pillaged and killed with the best of them. The heads of enemy officers were collected and presented to leaders as trophies and often displayed in public squares. Samurai who produced the heads of high ranking leaders were rewarded with money and promotions.

Death was valued more than defeat. Samurai were expected to kill themselves rather than surrender or be captured or be humiliated in any way. An 18th century samurai training read: “A samurai who is not prepared to die at any moment will inevitably die an unbecoming death.”

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTO YORITOMO, GEMPEI WAR AND THE TALE OF HEIKE factsanddetails.com; KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on the Samurai Era in Japan: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Samurai Women on About.com asianhistory.about.com ; Samurai Armor, Weapons, Swords and Castles Japanese Swords Blade Diagrams ksky.ne.jp ; Making the Blades www.metmuseum.org ; Wikipedia article wikipedia.org ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp ; Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Seppuku Wikipedia article on Seppuku Wikipedia ; Tale of 47 Loyal Samurai High School Student Project eonet.ne.jp/~chushingura and Columbia University site columbia.edu/~hds2/chushinguranew : Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Samurai scholar: Karl Friday at the University of Georgia.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Samurai: An Illustrated History” by Mitsuo Kure Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop Culture” by Gavin Blair and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Samurai: A History (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Way of the Samurai” (Arcturus Ornate Classics) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe, inspired by film “Last Samurai” Amazon.com; “The Book of Five Rings” by Miyamoto Musashi Amazon.com; “Musashi” , a novel about the legendary swordsman by Eiji Yoshikawa. (1995) Amazon.com; “The Lone Samurai: The Life of Miyamoto Musashi” by William Scott Wilson Amazon.com; “Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth that Shatters the Bushido Mystique” by Antony Cummins Amazon.com; “Vagabond”, a popular 27-volume manga based on “Miyamoto Musashi” by the famous mangaka Takehiro Inoue Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com; “The Birth of the Samurai: The Development of a Warrior Elite in Early Japanese Society by Andrew Griffiths Amazon.com; “The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan” by Catharina Blomberg Amazon.com; Films: “Seven Samurai” Amazon.com and “Throne of Blood” Amazon.com; by Akira Kurosawa; “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise Amazon.com; ; “Twilight of a Samurai” Amazon.com; , nominated for an Academy Award in 2004

Samurai Training

Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they were trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony.

As part of their military training, samurai were taught to sleep with their right arm underneath them so if they were attacked in the middle of the night and their the left arm was cut off the could still fight with their right arm. Samurai that tossed and turned at night were cured of the habit by having two knives placed on either side of their pillow.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed." They were expected to be proficient in the marital arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery — the traditional methods of samurai warfare — which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature. See Martial Arts, Sports

An individual didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace.

Kobudo

Kobudo, the martial arts of samurai, was a precursor of kendo, judo and other martial arts practiced today. Beginning as a mix of different combat skills, it developed through the mid-Muromachi period (1336-1573) and the Edo period (1603-1867) and branched into different schools of discipline. Of the 1,000 or so schools that existed at the end of the Edo period about 500 are still practiced in some form today.

The Imaeda school is one of the most distinguished kobudo schools of swordsmanship still practiced today. Members of this school, regarded as one of the toughest, train using real swords (not wooden staffs) and heavy armor. The philosophy taught by the school is steeped in Zen and is very esoteric and hard to understand. Swordsmen traditionally cleaned the blood off their sword after making a fatal blood, before sheathing it, with their thumb and index finger.

Imaeda school techniques include “Inchuken”, a technique for fighting in the dark, in which a swordsman moves forward with his sword half unsheathed with the point of the sheath forward to probe for one’s opponent and “nido”, in which a swordsman slices through a roll of two wet tatami mats in a single stroke. Cutting through two wet tatami mat takes about the same strength as cutting through a human torso. Another effective night fighting technique is drawing the sword out in a single motion when the sheath point touches an opponent and cutting the opponent down before he has time to react.

Each Imeada move is accompanied by a difficult-to grasp philosophical theory. “Tsuriashi” is a technique in which a swordsman raises one of his feet to move swiftly after cutting down an opponent. “Shumoko” is a move in which a swordsman overruns a mark and stumbles. Swordsman are taught to cut up from below to intimidate an opponent and not miss any vital organs.

Samurai Armor

Samurai armor was made of leather or lacquered steel plates laced together with silk cord, and sometimes adorned with lacquered wood, gilded copper, lacquered leather and gold. The main pieces were a breastplate, a similar covering for the back, and body armor for the shoulders and lower bodies. These pieces were often made of strips of deer hide and overlapping layers of small lacquered leather tiles called kozane. The primary purpose of the armor was to protect the wearer from arrows. As an early sign of Japanese technological prowess, some samurai uniforms telescoped into a special carrying case.

The armor varies a great deal from place to place and changed over time. In the beginning it was relatively unadorned. But later one, when the samurai did less fighting, it became more decorative.

The samurai helmet, with its visor and ear coverings, was the inspiration for the Darth Vader mask in the Star Wars films. A typical helmet was made with a dome of 23 strips of steel laced together with ornate silk braiding. The part that drapes of over the shoulders and back of the neck was made of layers of kozane. Samurai helmets look heavy but were often lightened with wood and were comfortable for the wearers.

The most elaborate helmets, known as “kawari kabuto” (samurai parade masks), were created for ceremonial parades to Edo not battles. They featured a mind-boggling variety of decorative motifs, inspired by things like family crests, abalone shells, fans, carp's tails, clamshells, whirlpools, bat's ears, mountains, rivers, valleys and morning glory flowers. A number were made with large rabbit ears. Rabbits were admired by samurai because their speed. Others have what look like Mickey Mouse ears. Sometimes these were worn in battles to help samurai identify who was one their side and who wasn’t.

Heavy armor offers protection but also limits movement and slows a samurai down. Samurai armor weighs near 20 kilograms and takers 40 minutes to put on. In October 2009, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened a special exhibition of Japanese weaponry ad armor called “Art of the Samurai: Japanese Arms and Armor, 1156-1868" with 214 masterpieces, including armor, sword fittings, bows and arrows, banners and equestrian equipment, with 34 deemed National Treasures and 64 deemed Important Cultural Properties. The items were collected from 62 places across Japan such as regional and national museums, temples, shrines and private collections.

On the exhibition, Washington Post art critic Blake Gopnik wrote: “The Met show has Japanese sword and dagger blades so gorgeously forged, into such pristine and subtle shapes, that they put minimalist sculpture to shame. There were helmets that were so surreal — one with soaring rabbit ears on top, another that rose up into a lifelike fist, another made to look just like a gilded sea slug — that Salvador Dali world have been proud to have created them.

In October 2009, a 17th century suit of Japanese armor fetched a record $602,500 at a Christie’s auction in New York. The armor, which made red and blue leathers plates and lacquered with gold, was purchased by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Samurai Weapons

Swords have traditionally been the preferred weapon of samurai. Samurai traditionally carried two tempered steel swords — the katana (long sword) for fighting and the wakizashi (a 12-inch dagger) for protection and suicide. Worn at the waists, these swords served as both weapons and symbols of samurai authority.

Only samurai could carry both of swords. The peasant class was forbidden from using either one. “Katanagari “ described the confiscation of swords from non-samurai in the 1600s. Court women sometimes carried small-bladed daggers to use for suicides or to avoid being raped during invasions. The swords of high-ranking samurai were decorated with elaborate engravings of dragons and other beasts.

Swords in Japan have long been symbols of power and honor and seen as works of art. Often times swordsmiths were more famous than the people who used them. Traditionally Japanese swords have had gently curved blades. Long swords of this kind were first used by soldiers who fought on horseback in the Heian period (794-1192). What gives Japanese swords their strength and flexibility is the fact that the metal is folded over many times. When a sword is forged it is heated and then hammered flat, and after the metal is flat enough its is folded over. The same process is repeated many times until literally thousands of layers of metal are fussed together.

Other samurai battle weapons included the “etsi” (giant battle ax), “geki” (two pronged spear), and bows and arrows. Some samurai foot soldiers used both long bows and short bows. Samurai cavalry were skilled at shooting arrows while riding on a galloping horse. Some of them wore iron stirrups that were designed to smash the faces of enemy foot soldiers. For a while, mostly in the late 16th century, samurai also used muskets and cannons. Samurai didn’t eschew firearms on the basis of honor or anything like that; they were prevented from using them by the shogun.

Okanehira is regarded as the greatest of all Japanese swords. Modern metallurgist have only recently worked out the secret behind traditional samurai swords. Their unrivaled strength and sharpness was achieved by regulating the amount of carbon in the steel and the temperature during forging and cooling.

See Swords, Crafts, Culture and Art

Samurai Swords

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: The symbols of the Zen samurai were the sword and the bow. The sword in particular was identified with the noblest impulses of the individual, a role strengthened by its historic place as one of the emblems of the divinity of the emperor, reaching back into pre-Buddhist centuries. A samurai’s sword was believed to possess a spirit of its own, and when he experienced disappointment in battle he might go to a shrine to pray for the spirit’s return. Not surprisingly, the swordsmith was an almost priestly figure who, after ritual purification, went about his task clad in white robes. The ritual surrounding swordmaking had a practical as well as a spiritual purpose; it enabled the early Japanese to preserve the highly complex formulas required to forge special steel. Their formulas were carefully guarded, and justifiably so: not until the past century did the West produce comparable metal. Indeed, the metal in medieval Japanese swords has been favorably compared with the finest modern armorplate. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977 ]

“The secret of these early swords lay in the ingenious method developed for producing a metal both hard and brittle enough to hold its edge and yet sufficiently soft and pliable not to snap under stress. The procedure consisted of hammering together a laminated sandwich of steels of varying hardness, heating it, and then folding it over again and again until it consisted of many thousands of layers. If a truly first-rate sword was required, the interior core was made of a sandwich of soft metals, and the outer shell fashioned from varying grades of harder steel. The blade was then heated repeatedly and plunged into water to toughen the skin. Finally, all portions save the cutting edge were coated with clay and the blade heated to a very precise temperature, whereupon it was again plunged into water of a special temperature for just long enough to freeze the edge but not the interior core, which was then allowed to cool slowly and maintain its flexibility. The precise temperatures of blade and water were closely guarded secrets, and at least one visitor to a master swordsmith’s works who sneaked a finger into the water to discover its temperature found his hand suddenly chopped off in an early test of the sword.

“The result of these techniques was a sword whose razor-sharp edge could repeatedly cut through armor without dulling, but whose interior was soft enough that it rarely broke. The sword of the samurai was the equivalent of a two-handed straight razor, allowing an experienced warrior to carve a man into slices with consummate ease. Little wonder the Chinese and other Asians were willing to pay extravagant prices in later years for these exquisite instruments of death. Little wonder, too, that the samuraiworshiped his sidearm to the point where he would rather lose his life than his sword.”

national treasure sword

Zen Approach to Samurai Swordsmanship

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: Yet a sword alone did not a samurai make. A classic Zen anecdote may serve to illustrate the Zen approach to swordsmanship. It is told that a young man journeyed to visit a famous Zen swordmaster and asked to be taken as a pupil, indicating a desire to work hard and thereby reduce the time needed for training. Toward the end of his interview he asked about the length of time which might be required, and the master replied that it would probably be at least ten years. Dismayed, the young novice offered to work diligently night and day and inquired how this extra effort might affect the time required. “In that case,” the master replied, “it will require thirty years.” With a sense of increasing alarm, the young man then offered to devote all his energies and every single moment to studying the sword. “Then it will take seventy years,” replied the master. The young man was speechless, but finally agreed to give his life over to the master. For the first three years, he never saw a sword but was put to work hulling rice and practicing Zen meditation. Then one day the master crept up behind his pupil and gave him a solid whack with a wooden sword. Thereafter he would be attacked daily by the master whenever his back was turned. As a result, his senses gradually sharpened until he was on guard every moment, ready to dodge instinctively. When the master saw that his student’s body was alert to everything around it and oblivious of all irrelevant thoughts and desires, training began. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977 ]

“Instinctive action is the key to Zen swordsmanship. The Zen fighter does not logically think out his moves; his body acts without recourse to logical planning. This gives him a precious advantage over an opponent who must think through his actions and then translate this logical plan into the movement of arm and sword. The same principles that govern the Zen approach to understanding inner reality through transcending the analytical faculties are used by the swordsman to circumvent the time-consuming process of thinking through every move. To this technique Zen swordsmen add another vital element, the complete identification of the warrior with his weapon. The sense of duality between man and steel is erased by Zen training, leaving a single fighting instrument. The samurai never has a sense that his arm, part of himself, is holding a sword, which is a separate entity. Rather, sword, arm, body, and mind become one.

As explained by the Zen scholar D. T. Suzuki: “When the sword is in the hands of a technician-swordsman skilled in its use, it is no more than an instrument with no mind of its own. What it does is done mechanically, and there is no [nonintellection] discernible in it. But when the sword is held by the swordsman whose spiritual attainment is such that he holds it as though not holding it, it is identified with the man himself, it acquires a soul, it moves with all the subtleties which have been imbedded in him as a swordsman. The man emptied of all thoughts, all emotions originating from fear, all sense of insecurity, all desire to win, is not conscious of using the sword; both man and sword turn into instruments in the hands, as it were, of the unconscious.”

“Zen training also renders the warrior free from troubling frailties of the mind, such as fear and rash ambition—qualities lethal in mortal combat. He is focused entirely on his opponent’s openings, and when an opportunity to strike presents itself, he requires no deliberation: his sword and body act automatically. The discipline of meditation and the mind-dissolving paradoxes of the koan become instruments to forge a fearless, automatic, mindless instrument of steel-tipped death.”

Zen Approach to Samurai Archery

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: The methods developed by Zen masters for teaching archery differ significantly from those used for the sword. Whereas swordsmanship demands that man and weapon merge with no acknowledgment of one’s opponent until the critical moment, archery requires the man to become detached from his weapon and to concentrate entirely upon the target. Proper technique is learned, of course, but the ultimate aim is to forget technique, forget the bow, forget the draw, and give one’s concentration entirely to the target. Yet here too there is a difference between Zen archery and Western techniques: the Zen archer gives no direct thought to hitting the target. He does not strain for accuracy, but rather lets accuracy come as a result of intuitively applying perfect form. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977 ]

“Before attempting to unravel this seeming paradox, the equipment of the Japanese archer should be examined. The Japanese bow differs from the Western bow in having the hand grip approximately one-third of the distance from the bottom, rather than in the middle. This permits a standing archer (or a kneeling one, for that matter) to make use of a bow longer than he is tall (almost eight feet, in fact), since the upper part may extend well above his head. The bottom half of the bow is scaled to human proportions, while the upper tip extends far over the head in a sweeping arch. It is thus a combination of the conventional bow and the English longbow, requiring a draw well behind the ear. This bow is unique to Japan, and in its engineering principles it surpasses anything seen in the West until comparatively recent times. It is a laminated composite of supple bamboo and the brittle wood of the wax tree. The heart of the bow is made up of three squares of bamboo sandwiched between two half-moon sections of bamboo which comprise the belly (that side facing the inside of the curve) and the back (the side away from the archer). Filling out the edges of the sandwich are two strips of wax-tree wood. The elimination of the deadwood center of the bow, which is replaced by the three strips of bamboo and two of waxwood, produces a composite at once powerful and light. The arrows too are of bamboo, an almost perfect material for the purpose, and they differ from Western arrows only in being lighter and longer. Finally, the Japanese bowstring is loosed with the thumb rather than the fingers, again a departure from Western practice.

“If the equipment differs from that of the West, the technique, which verges on ritual, differs far more. The first Zen archery lesson is proper breath control, which requires techniques learned from meditation. Proper breathing conditions the mind in archery as it does in zazen and is essential in developing a quiet mind, a restful spirit, and full concentration. Controlled breathing also constantly reminds the archer that his is a religious activity, a ritual related to his spiritual character as much as to the more prosaic concern of hitting the target. Breathing is equally essential in drawing the bow, for the arrow is held out away from the body, calling on muscles much less developed than those required by the Western draw. A breath is taken with every separate movement of the draw, and gradually a rhythm settles in which gives the archer’s movements a fluid grace and the ritual cadence of a dance.

“Only after the ritual mastery of the powerful bow has been realized does the archer turn his attention to loosing the arrows (not, it should be noted, to hitting the target). The same use of breathing applies, the goal being for the release of the arrow to come out of spontaneous intuition, like the swordsman’s attack. The release of the arrow should dissolve a kind of spiritual tension, like the resolution of a koan, and it must seem to occur of itself, without deliberation, almost as though it were independent of the hand. This is possible because the archer’s mind is totally unaware of his actions; it is focused, indeed riveted in concentration, on the target. This is not done through aiming, although the archer does aim—intuitively. Rather, the archer’s spirit must be burned into the target, be at one with it, so that the arrow is guided by the mind and the shot of the bow becomes merely an intervening, inconsequential necessity. All physical actions—the stance, the breathing, the draw, the release—are as natural and require as little conscious thought as a heartbeat; the arrow is guided by the intense concentration of the mind on its goal. Thus it was that the martial arts of Japan were the first to benefit from Zen precepts, a fact as ironic as it is astounding. Yet meditation and combat are akin in that both require rigorous self-discipline and the denial of the mind’s overt functions.”

Early Samurai Warfare

In the early samurai era, battles were highly ritualized affairs with elaborate formalities that would not have seemed out of place in a Shakespearean drama. Before they fought samurai were required to introduce themselves by name, list their achievement, and then fire a whistling arrow. In a famous medieval war epic one samurai goes: “Ho, I am Kajiwara Heizo Kagetoki, descended from the fifth generation from Gingoro Kagemas of Kamakura, renowned warrior of the East Country and match for any thousand men. At the age sixteen...receiving an arrow in my left eye through the helmet, I plucked it forth and with it shot down the marksmen who sent it.”

The battles themselves consisted one-on-one duels that combined of wrestling, swordplay, and arrow shooting. The fighting was often carried out only by the strongest samurai, who shouted insults and as they fought. Large battles often included barrages of arrows fired by samurai on horseback and fights with swords and lances by foot soldiers. The fighting often ended abruptly when a general was killed. Casualties were usually relatively low.

Impact of the Mongol Invasions on Japanese Warfare

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: The Japanese had, however, learned a sobering lesson about their military preparedness. In the century of internal peace between the Gempei War and the Mongol landing, Japanese fighting men had let their skills atrophy. Not only were their formalized ideas about honorable hand-to-hand combat totally inappropriate to the tight formations and powerful crossbows of the Asian armies (a samurai would ride out, announce his lineage, and immediately be cut down by a volley of Mongol arrows), the Japanese warriors had lost much of their moral fiber. To correct both these faults the Zen monks who served as advisers to the Hojo insisted that military training, particularly archery and swordsmanship, be formalized, using the techniques of Zen discipline. A system of training was hastily begun in which the samurai were conditioned psychologically as well as physically for battle. It proved so successful that it became a permanent part of Japanese martial tactics. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977 ] “The Zen training was urgent, for all of Japan knew that the Mongols would be back in strength. One of the Mongols’ major weapons had been the fear they inspired in those they approached, but fear of death is the last concern of a samurai whose mind has been disciplined by Zen exercises. Thus the Mongols were robbed of their most potent offensive weapon, a point driven home when a group of Mongol envoys appearing after the first invasion to proffer terms were summarily beheaded.

battle reenactment

Later Samurai Warfare

As time went on, armies grew larger and chivalrous behavior took a backseat to winning. The Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281 were wake up calls that ritualized warfare had its limits and the future was in massed fighting and superior tactics. Battles before the Edo Period often embraced tens of thousands of samurai, supported by farmers enlisted as foot soldiers. They armies employed mass attacks with long spears. Victories were often determined by castle sieges.

Many important battles were fought in the mountains, difficult terrain suited for foot soldiers, not open plains where, horses and cavalries could be used to their best advantage. Fierce hand to hand battles with armor-clad Mongols showed the limitations of bows and arrows and elevated the sword and the lance as the preferred killing weapons Speed and surprise were important. Often the first group to attack the other’s encampment won.

Warfare changed when guns were introduced. "Cowardly" firearms reduced the necessity of being the strongest man. Battles became bloodier and more decisive. Not long after guns were banned warfare itself ended.

Upon witnessing a European drill, a high ranking samurai in 1841 ridiculed them for "rasing and manipulating their weapons all at the same time...looking as if they were playing some children's game."

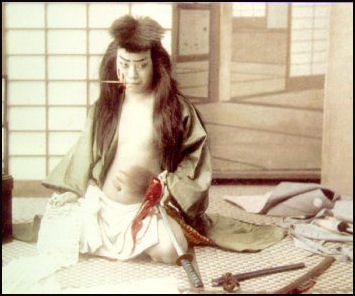

Seppuku

“Seppuku” (hari kari) is a form of ritual suicide. A samurai that for any reason dishonored himself or his lord was required to commit “seppuku” by thrusting the knife into his stomach, twisting it and making a slash across the stomach. While he did this an attendant or another samurai loped of his head with a sword.

film scene with an actor preparing for seppuku ”Junshi” (literally “following one’s lord”) described the killing ritual in which the stomach was cut from left to right, with an excruciatingly painful crosswise stroke, followed by the swordsman impaling oneself on one’s sword. Many who did this read death poems as they killed themselves. The practice was outlawed by the forth Tokugawa shogun in 1663 because too many samurai were being lost. Twenty six retainers of daimyo Nabeshima Katsushige followed him to death in 1657.

Corrupt, scheming and cowardly samurai were often featured in Japanese theater. “Ronin” were masterless samurai who refused to commit ritual suicide or dishonored themselves in some other way and wandered the countryside like homeless people.

In 1868. Japanese soldiers at Sakai near Osaka killed 11 French sailors. Twenty of the attackers were supposed to commit seppuku as punishment. The French found the spectacle so horrific to watch the ritual was stopped at the 11th one. The nine survivors demanded to die.

In 1912, General Maresukae Nogi famously marked the death of Emperor Meiji by committing seppaku. His wife, apparently willingly, plunged a dagger into her heart. In 1877 Nogi had asked the Emperor for permission to commit seppaku following his regiment’s defeat in the Satsuma Rebellion and the loss of the Emperor’s banner to the enemy. He was crushed when his request was turned down, expressing his feelings a poem that went: “My self is nothing but a person scared of death.” He made the request for seppaku again in 1905 after losing two sons in the war and again was turned down. The state propaganda machine seized upon his successful suicide as the ultimate act of self-sacrifice for the emperor and was used for propaganda purposes to aid the rise of the military. A number of writers wrote about the event.

Book: “Suicidal Honor” by Doris G. Bargen (University of Hawaii Press, 2004)

Image Sources: 1) Battle reenactmenst JNTO 2) armor and sword, Tokyo National Museume and samurai blogs and websites; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016